Bairdoppilata cushmani ( Tressler, 1949 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.5175.3.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:44FB9C3D-3188-4BFB-BDB8-C1324729A396 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7008003 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03FE6B50-FFFC-FFB5-ECD6-AD1A6F12188A |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Bairdoppilata cushmani ( Tressler, 1949 ) |

| status |

|

Bairdoppilata cushmani ( Tressler, 1949) View in CoL

( Figures 3 View FIGURE 3 , 4 View FIGURE4 , 5A–J View FIGURE 5 , 6A–L View FIGURE 6 , 7A–N View FIGURE 7 , 8A–P View FIGURE 8 , 9A–S View FIGURE 9 , 10A–G View FIGURE 10 )

1949 Nesidea cushmani Tressler : 342, figs. 4–8.

1961 Bairdoppilata carinata Kornicker : 66, pl. 1, figs. 5a–e; figs. 9A–J, 10B–C, E [junior subjective synonym].

1963 Bairdoppilata triangulata Edwards. —Benson & Coleman, p. 20, pl. 3, figs. 1–3; fig. 9.

? 1966 Bairdoppilata carinata Kornicker. —Baker & Hulings, pl. 2, fig. 12.

1969 Bairdoppilata (Bairdoppilata) cushmani (Tressler) .—Maddocks, p. 68, figs. 34A–G, 35A–C.

1975 Bairdoppilata (Bairdoppilata) cushmani (Tressler) .—Teeter, figs. 3f, 4d.

1977 Bairdia aff. B. amygaloides Brady. —Bold, table 3 [fide Bold, 1988A, p. 152].

1983 Bairdoppilata cushmani (Tressler) .—Palacios-Fest et al., table 1, pl. 1, figs. 3–4.

1988B Bairdoppilata cushmani (Tressler) .—Bold: 154, appendix.

1992 Bairdoppilata cushmani (Tressler) .—Machain-Castillo & Gio-Argaez, appendix 1.

1994 Bairdoppilata cushmani (Tressler) .—Machain-Castillo & Gio-Argaez, table 1

2009 Bairdoppilata cushmani (Tressler) .—Maddocks et al., Checklist, p. 888.

Material Examined: Two living male specimens from the Bahamas. One male carapace with dry body fragments from the Bahamas. One female carapace with dry body fragments from Cuba. One living male and one female from the West Coast of Florida. Numerous empty carapaces and valves from sediment samples collected in carbonate platform environments of the Bahamas, Belize , Cozumel, Cuba, the Florida Keys, Grand Cayman Island , Honduras , and Jamaica.

Dimensions: Specimen 1026F: LVL 1.252 mm, LVH 0.812 mm, RVL 1.225 mm, RVH 0.758 mm. Specimen 1648M: LVL 1.093 mm, LVH 0.624 mm, RVL 1.065 mm, RVH 0.626 mm. Specimen 2395F: LVL 1.089 mm, LVH 0.708 mm, RVL 1.098, RVH 0.745 mm. Specimen 2399M: LVL 1.022 mm, LVH 0.648 mm, RVL 1.005 mm, RVH 0.606 mm. Specimen 3114M: LVL 1.122 mm, LVH 0.698 mm, RVL 1.097 mm, RVH 0.648 mm. Specimen 4081WJ, LVL 0.892 mm, LVH 0.554 mm, RVL 0.884 mm, RVH 0.529 mm. Specimen 4082WJ, LVL 0.662 mm, LVH 0.420, RVL 0.653 mm, RVH 0.396 mm. See also Figs. 3 View FIGURE 3 , 4 View FIGURE4 .

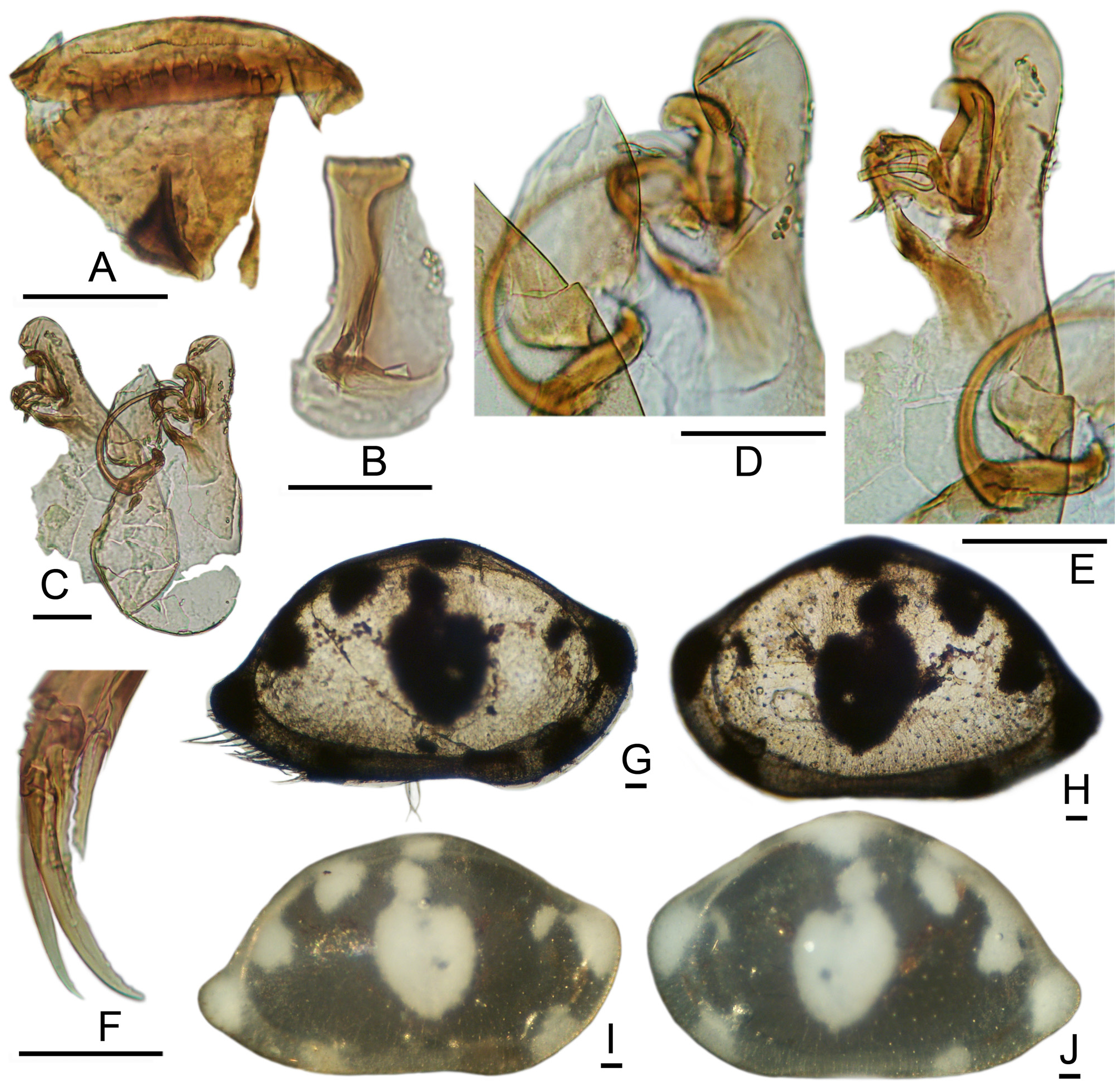

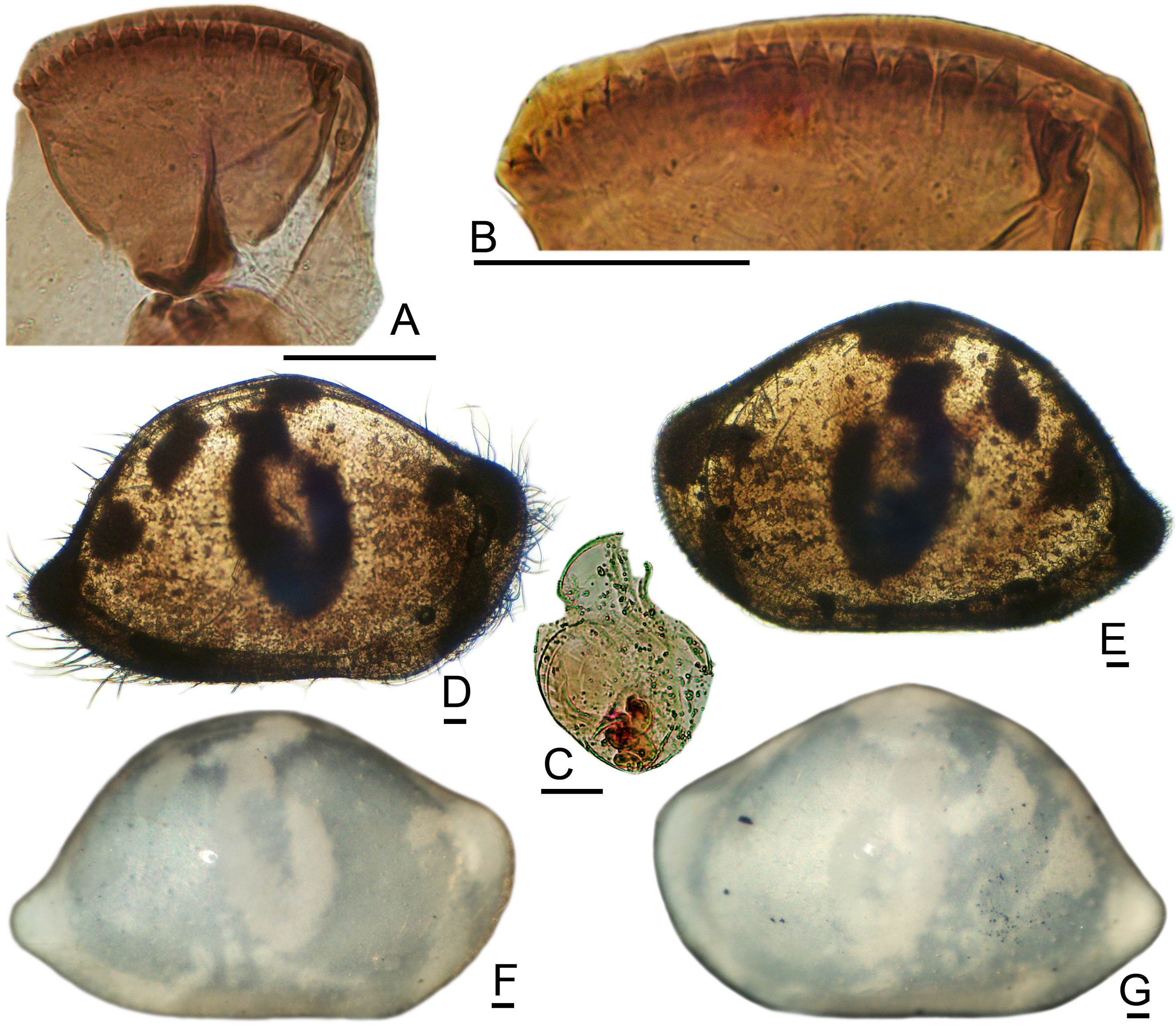

Esophageal Valve: The plate is broad, pie-shaped, with a gently curved posterior margin, about 12 small conical teeth of equal sizes, and multilobate corner teeth ( Figs. 5A View FIGURE 5 ; 6C–E View FIGURE 6 ; 8G–H View FIGURE 8 ; 9A View FIGURE 9 ; 10A–B View FIGURE 10 ). [One deviant specimen (2399M) has two teeth in near-central position that are longer and broader than the others ( Fig. 9A View FIGURE 9 ). In all other specimens, including 2395F from the same locality, the plate has numerous small conical teeth of uniform size. The plate is tiny and cannot be oriented consistently for viewing, so that some uncertainty is associated with these generalizations.] The chevron groove is broad with parallel brush setules, giving a striate texture in transmitted light. The scroll is deeply incised with a hemicircular excavation and triangular spine.

Anatomical Remarks: The carapace surface is glassy-smooth, with visible NPC but no puncta. It is transparent in live specimens, becoming translucent or cloudy in subfossil material. The lateral outline of the left valve is high-arched, subtriangular to subpentagonal, and subtly angulate; with well-marked anterodorsal and anterior angles, indistinct or rounded posterodorsal angle, a caudal process that is only slightly sinuous, diagonally truncate anteroventral and posteroventral margins, and nearly horizontal ventral margin.

The patch pattern is diagnostic and well expressed in both adults and instars ( Figs. 5G–J View FIGURE 5 , 7E–N View FIGURE 7 , 8I–L View FIGURE 8 , 9J–M View FIGURE 9 , 10D–G View FIGURE 10 ). A shield-shaped to ovate central patch may be indented dorsally, becoming more or less U-shaped. Above this, and sometimes partly connected to it, are two small opaque patches located beneath the mid-dorsal angle. In the posterodorsal region are two larger patches, the upper of which is circular or irregular, and the lower of which is wedge-shaped or triangular. Another spot is located at the anterodorsal angle, which usually has a smaller anterior spot attached by a peninsula. Additional opaque regions with indistinct contours are located at the caudal angle, anteroventral, and posteroventral margins.

The two opaque spots of the patch pattern along the posterodorsal slope are distinctive. In well-conserved subfossil assemblages, adult and juvenile valves of B. cushmani are easily recognized and may be quickly sorted by looking for the two posterodorsal spots. This is convenient, because at least two other smooth species are common in the central Caribbean but have only a single posterodorsal spot. For quick assignment of isolated individuals of B. cushmani in subfossil assemblages, the most reliable landmark is the two posterodorsal opaque spots.

Taxonomic Remarks: On the H:L plots ( Figs. 3–4 View FIGURE 3 View FIGURE4 ) the conspicuous length of the adult clusters is due to sexual dimorphism, with females being longer than males and also a little higher in proportion to length. Within these clusters, there is some tendency for separation of local geographic populations, although with considerable overlap. The Florida population appears to be shorter and higher relative to length. The Bahamas population is longer, but relatively lower. The population from Roatan, Honduras is both longer and relatively higher. The largest individuals, which have intermediate H:L proportions, are from Cuba. Formal taxonomic interpretation of this heterogeneity, perhaps as a superspecies with component species or subspecific entities, will require more evidence, especially more comprehensive documentation of soft anatomy and ontogeny from other locations.

Geographic Distribution: This species is widely distributed in carbonate platform environments through the Caribbean, including the northern “transition zone” of Bold (1977). It is abundant in many subfossil assemblages, and it is usually the most common species of Bairdoppilata .

Kornicker (1961) collected it from bioclastic sand and rock surfaces with thin sand cover of Bimini. Teeter (1975) reported it in the carbonate-platform biofacies of Belize. Additionally, it has been reported from both the eastern and western parts of the Yucatan platform ( Machain-Castillo & Gio-Argaez 1992, Palacios-Fest 1983). Bold (1988A, Table 2 View TABLE 2 ) summarized its distribution as including the Gulf of Mexico, Alacran reef on the northwestern Yucatan platform, Cozumel on the northeastern Yucatan shelf, the Belize platform, and the Caribbean, but not the Nicaragua shelf. Fithian (1980, unpublished) stated that it is one of the most abundant species on the Paria-TrinidadOrinoco Shelf.

In the material at hand it has been identified in near-reef and platform sediments from the Bahamas, Belize, Cozumel, Cuba, Florida Bay and the Florida Keys, Grand Cayman Island, Jamaica, and Roatan Island, Honduras. It has not been seen or reported in assemblages of the Bermuda Platform, the Flower Gardens in the northern Gulf of Mexico, the reefs near Vera Cruz in the western Gulf of Mexico, and the Gulf of Campeche in the southern Gulf of Mexico.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |