Tasmanicosa godeffroyi ( L. Koch, 1865 ) L. Koch, 1865

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4213.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9C76B987-3897-4666-87EF-62EB5BF5CF04 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5676923 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0B32B23C-7B14-9F6F-BEF8-39B6FEB0FEDB |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Tasmanicosa godeffroyi ( L. Koch, 1865 ) |

| status |

comb. nov. |

Tasmanicosa godeffroyi ( L. Koch, 1865) View in CoL comb. nov.

Garden wolf spider

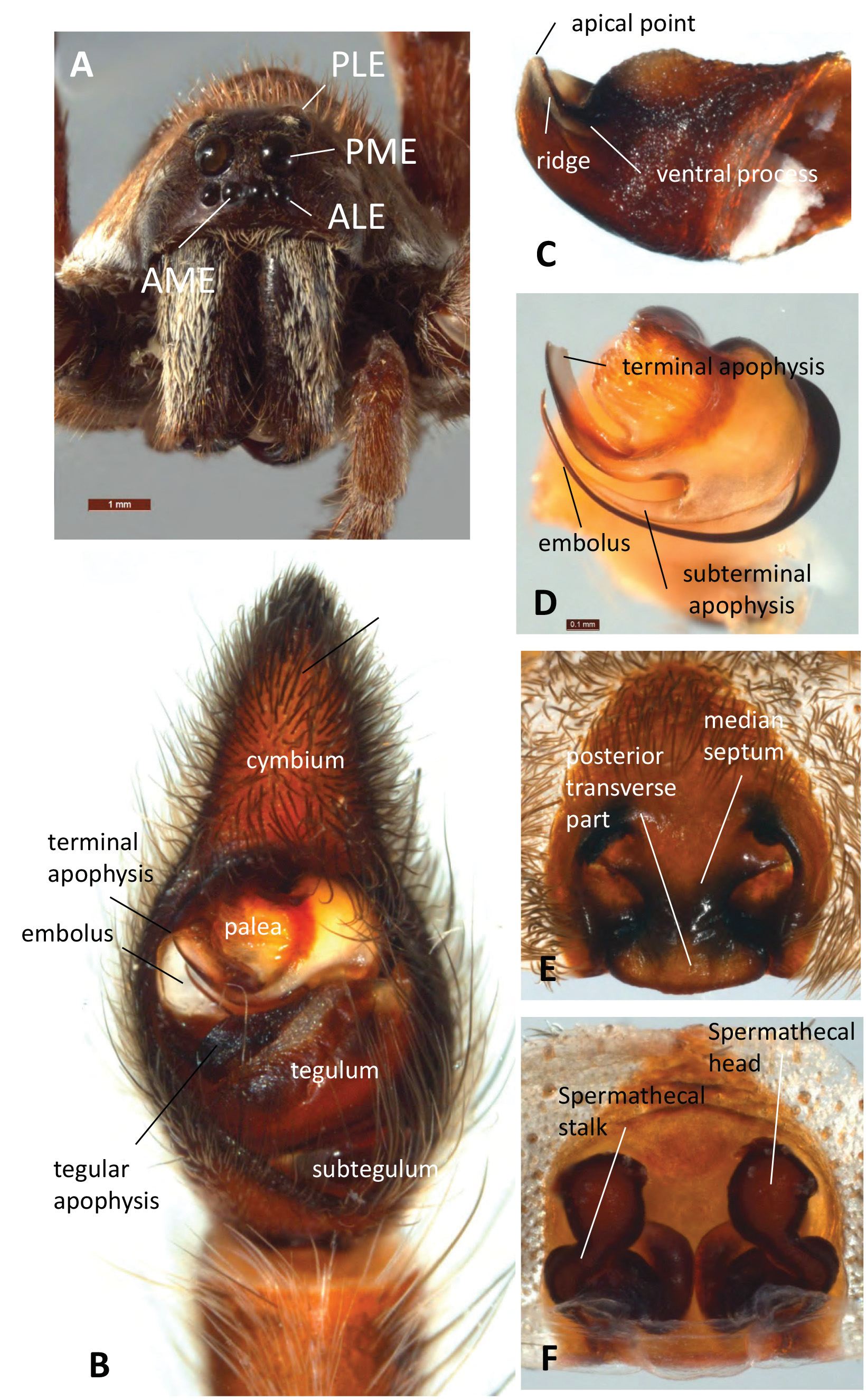

( Figs 1A View FIGURE 1 , 2A–F View FIGURE 2 , 3M View FIGURE 3 , 4A, C View FIGURE 4 , 5A–K View FIGURE 5 , 6A View FIGURE 6 , 7E View FIGURE 7 , 8 View FIGURE 8 )

Lycosa godeffroyi L. Koch, 1865: 867 View in CoL .— L. Koch 1877: 957 –959, plate 83, figs 3, 3A, 4, 4A; Hogg 1900: 77; Rainbow 1911: 268; Rainbow 1917: 488; Main 1964: 120, figs B–D; McKay 1985: 77 –78; Moritz 1992: 314; Platnick 1993: 487. Lycosa bellatrix L. Koch, 1865: 866 (synonymised in L. Koch 1877: 957).

Lycosa tasmanica Hogg, 1905: 571 –573, figs 80, 80 A–B.— Rainbow 1911: 273; Hickman 1967: 79 –80, figs 140, 141, pl. 13, fig. 2; McKay 1973: 380; McKay 1985: 84. New synonymy.

Tarentula godeffroyi (L. Koch) .— Strand 1907: 216.

Tarentula zualella Strand, 1907: 218 –219. New synonymy.

Lycosa woodwardi Simon, 1909: 182 –183.— Rainbow 1911: 274; McKay 1973: 380; McKay 1985: 84; Moritz 1992: 329. New synonymy.

Lycosa zualella (Strand) .— Rainbow 1911: 274; McKay 1973: 380; McKay 1985: 84.

Allocosa woodwardi (Simon) .— Roewer 1955: 207; Rack 1961: 39.

Allocosa zualella (Strand) .— Roewer 1955: 207.

Dingosa tasmanica (Hogg) .— Roewer 1955: 240.

Geolycosa godeffroyi (L. Koch) .— Roewer 1955: 243; Rack 1961: 38; McKay 1973: 380.

Tasmanicosa tasmanica (Hogg) View in CoL .— Roewer 1959: 351.

Type data. Holotype of Lycosa godeffroyi L. Koch. Female with eggsac, Wollongong [34°25’S, 150°53’E, New South Wales, AUSTRALIA] ( Museum Godeffroy ) (not examined; whereabouts unknown; see Remarks below). GoogleMaps

Holotype of Lycosa bellatrix L. Koch. Female, Sydney [33°53’S, 151°13’E, New South Wales, AUSTRALIA] ( Museum Godeffroy ) (not examined; whereabouts unknown; see Remarks below). GoogleMaps

Holotype of Lycosa tasmanica Hogg. Female , Table Cape [40°57’S, 145°43’E, Tasmania, AUSTRALIA], Mr Dove, 1898 ( SAM NN382) (examined). GoogleMaps

Holotype of Tarentula zualella Strand. Male , Sydney [33°53’S, 151°13’E, New South Wales, AUSTRALIA], Herborn ( MWNH) GoogleMaps . Not examined, not listed in type catalogue of the MWNH ( Jäger, 1998).

Syntypes of Lycosa woodwardi Simon. Female, Northampton [28°20’S, 114°37’E, Western Australia, AUSTRALIA] GoogleMaps . 'Hamburger südwest-australische Forschungsreise', 'Station 71', 15 July 1905 ( ZMH, Rack (1961) - catalogue 483); female, 3 juveniles, Beverley [32°06’S, 116°55’E Western Australia, AUSTRALIA] GoogleMaps . 'Hamburger südwest-australische Forschungsreise', 'Station 156', 26 August 1905 ( ZMB 11100); female, same locality, ' Hamburger südwest-australische Forschungsreise', ' Station 156' GoogleMaps , 26 August 1905 ( MHNP 24358 View Materials ). 1 female, Dongara [29°15’S, 114°55’E, Western Australia, AUSTRALIA] GoogleMaps . 'Hamburger südwest-australische Forschungsreise', 'Station 83' (WAM 11/4300) (all examined).

Other material examined. 742 males, 843 females (55 with eggsac) and 131 juveniles in 1,105 records (Appendix B).

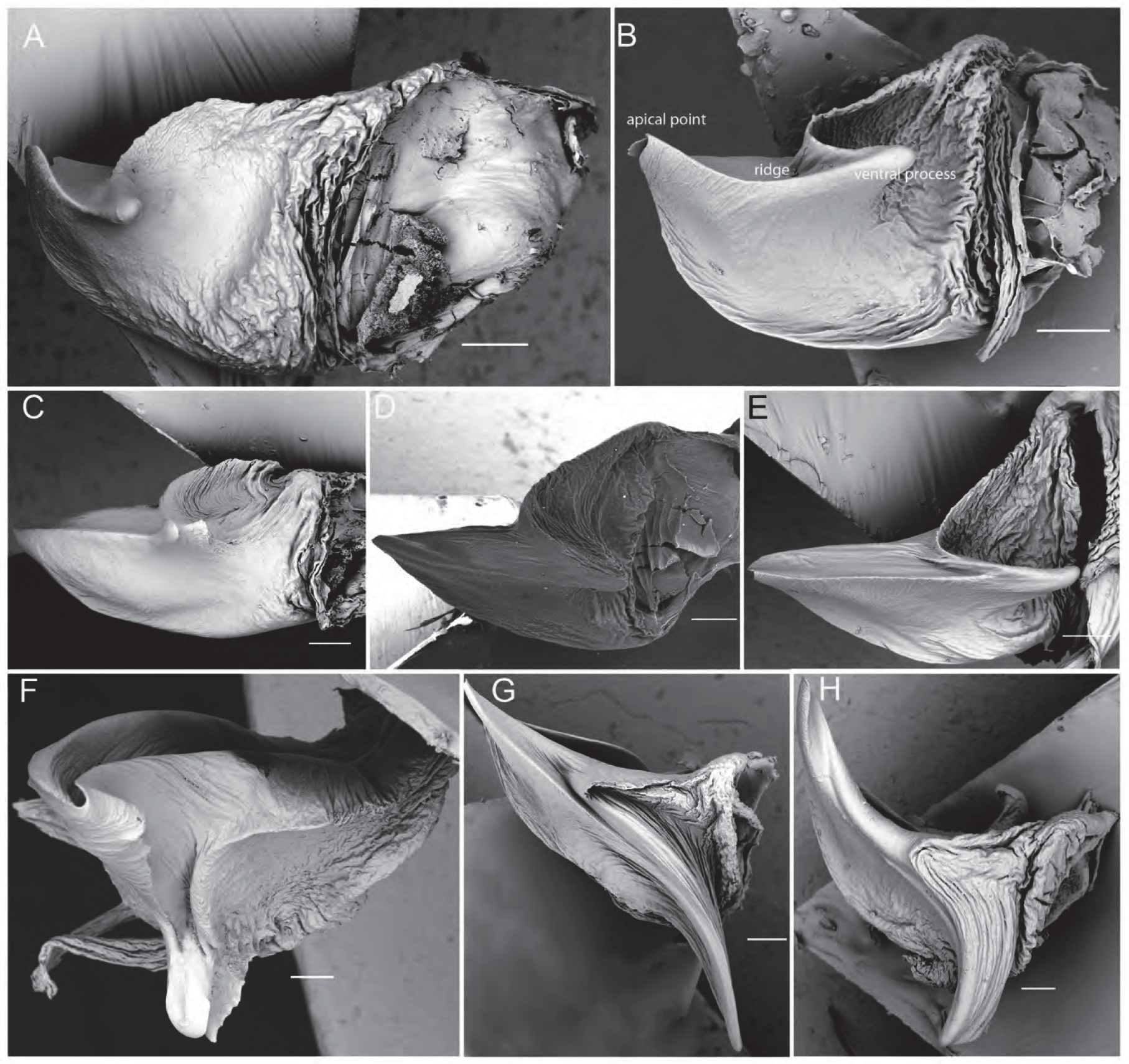

Diagnosis. Males of T. godeffroyi have a very short ridge of the tegular apophysis; it is less than half the width of the tegular apophysis ( Fig. 3M View FIGURE 3 ). Males of T. kochorum are most similar, but their ridge of the tegular apophysis reaches over half the width of the tegular apophysis ( Fig 3Q View FIGURE 3 ). Females resemble T. kochorum ( Fig. 4F View FIGURE 4 ) and T. hughjackmani ( Fig. 4E View FIGURE 4 ) in their epigynal structure; the former has a medially bulging median septum (bulge absent in T. godeffroyi ) and the latter has a median septum that is anteriorly wider than the posterior transverse part (as wide as posterior transverse part in T. godeffroyi ).

Description. Male (based on NMV K11547 View Materials ).

Total length 18.2.

Prosoma. Length 10.5, width 8.1; carapace dark brown with genus-specific Union-Jack pattern and narrow light median and lateral bands ( Fig. 5A View FIGURE 5 ); sternum black; covered with brown setae ( Fig. 5C View FIGURE 5 ).

Eyes ( Fig. 2A View FIGURE 2 ). Diameter of AME: 0.22; ALE: 0.21; PME: 0.66; PLE: 0.65.

Chelicerae. Very dark brown with an elongated patch of golden setae frontally ( Fig. 2A View FIGURE 2 ).

Labium. Dark brown with lighter anterior margin ( Fig. 5C View FIGURE 5 ).

Endites. Dark brown, anteriorly lighter ( Fig. 5C View FIGURE 5 ).

Legs. Uniformly greyish-brown; venter of coxae black ( Fig. 5C View FIGURE 5 ).

Opisthosoma. Length 8.7, width 6.0; dorsally with dark brown cardiac mark that is bordered by dark lateral spots and white lines; transverse white lines and dark spots in posterior half; laterally brown, lighter towards venter ( Fig. 5A View FIGURE 5 ). Venter black with few silvery setae ( Fig. 5C View FIGURE 5 ).

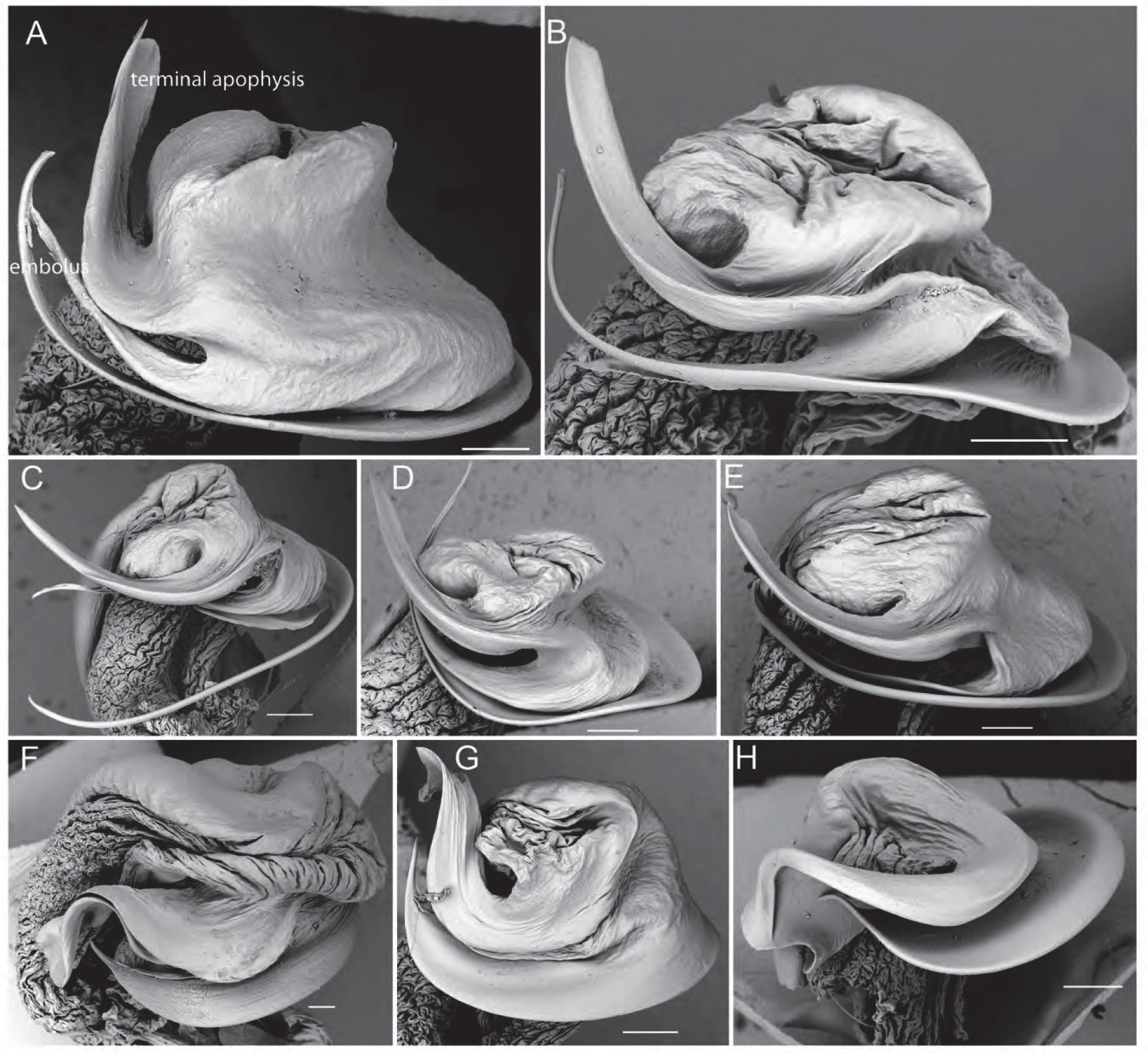

Pedipalps. Cymbium dorsally covered in silvery setae, tip with ca. 3–5 macrosetae ( Figs 2B View FIGURE 2 , 5E–F View FIGURE 5 ); tegular apophysis apically notched, with slightly curved short ridge ( Figs 2C View FIGURE 2 , 5J–K View FIGURE 5 , 6A View FIGURE 6 ); embolus sickle-shaped; terminal apophysis spatulate, slightly curved with flat, broad tip ( Figs 2D View FIGURE 2 , 5I View FIGURE 5 , 7E View FIGURE 7 ).

Female (based on AM KS114583 View Materials ).

Total length 20.9.

Prosoma. Length 10.0, width 6.5; carapace and sternum colouration as male ( Figs 5B, D View FIGURE 5 ).

Eyes. Diameter of AME 0.39, ALE 0.30, PME 0.73, PLE 0.69.

Chelicerae, labium, endites, legs and opisthosoma. Opisthosoma length 10.9, width 8.3; otherwise as male, with overall lighter colouration ( Figs 5B, D View FIGURE 5 ).

Epigyne about as long as wide, medium septum hourglass shaped, i.e. anteriorly as wide as posterior transverse part ( Figs 2E View FIGURE 2 , 5G View FIGURE 5 ); spermathecal heads globular, diameter much larger than diameter of spermathecal stalks ( Figs 2F View FIGURE 2 , 5H View FIGURE 5 ).

Remarks. Tasmanicosa godeffroyi was initially described by Koch (1865), apparently based on a single mature female holotype with eggsac collected in Wollongong, New South Wales. Subsequently, Koch (1877) redescribed the species and listed material from Sydney (New South Wales), Peak Downs (Queensland) and Wollongong, the latter probably referring to the holotype female (all from Museum Godeffroy); from Sydney (in “Bradley’s Collection”; today considered lost (Framenau 2005)); and from 'New Holland' (Kgl. Naturalien Kabinett zu Stuttgart, Museum Stuttgart) (see Renner 1988 for a list of lost types). Subsequent cataloguers apparently considered Koch’s (1877) later listing as syntype series. For example, Rack (1961) catalogued a specimen from Peak Downs as syntype and McKay (1985) followed with listings of syntypes lodged in the NHM and ZMH. However, none of the specimens in these collections examined for this revision was explicitly labelled from Wollongong or represented a female carrying an eggsac as described by Koch (1865) (although this eggsac could have subsequently been lost). Consequently, we consider the holotype female of this species lost. We do not consider it necessary to establish a neotype for this common and easily recognised species, in particular as material is available that was identified by the original author of the species.

Koch (1877: 957) already listed his Lycosa bellatrix as junior synonym of T. godeffroyi : “ Lycosa bellatrix L. Koch ibidem p. 866, altes Weibchen von Lyc. Godeffroyi nach dem Ablegen der Eier” [from German: old female of Lyc. Godeffroyi after laying eggs]. McKay (1985) proposed a specimen labelled Lycosa necatrix (NHM 1919.9.18.1187) as possible holotype; however, this assumption cannot be unequivocally supported although a species-group name Lycosa necatrix was apparently never published by L. Koch from Australia. We therefore consider the holotype of Lycosa bellatrix lost.

Strand (1907) provided the description of a male with morphological similarities to T. godeffroyi , which he potentially considered to represent a new species, Tarentula zualella . His description concludes vaguely (p. 219, from German) “I want to identify this specimen as Tar. Godeffroyi L.K., despite some differences in the arrangement of the eyes […]. Perhaps this new species may receive the new name Tar. zuallela ”. The species was transferred to Allocosa Banks, 1900 by Roewer (1955) and is as such listed in recent catalogues ( World Spider Catalog 2016); however, to our knowledge the subfamily Allocosinae Dondale, 1986 does not occur in Australia (Framenau 2007).

As the holotype is apparently not present at the WNHM ( Jäger 1998) and considering the uncertain diagnosis of the species from T. godeffroyi , we here consider Allocosa zualella a junior synonym of T. godeffroyi , also taking into account the distribution of other Tasmanicosa near Sydney.

Life history and habitat preferences. Following Bill Humphrey’s seminal Ph.D. thesis on this species and resulting publications ( Humphreys 1974, 1975a, b, 1976a, b, 1978), T. godeffroyi is one of the best studied wolf spiders in Australia. In the ACT, it occupies margins of and clearings in sclerophyll forest, with highest densities only in small patches in rough pasture that is reverting to bush. High densities are being maintained in clearings such as under high-voltage transmission lines suggesting it to be a disturbance indicator within natural successional communities ( Humphreys 1976b). Here, spiders construct shallow burrows (4–18 cm deep) often with leaf litter collar and associated with a log or rock or ground crack ( Humphreys 1976b). Similar habitat preferences were reported from Western Australia, where the species occupies dry open woodland and forest with expanses of bare to lightly littered ground, but spiders also invade dry pasture and crops ( Main 1976). Collection data with specimens included a variety of habitat types; such as chenopod scrublands; various eucalypt woodlands such as Black Box ( Eucalyptus largiflorens ), Red River Gum ( E. camaldulensis ), and Poplar Box ( E. populnea ); Callitris woodland, mallee woodland, but also grasslands, including spinifex ( Triodia spp.) and other semi-arid grasslands. Its frequent affinity with agricultural areas (paddocks, Lucerne crops) and other cultivated areas near houses in pools and gardens resulted in the common name ‘garden wolf spider’ for T. godeffroyi .

Near Canberra, females produced eggsacs from November to April with young emerging about a month later ( Humphreys 1976b). Eggsacs averaged about 388 eggs with egg numbers ranging from ca. 200 to 1,000 eggs. Young resulting from the peak reproductive period (January and February) overwinter as immatures and reach the penultimate stage by the following winter. Females and males moult to maturity during or after the second winter, and males die shortly after reproductive activity ( Humphreys 1976b). Females develop through approximately 15 instars. Some long-lived females produce eggs in two consecutive breeding seasons.

Two periods of parasite induced mortality occurred in T. godeffroyi from the ACT; the first in eggs caused by scelionid wasps, and the second in large immatures caused by acrocerid flies ( Humphreys 1976b).

Tasmanicosa godeffroyi shows behavioural thermoregulation of their clutch. Females with eggsacs actively maintain, within constraints, a temperature regime higher than ambient temperature for their eggsac by exposing it to the sun or, when temperature outside falls, keep it in the comparatively and temporarily warmer burrow chamber ( Humphreys 1974).

Bites by Tasmanicosa species, mostly T. godeffroyi , only cause minor effects in humans and itchiness and redness of the bite site are not uncommon ( Isbister & Framenau, 2004). However, venom can be fatal to dogs, cats and other animals that can reportedly be killed within one hour ( Raven & Seeman 2008). Histamine appears to be the major pharmacological component of T. godeffroyi venom ( Rash et al. 1998).

Distribution. Tasmanicosa godeffroyi is found in the southern half of Australia, generally south of 20°S Latitude ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 ).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Tasmanicosa godeffroyi ( L. Koch, 1865 )

| Framenau, Volker W. & Baehr, Barbara C. 2016 |

Tasmanicosa tasmanica

| Roewer 1959: 351 |

Allocosa woodwardi

| Rack 1961: 39 |

| Roewer 1955: 207 |

Allocosa zualella

| Roewer 1955: 207 |

Dingosa tasmanica

| Roewer 1955: 240 |

Geolycosa godeffroyi

| McKay 1973: 380 |

| Rack 1961: 38 |

| Roewer 1955: 243 |

Lycosa zualella

| McKay 1985: 84 |

| McKay 1973: 380 |

| Rainbow 1911: 274 |

Lycosa woodwardi

| Moritz 1992: 329 |

| McKay 1985: 84 |

| McKay 1973: 380 |

| Rainbow 1911: 274 |

| Simon 1909: 182 |

Tarentula godeffroyi

| Strand 1907: 216 |

Tarentula zualella

| Strand 1907: 218 |

Lycosa tasmanica

| McKay 1985: 84 |

| McKay 1973: 380 |

| Hickman 1967: 79 |

| Rainbow 1911: 273 |

| Hogg 1905: 571 |

Lycosa godeffroyi

| Platnick 1993: 487 |

| Moritz 1992: 314 |

| McKay 1985: 77 |

| Main 1964: 120 |

| Rainbow 1917: 488 |

| Rainbow 1911: 268 |

| Hogg 1900: 77 |

| Koch 1877: 957 |

| Koch 1877: 957 |

| Koch 1865: 867 |

| Koch 1865: 866 |