Dinomys branicku, Peters, 1873

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6599657 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6599220 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/1A1087DF-FFBD-FFEF-B120-F9E0E7169BB0 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Dinomys branicku |

| status |

|

Pacarana View Figure

French: Pacarana / German: Pakarana / Spanish: Pacarana

Taxonomy. Dinomys branickii Peters, 1873 View in CoL ,

“in der Colonie Amable Maria, in der Montana de Vitoc, in den Hochgebirgen Perus erlegt” (= from Amable Maria, in the Montana de Vitoc, in the high mountains of Peru), Department ofJunin, Peru .

This species is monotypic.

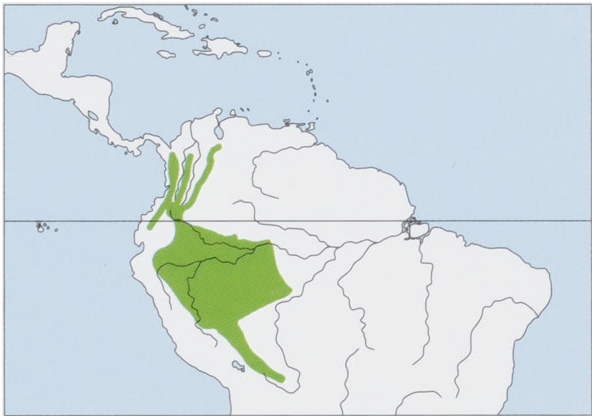

Distribution. W Venezuela (Mérida Andes), W & S Colombia (all three Andean Cordilleras), N Andean slopes and Amazon Basin in Ecuador, and E Andean slopes and W Amazon Basin in E Peru, W Brazil, and WC Bolivia. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 730-790 mm, tail 140-230 mm, ear 30-45 mm, hindfoot 114-123 mm; weight 7.3-15 kg. The Pacarana is blackish or brownish dorsally, lighter ventrally. Two color phases are present suggesting that sexes may be dichromatic, with adult males black and females brown. Two longitudinal rows of white spots on each side of midline beginning at shoulders may appear as broad, more-or-less continuous stripes. White spots on sides of body, flanks, and thighs may appear as two shorter rows or be irregularly scattered. Stripes may be broader and whiter in older adults. Pelage is coarse, and hairs vary in length. Tail is thick and well furred. Vibrissae are white and long, about the length of head. Differences in size and degree offusion of bones and sutures suggest that males and females are sexually dimorphic. Skull is large and nearlyflat in dorsal profile. Zygoma is thick and heavy and lacks a jugal fossa; jugal does not join lacrimal; lacrimal canal does not open on side of rostrum. Infraorbital foramen is large and lacks a ventral groove. Paraoccipital process is short. Angular process of dentary is strongly deflected; coronoid process is reduced. Maxillary tooth rows are strongly convergent anteriorly. Cheekteeth are composed of four transverse laminae; upper cheekteeth have the two anterior laminae isolated and the posterior two laminae united; lower cheekteeth exhibit the reverse pattern. Permanent teeth replace deciduous premolars; this pattern is found in most mammals but not all hystricomorph rodents.

Habitat. Andean and tropical montane wet forest and some part of the periodically flooded Amazonian rainforest, particularly at lower and middle elevations, but also up to 3400 m. The Pacarana inhabits primary and secondary forest, frequenting vegetation along streams or creeks, but it also is found in disturbed areas such as croplands and montane coffee plantations. It prefers areas with large rocks, tree trunks, and fallen logs (for shelters) and steep slopes on hillsides or mountainsides.

Food and Feeding. The Pacarana is a generalist herbivore, eating a wide variety of plants and plant parts, including leaves, stems, fruits, nuts, roots, and rhizomes. In captivity, it will eat vegetables and fruits but also grains and domestic animal chow. In agricultural areas, Pacarana disturb fields of corn and potatoes, among others.

Breeding. Little is known about breeding and reproduction ofwild Pacaranas; nearly all information has been obtained from captive individuals. The Pacarana does not appear to have a defined breeding season, and births have occurred throughout the year. Gestation is 223-283 days but typically does not exceed 252 days. Females give birth to 1-4 young, each weighing 570-900 g. Sex ratio at birth is 1:1.

Activity patterns. The Pacarana is a large rodent, butit is rarely observed in the wild. Sign (e.g. tracks, trails, and droppings), camera traps, and interviews with local people have been used to determine presence. The Pacarana is nocturnal and crepuscular and spends the majority of the day sleeping or resting in caves or dens. Time spent actively excavating caves or dens is limited because the Pacarana preferentially uses natural caves and crevices. The Pacarana does not exclusively use a single den but frequently changes locations of den sites. In captivity, even when other burrows are available, up to eight Pacaranas will use the same burrow. In captivity, the Pacarana shows little activity during rainy periods but will emerge from the burrow to forage. Activity is high at 18:00 h and diminishes during the night until 22:00 h, two additional peaks ofactivity occur around midnight and pre-dawn, and activity slowly declines until dawn. Morphology suggests that the Pacarana is semi-arboreal; this includes musculature to forelimbs and hindlimbs being about equal, low proportion of back extensor muscles, limb muscles not aligned or developed for linear propulsive thrust. Climbing ability may be more prominent in young individuals, and use of tail to climb likely decreases as age increases.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Presence of multiple burrows and burrow systems are central to the home range of a Pacarana group. Burrows are located in areas ofsloping, rocky outcrops and are connected to latrines and foraging areas by a systemoftrails often made through dense vegetation. Pacarana groups have home ranges of 5-12 ha, with 5-10 groups/km?®. Pacaranas apparently form extended family units of a pair of adults and 2—4 offspring. Such groups also have been observed occasionally in the wild. Pacaranas are docile to one another and seldom act aggressively, even in captivity. Nevertheless, interactions during feeding can lead to aggressive encounters, which may help establish a dominance order. Exploring, grooming, and feeding are the major behaviors of Pacaranas. Maintenance behavior is most frequent in females, who also spend more time out of the burrow and have more frequent social contact with other individuals. Marking activities, which are done by males, are not pronounced but help define individual and group space.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. The Pacarana is Vulnerable due to an estimated population decline of more than 30% since 1998. The most serious threats facing the Pacarana are overexploitation from illegal hunting for food and commercial trafficking ofskins and loss of forest habitat due to habitat destruction and degradation. Research on the Pacarana in the wild has been uncommon, and they are generally considered to be rare throughout their distribution. Apparent rarity may reflect low densities, particularly where humans hunt them and modify habitat, or be due, in part, to occurrence in habitats that are difficult to access. Apparent rarity may also reflect a lack of knowledge of habits and habitat. Burrow availability also may be a major factor limiting distribution and abundance of Pacaranas. Almost all published research on the Pacarana has been based on captive individuals in zoos, biological parks, and research colonies. Pacaranas are difficult to maintain in captivity, and mortality of young is high for unknown reasons. Nevertheless, research on captive individuals provides important information on habits, natural history, and reproduction of the Pacarana that could enhanceits conservation in the wild.

Bibliography. Alberico et al. (2000), Azurduy & Langer (2006), Boher & Marin (1988), Caro (2013), Castano et al. (2003), Collins & Eisenberg (1972), Eisenberg (1974), Figueroa (2014), Giraldo-Canas (2001), Goeldi (1904), Gonzalez & Osbahr (2013), Grand & Eisenberg (1982), Grimwood (1969), Huchon & Douzery (2001), Kleiman (1974), Linares (1998), Lonnberg (1921), Lopez et al. (2000), Lord (1999), Meritt (1984), Mones (1981), Munoz (2003), Nasif (2010), Nasif & Abdala (2015), Opazo (2005), Osbahr (1998, 1999, 2010), Osbahr & Azumendi (2009), Osbahr & Restrepo (2001), Osbahr et al. (2009), Parra (2001), Peters (1873a, 1873b), Ramirez-Chaves et al. (2008), Rinderknecht & Blanco (2008), Rodriguez & Rojas-Suarez (1999), Saavedra-Rodriguez, Corrales-Escobar & Giraldo-Lopez (2014), Saavedra-Rodriguez, Kattan et al. (2012), Saavedra-Rodriguez, Osbahr et al. (2012), Sanborn (1931), Sierra-Giraldo & EscobarLasso (2014), Solari et al. (2013), Tirira, Vargas & Dunnum (2008), Upham & Patterson (2012), Velandia (2012), Weir (1974), White & Alberico (1992).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.