Ranitomeya fantastica, Boulenger, 1884

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3083.1.1 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/1D338788-9572-1568-C8FC-98163C3DFAE4 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe (2021-08-23 20:40:41, last updated by Plazi 2023-11-04 13:58:37) |

|

scientific name |

Ranitomeya fantastica |

| status |

|

Ranitomeya fantastica View in CoL ( Boulenger 1884 “1883”)

Account authors: J.L. Brown, E. Twomey

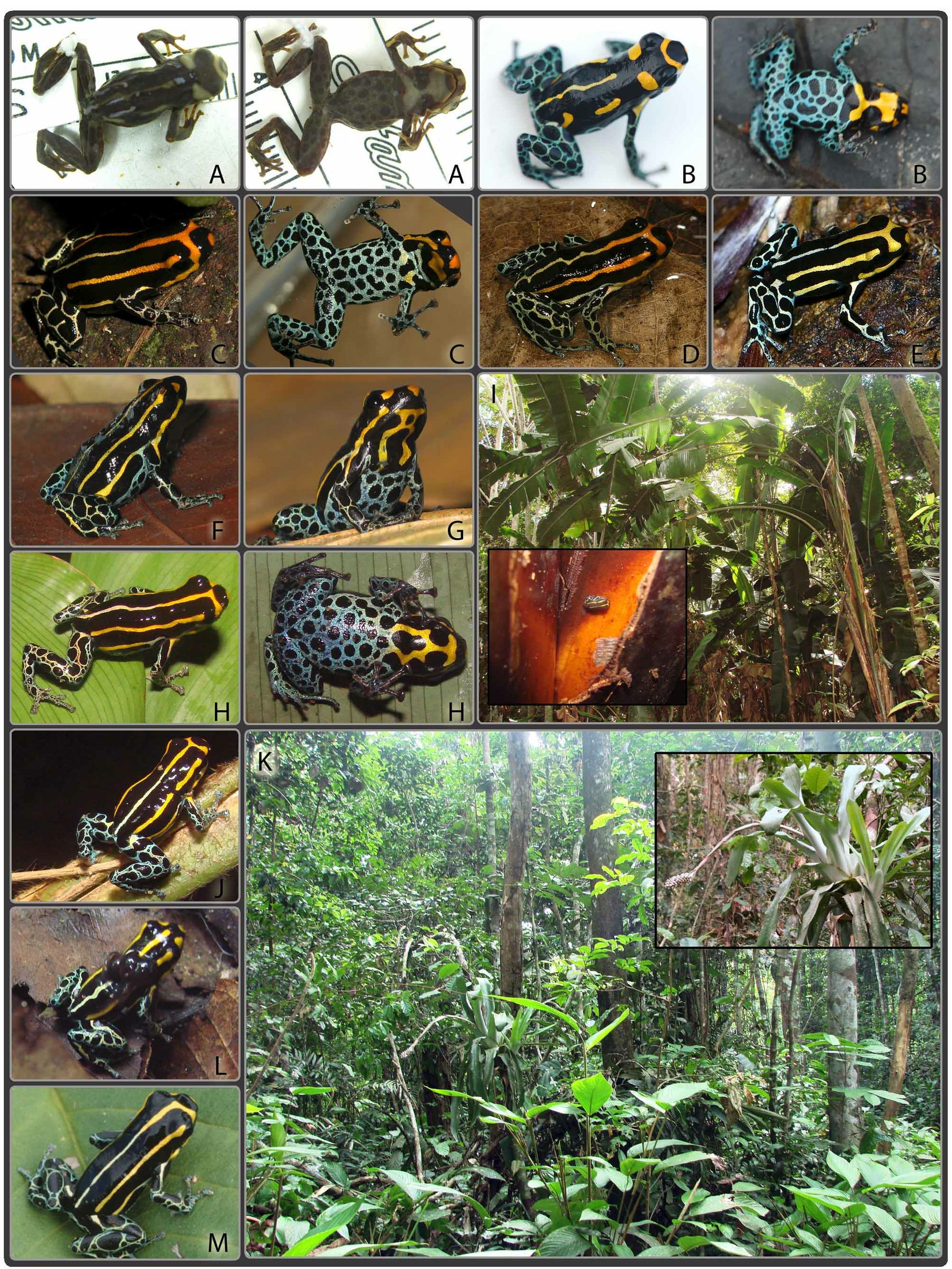

Figs. 3 View FIGURE 3 , 4 View FIGURE 4 , 9 View FIGURE 9 , 15 View FIGURE 15 (e – l), 18, 20

Tables 1 – 6

Dendrobates fantasticus Boulenger 1884 View in CoL “1883”: p. 635, Plate 57, drawing 3 [NHML 1947.2.15.1–4 (four syntypes) collected by Paul Hahnel from “Yurimaguas, Huallaga River, Peru ”]; – Myers 1982: p. 1; Kneller 1983: p. 148; Divossen 1999: p. 58, 2002: p. 20; Schulte 1999 (partim): p. 57, Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 , pattern I, L, M Cordillera Oriental “Alto Cainarachi”, Cordillera Oriental “Achinamisa”, Huallaga River “Reticulated Hybrid?” morphs, (I, L, M, reprinted from Silverstone, 1975); Symula et al. 2001 (partim): p. 2415, Fig. 1 photo E, Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 (phylogenetic tree/drawing); Symula et al. 2003 (partim): p. 452, Table 1, Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 (phylogenetic tree/drawing); Christmann 2004: p. 6, Figs. on p. 37, 159; Santos et al. 2009, by implication

Dendrobates quinquevittatus View in CoL (non Steindachner 1864) – Silverstone 1975 (partim): p. 33, Fig. 14 View FIGURE 14 (drawing), patterns I, L, M

Ranitomeya fantastica View in CoL – Bauer 1988: p. 1; Grant et al. 2006: p. 171, Fig. 76; Lötters et al. 2007 (partim): p. 472, Figs. 588, 590; Brown et al. 2008a: p. 1154; 2008b: p. 5, Fig. 1; 2008c: p. 2, Figs. 1, 3 View FIGURE 3 , 5 View FIGURE 5 , 8–10 View FIGURE 8 View FIGURE 9 View FIGURE 10 ; von May et al. 2008a: p. 394, Appendix 1

Background information. For a summary of current knowledge on this species see Brown et al. (2008c), with the exception of the following comments. Recently, E. Twomey rediscovered a population of R. fantastica View in CoL that exactly matched Boulenger’s description (identical to 3 of 4 types, Fig 15e View FIGURE 15 ) less than 20 km from Boulenger’s stated type locality. Two other populations of R. fantastica View in CoL are known to occasionally lack black crown markings (near Varadero, Loreto and near Yumbatos, San Martin), however both populations bear subtle differences and occur further from the presumed type locality (ca. 40 km NW and 55 km SW, respectively).

In 2008, Karl-Heinz Jungfer discovered a new population of this species in the Cordillera Campanquis near the Pongo de Manseriche, Loreto, Peru. Given its unique morphology and apparently disjunct distribution, we originally suspected that these frogs might represent an undescribed species. However, after performing phylogenetic analyses on sequences collected from these individuals, there is little phylogenetic support for this hypothesis and they appear to simply represent a northern population of R. fantastica . Ironically, the discovery of this population (which is morphologically similar in appearance to R. summersi ), further supports the classification of R. summersi as a separate species from R. fantastica . Based on our phylogeny, a population of R. fantastica that occurs less than 30 km from a population of R. summersi is most closely related to a population of R. fantastica from Pongo de Manseriche. These two populations of R. fantastica are separated by more than 250 km and several mountain ranges, versus less than 30 km and relatively contiguous habitat. This relationship could also be attributed to incomplete lineage sorting and should be further investigated.

The phylogenetic topology of R. fantastica , R. summersi and R. benedicta differs from that published in Brown et al. (2008c). In this study, the lower Huallaga populations of R. fantastica are sister to R. summersi , which form a clade that is sister to R. benedicta ; this entire clade is sister to the rest of the members of R. fantastica . In Brown et al. (2008c), R. summersi was sister to R. fantastica (in which, R. fantastica consisted of two main clades, one containing individuals from the lower Huallaga and an individual from Tarapoto and all individuals from lower Huallaga sister to all other R. fantastica ) and both species were sister to R. benedicta . To clarify these differences, we performed reciprocal topology tests (using Shimodaira-Hasegawa tests, Table 3); each study’s topology was tested on both datasets (note: samples not included in both analyses were left as they were in the unconstrained topology as much as possible). When using the current dataset, which contains fewer base pairs than Brown et al. (2008c), we found no statistical differences in either topologies (p = 0.491) suggesting they are equally probable. The differences in tree length (under Parsimony) were 1. However when using the dataset from Brown et al. (2008c), the Shimodaira–Hasegawa test rejected the topology observed in this study (p = 0.012), supporting the specific relationships observed in Brown et al. (2008c), with individuals from lower Huallaga being members of R. fantastica ). The difference in tree lengths (via Parsimony) between these two tree topologies was 13. Thus, despite the topology of our phylogeny, we maintain that R. benedicta is sister to a clade containing the sister species R. fantastica and R. summersi .

Even though these results support the specific status of the lower Huallaga individuals as R. fantastica ( Brown et al. 2008c; Fig. 15 View FIGURE 15 ), this population’s phylogenetic status (and specific status) is not entirely clear. In other unpublished analyses (based on different datasets), these populations were observed sister to R. summersi (as in this study), and based on morphology we cannot reject this possible relationship (that these populations are members of R. summersi ). To clarify this, additional morphological and sequence data are necessary, using both mitochondrial and nuclear genes, and molecular data should be analyzed using coalescent-based phylogenies.

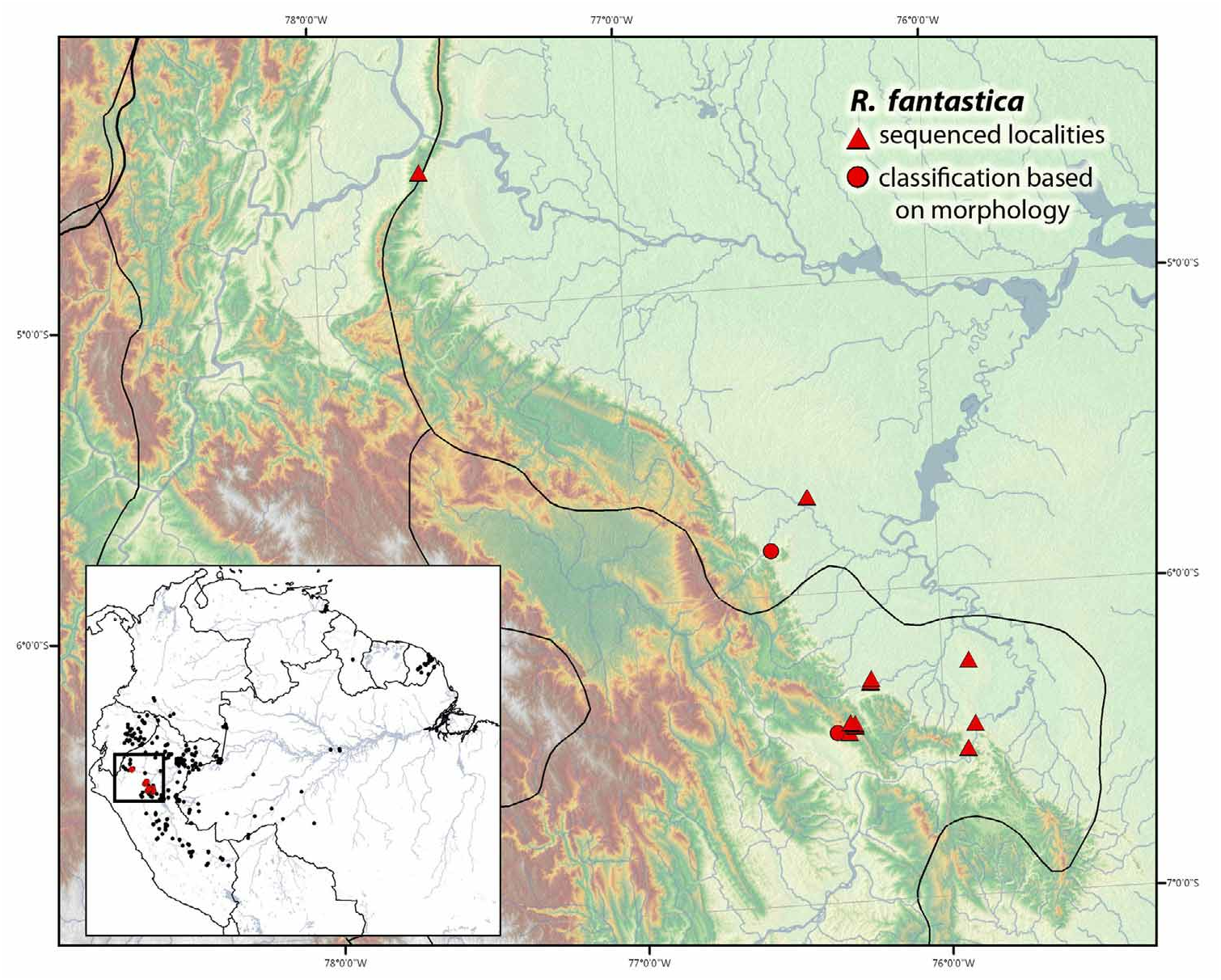

Distribution. This species is known to occur within the departments of Amazonas, Loreto and San Martín, Peru ( Fig. 20 View FIGURE 20 ).

Bauer, L. (1988) Pijlgifkikkers en verwanten: de familie Dendrobatidae. Het Paludarium, 1 Nov, 1988, 1 - 6.

Boulenger, G. A. (1884 1883 ) On a collection of frogs from Yurimaguas, Huallaga River, Northern Peru. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1883, 635 - 638, 1 colour pl, 1 B & W pl.

Brown, J. L., Morales, V. & Summers, K. (2008 a) Divergence in parental care, habitat selection and larval life history between two species of Peruvian poison frogs: an experimental analysis. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 21, 1534 - 1543.

Brown, J. L., Twomey, E., Pepper, M. & Rodriguez, M. S. (2008 c) Revision of the Ranitomeya fantastica species complex with description of two new species from Central Peru (Anura: Dendrobatidae). Zootaxa, 1823, 1 - 24.

Christmann, S. P. (2004) Dendrobatidae - Poison Frogs - A Fantastic Journey through Ecuador, Peru and Colombia (Volumes I, II & III).

Divossen, H. (1999) Dendrobates fantasticus in the field and in the terrarium. Aquarium (Bornheim), 355, 58 - 60.

Grant, T., Frost, D. R., Caldwell, J. P., Gagliardo, R., Haddad, C. F. B., Kok, P. J. R., Means, D. B., Noonan, B. P., Schargel, W. E. & Wheeler, W. (2006) Phylogenetic systematics of dart-poison frogs and their relatives (Amphibia, Athesphatanura, Dendrobatidae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 299, 1 - 262.,

Kneller, M. (1983) Beobachtungen an Dendrobates fantasticus im naturlichen Lebensraum und im Terrarium. Das Aquarium, 16, 148 - 151.

Lotters, S., Jungfer, K. - H., Schmidt, W. & Henkel, F. W. (2007) Poison Frogs: Biology, Species and Captive Husbandry Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt am Main, 668 pp.

Myers, C., W. (1982) Spotted poison frogs: Description of Three new Dendrobates from Western Amazonia, and resurrection of a lost species from Chiriqui . American Museum Novitates, 2721, 23.

Santos, J. C., Coloma, L. A., Summers, K., Caldwell, J. P., Ree, R. & Cannatella, D. C. (2009) Amazonian Amphibian Diversity Is Primarily Derived from Late Miocene Andean Lineages. PLoS Biol, 7, e 1000056.

Schulte, R. (1999) Pfeilgiftfrosche Artenteil - Peru . INBICO, Wailblingen, Germany, 294 pp.

Symula, R., Schulte, R. & Summers, K. (2001) Molecular phylogenetic evidence for a mimetic radiation in Peruvian poison frogs supports a Mullerian mimicry hypothesis. Proccedings of the Royal Sociey of Lond Series B-Biological Science, 268, 2415 - 2421.

Symula, R., Schulte, R. & Summers, K. (2003) Molecular systematics and phylogeography of Amazonian poison frogs of the genus Dendrobates. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 26, 452 - 75.

von May, R., Catenazzi, A., Angulo, A., Brown, J. L., Carrillo, J., Chavez, G., Cordova, J. H., Curo, A., Delgado, A., Enciso, M. A., Gutierrez, R., Lehr, E., Martinez, J. L., Medina-Muller, M., Miranda, A., Neira, D. R., Ochoa, J. A., Quiroz, A. J., Rodriguez, D. A., Rodriguez, L. O., Salas, A. W., Seimon, T., Seimon, A., Siu-Ting, K., Suarez, J., Torres, J. & Twomey, E. (2008 a) Current state of conservation knowledge of threatened amphibian species in Peru. Tropical Conservation Science, 1, 376 - 396.

FIGURE 3. A consensus Bayesian phylogeny based on 1011 base pairs of aligned mitochondrial DNA sequences of the 12S (12s rRNA), 16S (16s rRNA) and cytb (cytochrome-b gene) regions. Thickened branches represent nodes with posterior probabilities 90 and greater, other values are shown on nodes. Taxon labels depict current specific epithet, number in tree, the epithet being used prior to this revision (contained in parentheses), and the collection locality. A. Top segment. B. Middle segment. C. Bottom segment of phylogeny.

FIGURE 4. Putative species tree for Andinobates, Excidobates, and Ranitomeya. Placement of species where molecular data were lacking (A. altobueyensis, A. viridis, A. abditus, A. daleswansoni and R. opisthomelas) was based on morphology. Andinobates altobueyensis and A. viridis were placed as sister taxa due to the absence of dark pigmentation on dorsal body and limbs and overall similar dorsal coloration and patterning. These species were placed as sister to A. fulguritus (sequenced) on the basis of similar dorsal coloration (bright green to greenish-yellow). Andinobates opisthomelas was placed in the bombetes group in a polytomy with A. bombetes and A. virolinensis (both sequenced) due to their similar advertisement calls and morphology, particularly their red dorsal pattern and marbled venter. Andinobates daleswansoni was placed as sister to A. dorisswansonae due to the absence of a well-defined first toe in both species. Andinobates abditus was placed in the bombetes group based on a larval synapomorphy which appears to be diagnostic of that group (wide medial gap in the papillae on the posterior labium). However, A. abditus was placed as the sister species to all other members of the bombetes group due to the absence of bright dorsal coloration and isolated geographic distribution. Andinobates abditus is currently the only species of its genus known to occur in the east-Andean versant, thus its placement remains speculative until molecular data become available. Photo credits: Thomas Ostrowski, Karl-Heinz Jungfer, Victor Luna-Mora, Giovanni Chaves-Portilla.

FIGURE 5. Andinobates Plate 1. minutus group: A–G: Andinobates claudiae and habitat (all from Bocas del Toro, Panama. Photos T. Ostrowski); A & B: Buena Esperanza; C–F: Isla Colon; G: Cerro Brujo; H: tadpole in phytotelm; I: habitat in Bocas del Toro, Panama. J–M: Andinobates minutus (all from Colombia. Photos DMV unless noted): J & K: Buenaventura, Valle del Cauca; L: Quibdó, Chocó; M: Baudó, Chocó (photo J. Mejía-Vargas). fulguritus group: N–V: Andinobates fulguritus (all from Colombia, photos DMV unless noted): N: Baudó, Chocó (photo J. Mejía-Vargas); O: Playa de Oro, Chocó (type locality); P–R: Uraba, Chocó. S–V: Anchicayá, Valle del Cauca. (nΦ = number of individual in phylogeny, Ω = population sampled in phylogeny).

FIGURE 8. Advertisement calls for species of Andinobates. A. Andinobates bombetes from Bosque Yotoco, Valle del Cauca, Colombia (type locality), recorded at 18-20° C; B. Andinobates claudiae from Isla Colón, Panama, recorded at 25° C (call courtesy Thomas Ostrowski); C. Andinobates fulguritus from Itauri, Colombia, unknown temperature; D. Andinobates fulguritus from Kuna Yala, Panama, recorded in captivity at 24° C (call courtesy T. Ostrowski); E. Andinobates dorisswansonae from “El Estadero”, Caldas, Colombia (type locality), recorded at 19-20° C; F. Andinobates minutus, unknown locality or temperature; G. Andinobates opisthomelas from Guatapé, Antioquia, Colombia, unknown temperature.

FIGURE 9. Known elevation distributions of Ranitomeya. Dotted line is mean for all samples. Dark boxes display the total elevation range of each species, within each contains a corresponding box plot.

FIGURE 10. Ranitomeya Plate 1. defleri group: A–B: Ranitomeya defleri (all from Vaupés, Colombia); A: Holotype at MCZ (Ω); B: near Estación Biológica Caparú (1 Φ). C–M: Ranitomeya toraro from Brazil; C–D: Careiro da Varzea, Amazonas (A. P. Lima); E: Humaitá, Amazonas (P. I. Simoes); F–G: Cachoiera do Jirau, Rondônia (W. Hödl); H: near Boca do Acre, Amazonas (PRMS and MBS, Ω); I: Host plant of R. toraro: Phenakospermum guyanense near Boca do Acre, Acre (MBS); J: near Boca do Acre, Amazonas (PRMS and MBS); K: Habitat of R. toraro near Boca do Acre, Acre, inset: Aechmea sp. used for tadpole deposition (MBS); L: near Boca do Acre, Amazonas (PRMS and MBS); M: Rio Ituxi, Amazonas (JPC, Ω). (nΦ = number of individual in phylogeny, Ω = population sampled in phylogeny).

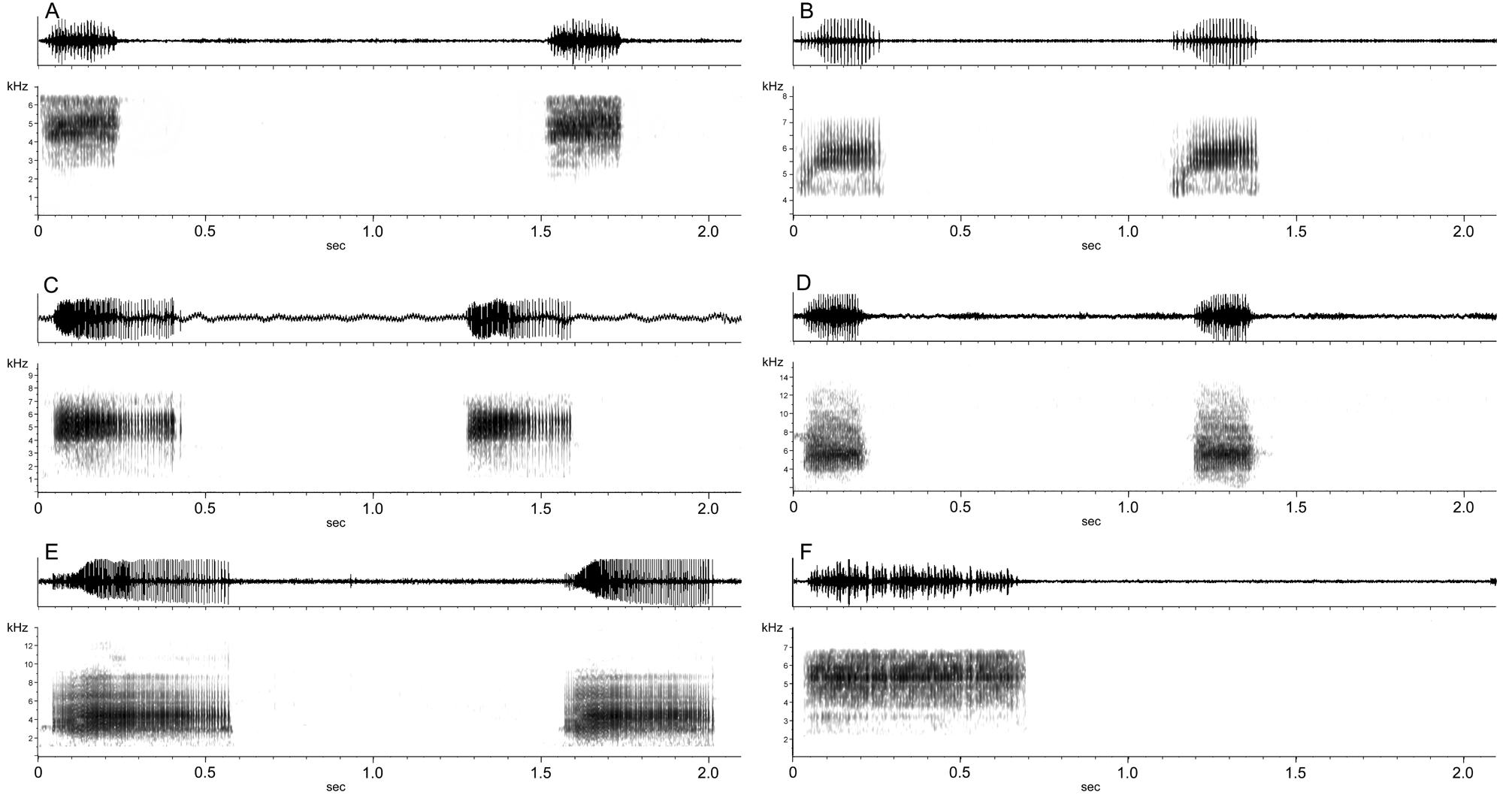

FIGURE 14. Advertisement calls of Ranitomeya species in the variabilis group and defleri group. A. Ranitomeya amazonica from 23 km S Iquitos, Loreto, Peru (type locality), recorded at 26° C; B. Ranitomeya amazonica from French Guiana, unknown temperature (call courtesy Erik Poelman); C. Ranitomeya variabilis from Cainarachi valley, San Martín, Peru, recorded at 22° C. D. Ranitomeya variabilis from Cerro Yupatí, Amazonas, Colombia, recorded at 27° C; E. Ranitomeya variabilis from Saposoa, San Martín, Peru, recorded at 24.5 C; F. Ranitomeya defleri from Rio Apaporis, Vaupés, Colombia, recorded at 26° C.

FIGURE 15. Ranitomeya Plate 3. reticulata group: A–D: Ranitomeya benedicta (all from Peru); A–B: Shucushuyacu, Loreto (1Φ); C-D: Pampa Hermosa, Loreto. E–L: Ranitomeya fantastica (all from Peru); E: Yurimaguas, Loreto; F: near Yumbatos, San Martin; G: Pongo de Cainarachi, San Martin (Ω); H: Cainarachi Valley, San Martin (Ω); I: San Antonio, San Martin (KS); J: Tarapoto, San Martin (Ω); K: Santa María de Nieva, Loreto (K.-H. Jungfer, 1Φ); L: Lower Huallaga Canyon, San Martin (Ω). M & N: Ranitomeya summersi (all from San Martin, Peru); M: Chazuta (3Φ); N: Sauce (Ω). O–R: Ranitomeya reticulata (all from Loreto, Peru); O-P: Iquitos (Ω); Q: Puerto Almendras (PPP); R: Upper Rio Itaya (PPP). (nΦ= number of individual in phylogeny, Ω = population sampled in phylogeny).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Ranitomeya fantastica

| Brown, Jason L., Twomey, Evan, Amézquita, Adolfo, Souza, Moisés Barbosa De, Caldwell, Jana- Lee P., Lötters, Stefan, May, Rudolf Von, Melo-Sampaio, Paulo Roberto, Mejía-Vargas, Daniel, Perez-Peña, Pedro, Pepper, Mark, Poelman, Erik H., Sanchez-Rodriguez, Manuel & Summers, Kyle 2011 |

Ranitomeya fantastica

| Brown, J. L. & Morales, V. & Summers, K. 2008: 1154 |

| von May, R. & Catenazzi, A. & Angulo, A. & Brown, J. L. & Carrillo, J. & Chavez, G. & Cordova, J. H. & Curo, A. & Delgado, A. & Enciso, M. A. & Gutierrez, R. & Lehr, E. & Martinez, J. L. & Medina-Muller, M. & Miranda, A. & Neira, D. R. & Ochoa, J. A. & Quiroz, A. J. & Rodriguez, D. A. & Rodriguez, L. O. & Salas, A. W. & Seimon, T. & Seimon, A. & Siu-Ting, K. & Suarez, J. & Torres, J. & Twomey, E. 2008: 394 |

| Grant, T. & Frost, D. R. & Caldwell, J. P. & Gagliardo, R. & Haddad, C. F. B. & Kok, P. J. R. & Means, D. B. & Noonan, B. P. & Schargel, W. E. & Wheeler, W. 2006: 171 |

| Bauer, L. 1988: 1 |