Crellidae, Dendy, 1922

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3917.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D8CB263D-645B-46CE-B797-461B6A86A98A |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6108607 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/2125D91F-1B05-295C-7ED9-C0A1F64DFD91 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Crellidae, Dendy, 1922 |

| status |

|

Family Crellidae, Dendy, 1922 View in CoL

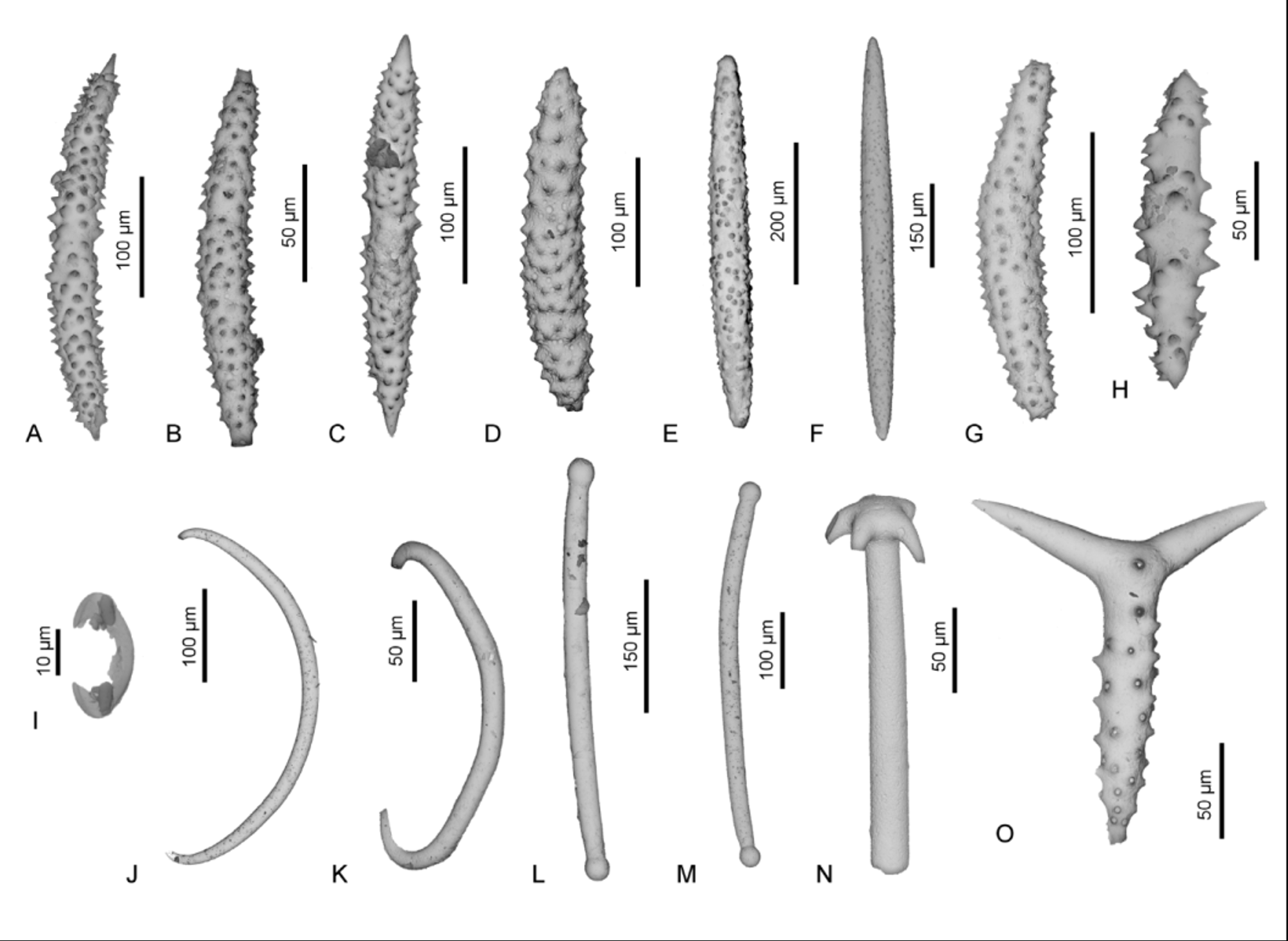

Moderately frequent, spined rhabds, called sanidasters or acanthorhabds occur in the studied samples ( Figs. 23 View FIGURE 23 A–C). These spicules vary in size from about 250 to 500 µm. There is no exact equivalent of these acanthorhabds among the known present-day sponges but they most closely resemble those of Recent Rhabdeurypon spinosum Vacelet 1969 (family Raspailiidae ; compare with Fig. 22 View FIGURE 22 B), as well as the spicules of Crellastrina alecto Topsent, 1898 [described as Yvesia ; family Crellidae (see Fig. 22 View FIGURE 22 D)]. The comparison of the studied fossil acanthorhabds with those of Rhabdeurypon revealed that the Recent ones are less regular; the spines are not so regularly arranged along the spicule shaft (in the studied spicules the size of spines increases in the centre of a rhabd). Furthermore, the spicules of Rhabdeurypon are smaller than the fossil ones, being only slightly larger than 100 Μm.

On the other hand, comparison of the studied Eocene spicules with those of Crellastrina alecto shows that the crellid curved ectosomal acanthorhabds are covered with long conical spines or tubercles, often partly finely spined or rugose (see Fig. 22 View FIGURE 22 D), whereas the studied spicules possess conical spines arranged more regularly. However, if carefully examined, despite the fact that the studied spicules do not have mucronate spine tips, they have sparse spines arranged along the whole spines (see Fig. 23 View FIGURE 23 D). The size of the studied strongylostyles and crellid spicules is similar (about 540 µm). In my opinion, spicules studied here resemble those of C. alecto the most. It is supported by the fact that they are smaller (than those of Rhabdeuryphon) and have also some kind of sculptured spinose surface. Unfortunately, none of the discussed Recent species currently live around Australia; C. alecto inhabits waters around the Azores (van Soest 2002b) and R. spinosum is known so far only in the Mediterranean ( Vacelet 1969). Keeping in mind that some other spicules examined here were assigned to sponges inhabiting the Azores, this assignment also seems possible.

There are also other types of acanthorhabds in the Eocene samples that differ from those described above by having more twisted axes ( Figs. 23 View FIGURE 23 E–I) and/or more regularly arranged spines ( Figs. 23 View FIGURE 23 J–L). One cannot be sure if this is only an effect of intraspecific variability or if they belong to a different taxon. It seems that spicules described here belong to extinct sponge species that do not have Recent equivalent but they still resemble those of Crellastrina the most.

The fossil record of these spicule morphotypes is very sparse. Some of the studied morphological types have been described previously from the deposits of the same age and area (see Hinde 1910, pl. 1, figs. 12, 13), as well as from the Oligocene sediments from around Tasmania ( Kennet et al. 1975, pl. 1, figs. 10–12).

Other not precisely assigned spicules of the order Poecilosclerida . Beside the spicules of poecilosclerids that may be assigned to the genus or even species level, there are also numerous spicules that clearly belong to the order Poecilosclerida but cannot be assigned to a lower taxonomic unit. These are various punctated oxeas ( Figs. 21 View FIGURE 21 E, F), sigma microscleres ( Figs. 21 View FIGURE 21 J, K), tylotes as well as one isodischelae microsclere ( Fig. 21 View FIGURE 21 I). Other examples of such spicules are acanthoxeas ( Figs. 21 View FIGURE 21 G, H).

Some of these spicules were identified in fossil record. For example, tylotes ( Figs. 21 View FIGURE 21 L, M) were described by Mostler (1972) from the Triassic and Łukowiak et al. (2014) from the Miocene, and sigmas were noted e.g., from the Miocene by Łukowiak et al. (2014).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |