Amalosia, Wells & Wellington, 1984

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.5343.4.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:358CE9AF-F36D-4EEA-89E6-8B64FEFE0772 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8336221 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03FC6E41-F469-885F-FF28-F1FB453FDCEB |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Amalosia |

| status |

|

Recognised Amalosia View in CoL View at ENA species,

including transfer of Nebulifera robusta to Amalosia

Amalosia rhombifer ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 ). The type locality for A. rhombifer was originally described as ‘W Australia’ (i.e., West or Western Australia) ( Gray 1845) but the lectotype (BMNH xxii.3a; Fig. 6A View FIGURE 6 ) is stated to be from ‘N Australia’ (North or Northern Australia) by Cogger et al. (1983). These collection localities are taken to be outside of Queensland. The lectotype and the morphologically consistent looking specimen in the same jar (BMNH xxii.3b; Fig. 6B View FIGURE 6 ) both have two enlarged postcloacal spurs on each side, a character state that is only standardly seen in Queensland in populations in north-western Queensland (i.e., Mt Isa, Cloncurry, Boulia, Doomadgee region). This is a rare condition in all other Queensland Amalosia , which almost always have three or more spurs on each side ( Tables 1 View TABLE 1 and 2). The far north-west Queensland populations fall in a lineage among Northern Territory and Western Australian clades ( Figs. 2 View FIGURE 2 , 3 View FIGURE 3 ). Although this population cannot be assigned to A. rhombifer until a full assessment of the ‘ A. rhombifer ’ populations across northern Australia is complete, the north-west Queensland population serves as a useful surrogate for A. rhombifer sensu stricto and provides a means of diagnosing this taxon from all other members of the A. rhombifer group occurring in Queensland. It is herein referred to as A. cf. rhombifer , including in the Comparison section of each species description and in its own ‘species account’ following these.

Amalosia lesueurii ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ). As currently recognised. Assessment of A. lesueurii herein focussed on northern populations, to compare with congeners in northern New South Wales and Queensland. These comparisons are presented in the species accounts below. Material examined is listed in the Appendix.

Distributed from the Stanthorpe region in south-east Queensland ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 ), south through the New England Tableland, then with a break to populations in central-eastern New South Wales, which extend coastally from Newcastle, through the Sydney region and south of Wollongong. Rock-associated, in dry forests and heathlands. In northern New South Wales and south-east Queensland, A. lesueurii is restricted to elevated (primarily granite) areas associated with the New England Tableland and the Granite Belt ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ). All purported records from the adjacent coastal lowlands (e.g., on Atlas of Living Australia) are likely to be misidentified A. jacovae ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ), which was relatively recently discovered in coastal northern New South Wales ( Greenlees & Bezzina 2014). Known to occur in very close proximity to A. hinesi sp. nov. west of Stanthorpe, but ecologically separated in being saxicoline (vs A. hinesi sp. nov. on trees and fallen debris).

Amalosia jacovae ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 ). As recognised by Couper et al. (2007), with the exception that the unresolved ‘additional material’ they identified in the Leslie Dam/Warwick, Inglewood and Texas Caves areas, is assigned to A. hinesi sp. nov. herein. The unresolved ‘additional material’ they included from Blackdown Tableland is indeed A. jacovae . Identification of A. jacovae from congeners is covered in the Comparison sections of the species descriptions below. Material examined is listed in the Appendix.

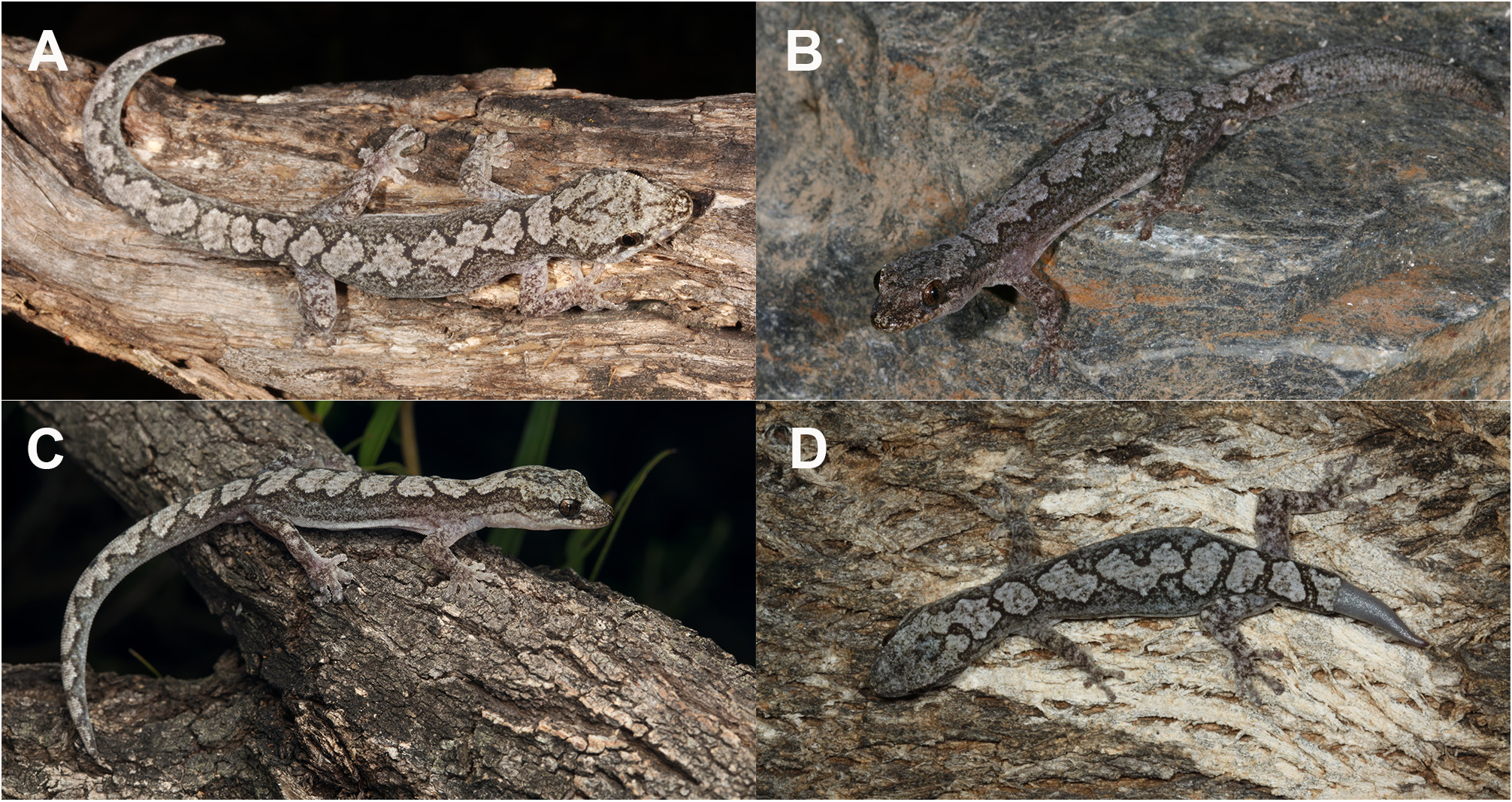

Amalosia jacovae is distributed from Grafton in New South Wales ( Greenlees & Bezzina 2014), coastally north through south-east Queensland to about Gympie (including offshore islands of North Stradbroke, Moreton, and Fraser Islands ), and inland to apparently isolated populations at Kroombit Tops, Blackdown Tableland and Expedition Range ( Fig.4 View FIGURE 4 ).Itisgenerallyfoundinwoodlandsonlowfertilitysoils,particularlythosedominatedby‘spottedgums’( Corymbia spp. ),and in mixed coastal woodlands (e.g., on the offshore islands in south-east Queensland).The isolated populations in the north-west of the range are in elevated woodlands. Arboreal; typically found foraging on tree trunks at night, particularly around small flaking pieces of bark on the bottom few meters of the trunks of spotted gum trees ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 ).

Known to co-occur with A. queenslandia sp. nov. in micro-sympatry (i.e., on adjacent trees) at Kroombit Tops (H. Hines, collections). Not known to co-occur with A. hinesi sp. nov. but their distributions may come close in the Toowoomba region; for example, an individual photographed at Southbrook (west of Toowoomba) has the characteristics of A. jacovae ( Fig. 8D View FIGURE 8 ). Not known to co-occur with A. lesueurii ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ). Records of A. lesueurii in the coastal lowlands of north-east New South Wales (e.g., on the Atlas of Living Australia) are all likely A. jacovae (e.g., Greenlees & Bezzina 2014; Swan et al. 2022), with all verified records of A. lesueurii in northern New South Wales coming from elevated areas of the New England Tableland ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ).

Amalosia obscura . As currently recognised, and not dealt with in this revision because it is restricted to northern Western Australia and is readily diagnosed from Amalosia in eastern Australia by having a more banded or mottled dorsal pattern rather than a pale zigzag or blotched vertebral markings ( Cogger 2014; Wilson & Swan 2021).

Amalosia robusta ( Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 ). This species was originally described as Oedura robusta Boulenger, 1885 . It was included in Amalosia by Wells & Wellington (1984) when the genus was erected but that combination was not used due to a lack of justification for recognising Amalosia at that time. It was subsequently placed in a monotypic genus, Nebulifera , by Oliver et al. (2012), based primarily on genetic data and the following character states: dorsal scales minute, smaller than ventrals; cloacal spurs two to five; dorsal pattern consisting of white blotches on a dark background (and not as a vertebral ‘stripe’), moderately large size (SVL up to 80 mm); a strongly depressed and widened tail ( Oliver et al. 2012). Subsequent work by Skipwith et al. (2019), based on phylogenomic analyses of thousands of ultraconserved genetic elements, questioned the validity of Nebulifera . Amalosia jacovae [a species not included in the genetic study by Oliver et al. (2012)] was shown to be a deeply divergent lineage basal to the Amalosia clade, followed by ‘ N. robusta ’, and then A. lesueurii , A. rhombifer and A. obscura ; a result not supporting the placement of ‘ N. robusta ’ in its own genus. The phylogeny herein ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 ), based only on a single mtDNA gene, shows the same general topology. Skipwith et al. (2019) stated “Our finding that Amalosia is paraphyletic relative to Nebulifera suggests that the latter genus may need to be synonymized.” However, no taxonomic changes were made.

The species described herein also make the morphological traits proposed by Oliver et al. (2012) to define Nebulifera less diagnostic. Amalosia also have minute dorsal scales smaller than the ventrals, and essentially the same range in cloacal spur number (2–6, Tables 1 View TABLE 1 , 2). Additionally, Amalosia do not always have a pale dorsal pattern as a vertebral ‘stripe’, with variation in some species including pale blotches on a dark background (e.g., A. hinesi sp. nov., Fig. 11C, D View FIGURE 11 ); broadly similar to the ‘ N. robusta ’ pattern. Another trait defining Nebulifera was the substantially larger size of this species (SVL average 70 mm; max. SVL 80 mm) compared to Amalosia described at that time (although A. lesueurii had been recorded up to 67 mm; Cogger 1957; Swan et al. 2022). The descriptions herein reduce this difference and show more of a continuum in body size, with A. saxicola sp. nov. growing to at least 65 mm SVL and considerably larger than A. capensis sp. nov. and A. queenslandia sp. nov. (both max. SVL about 50 mm). The most distinctive trait for ‘ N. robusta ’ compared to Amalosia is the strongly depressed and widened tail. However, tail shape can be highly variable within well-supported gecko genera; for example, Phyllurus species range from flared, flattened tails (e.g., P. platurus ) to cylindrical tails (e.g., P. caudiannulatus ), and the Diplodactylus conspiculatus group have short, flattened tails compared to the more elongate tails of other Diplodactylus species.

Herein, we formally synonymise Nebulifera Oliver et al. 2012 with Amalosia Wells & Wellington 1984 , reestablishing the binomial combination Amalosia robusta ( Boulenger 1885) as cited by Wells & Wellington (1985).

TABLE 1. (Continued)

TABLE 2. (Continued)

Amalosia robusta is readily distinguished from other Amalosia species by its large size, flattened tail (particularly for regenerated tails, e.g., Fig. 9B View FIGURE 9 ), dorsal pattern of obvious pale blotches on a dark background, and nape blotch separated, or nearly so, from the pale ‘blotch’ that covers the top of the head (e.g., Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 ). It is therefore not included in the Comparison sections below. It is a large arboreal gecko found through woodlands and rocky areas over a broad distribution, from coastal areas around Newcastle and inland areas from south of Dubbo in New South Wales, north to coastal areas around Rockhampton and inland areas to around Emerald in Queensland. It co-occurs with other Amalosia species across this range ( A. lesueurii , A. hinesi sp. nov., A. jacovae , A. queenslandia sp. nov.).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.