Halistemma rubrum (Vogt, 1852)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3897.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CB622998-E483-4046-A40E-DBE22B001DFD |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03FC87BC-FFCC-FFEC-FF62-ABB666E2FE79 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Halistemma rubrum (Vogt, 1852) |

| status |

|

Halistemma rubrum (Vogt, 1852) View in CoL

Agalma rubra Vogt, 1852a, p. 522 View in CoL , Pl. XIV, figs. 4–5 & 8; 1852b, p. 273, Pl. 5, figs. 10–11, 14; 1854, pp. 62–82, Pls. VII–XI; Sars, 1859, p. 8; Spagnolini, 1869, pp. 631–632;

Agalmopsis punctata Kölliker, 1853, pp. 15–18 , Pl. IV; Leuckart, 1853, pp. 1–95, Pl. I, figs. 1,19–20, Pl. II, figs. 1–2, 5–7.

Agalmopsis rubra Leuckart, 1853, pp. 1–95 , Pl. I, figs. 5–7, 11, Pl. II, figs, 18–19; Schneider, 1898, p. 123; 1899, pp. 41–48, figs. 34–42; 1900, p. 17, figs. 2, 5–15, 30–37, 46–50, 52, 54–71, 75, 80–94, 159–164, 196, 232;

Agalma rubrum Leuckart, 1854, pp. 321–331 , Pl. XII; Claus, 1860, figs. 8,28, 32, 35, 39; Keferstein & Ehlers, 1860, p. 261; 1861, pp. 25–26, Pl. I, figs. 14–15, Pl. II, fig. 5; Weissmann, 1883, p. 209–211, Pl. XXII; Delage & Hérouard, 1901, fig. 376.

Halistemma rubrum Huxley, 1859, pp. 129–130 View in CoL , pl. XII, fig. 9; L. Agassiz, 1862, p. 369; Metschnikoff, 1874, p. 57–61, Pl. X, Pl. XI, fig. 1; Fewkes, 1880, Pl. II, figs. 3–4; Bedot, 1896, p. 407; Lo Bianco, 1904, fig. 149; Totton, 1965, pp. 56–59, Pl. XII; D. Carré, 1971, p. 77–93, figs. 1–9, Pls. I–III; Daniel, 1974, p. 45–47, text–fig. 3E–G; 1985, p. 71–75, fig. 15a–f; Kirkpatrick & Pugh, 1984, p. 34, fig. 8; Gili, 1986, pp. 273–274, figs. 4.48a, 4.64a–d; Pugh & Youngbluth, 1988, fig. 6D; Gasca, 1990, p. 48, Pl. I, fig. 4; Pagès & Gili, 1992, p. 73, fig. 9; Carré & Carré 1995, figs. 165A, 177A,C, 181F, 189; Pugh, 1999a, p. 482, figs. 3.11, 3.22; Gao et al., 2002, p. 71, fig. 27; Bouillon et al., 2004, p. 211, fig. 123C–G; 2006, figs. 208 I–J, 209A–B; Araujo, 2006, p. 58, Pl. VI, fig. 12.

Agalma punctatum Graeffe, 1860, p. 14 .

Agalma minimum Graeffe, 1860, pp.15–20 View in CoL , Pls. II, III; Haeckel, 1869, p. 46; 1888b, p. 233.

Halistemma punctatum L. Agassiz, 1862, p. 369 View in CoL ; Haeckel, 1888b, p. 367

Stephanomia rubra Bigelow, 1911, p. 284 ; 1918, pp. 426–426, Pl. 8, fig. 5; Leloup, 1935, p. 3; Daniel & Daniel, 1963, p. 194, fig. II 9; Alvariño, 1981, p. 394, fig. 174–4; Totton, 1954, pp. 47–52, text–figs. 12–13 [in partim. non text–figs. 15–18];

Halistemma rubra Totton & Fraser, 1955, p. 3 View in CoL , fig. 4; Trégouboff & Rose, 1957, p. 351, Pl. 77, figs. 6–8, Pl. 78, figs. 1–2; Stepanjants, 1967, pp. 128–129, figs. 71–72; Carré, 1974, p. 211, Pl. III, fig. 1;

?non Halistemma rubrum Zhang, 2005, pp. 22–24 View in CoL , figs. 2D, 18

The above list refers only to important taxonomic changes or to papers that, in some way, describe the species Halistemma rubrum .

Diagnosis. Basic Halistemma ridge pattern on nectophores, with all pairs of ridges incomplete. Two types of adult bract. Tentilla with very small, almost vestigial involucrum and no terminal cupulate process.

Material examined. Five specimens collected by the Johnson-Sea-Link ( JSL) submersibles, including 1 Nectalia stage (*); four from the Bahamas and one from the Gulf of Maine , and three specimens collected by the ROV Doc Ricketts (DR) in the southern part of the Gulf of California, Mexico .

JSL II Dive 973-D4 * 21 October1984 26°17.5'N, 77°43.7'W depth 506 m. GoogleMaps JSL II Dive 1401-D5 30 August1986 39°51.7'N, 70°22.6'W depth 640 m. GoogleMaps JSL II Dive 1683-D1 9 October1988 26°27.0'N, 77°57.4'W depth 445 m. GoogleMaps JSL I Dive 2656-D3 17 November1989 26°4.3'N, 77°34.3'W depth 536 m. GoogleMaps JSL I Dive 2656-D6 17 November 1989 26°4.3'N, 77°34.3'W depth 527 m. GoogleMaps DR Dive 335-D5 18 February 2012 24°12.7'N, 109°38.4W depth 245 m. DR Dive 339-D12 21 February 2012 23°33.5'N, 106°47.0'W depth 213 m. DR Dive 344-D10 26 February 2012 24°30.3'N, 108°14.5'W depth 297 m.

Thanks to the kindness of Susan Svonthun, from the Video Laboratory at MBARI, a brief video of the specimen of Halistemma rubrum collected at 245 m during Doc Ricketts Dive 335 will be placed on the website www.youtube.com/user/MBARIvideo.

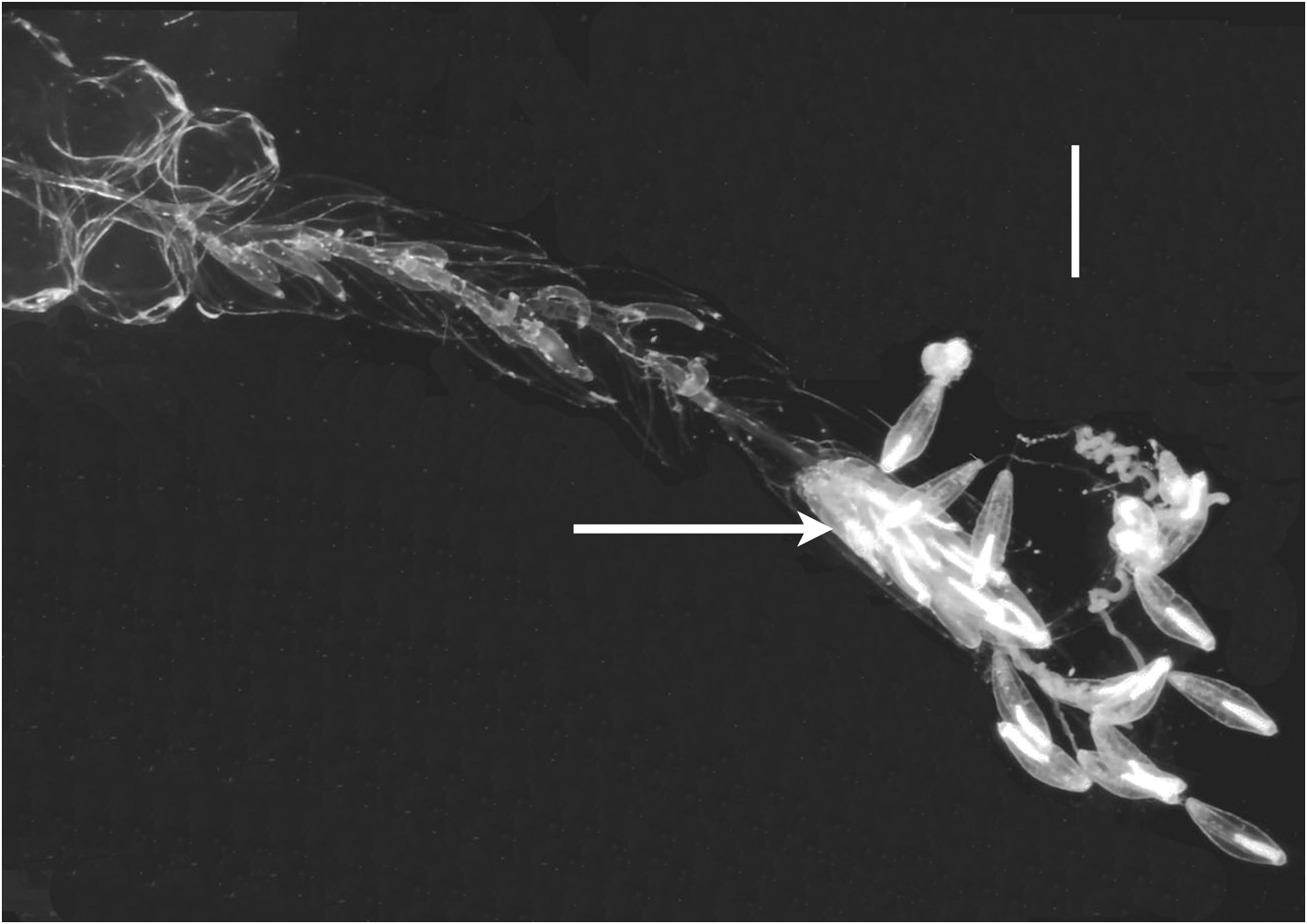

Description: A picture of a specimen collected by the submersible Johnson-Sea-Link I is shown in Figure 11 View FIGURE 11 .

Pneumatophore: The exploded pneumatophore measured approximately 1.0 mm in length and 0.75 mm in diameter, and showed no obvious characteristics or pigmentation.

Nectosome: The nectophores were budded off on the dorsal side of the stem.

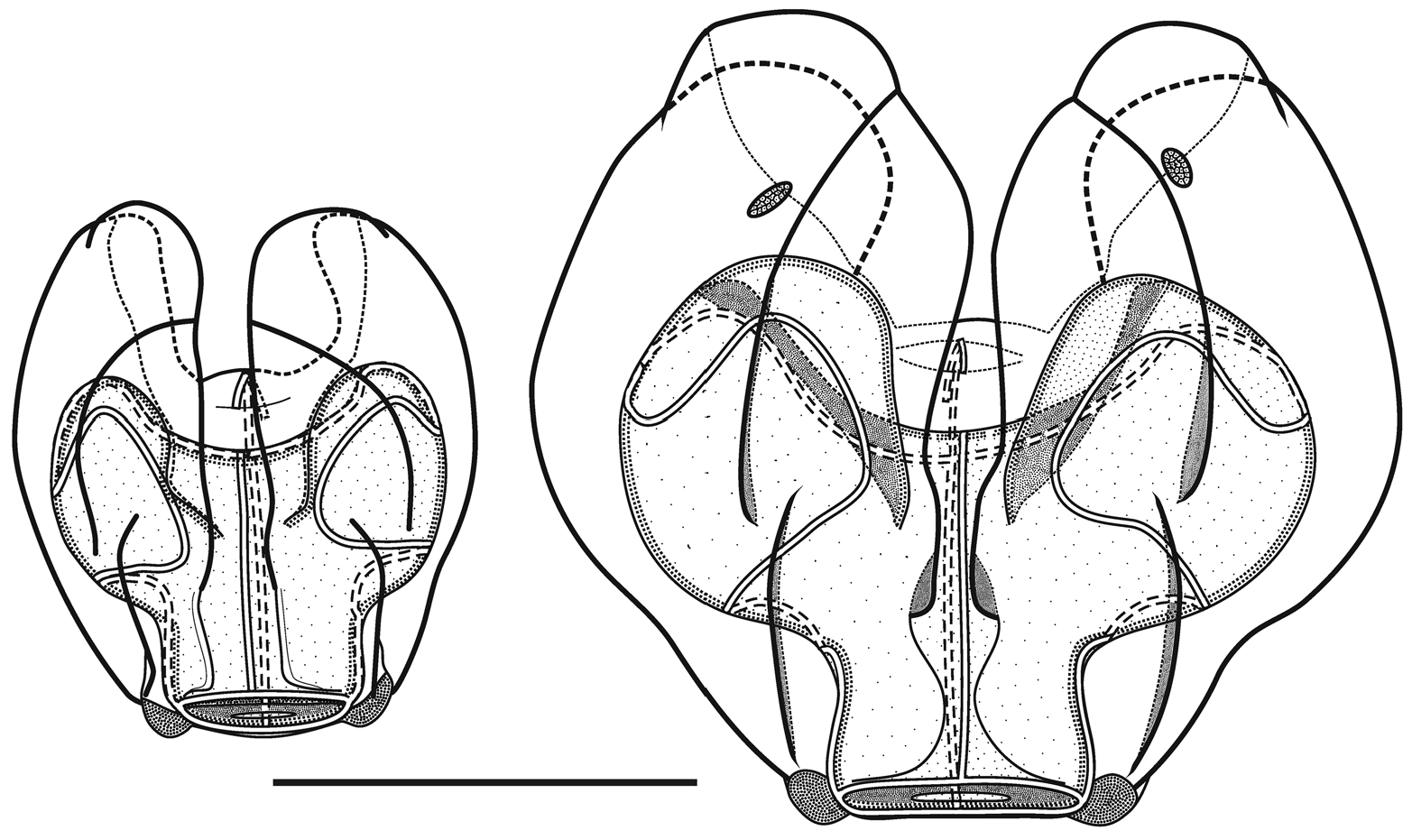

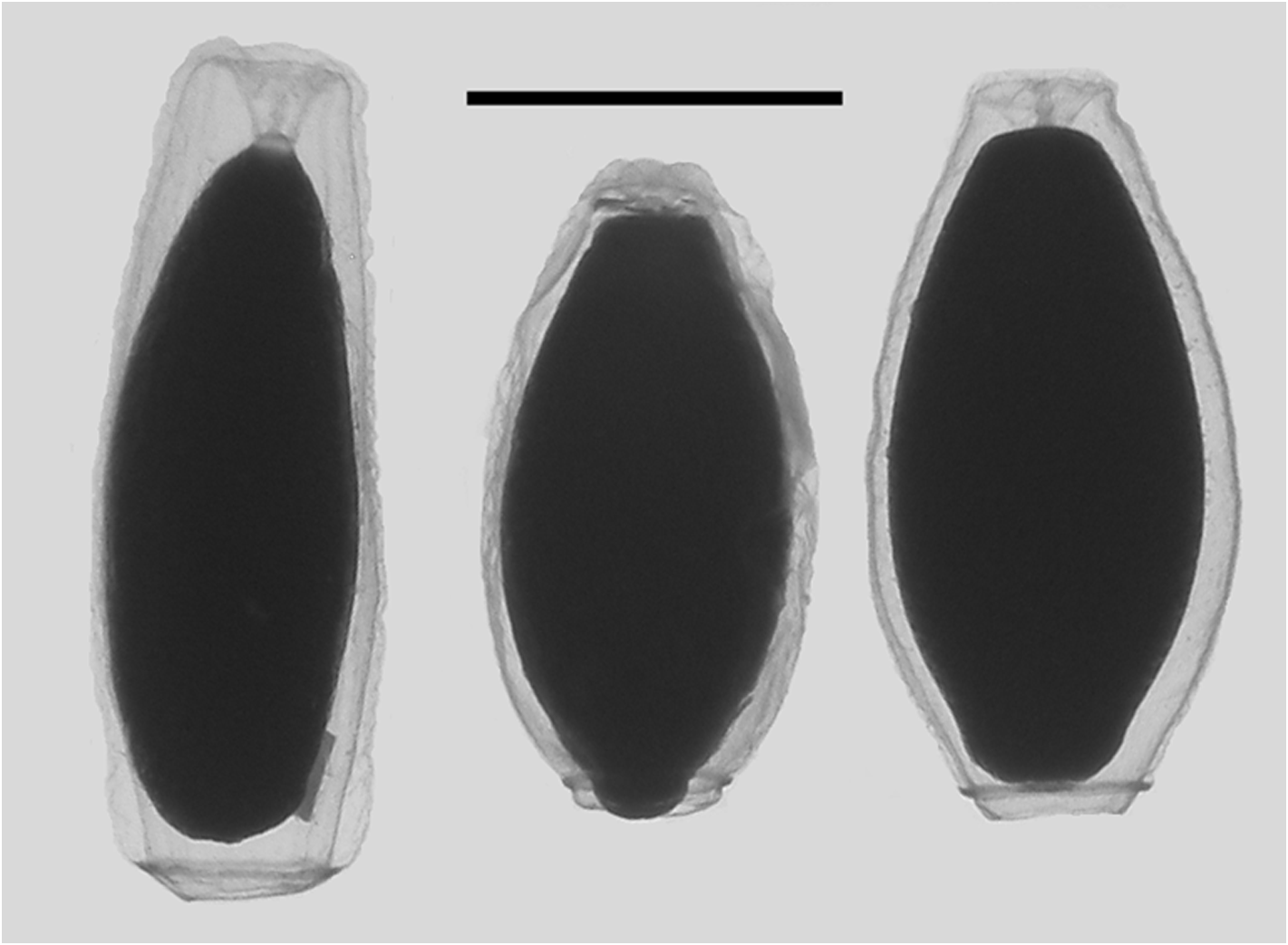

Nectophores: Thirty detached nectophores were present in association with the largest specimen, from JSL II Dive 1401, together with four attached nectophores and nectophoral buds at varying stages of development. Detached nectophores from the JSL II 1401 - D5 and JSL II 2656 -D 6 specimens were quite variable in shape (see Figures 13–15 View FIGURE 13 View FIGURE 14 View FIGURE 15 ) and ranged in size from 1.9 x 1.9 mm (length x width) to 7 x 7 mm .

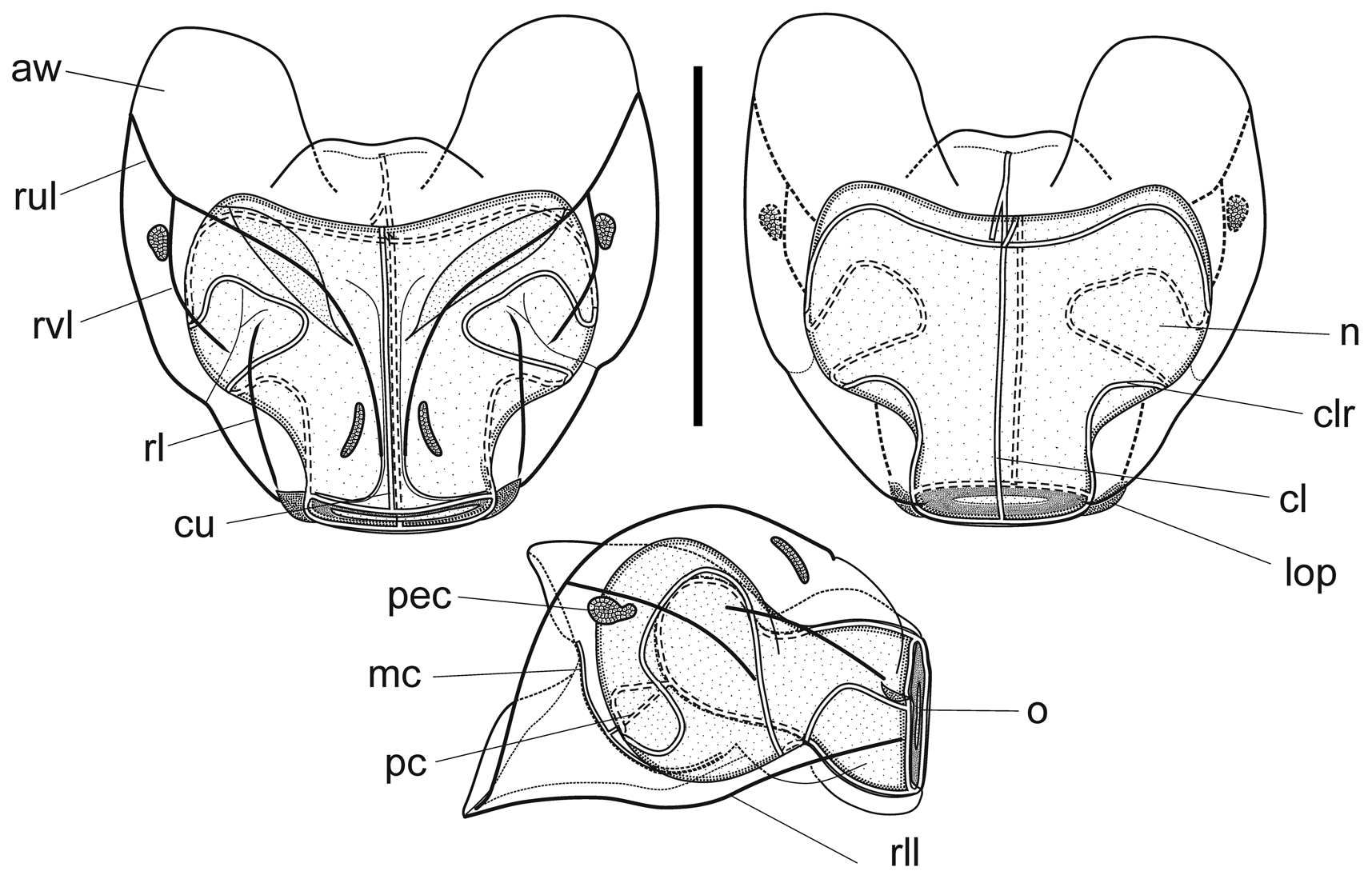

The very young nectophoral bud ( Figure 12 View FIGURE 12 ) clearly showed the pattern of the ridges, with the upper lateral ones bending out, laterally, as they approached the ostium. The relatively large lateral ostial processes were packed with nematocysts, which were also found across the upper margin of the ostium.

In the smaller, younger nectophores ( Figure 13 View FIGURE 13 ) the central thrust block was very flat and undeveloped so that the relatively large axial wings extended well beyond it. For most of their length the upper lateral ridges remained close to the median line of the nectophore. They were very pronounced down to the level where the nectosac began to narrow and, in the slightly older nectophore ( Figure 13 View FIGURE 13 right); here they formed a distinct flap. They then continued on toward the ostium as only a slightly raised line on the surface of the nectophore, before curving out laterally and petering out close to the lateral margins of the nectosac. The lateral and vertical lateral ridges also formed distinct flaps overhanging the surface of the nectophore. Some, but not all, of the preserved younger nectophores bore a pair of ectodermal cell patches, which lay close to the vertical lateral ridges, but they were very delicate and easily abraded. In addition, nematocysts were still found on the lateral ostial processes, as well as across the upper side of the ostium, of the younger nectophore but they had all but disappeared in the slightly larger ones.

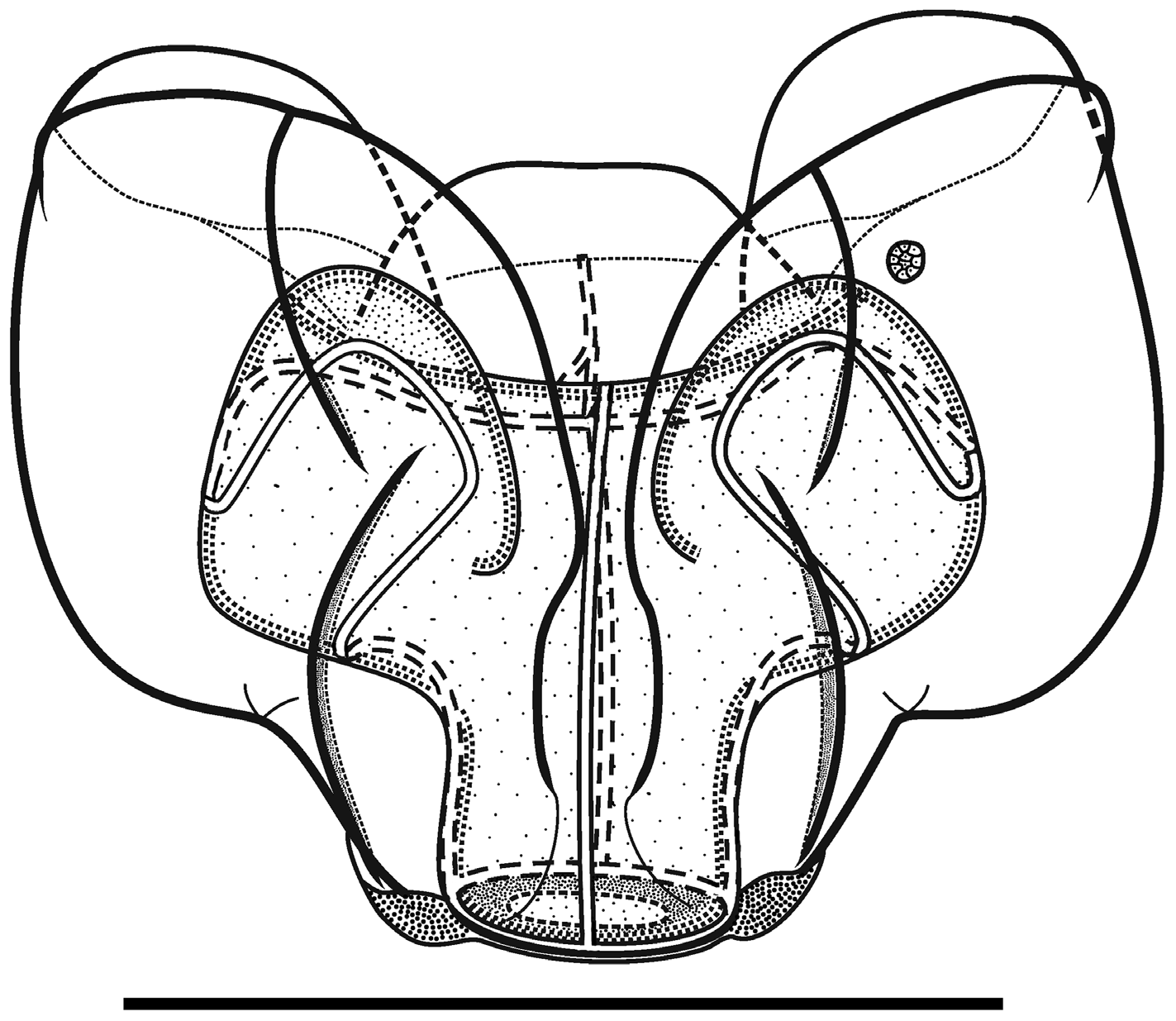

As the nectophores increased in size the central thrust block enlarged and became prominent, although never reaching the level of the apices of the axial wings ( Figures 14–15 View FIGURE 14 View FIGURE 15 ). In the ostial region, a basal mouth plate was absent (even in the younger nectophores). The now relatively small lateral ostial processes, present on either side of the ostium, were covered in small plate-like cells that originally, presumably, lay below the nematocysts, which had been lost by abrasion or usage. There were two pairs of ectodermal cell patches on the upper lateral sides of the nectophore, although some or all of these had been abraded on most nectophores. When present, one pair lay between the lower laterals and the vertical laterals, close to the latter; and the other lay between the upper lateral and lateral ridges, close to the former ( Figure 14 View FIGURE 14 ).

Although the pattern of the ridges on the nectophores of Halistemma rubrum conformed to the basic Halistemma arrangement, as described by Totton (1954) and Pugh & Youngbluth (1988), uniquely the pairs of upper laterals, lower laterals and laterals were incomplete at both ends, while the vertical-laterals were incomplete at their lower end and, indeed, their connection with the upper laterals at times was very vague. The upper lateral ridges ran across the upper surface of the nectophore from the apical margins (though never joining the lower laterals) of the axial wings down towards the ostium. However, the upper laterals were only prominent proximally and, at approximately one sixth of the length of the nectophore away from the ostium, they were reduced to slight prominences on the surface of the nectophore. They continued toward the ostium but, just before reaching it, they curved out and ran parallel to the upper margin of the ostium before petering out. The lateral ridges started on the upper surface of the nectophore, slightly proximal to the distal end of the vertical lateral ridges, and curved outwards slightly as they ran down towards the ostium, petering out just above the lateral ostial processes.

The vertical lateral ridges arose relatively high up the upper lateral ridges, at the level of the apex of the nectosac or above depending on the stage of development. These ridges curved down the lateral surfaces of the nectophore and petered out just distal to the proximal end of the lateral ridges. A strong fold was present in the mesogloea at the distal end of the vertical lateral ridges and the proximal end of the lateral ridges so that these ridges appeared to continue and end in a hook-shaped flap on some nectophores. The lower lateral ridges ran along the entire length of the lower lateral edge of the nectophore from the outer margins of the axial wings to almost the level of the ostium where they petered out and joined the lower margins of the nectophore. There were no distinct ridges on the lower surface of the nectophore. However, in their preserved state, folds ran down the inner apices of the axial wings to just above the level of the nectosac.

The mantle canal, on the lower median surface of the nectophore, ran from a quarter to a halfway down the central thrust block to just below the central apex of the nectosac. The ascending and descending branches were almost equal in length, so that the pedicular canal arose at its mid-point and extended down to the nectosac, where it gave rise to all four radial canals. The courses of the upper and lower canals were straight. The lateral radial canals extended outwards on a smooth curve following the apical surface of the nectosac. At the lateral margins of the nectosac, they first looped downwards and then upwards, looping onto the upper side of the nectosac. They then ran obliquely down the lateral surface of the nectosac and made a short loop onto the lower surface before returning to the mid height of the nectosac and then running directly to join the ostial ring canal.

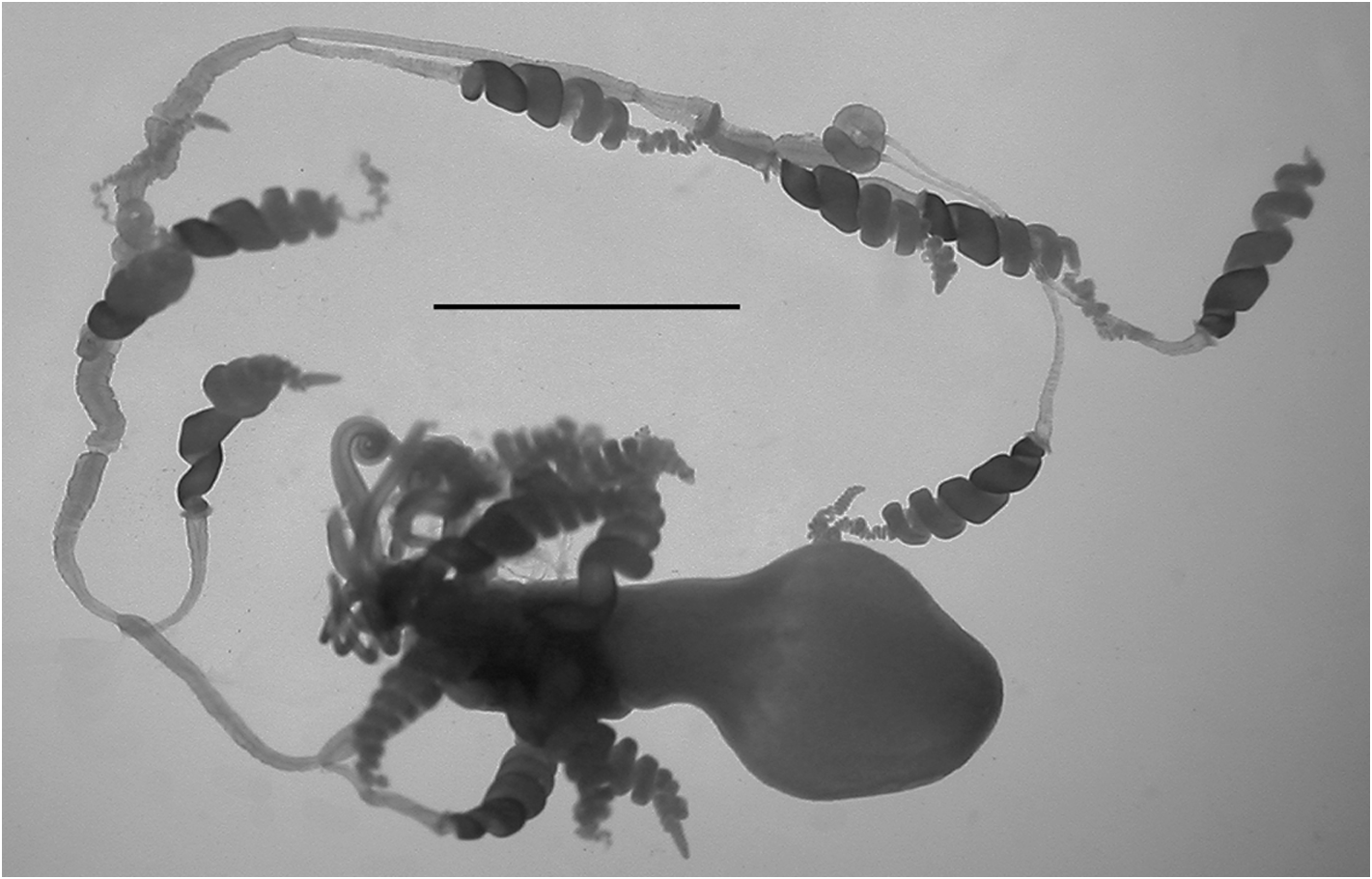

Siphosome: The long siphosomal stem was clearly divided into cormidia that, from the anterior end, consisted of a cluster of palpons; male gonophores individually attached to the stem and interspersed with palpons; a further cluster of palpons; a distinct female gonodendron, with the gonophores borne on a thickened stalk; another cluster of palpons; and finally the gastrozooid, with its tentacle bearing tentilla. The exact disposition of the bracts was not determined.

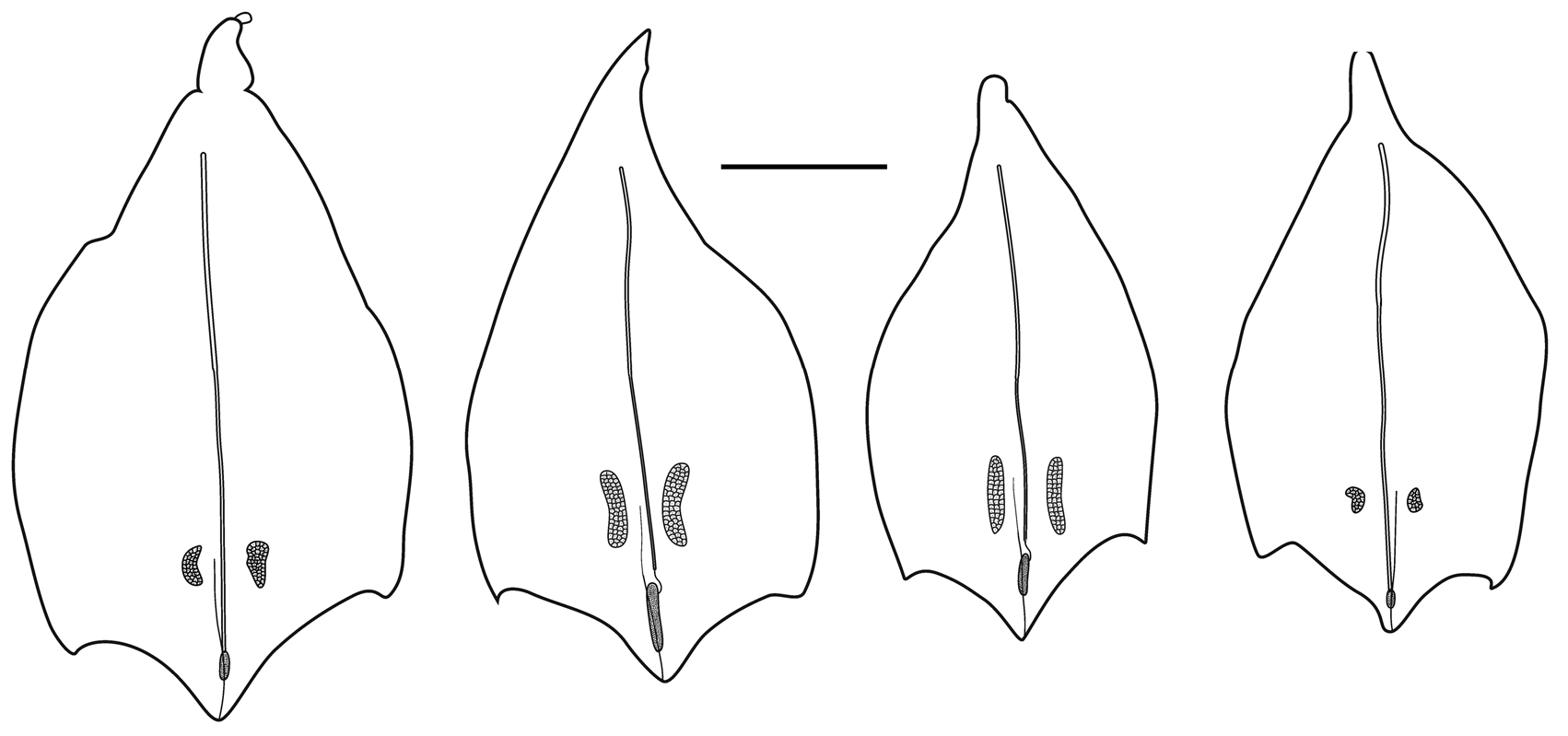

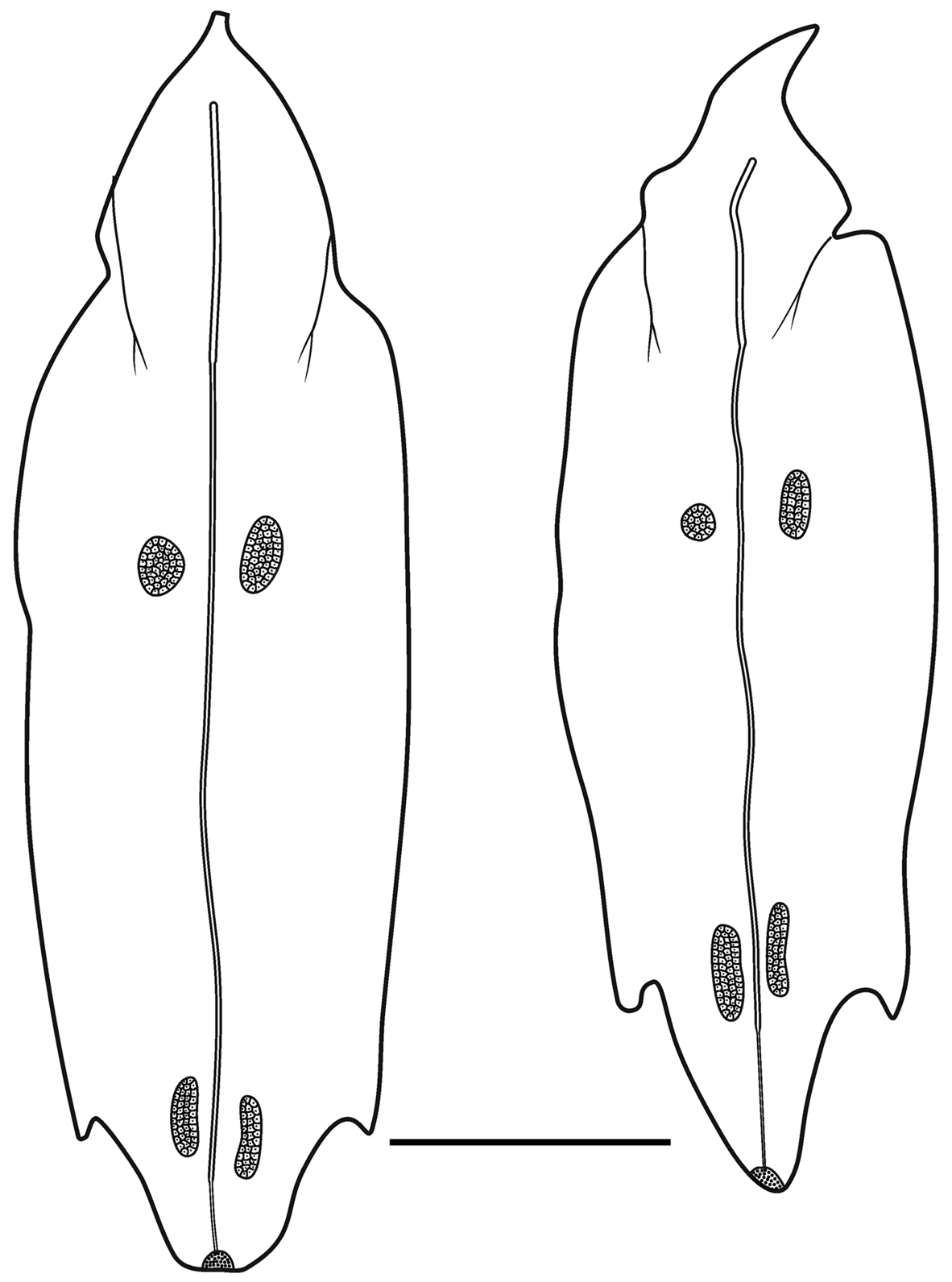

Bracts: There were two types of adult bracts, which were quite flimsy, foliaceous and occurred in enantiomorphic pairs. For the largest specimen, from JSL Dive 1401-D5, the Type A bracts were approximately six times as abundant as the Type B ones, but their arrangement on the stem could not be discerned, although it was thought that the Type A bracts may be inserted laterally, and the Type B ones dorsally .

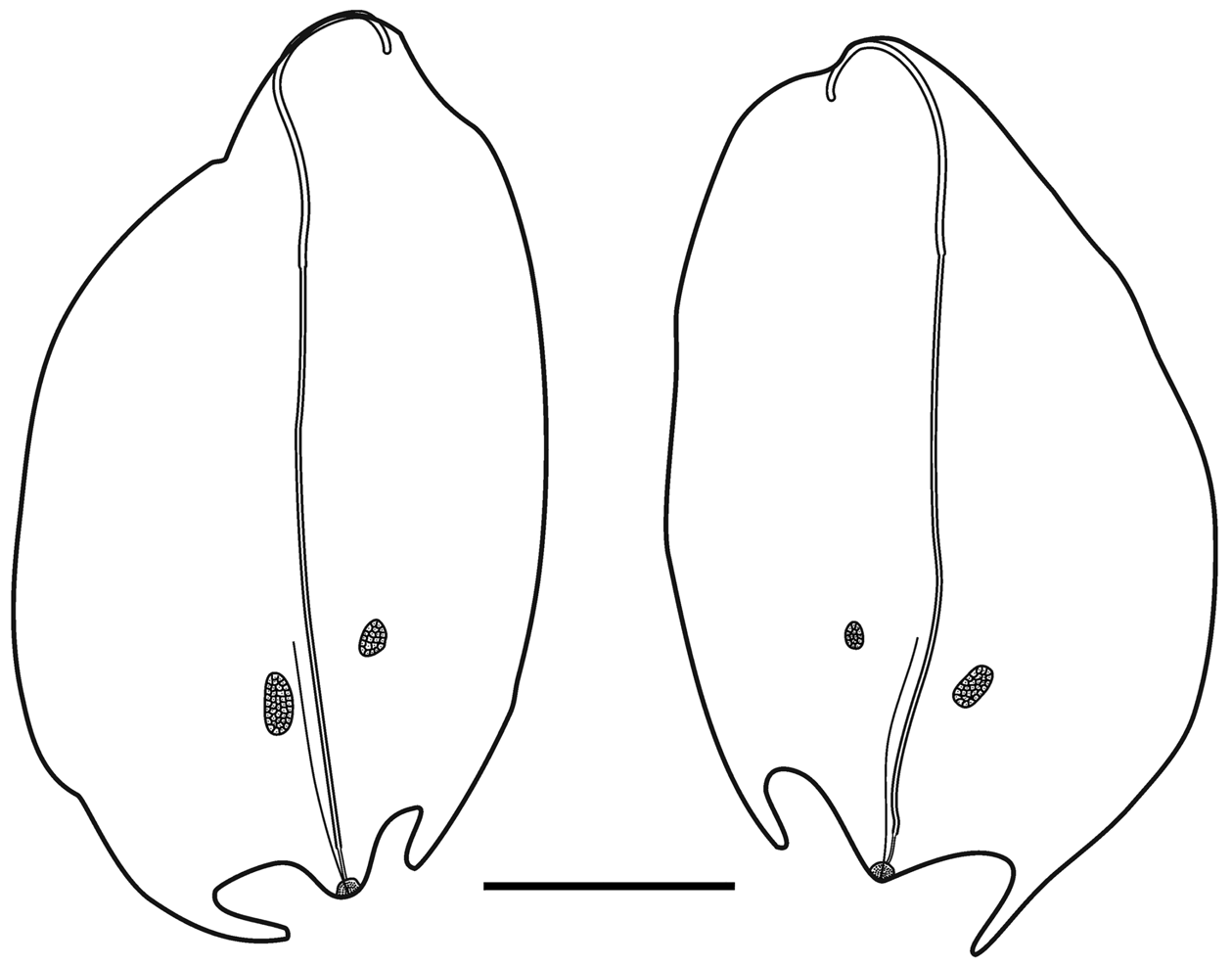

Type A —These bracts were quite variable in shape and measured up to c. 9 mm in length ( Figure 16 View FIGURE 16 ). Several were shorter and squatter, and in the younger ones the bracteal canal tended to extend further toward the proximal end. The distal end was pointed and there was a pair of, asymmetrically positioned, lateral teeth, of variable size, somewhat proximal to it. The tooth on the inner side was more proximal to the one on the outer side. There was a pair of patches of ectodermal cells on the upper surface, whose size and position could vary quite considerably. Often, these were extremely difficult to see, but they were assumed to be sites of bioluminescence. A short median ridge ran proximally from the distal point to peter out between the pair of ectodermal cell patches.

The bracteal canal originated at a variable distance from the proximal end of the bract. It was thicker in its proximal half, where the bracteal attachment lamella was, and thinner distally. As it approached the distal end of the bract it penetrated into the mesogloea, thinning further, and curved upwards to end somewhat distal to the proximal end of a patch of cells, on the upper surface. Although variable in shape, for the most part these patches were elongate structures ( Figure 16 View FIGURE 16 ), but they never extended as far as the median distal tip of the bract itself. They were comprised of numerous nematocysts, which probably were the same as the microbasic euryteles that Carré (1971) identified on the larval bracts (see below), and other types of cell. These were the bracts that Totton (1954, Text—figs 13–14) illustrated. However, on some bracts these nematocyst patches were less elongate, ending some distance before the distal end of the bract ( Figure 16 View FIGURE 16 ).

Type B —These bracts ( Figure 17 View FIGURE 17 ) were of a similar size to the first type but they had more pronounced lateral teeth that extended beyond the median distal point of the bract and they were more oval in shape. Again the tooth on the inner side was more proximal than the one on the outer side. Two patches of ectodermal cells were present on the upper side of the bract, with the patch on the inner side being noticeably proximal to the other one. Another clear distinguishing feature was the arrangement of the bracteal canal. At the proximal end the canal arose on to the upper side of the bract before curving over onto the lower side and thinning at approximately one third of the way towards the distal end. The canal continued for almost the entire length of the bract before slightly narrowing again and penetrating into the mesogloea to end below a small distal cap-shaped indentation, which also contained the same sort of nematocysts as seen on the Type A bracts.

Gastrozooid and tentacle: The gastrozooids ( Figure 18 View FIGURE 18 ) were variable in size, with a relatively small basigaster, but otherwise showed no other remarkable features. They were generally colourless or with a faint orange hue.

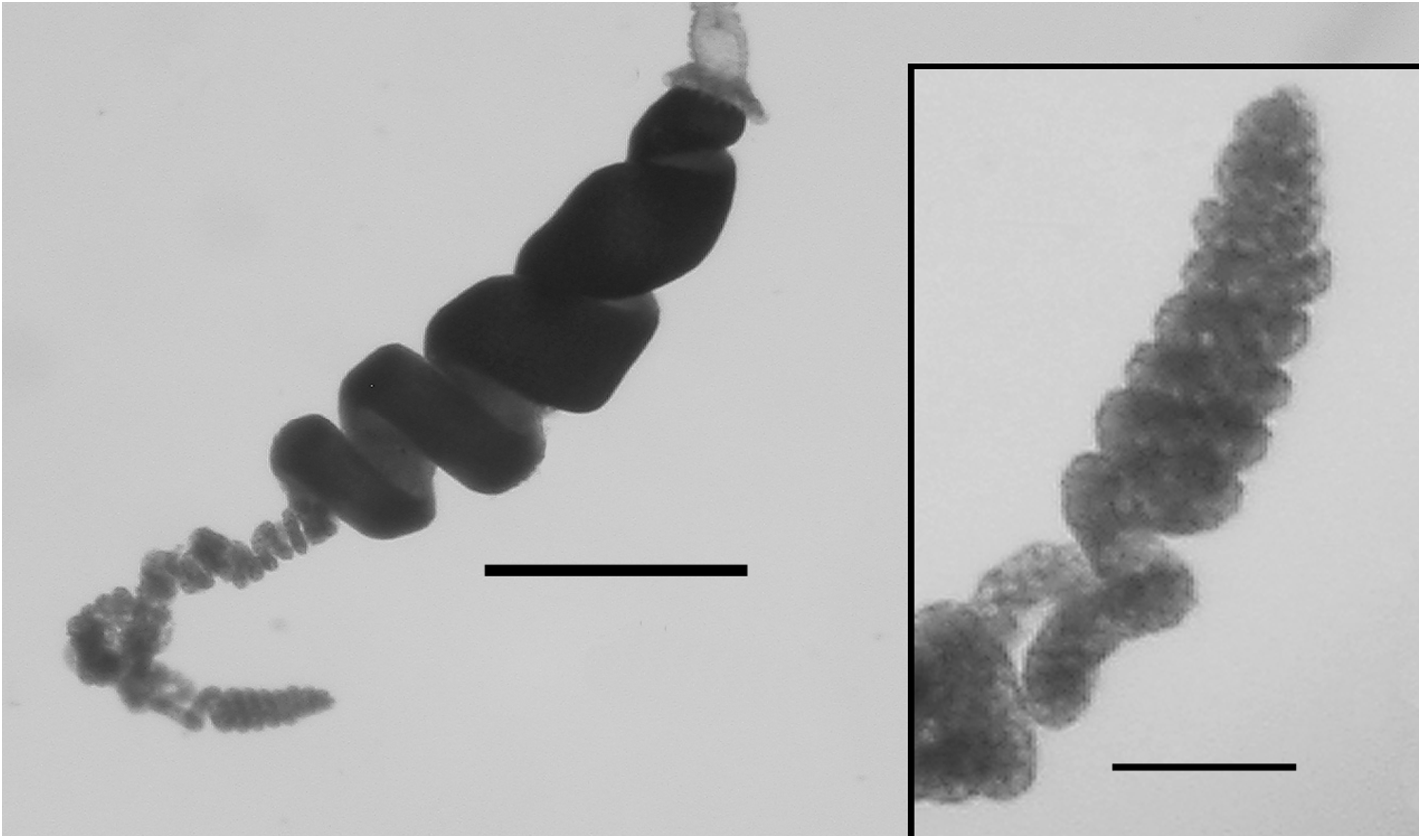

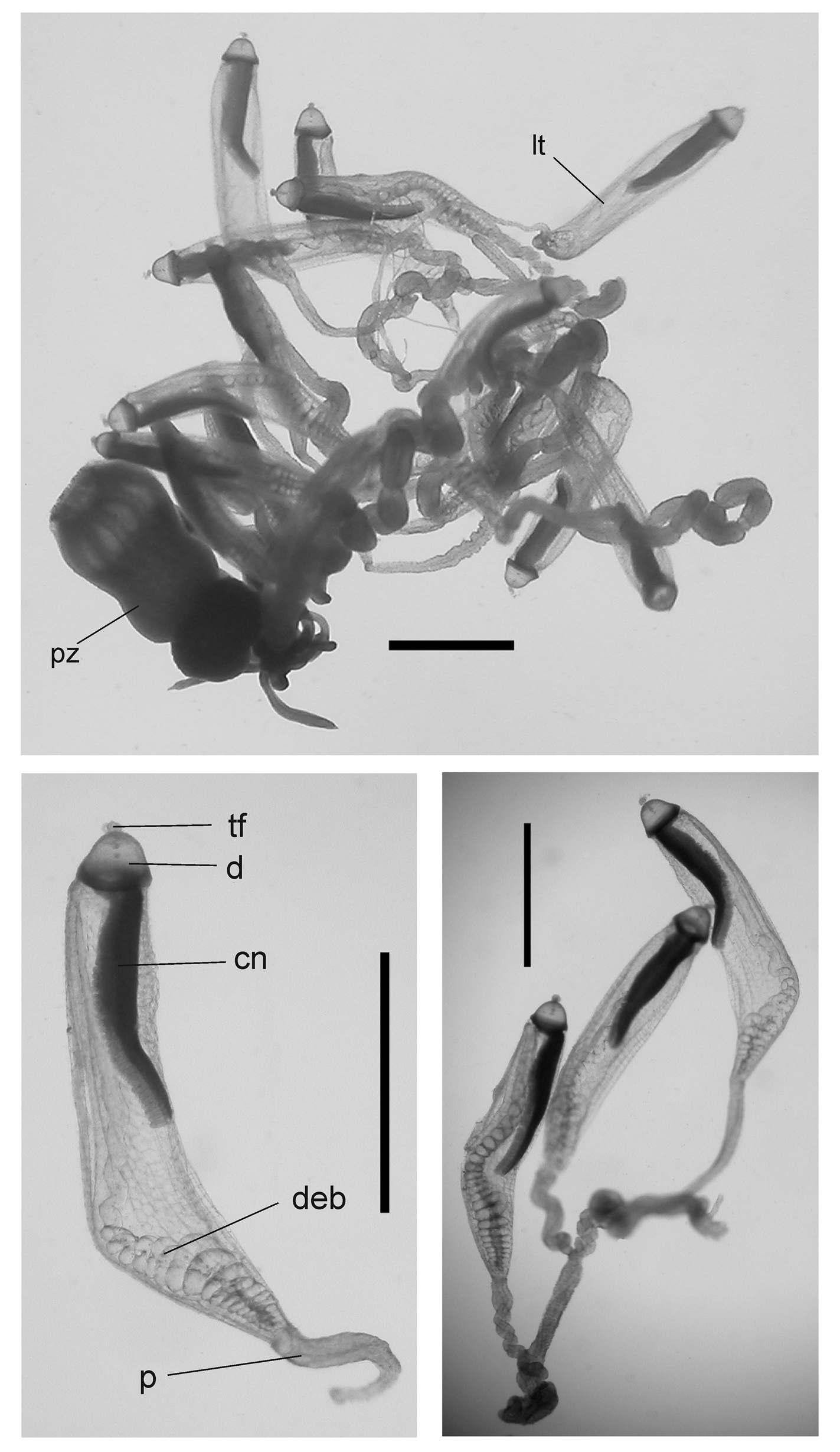

Tentilla: A mature tentillum is shown in Figure 19 View FIGURE 19 . The highly extensile pedicel ended in a very small, almost vestigial involucrum, which did not cover even the most proximal part of the cnidoband. The latter consisted of up to eight spiral coils, although 5–6 was more common. Two types of nematocyst were present on the cnidoband; stenoteles and, probably, anisorhizas. Only 40–50 stenoteles, which measured c. 56 µm in length and 17 µm in diameter, were found in a single row on either side of the proximal part of the first spiral of the cnidoband. The anisorhizas that occupied the remainder of the cnidoband, along with numerous darkly-staining platelets, measured c. 50 µm in length and 8 µm in diameter. The terminal filament contained two types of nematocysts, which were presumed to be acrophores and desmonemes, measuring c. 10 x 13 and c. 14 x 8 µm, as those types have been found on the terminal filaments of other agalmatid species (Purcell. 1984). The loosely and irregularly coiled terminal filament did not end in a cupulate process, but with a tightly coiled tapering section ( Figure 19 View FIGURE 19 , detail).

Palpons: The thin-walled palpons ( Figure 20) were generally featureless, but with a quite marked distal teatshaped proboscis and a narrow peduncle. They measured up to 5.5 mm in length. Each had a long, narrow palpacle attached at its base, but no nematocysts were found on it or on the palpon itself.

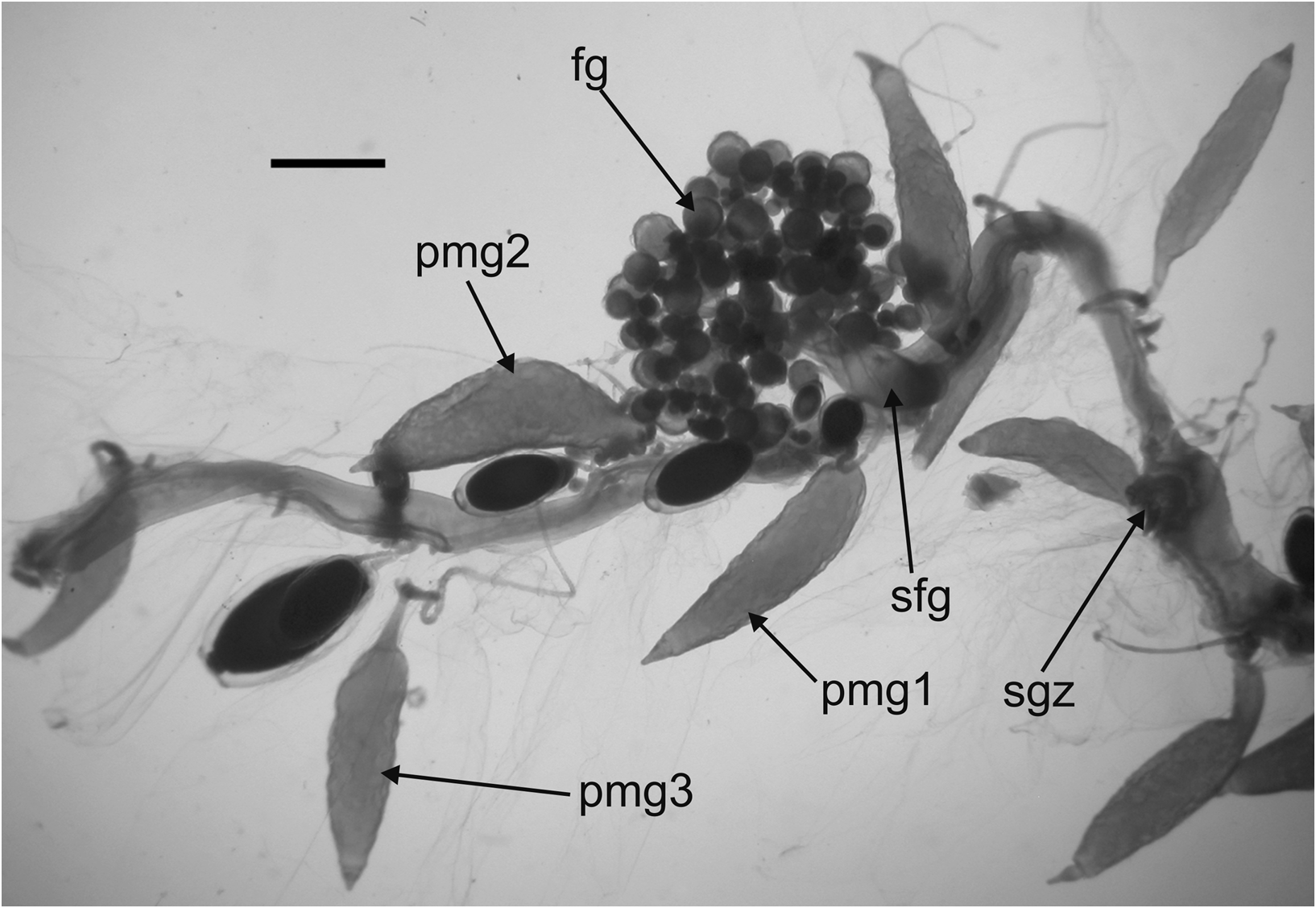

Gonophores: Totton (1965, pp. 56 & 58) gave a detailed description of the arrangement of the male and female gonodendra, noting "On each cormidium there are proximally two or three palpons, probably derived from secondary budding. Distal to them there is a larger palpon with a palpacle that measures 15 mm in length, not fully expanded. From the distal side of its base is budded, in the mid-ventral line, the wide muscular stemmed female gonodendron, with its branches and medusoid gonophores resembling a miniature bunch of grapes. When mature it is about 5 mm in diameter, and capable of a great deal of expansion and contraction. It is situated at about one-third the distance from the last gastrozooid to the next one, and bears a number of reinforcing rings in the stem-wall. Distal to the female gonodendron are three other large palpons with palpacles, occupying the middle region of the cormidium. On the distal side of the base of each and in the mid-ventral line of the stem is a reduced male gonodendron ... It has not been sufficiently described hitherto. It can be seen that each of the male gonophores buds off at an angle of rather more than 120° in the transverse plane from the base of its predecessor to form a lefthanded spiral. When mature the pedicels of the male gonophores grow to the comparatively enormous length of 5 mm. There may be present on each male gonodendron from eight to ten mature male medusoid gonophores, which start to pulsate whilst still attached, but finally detach themselves to swim away and shed their sperms. They are about 6 mm in length and lack tentacles. Each female gonophore ─ up to 0.7 mm in diameter ─ contains a single egg. In the distal region of each cormidium may be found two or three other palpons probably derived from secondary budding. It is not known whether they in turn develop gonodendra".

This basic arrangement can be seen ( Figure 21 View FIGURE 21 ) for one of the JSL specimens. The racemose female gonodendron (fg), with its thickened stalk (sfg), bore no palpons. No mature female gonophores were found with any of the specimens examined. The three male gonodendra present in each cormidium, each associated with a palpon (pmg1-3), included only a few male gonophores, with a maximum length of 2.3 mm, that were obviously still immature ( Figure 22 View FIGURE 22 ). They had a short, broad stalk through which the gastrovascular canal passed, and a widely opened distal mouth.

Nectalia View in CoL -stage: The specimen from JSL II dive 973-DS4 was young ( Figure 23 View FIGURE 23 ) and, although it had clearly developed beyond the Nectalia View in CoL post-larval stage, it still bore the protozooid, with its tentacle bearing larval tentilla. The JSL Dive 1683-D 1 specimen also still possessed six larval bracts, but the protozooid and larval tentilla had been lost. The former specimen included fourteen nectophores, no different from those of the adult specimens, and a couple of nectophoral buds. Only six larval bracts were found, while thirteen Type A bracts were also present. Carré (1971), who studied the larval development of Halistemma rubrum View in CoL , also made brief mention of some young colonies of that species, found in the plankton, but neither referred to them as being at the Nectalia View in CoL -stage nor described them in detail, apart from the larval tentilla. Also, as noted above, the post-larval stage that Vogt (1854) attributed to this species actually is that of an Agalma species.

The larval bracts ( Figure 24 View FIGURE 24 ) measured up to 15 mm in length. They were thickest at their proximal ends, thinning distally, with the upper surface convex and the lower one concave. The distal end was roundly pointed, and slightly proximal to it there were two rounded, lateral teeth. On the upper surface of the bract there were two pairs of patches of ectodermal cells, usually slightly asymmetrically placed and varying in size. Often these patches had been rubbed off but, usually, their outlines could be seen. The cells within these patches possessed densely staining nuclei, and were presumed to be sites of bioluminescence.

The bracteal canal followed the contours of the lower, median wall of the bract from close to its proximal end to almost its distal end. The canal was thickened in the proximal region, where the attachment lamella was present, but distally it was distinctly thinner. It continued along the median wall, but shortly before the distal end of the bract it penetrated into the mesogloea and continued, as a thin canal, to end below a cup shaped indentation filled with nematocysts. These nematocysts were identified by Carré (1971) as microbasic euryteles, but we were not able to confirm this.

The protozooid ( Figure 25 View FIGURE 25 ) showed no great differences from the adult gastrozooids, with all three main regions, proximal basigaster, stomach and distal proboscis, being of approximately the same length and diameter.

The larval tentilla, which were first described and illustrated by Keferstein & Ehlers (1861, Plate II, figs. 12–15, 17), were distinctly different from the adult forms. They consisted of a long, highly contractile proximal pedicel, and a long sac-like structure capped, distally, by a hemispherical dome from the centre of which projected a short terminal filament. There were no signs of any nematocysts on either the majority of the dome or the terminal filament. Two main structures were present in the sac. The double elastic band ran the entire length of the sac, and was particularly noticeable in its proximal region, where the coiling of the two bands around each other was obvious. The other structure was the cnidoband, the proximal end of which lay distally in the sac at the base of the domed terminal process. It extended to approximately half the length of the sac. Stenoteles and anisorhizas, as identified by Carré (1971), were present in the cnidoband, but whereas the latter occurred throughout, the former were restricted to each side of the distal three-quarters of its pendulous section. There were about 80 stenoteles present, measuring c. 70 x 23 µm, which was slightly larger than those on the adult tentilla. However, the anisorhizas were slightly smaller, measuring c. 40 x 9 µm. The number of stenoteles present was considerably higher than the dozen that Carré (1971) found on each side of the cnidoband of her specimens. Whether this difference can be accounted for by the differences in age of the specimens cannot be determined at present.

Remarks: The nectophores of Halistemma rubrum are easily distinguished from those of all other Halistemma species by the incompleteness of the basic ridge system. The absence of a mouth plate is also a useful diagnostic character, although it is not unique to this species. In addition, the almost vestigial involucrum at the base of the cnidoband of the tentillum, and the presence of a tightly coiled tapering process at the end of the terminal filament, rather than a cupulate process, help to distinguish H. rubrum from other Halistemma species.

Distribution: There have been numerous records for Halistemma rubrum since Vogt (1852a) first described it; the most reliable of which come from the Mediterranean Sea as, to date, it is the only Halistemma species that has been found there. Most records are from the western basin (e.g. Carré, 1971, Bouillon et al., 2004) but there are a few from the eastern basin, including the Adriatic Sea (e.g. Gamulin & Kršinić, 2000) and off Lebanon (e.g. Lakkis & Zeidane 1997).

Since the nectophores of Halistemma cupulifera have not until now been described, and together with the discovery recently of two new species, H. transliratum Pugh & Youngbluth, 1988 and H. maculatum sp. nov., all records from other regions need to be treated with some caution. For instance, as we will show, the type "e" and "f" nectophores that Totton (1954) ascribed to H. rubrum actually belong to other Halistemma species , namely H. cupulifera and H. maculatum sp. nov., respectively.

The present records for the North Atlantic Ocean came from the Gulf of Maine and the Bahamas. There are several other unverified records for the western North Atlantic, and Leloup (1936), for one, also cites its presence at various positions in the eastern North Atlantic. These records, if true, indicate that Halistemma rubrum appears to have a widespread distribution in that region, including the Gulf of Mexico ( Pugh & Gasca, 2009) and Caribbean ( Stepanjants, 1975).

In the South Atlantic Ocean Halistemma rubrum has been reported from off South Africa and Namibia (e.g. Pagès & Gili, 1992) and off Brazil ( Nogueira & Oliveira 1991). Margulis (1969) found it to be the second commonest physonect in samples collected throughout the Atlantic Ocean, and found that its most northerly occurrence was at 50°22’N, 21°13’W, the most southerly at 42°04’S, 38°58.9’W, being present at all depths between the surface and 1700 m.

Halistemma rubrum View in CoL has also been recorded on a number of occasions throughout the Indian Ocean but, as noted above, some of Totton's (1954) records belong to different species. Daniel (1985) gives the most comprehensive data for that region, with further data from the eastern Indian Ocean being given by Musayeva (1976).

Although Stepanjants (1967, 1977a, b) states that H. rubrum View in CoL has a fairly widespread distribution in the warmer waters of the Pacific Ocean, most other records are concentrated in three areas; in the Humboldt Current, off Chile ( Pagès et al., 2001); in western waters from the Moluccas ( Bedot, 1896), Vietnam ( Leloup, 1956), Taiwan ( Yu, 2006), and Chinese waters (e.g. Zhang, 2005); and finally off southern California and Baja California ( Alvariño, 1967, 1991). However, some of these identifications must be doubtful. For instance Zhang, whose fig 2D of H. rubrum View in CoL , shows a nectophore with a large mouth plate, which is not a character for this species. Nonetheless, three of the specimens examined in this study came from the southern end of the Gulf of California. Four other specimens of Halistemma sp. collected during the same cruise probably belonged to H. rubrum View in CoL , but they were not examined,. Two of these also came from DR0335, at 284 and 198 m depth; one was collected during DR0340 (23°41.6'N, 106°05'W) at 201 m; and another during DR0341 (24°18.9'N, 109°11.9'W) at 217 m.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Halistemma rubrum (Vogt, 1852)

| Pugh, P. R. & Baxter, E. J. 2014 |

Halistemma rubra

| Carre, D. 1974: 211 |

| Tregouboff, G. & Rose, M. 1957: 351 |

| Totton, A. K. & Fraser, J. H. 1955: 3 |

Stephanomia rubra

| Alvarino, A. 1981: 394 |

| Daniel, R. & Daniel, A. 1963: 194 |

| Leloup, E. 1935: 3 |

| Bigelow, H. B. 1911: 284 |

Agalma minimum

| Haeckel, E. 1869: 46 |

Halistemma punctatum L. Agassiz, 1862 , p. 369

| Haeckel, E. 1888: 367 |

| Agassiz, L. 1862: 369 |

Agalma rubra

| Vogt, C. 1852: 522 |