Pan paniscus, Schwarz, 1929

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6700973 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6700593 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03FA8785-4003-9F62-FA8E-F938F9B8B8C1 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Pan paniscus |

| status |

|

Bonobo

French: Bonobo / German: Bonobo / Spanish: Bonobo

Other common names: Dwarf Chimpanzee, Gracile Chimpanzee, Pygmy Chimpanzee

Taxonomy. Pan satyrus paniscus Schwarz, 1929 View in CoL ,

DR Congo, 30 km south of Befale, south of upper Maringa River .

This species is monotypic.

Distribution. C DR Congo in the basin formed by the Congo River to the N and W, bounded by the Lualaba River in the E, and the Kasai/Sankuru rivers in the S; the Congo River forms a biogeographical barrier separating Bonobos from gorillas and Chimpanzees. View Figure

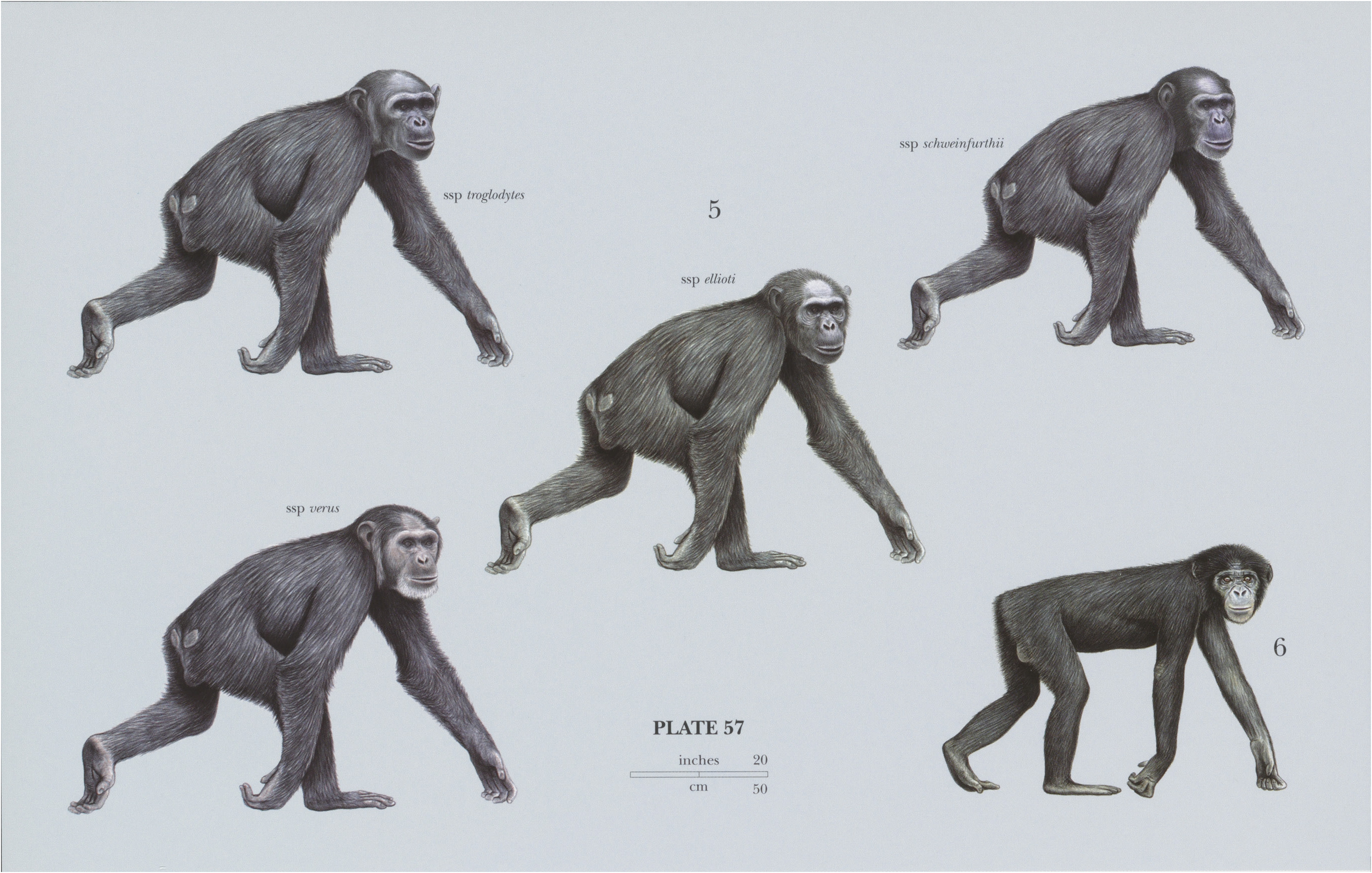

Descriptive notes. Head-body 73-83 cm (males) and 70-76 cm (females); weight 36— 43 kg (males) and 26-36 kg (females). The Bonobo is moderately sexually dimorphic. It is similar in size and appearance to Chimpanzees (PF. troglodytes ) but limbs are more gracile and their appearance is more agile. Bonobos have a smaller head than Chimpanzees and shorter and very rounded skulls usually covered by long hair on the sides of the head. Face is black, lips are pink, and there are long whiskers on the cheeks. Adult Bonobos may retain a white pygal tail tuft (this is not visible beyond infancy in other African great apes).

Habitat. Closed, moist, mixed, mature, secondary, seasonally inundated, and swamp forest. Populations of Bonobos in the western and southern parts of their range inhabit mosaics of swamp forest, dry forest, marshy grassland, and savanna woodland. The undulating terrain is mostly under 500 m elevation.

Food and Feeding. More than 50% of the diet of the Bonobois fruit, supplemented with leaves, stems, shoots,pith, seeds, bark, flowers, truffles, fungus, and honey. At one site, 142 species are eaten. Measured in feeding time, the diet is 68% fruit; 29% leaves, pith and flowers; and 3% animal matter. Bonobos appear to depend more on terrestrial herbaceous vegetation, including aquatic plants, than do Chimpanzees. They forage in streams and marshy grasslands, and they wade waist-deep in water to gather stems and roots of aquatic vascular plants and algae. Animal prey include insect larvae, ants, termites, earthworms, small reptiles, birds, and medium-sized mammals such as duikers, dwarf galagos, and monkeys. They do not hunt frequently, and patterns of hunting vary among populations of Bonobos, from a single individual stalking on the ground to arboreal hunting by several group members. Both male and female Bonobos hunt and adult female Bonobos usually control meat-sharing. Recently, cannibalism has been observed. Sharing of both plant and animal food items among unrelated individuals is known. Unlike Chimpanzees, Bonobos rarely use tools in the acquisition of food.

Breeding. Sexual behavior is an everyday event and sexual interactions occur between all age and sex classes. Testes and body size of male Bonobos increase at 8-9 years old, and it is thought that males reach sexual maturity by age ten. Female Bonobos start cycling at 9-12 years, followed by a period of adolescent infertility. They exhibit a striking pink genital swelling that is maximally tumescent around the time of ovulation. There is a high degree of variability in duration of swellings, offering options of concealment. Mating among community members appears to be promiscuous and opportunistic. Competition among male Bonobos for access to females does not usually take the form of overt aggression, nevertheless males exhibit a linear hierarchy that influences both mating and reproductive success with dominant males siring more offspring. Bonobos do not form consortships, instead dominant males establish amicable relationships with their mates. Females mate with many males. Females produce theirfirst offspring at 13-14 years of age, following a pregnancy of about eight months. In captivity, gestation averages 224-239 days. There is no birth season. Infants have a white pygaltail tuft and a black face from birth. Suckling and maternal care are maintained until the nextsibling is born. Interbirth intervals average 4-8 years at onesite, and eight years at another. Offspring share their mothers’ night nests until they are weaned. Infanticide by male Bonobos has not yet been observed; however, there are records of the kidnapping of infants by females with the subsequent death of the infant.

Activity patterns. The Bonobo is diurnal and semi-terrestrial. They spend 35-61% of their day foraging, 13-37% resting, and 15-25% travelling; 44% of their days are spent in trees and 56% on the ground. About 18% of foraging was in swamps or on the ground, searching for pith or leaves and sitting down to process a stem or shoot on average every 10 m. They travel rapidly when covering large distances between two food sources. Bonobos build new nests every night to sleep in, usually 15-30 m above the ground. Although construction of most nests takes only about four minutes, these night nests are often elaborate—a single nest may incorporate branches and foliage from several trees. Bonobos sometimes place loose leafy twigs on top of their bodies while lying in their nests, and sometimes they drape vegetation over their heads and shoulders as hats and umbrellas to provide protection against heavy rain. Bonobos also regularly construct less elaborate arboreal nests for resting during the day. They are highly selective in their choice of nesting tree species and nest sites and regularly reuse specific sites and locations.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Bonobos live in multimale-multifemale, fission-fusion communities of 10-120 members. They vary group size when foraging by splitting into smaller mixed-sex parties averaging 4-8-22-7 individuals. They travel 2-3 km/day, on average, occasionally 5-8 km/day. The annual home range of a community is 22-58 km?, and overlap between community ranges is 40-66%. Bonobos of both sexes occasionally make use of a ritual called “branch dragging” whereby they drag saplings noisily to initiate and coordinate group travel. Males and females roam together all year round. Females emigrate upon reaching sexual maturity, but males are generally philopatric, remaining in their natal group. Male Bonobos are tolerant and cooperative; aggressive behavior plays a minor role not only between sexes independent of reproductive status, but also between males in the acquisition of social status and thus determination of rank, as well as in intercommunity encounters. Independent of relatedness, strong and lasting bonds between adult male Bonobos are rare, while alliances among female Bonobos are common, strong and may last several years. Females form coalitions and support each other against males, with the result that females are considered co-dominant with males. Adult male Bonobos form friendly pair-relationships with unrelated adult females, and high-ranking males invest more in these relationships than do lower ranking individuals. Mother-son bonds are strongest, highly important for the social status of the son, and last far into adulthood. Grooming between Bonobos of the opposite sex is more frequent and prolonged than grooming between same-sex pairs. Individuals of all ages and both genders engage in sexual activity. Non-conceptive sex among Bonobos is thought to contribute to tension regulation and reconciliation and reflects acknowledgement ofstatus.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Listed under Class A in the African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Killing or capture of Bonobos for any purpose is against national and international laws, but law enforcement is generally weak. The total population size of the Bonobo is uncertain because only 30% ofits historic range has been surveyed. Estimates from the four known Bonobo strongholds, based around protected areas, suggest a minimum population of 15,000-20,000 individuals. Numbers are still dropping—one-third of the population at one site was lost between 2006 and 2010. Most habitat destruction is by slash-and-burn subsistence agriculture, which is most intense where human densities are high or growing. Industrial logging, mining, and agriculture do not yet occur on a large scale in the Bonobo’s habitat, but they are serious future threats. An underlying threat to Bonobois the volatile political situation in DR Congo, together with institutional, social, and economic decline in recent decades—all exacerbate the unsustainable exploitation of natural resources and result in the elimination of wildlife. By far the greatest threat to Bonobos is poaching for the commercial bushmeat trade. Bushmeat was consumed in 28% of households surveyed in 2008 in DR Congo's capital city, Kinshasa, which has a population of nine million people. It has been estimated that nine tons of bushmeat are extracted daily from a 50,000km* conservation landscape within the Bonobo’s habitat. In one region, a “closed season”is being imposed,as part of the effort to combat hunting of Bonobos. In some areas, local taboos against eating Bonobo meatstill exist, while in others, these traditions are disintegrating due to changing cultural values and population movements caused by civil unrest. There is not only a massive demand for bushmeat in the cities, but also armed forces, both rebel factions and poorly paid government soldiers, add to that demand besides facilitating the flow of guns and ammunition. There are strong cultural attachments to bushmeat in DR Congo. A recent conservation prioritization process recognized that reducing Bonobo mortality caused by poaching must be the highest priority for conservation action. Habitat loss through deforestation and fragmentation ranked second, although it was acknowledged that forests are often severely depleted of their wildlife before habitat destruction begins. Disease was also considered a potential future threat. Indirect threats to Bonobo survival include weak law enforcement, commercial bushmeat trade, uncontrolled proliferation of weapons and ammunition, human population growth, expansion of slash-and-burn agriculture, insufficient subsistence alternatives, and large-scale commercial activities (industrial agriculture, logging, mining, petroleum drilling and exploration, and associated development of infrastructure). Many international and local conservation organizations are working with the government of DR Congo toward protection and long-term survival of Bonobos and to support the national park authority with its mission. New protected areas are planned and have been created primarily to safeguard this species, which is endemic to DR Congo.

Bibliography. Coolidge & Shea (1982), Drews et al. (2011), Fowler & Hohmann (2010), Fruth (1995), Fruth et al. (1999), Gerloff et al. (1999), Groves (2001), Heistermann et al. (1996), Hohmann (2001), Hohmann & Fruth (2008, 2011), Idani et al. (1994), IUCN & ICCN (2012), Jungers & Susman (1984), Morbeck & Zihlman (1989), Reinartz et al. (2013), Surbeck, Deschner et al. (2012), Surbeck, Fowler et al. (2009), Surbeck, Mundry & Hohmann (2010).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.