Mirza zaza, Kappeler & Roos, 2005

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6639118 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6639244 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/253C87A7-FFE1-DB5F-FFD6-FD96A1B0FDAB |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Mirza zaza |

| status |

|

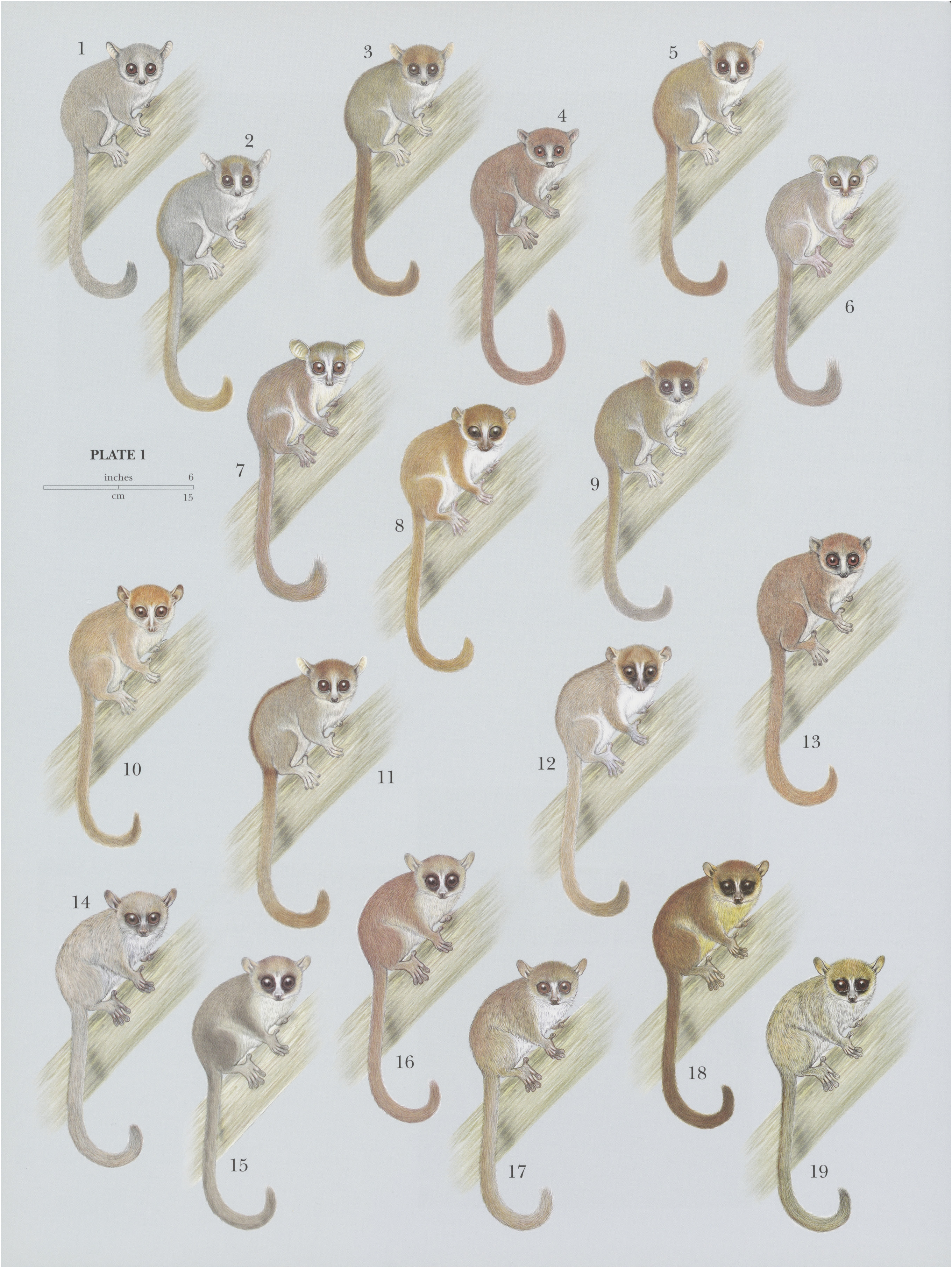

21. View Plate 2: Cheirogaleidae

Northern Giant Mouse Lemur

French: Microcebe zaza / German: Nordlicher Riesenmausmaki / Spanish: Lémur raton gigante septentrional

Taxonomy. Mirza zaza Kappeler & Roos View in CoL in Kappeler et al., 2005,

Madagascar, province of Ansiranana, Bay of Passandava, Congoni (13° 40’ S, 48° 15’ E).

This species is monotypic.

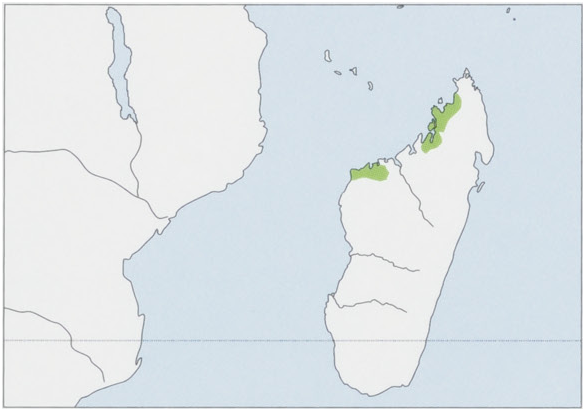

Distribution. NW Madagascar from the Ampasindava Peninsula between the Mahavavy Nord and Maevarano rivers. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body ¢.27 cm, tail 27-28 cm; weight 290 g. The Northern Giant Mouse Lemuris slightly smaller than Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur (M. coquereli ), with relatively shorter rounded ears and a shorter tail. The body is covered by short, grayish-brown fur that turns distinctly more grayish ventrally. The tail is long, bushy, and darker toward the tip.

Habitat. [Lowland dry deciduous forest fragments with dense underbrush, transitional subhumid forest, gallery forest, and abandoned cashew ( Anacardium , Anacardiaceae , an introduced species) orchards. The Northern Giant Mouse Lemur also has been observed in old banana plantations.

Food and Feeding. The Northern Giant Mouse Lemur is omnivorous and presumably has a diet similar to Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur (i.e. fruits, flowers, buds, gums, insect excretions, and animal prey such as insects, spiders, frogs, chameleons, and small birds). Cashew fruits are an important food source in some locations during the dry season in June-July.

Breeding. Based on studies of individuals from the Ambanja region, reproductive activity of the Northern Giant Mouse Lemur begins in July-August (i.e. several months earlier than when Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur begins to mate in the Kirindy Forest of the south-west). The Northern Giant Mouse Lemur is reported to be more promiscuous than Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur . Normally twins are born, occasionally triplets, and the interbirth interval is about a year.

Activity patterns. The Northern Giant Mouse Lemur is nocturnal and arboreal. It spends the first half of the night engaged in solitary activities such as feeding and the last half devoted to social activities, vocalizations, and encounters with conspecifics, which could include mutual resting, social grooming, and play. During estrus, social behaviors dominate the first half of the night.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Northern Giant Mouse Lemurs are typically solitary when active, choosing to forage alone. They spend the daytime hours in a spherical nest of up to 50 cm in diameter, constructed of interlaced lianas, branches, leaves, and twigs chewed off nearby trees. Nests are well-covered by the forest canopy, even during the dry season, and are located near the tree trunk a few meters below the tree top. Nestsites in the Ankarafa Forest are characterized by large and tall trees with many lianas. In contrast to Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur that is not known to share nests, the Northern Giant Mouse Lemur forms sleeping groups. In a study conducted in the Ankarafa Forest on the Sahamalaza Peninsula, up to four animals, including several males with fully developed testes, shared one to three group-exclusive nests during 50 days of observations. Adult males sharing nests were either unrelated or closely related (full-siblings). Nest groups remained stable for the duration of the study. The Northern Giant Mouse Lemur may show more social tendencies than is typical of Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur (perhaps associated with higher recorded densities), and it is more vocal. Group home ranges of Northern Giant Mouse Lemurs were 0-52-2-3 ha in one study, but it is not clear if this reflects natural ranging behavior or restricted ranging opportunities due to low habitat availability in a fragmented landscape. Both species of Mirza are usually observed at heights of 5-10 m, but they use all vertical strata and the ground. The Northern Giant Mouse Lemur seems to favor large trees in dense microhabitats. Morphological and behavioral data of the Northern Giant Mouse Lemur suggest a highly promiscuous mating system. Relative to its bodysize,it has the highest testicular volume recorded in any primate. High density estimates of 385 ind/km? and 1086 ind/km* have been reported from the Ambato region—several times higher than those obtained for Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur in the Kirindy Forest. Concentration of individuals in more isolated forest fragments and the presence of mango ( Mangifera , Anacardiaceae ), cashews, and other similar introduced trees in the Ambato region may help explain higher densities. Encounter rates of the Northern Giant Mouse Lemur in the Ankarafa Forest on the Sahamalaza Peninsula were comparable to those of Coquerel’s Giant Mouse Lemur in Kirindy Forest.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. The Northern Giant Mouse Lemur occurs in less than 2000 km?. Severalsites within its distribution are unoccupied, and the remaining habitat is extremely fragmented and vanishing quickly. The smallest fragments cannot support a viable population. At the IUCN/SSC Lemur Red-Listing Workshop held in July 2012, the Northern Giant Mouse Lemur was assessed as endangered due to an ongoing and predicted population decline of more than 50% over 10 years. It is currently known to occur in only Sahamalaza-Iles Radama National Park, but it may also be present in the foothills of the Manongarivo Special Reserve and a few classified forests in its known distribution (Antafondro, Andranomatavy, Anjanazanombandrany, and Antsakay-Kalobenono).

Bibliography. Andrianarivo (1981), Fleagle (1999), Harcourt & Thornback (1990), Kappeler (1997, 2003), Kappeler et al. (2005), Markolf, Kappeler & Rasoloarison (2008), Mittermeier et al. (2010), Pages (1978, 1980), Randrianambinina, Rasoloharijaona et al. (2003), Randriatahina & Rabarivola (2004), Rode et al. (2010).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.