Mirza coquereli (A. Grandidier, 1867)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6639118 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6639238 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/253C87A7-FFE2-DB5F-FF0D-F83DACBDFDAA |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Mirza coquereli |

| status |

|

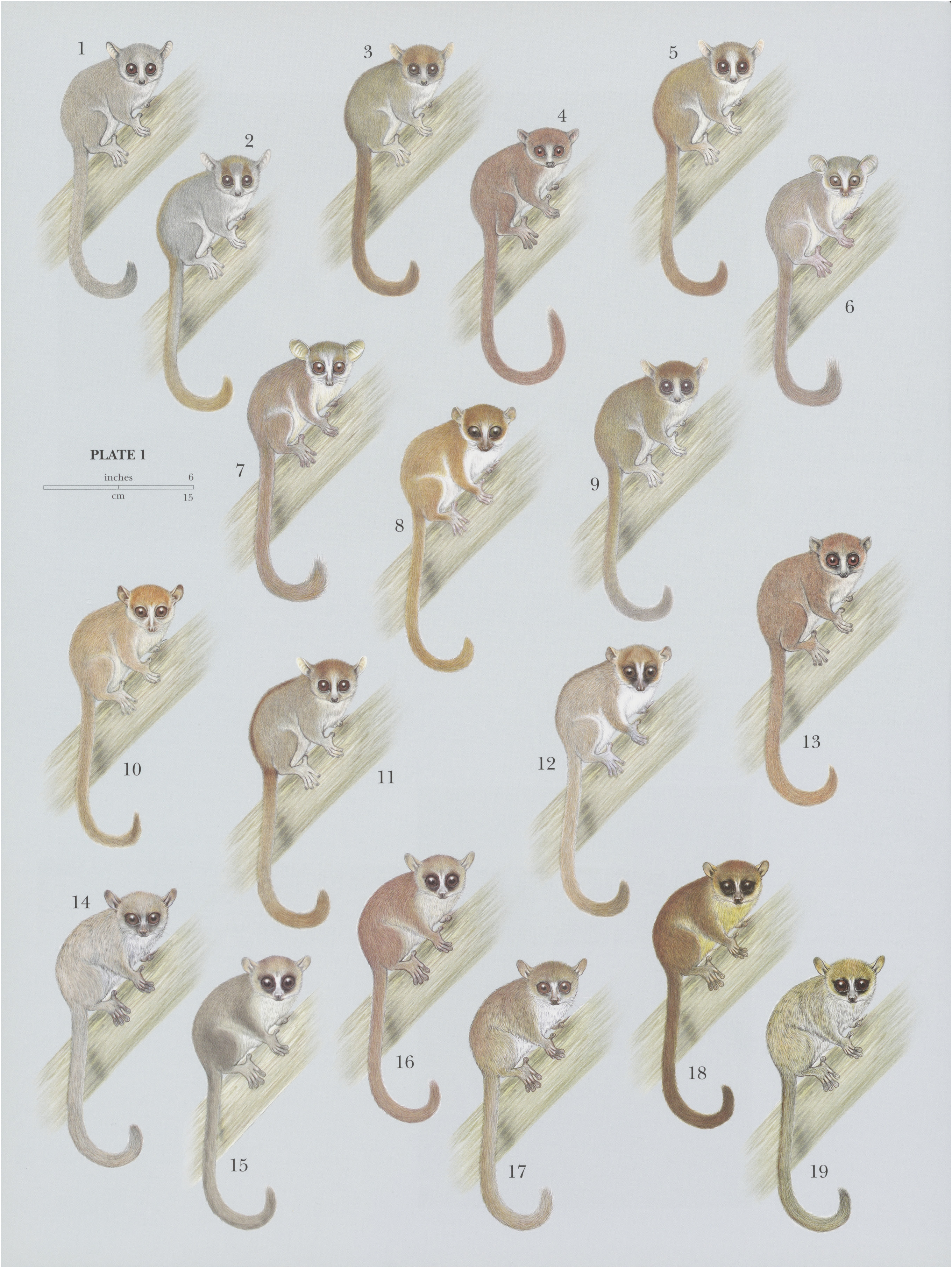

20. View Plate 1: Cheirogaleidae

Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur

French: Microcébe de Coquerel / German: Coquerel-Riesenmausmaki / Spanish: Lémur ratén gigante de Coquerel

Other common names: Giant Mouse Lemur, Southern Giant Mouse Lemur

Taxonomy. Cheirogaleus coquereli A. Grandidier, 1867 ,

Madagascar, Morondava.

This species is monotypic.

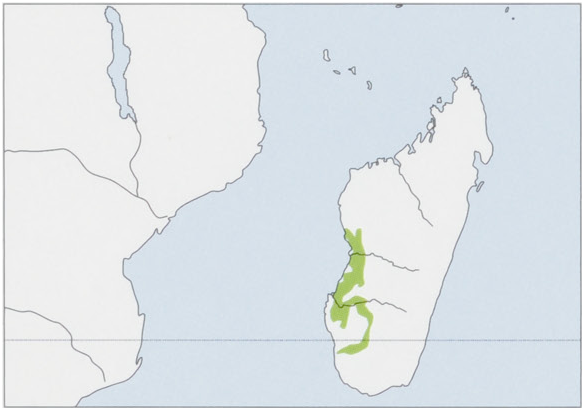

Distribution. W & SW Madagascar in the SW between the Onilahy River in the S and the Tsiribihina River in the N, including Zombitse-Vohibasia and Isalo national parks, to the N of the Tsiribihina River; possibly also Andranomena Special Reserve and Tsingy de Bemaraha and Tsingy de Namoroka national parks. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 25 cm,tail 31-32 cm; weight 317 g (males) and 299 g (females). The dorsal coat of Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemuris a rich brown or graybrown, although rose or yellow shades are often present. Ventrally, the gray hair base is visible beneath rusty or yellow tips. The tail is longer than the body, darker toward the tip, and thin but long-haired, giving it a slightly bushy appearance. Ears are large, naked, and oval-shaped.

Habitat. [Lowland dry deciduous forest fragments with dense underbrush, gallery forest, and coffee plantations. The elevational range of Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur is sea level to 700 m. Forests near water (e.g. semi-permanent ponds) with canopy heights of up to 20 m are preferred.

Food and Feeding. Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur is omnivorous, feeding on fruits, flowers, buds, gums (7erminalia, Combretaceae , and Adansonia sp. , Malvaceae ), nectar of fangoky ( Delonix bowviniana, Fabaceae ), nuts, bird eggs, and a wide variety of animal matter including insects, spiders, frogs, chameleons, small birds, and rodents. An important food source during the dry season (June-July) is the sweet-tasting larval excretions of cochineal and hemipteran insect larvae.

Breeding. The female reproductive cycle of Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur averages about 22 days. Reproductive activity in the Kirindy Forest begins in October-November, with estrus signaled by a swelling and reddening of the female’s genitals. As the female approaches sexual receptivity, males begin to follow her closely, occasionally performing a sniffing behavior. Social grooming of the female by the male takes place during estrus. A copulation plug forms in the female’s vagina after mating. Gestation is 86-89 days. Normally two infants (occasionally one and rarely three or four) are born each year. Infants are able to leave the nest at about three weeks. The mother carries them in her mouth for the first several weeks and parks them in vegetation when she forages. After three months, the young forage alone but maintain vocal contact with their mother. Females are sexually mature at one year. An individual reportedly lived for 15 years and five months in the London Zoo.

Activity patterns. Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur is nocturnal and arboreal. Individuals normally leave the nest around dusk, at which time they begin feeding or selfgrooming, or continue resting. On cold nights, they leave the nest later in the evening and return to it earlier in the morning. Travel and foraging usually occur at canopy heights of 5-10 m, although these animals do go to the forest floor occasionally. During the latter half of the night, they are more likely to be involved in social activities. While they frequently return to the nest for the second half of the night during the cooler winter, they remain active year-round and do not enter torpor.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Ecological and behavioral studies of Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur have been conducted in the Beroboka, Kirindy, and Marosalaza forests just north of Morondava. Home ranges of 1-4 ha overlap extensively, and all individuals seem to make heavy use of smaller core areas, which they defend aggressively. Male home ranges tend to overlap those of several females and other males. In the Kirindy Forest, male home ranges more than quadruple during the mating season. Males interact positively (i.e. social grooming, contact calling) with females when they make contact, and pairs travel together for short periods even during the dry season. Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur is typically solitary when foraging, and it does not nest communally. It spends its daytime hours in a spherical nest of up to 50 cm in diameter, usually placed 2-10 m high in the fork of a large branch or among dense lianas (to discourage predators). Nests are constructed of interlaced lianas, branches, leaves, and twigs chewed off from nearby trees. Only females and their offspring share nests. Each adult uses as many as 10-12 nests (although usually onehalf of them are in disrepair) and changesits sleeping site every few days. Densities reported from Marosalaza are 30-50 ind/km?, but they can also be as high as 210 ind/ km? in forests along rivers. A density of 100 ind/km?® has been recorded in the forests of Tsimembo, while 120 ind/km?® occur in Kirindy Forest. The latter population underwent an inexplicable decline after remaining steady for several years.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Near Threatened on The IUCN Red List. However, at the IUCN/SSC Lemur Red-Listing Workshop held in July 2012, Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur was assessed as Endangered due to an ongoing and predicted population decline of more than 50% over 10 years. Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur is somewhat threatened by loss of habitat and is occasionally hunted for food by locals. Nevertheless, it appears to be adaptable because it can survive in secondary forest and occurs in fairly high densities in some parts of its distribution. It occurs in Tsingy de Bemaraha and Zombitse-Vohibasia national parks and Andranomena Special Reserve. It also occurs in the Kirindy Forest (part of the Menabe-Antimena Protected Area) and Ampataka Classified Forest.

Bibliography. Ausilio & Raveloarinoro (1993), Ganzhorn (1994), Goodman (2003), Goodman et al. (1997), Groves (2001), Hawkins (1999), Hladik (1979), Hladik et al. (1980), Izard (1986), Kappeler (1997, 2003), Kappeler et al. (2005), Markolf, Roos & Kappeler (2008), Mittermeier, Louis et al. (2010), Mittermeier, Tattersall et al. (1994), Pages (1978, 1980, 1983), Petter, Albignac & Rumpler (1977), Petter, Schilling & Pariente (1971), Petter-Rousseaux (1980), Rasoloarison et al. (1995), Sarikaya & Kappeler (1997), Stanger et al. (1995).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.