Sertularella gaudichaudi ( Lamouroux, 1824 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.213236 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3512232 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/170887E3-F44F-1615-FF19-49E2EEA925C7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Sertularella gaudichaudi ( Lamouroux, 1824 ) |

| status |

|

Sertularella gaudichaudi ( Lamouroux, 1824)

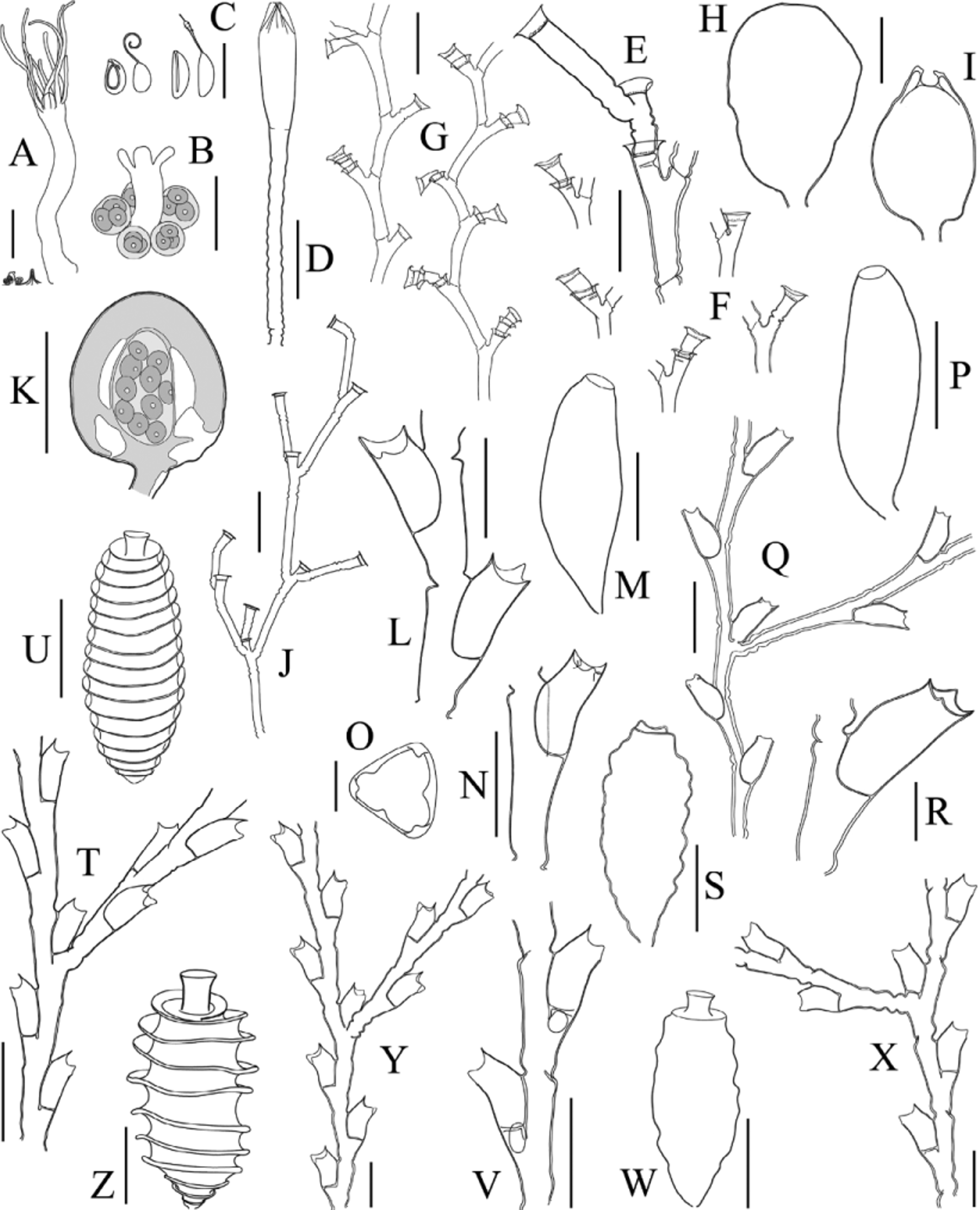

(Pl. 1R, Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2. A – C Q–S)

Sertularia Gaudichaudi Lamouroux, 1824: 615 View in CoL , pl. 90 figs 4, 5.

Sertularella Gaudichaudi — Kirchenpauer, 1884: 38. — Billard, 1909: 317, figs 5, 6.

Sertularella gaudichaudi — Hartlaub, 1905: 644, fig. K4. — Billard, 1922: 103, figs 1, 2A. — Van Praët, 1979: 901, fig. 47. — Ramil et al., 1992: 518, fig. 15.

Sertularia picta Meyen, 1834: 201 , pl. 24 figs 1–3 (syn. nov.).

Sertularella picta — Hartlaub, 1901: 77, pl. 5 fig. 14, pl. 6 figs 17, 18, 20. — Nutting, 1904: 90, pl. 20 figs 5–7. — Hartlaub, 1905: 645, fig. L4. — Jäderholm, 1903: 282. — Stechow, 1919: 24, fig. 3. — Stechow, 1923: 187, fig. B1. — Billard, 1922: 106, fig. 2B. — Naumov & Stepanjants, 1962: 88. — Blanco, 1963: 175. — Blanco, 1967b: 112, pl. 3 figs 1–7. —? Vervoort, 1972a (pro parte): 111, fig. 34C. — Millard, 1977: 25, fig. 6A–D. — Stepanjants, 1979: 85, pl. 15 fig. 4. — Ramil et al., 1992: 520. — El Beshbeeshy, 2011: 138, fig. 44.

not Sertularella picta — Millard, 1971, 405, fig. 6A, B (= S. antarctica Hartlaub, 1901 ).

Sertularella gigantea — Billard, 1906: 12, fig. 4 (not S. gigantea Mereschkowsky, 1878 ).

? Sertularia polyzonias — Vanhöffen, 1910: 322, fig. 32 [not Sertularella polyzonias ( Linnaeus, 1758) ].

Sertularella polyzonias — Blanco, 1984: 37, pls 31–36 figs 69–81 [not Sertularella polyzonias ( Linnaeus, 1758) ].

Sertularella sanmatiasensis —Peña Cantero, 2006: 939, fig. 3L. — Peña Cantero & Gili, 2006: 767. — Peña Cantero, 2008: 459, fig. 2C. — Peña Cantero & Vervoort, 2009: 87, fig. 2B — Peña Cantero, 2012: 858, fig. 4A (not S. sanmatiasensis El Beshbeeshy, 2011 ).

not Sertularella sanmatiasensis — Galea et al., 2009: 12 View Cited Treatment , fig. 3C–E [= Sertularella mixta Galea & Schories, 2012 ].

Material examined. Stn. PNS — 16.ii.2010, Ant.09/2010 (12 m): a luxuriant, sterile colony, ca. 9 cm high, on bryozoan (MHNG-INVE-79785); 07.ii.2011, Ant.02/2011 (7 m): numerous sterile stems, up to 4 cm high, on gravel (MHNG-INVE-79774); Ant.05/2011 (7 m): numerous sterile stems, up to 3 cm high, on fine gravel and bryozoan (MHNG-INVE-79782). Stn. RAS — 11.ii.2010, Ant.01/2010 (30 m): colony with six sterile stems, 0.6– 3.0 cm high; 12.ii.2010, Ant.08/2010 (10–40 m): several stems up to 4 cm high, one bearing a female gonotheca, on bryozoan; 21.ii.2011, Ant.03/2011 (15–20 m): numerous stems, up to 10 cm high, some bearing female gonothecae (MHNG-INVE-79776); Ant.12/2011 (15–20 m): luxuriant colony composed of numerous stems, up to 6.5 cm high, richly bearing female gonothecae, on sponge (MHNG-INVE-79773); Ant.14/2011 (20–30 m): a few sterile stems, 0.7–2.0 cm high, on seaweed.

Remarks. The present material agrees in every respect with the holotype of S. gaudichaudi redescribed by Billard (1909, 1922). The branching pattern is typically irregular (Pl. 1R) and the hydrothecae are shifted on to the anterior side of the colonies. Internodes are long (730–1335 µm) with respect to the adnate side of the hydrothecae; the latter are 325–350 µm wide, their free adaxial side is 470–570 µm long, the adnate part 320–375 µm, the abaxial wall is 705–770 µm, and the diameter at aperture is 255–295 µm. Intrathecal projections of perisarc (one abcauline and two latero-adcauline) are irregularly seen among the hydrothecae of a colony. The gonothecae, female in the fertile samples examined, are 2500–2950 µm long and 950–1180 µm wide.

The taxonomy of S. gaudichaudi proves to be a complex one, and strongly calls to mind that of S. antarctica Hartlaub, 1901 , for which several species, characterized by morphological features of likely no taxonomical importance, have been created. Moreover, these two species are morphologically related and both are characterized by the hydrothecae being shifted on to the anterior side of the colonies, flask-shaped, conspicuously swollen on the adaxial side, with normally a thickened rim, and three, more or less conspicuous intrathecal projections of perisarc. Chief differences between them lie in the growth habit [regularly alternate side branches in S. antarctica (see Pl. 3D in Galea & Schories 2012) vs. an irregular branching pattern in S. gaudichaudi (Pl. 1R in the present account)] and the shape of hydrotheca, which is comparatively elongated and slender in Lamouroux' species.

These characteristic features were not expressly stated or accurately figured in a number of ancient accounts describing new species, making reliable comparisons impossible, thus preventing resolution of their intricate taxonomy. Several species, such as S. contorta Kirchenpauer, 1884 , S. novarae Marktanner-Turneretscher, 1890 , S. paessleri Hartlaub, 1901 , and S. protecta Hartlaub, 1901 , will certainly be sunk into the synonymy of either S. antarctica or S. gaudichaudi . We strongly believe that the above mentioned nominal species are either identical to, or no more than phenotypic variations of one of S. antarctica or S. gaudichaudi . Re-examination of the types (if still extant), as well as a comparative study based on extensive material from the Antarctic and the sub-Antarctic, are imperative.

One species, however, coming very close to S. gaudichaudi is S. picta ( Meyen, 1834) . In contrast to Hartlaub (1901), Billard (1922) expressed doubts regarding their possible conspecificity, arguing that the latter is distinguished by the strongly hypertrophied abaxial hydrothecal cusp (reminiscent of Amphisbetia , according to Stechow 1919), a much thickened rim, more prominent intrathecal cusps, and the formation of a perisarc plug at the junction between the adnate adaxial wall and the base of hydrotheca. Additionally, Hartlaub (1901) noted the very long internodes on both the main stem and side branches.

Fortunately, there are several modern, reliable accounts of S. picta that demonstrate that the features listed above are not met with systematically. For example, Blanco (1963) found hydrothecae with thickened walls and rim, a prominent abcauline cusp, and internal, submarginal perisarc projections of varied development, while the specimens examined by El Beshbeeshy (2011) had thin-walled hydrothecae, unthickened rim and no intrathecal cusps. Millard (1977) reported on colonies with hydrothecal cusps equally developed in most hydrothecae, while several others exhibited an abcauline cusp produced so that the margin was tilted towards the stem. Finally, Blanco (1967b) assigned to S. picta specimens with the same growth habit as that illustrated by Billard (1922) for the holotype of S. gaudichaudi , though exhibiting some minor differences, such as the thin-walled hydrothecae, with unthickened rim and no internal cusps.

Through the courtesy of A. L. Peña Cantero, one of us (HRG) was able to examine one of his Antarctic specimens (from Low Island, Stn. Low 44, 82 m) assigned to S. sanmatiasensis El Beshbeeshy, 2011 . This material proved indistinguishable from our specimens from King George Island, and it is here assigned to the synonymy of S. gaudichaudi . Moreover, all the previous Antarctic records credited to S. sanmatiasensis should be considered as belonging to the present species.

Sertularella sanmatiasensis superficially resembles S. gaudichaudi , but it is of a comparatively smaller habit, has shorter internodes (with respect to the adnate side of their corresponding hydrothecae), less elongated thecae, with a much longer portion adnate to the internode, a proximally wrinkled free adaxial wall, no neck region, and an abcauline cusp never hypertrophied. Additionally, S. sanmatiasensis has a bright-orange perisarc and the hydranths are reddish-brown, the colors being preserved even in the fixative.

According to the reasons discussed above, we state the following: 1) S. picta is a junior synonym of Lamouroux' (1824) species; 2) two members of Sertularella , viz. S. gaudichaudi and S. antarctica , occur abundantly and are geographically widespread in the sub-Antarctic, the former also penetrating well into the Antarctic.

Geographical distribution. The species spreads from Mar del Plata ( Blanco 1967b) southwards to Tierra del Fuego ( Hartlaub 1901, Jäderholm 1903, Billard 1922, Naumov & Stepanjants 1962). Additional subantarctic records are from around the Falkland Islands ( Lamouroux 1824, Meyen 1834, El Beshbeeshy 2011), the Kerguelen and Crozet shelves ( Millard 1977), and from off Bouvet Is. ( Peña Cantero & Gili 2006). Antarctic records are from the South Shetland islands ( Stepanjants 1979; Peña Cantero 2006, 2009; present study), off Low Is. ( Blanco 1984; Peña Cantero & Vervoort 2009), Trinity Is. ( Peña Cantero 2008), Booth (Wandel) Is. ( Billard 1906), Bellinghausen Sea ( Peña Cantero 2012).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Sertularella gaudichaudi ( Lamouroux, 1824 )

| Galea, Horia R. & Schories, Dirk 2012 |

Sertularella sanmatiasensis

| Pena 2012: 858 |

| Pena 2009: 87 |

| Pena 2008: 459 |

| Pena 2006: 767 |

Sertularella polyzonias

| Blanco 1984: 37 |

Sertularia polyzonias

| Vanhoffen 1910: 322 |

Sertularella gigantea

| Billard 1906: 12 |

Sertularella gaudichaudi

| Ramil 1992: 518 |

| Van 1979: 901 |

| Billard 1922: 103 |

| Hartlaub 1905: 644 |

Sertularella picta

| El 2011: 138 |

| Ramil 1992: 520 |

| Stepanjants 1979: 85 |

| Millard 1977: 25 |

| Blanco 1967: 112 |

| Blanco 1963: 175 |

| Naumov 1962: 88 |

| Stechow 1923: 187 |

| Billard 1922: 106 |

| Stechow 1919: 24 |

| Hartlaub 1905: 645 |

| Nutting 1904: 90 |

| Jaderholm 1903: 282 |

| Hartlaub 1901: 77 |

Sertularella

| Billard 1909: 317 |

| Kirchenpauer 1884: 38 |

Sertularia picta

| Meyen 1834: 201 |

Sertularia Gaudichaudi Lamouroux, 1824 : 615

| Lamouroux 1824: 615 |