Pseudonannolene Silvestri, 1895

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2023.867.2109 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:8DEF295C-A8B1-4A6B-B873-B30949F64E07 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7907833 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F887BA-133C-B170-4D7D-FDE7FADC52DB |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Pseudonannolene Silvestri, 1895 |

| status |

|

Genus Pseudonannolene Silvestri, 1895 View in CoL

Pseudonannolene Silvestri, 1895a View in CoL 34: 775.

Pseudonannolene View in CoL – Silvestri 1895b: 7; 1896: 170; 1897a: 651. — Cook 1895: 6. — Brölemann 1902a: 120; 1929: 7. — Carl 1913a: 174; 1914: 855. — Attems 1926: 206. — Verhoeff 1943: 269. — Jeekel 1971: 113. — Mauriès 1977: 248; 1983: 250; 1987: 170. — Hoffman 1980: 91. — Hoffman & Florez 1995: 116. — Hoffman et al. 1996: 14. — Golovatch et al. 2005: 279. — Iniesta & Ferreira 2013a: 92 View Cited Treatment . — Shelley & Golovatch 2015: 7. — Hollier et al. 2017: 218. — Iniesta et al. 2020: 5.

Type species

Pseudonannolene typica Silvestri, 1895 View in CoL , by subsequent designation ( Silvestri 1896: 170).

Etymology

From the Greek prefix ‘pseudo’ = ‘false, not genuine’, + ‘ nannolene ’, in reference to the apparent similarity with the cambalidean genus Nannolene Bollman, 1887 . The name is regarded as a feminine noun.

Diagnosis

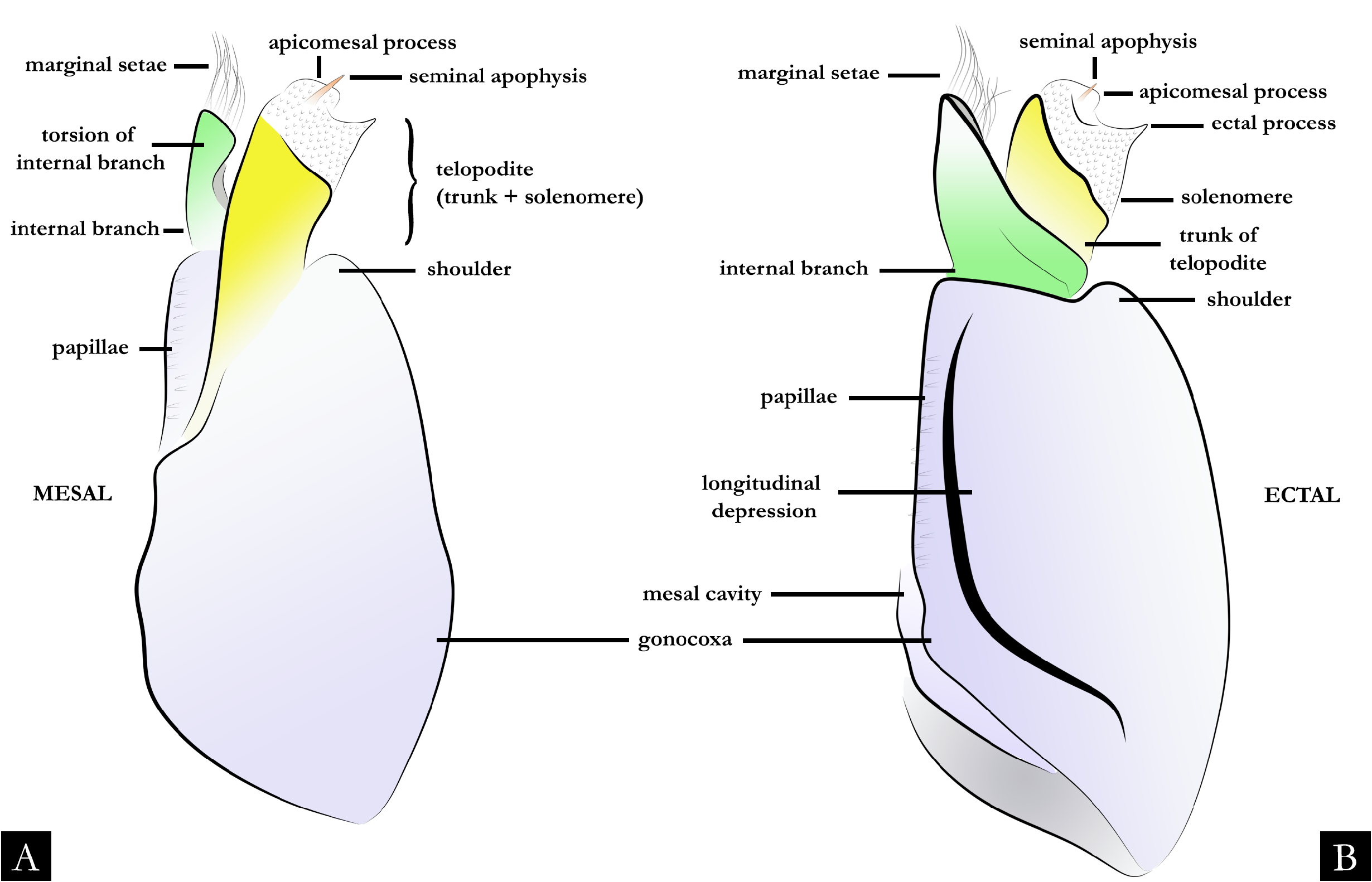

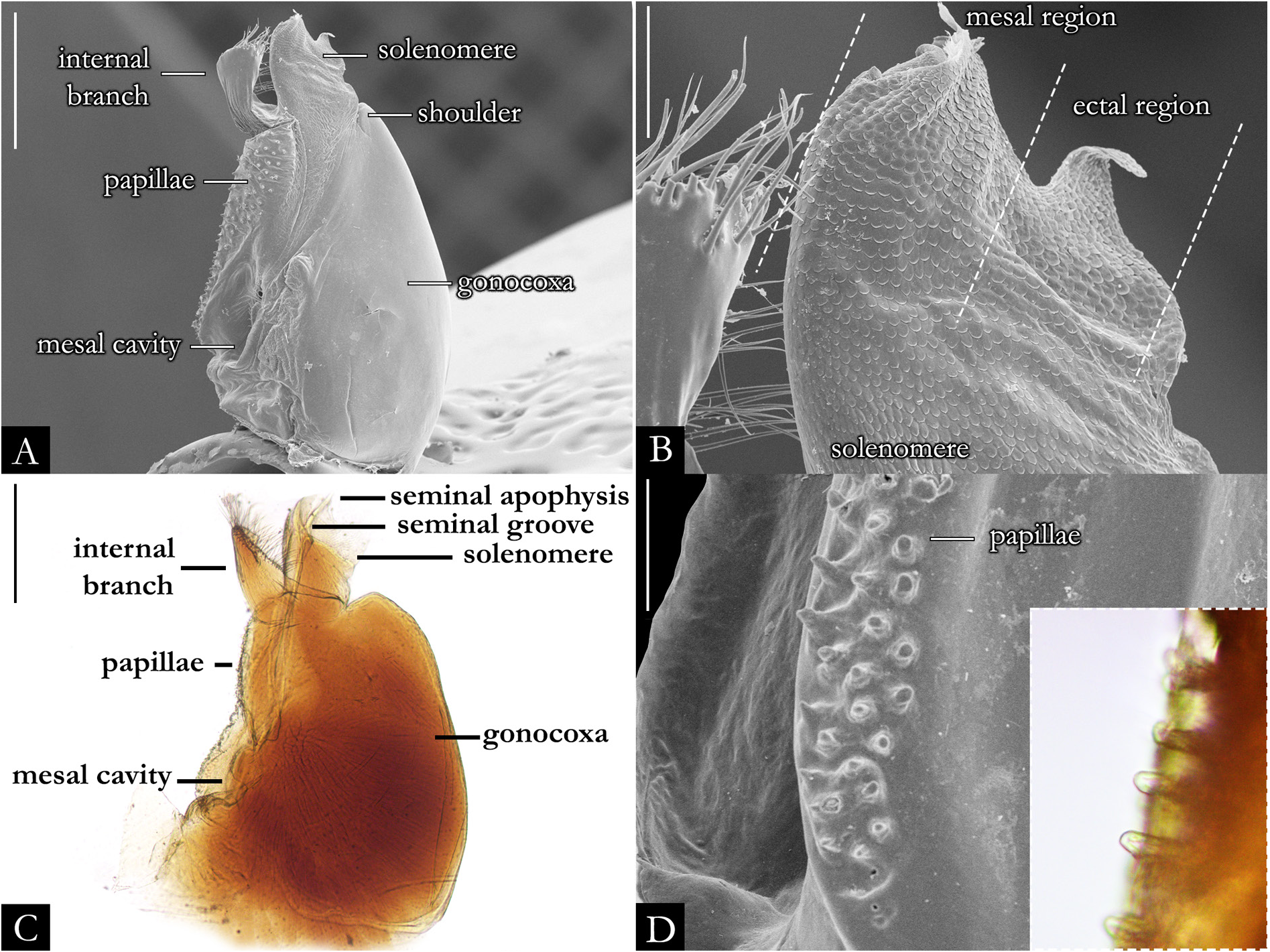

A genus of Pseudonannolenidae easily diagnosed by the presence of a longitudinal suture on the promentum ( Fig. 19E–F View Fig ). Gonopods of Pseudonannolene resemble those of Epinannolene (Pseudonannoleninae) by the presence of rows of papillae on the mesal region of the gonocoxae and by two well-developed distal branches, but differ by the presence of a narrow internal branch enfolding the telopodite basally ( Fig. 35A, C, E View Fig ), vs internal branch parallel to the telopodite in Epinannolene . Females of Pseudonannolene are recognized by the vulvae connecting only distally ( Fig. 39A View Fig ), vs vulvae connected along their entire mesal portion in Epinannolene .

Redescription

MEASUREMENTS. Euanamorphic species, body in adults with 50–81 body rings (1–3 apodous + telson); length 20–137.5 mm; maximum midbody diameter 1.2–6.8 mm.

COLOR. Variable, from depigmented (troglomorphic species) ( Fig. 18B, E View Fig ) to darker brown or blackish ( Figs 17 View Fig , 18A–D, F View Fig ); most species with brownish body and metazonites with a reddish posterior band.

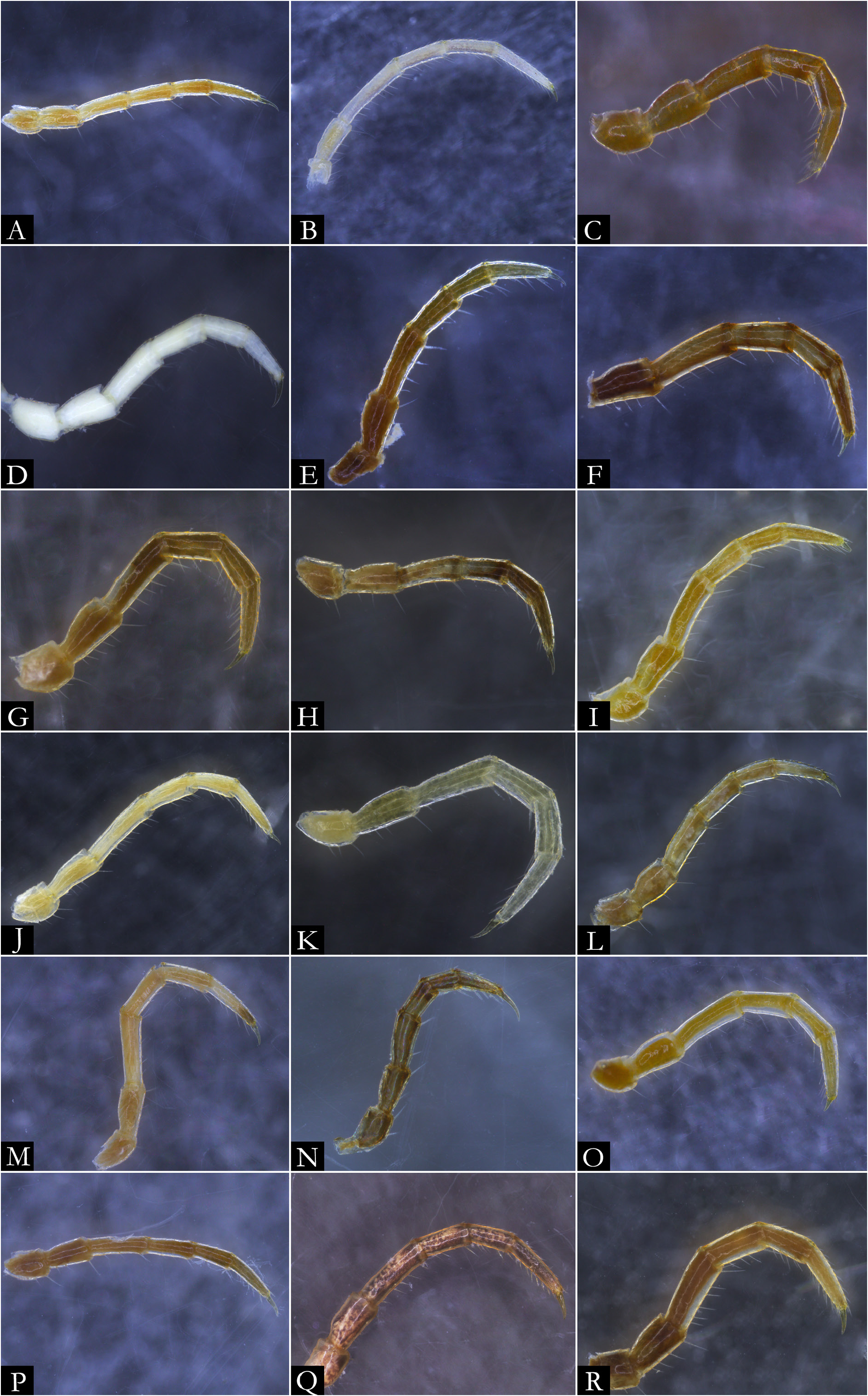

HEAD. Slightly convex, with a row of labral setae and 3+3 supralabral setae ( Fig. 19A–B View Fig ); scattered setae on frontal region in P. centralis and P. occidentalis ( Fig. 19B View Fig ). Labrum with three medial teeth ( Figs 19A–B View Fig , 23A View Fig ). Antennae usually elongated, slender ( Figs 21–22 View Fig View Fig , 163–164 View Fig View Fig ); bacilliform setae on antennomere V and VI ( Figs 21B–E View Fig , 22B–D View Fig ), and four large apical cones ( Figs 21B, D View Fig , 22B, E View Fig ). Ommatidial cluster well-developed; ommatidia depigmented to brownish, elliptical, arranged horizontally in 4–6 rows ( Fig. 19D View Fig ). Mandibular stipes usually with margin narrow; external tooth long, with 2–3 lobes; internal tooth with 4–5 lobes decreasing in size from posterior to anterior ( Fig 20C–E View Fig ); number of pectinate lamellae variable ( Fig. 20D–E View Fig ), fringes positioned basally ( Fig. 20E–F View Fig ). Molar plate with distal transverse groove ( Fig. 20A–B, D View Fig ). Epipharynx with 1+1 lateral keel and one medial keel, long fringes positioned distally; outer and inner subcylindrical palps ( Fig. 24 View Fig ).

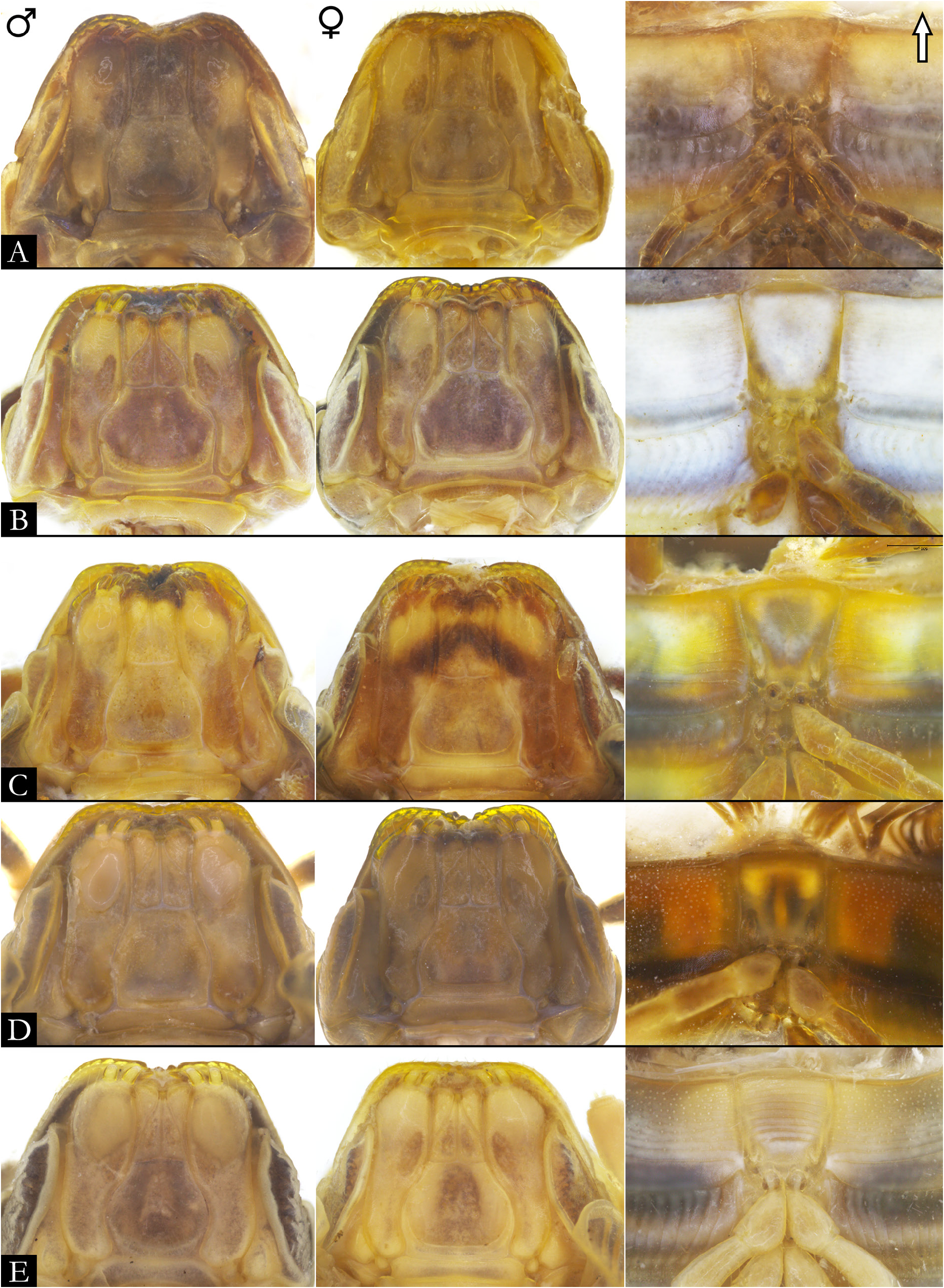

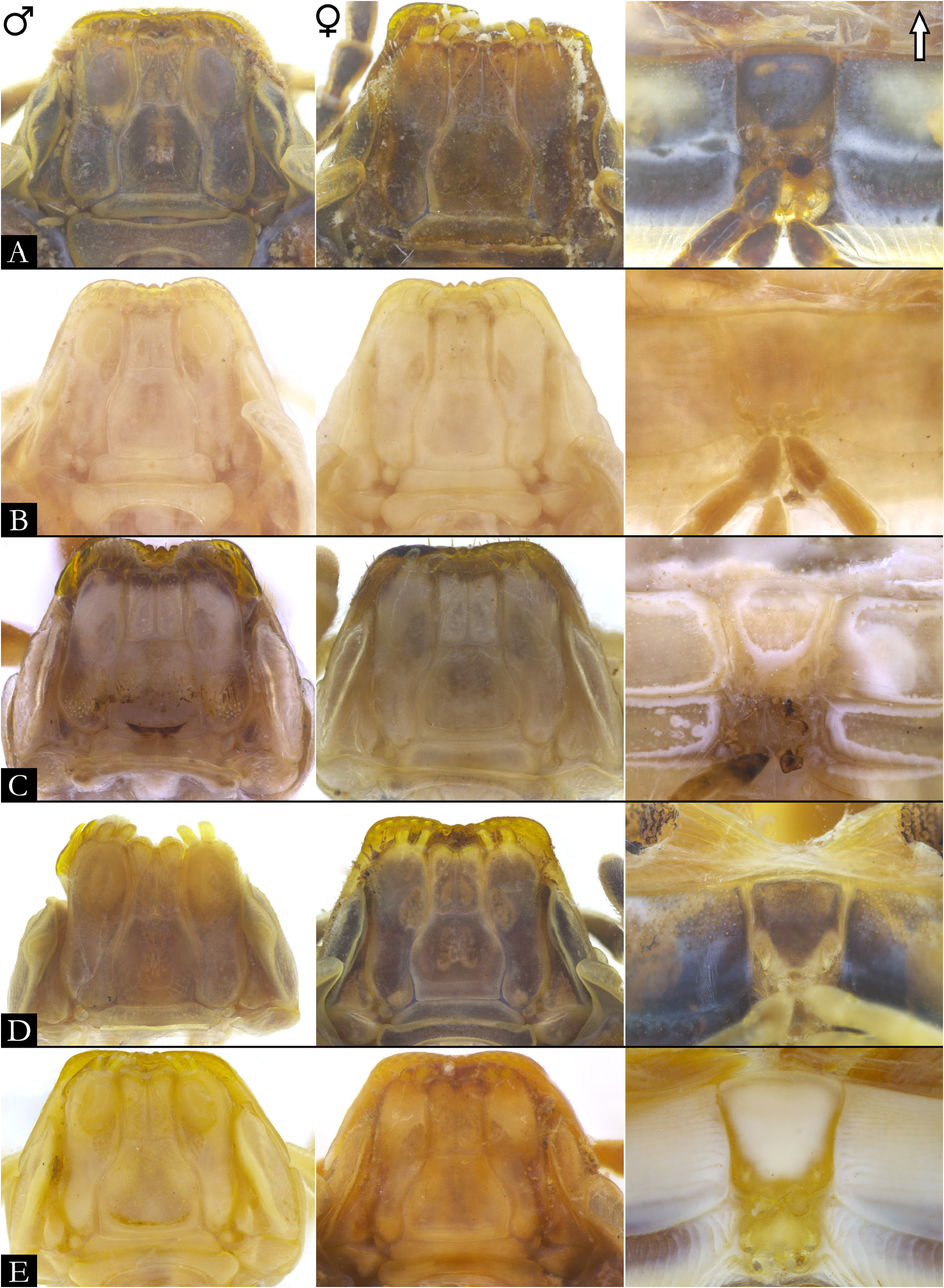

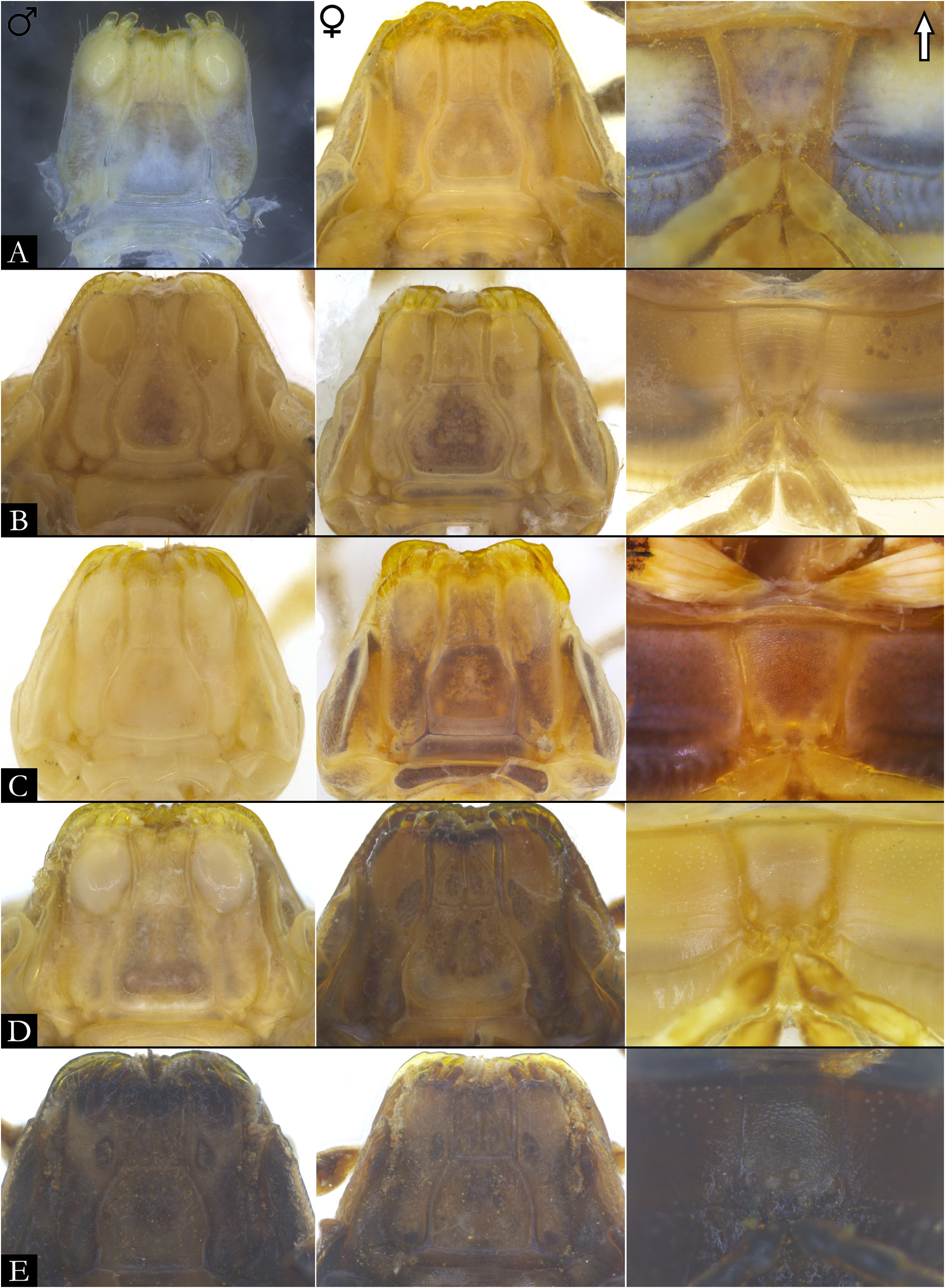

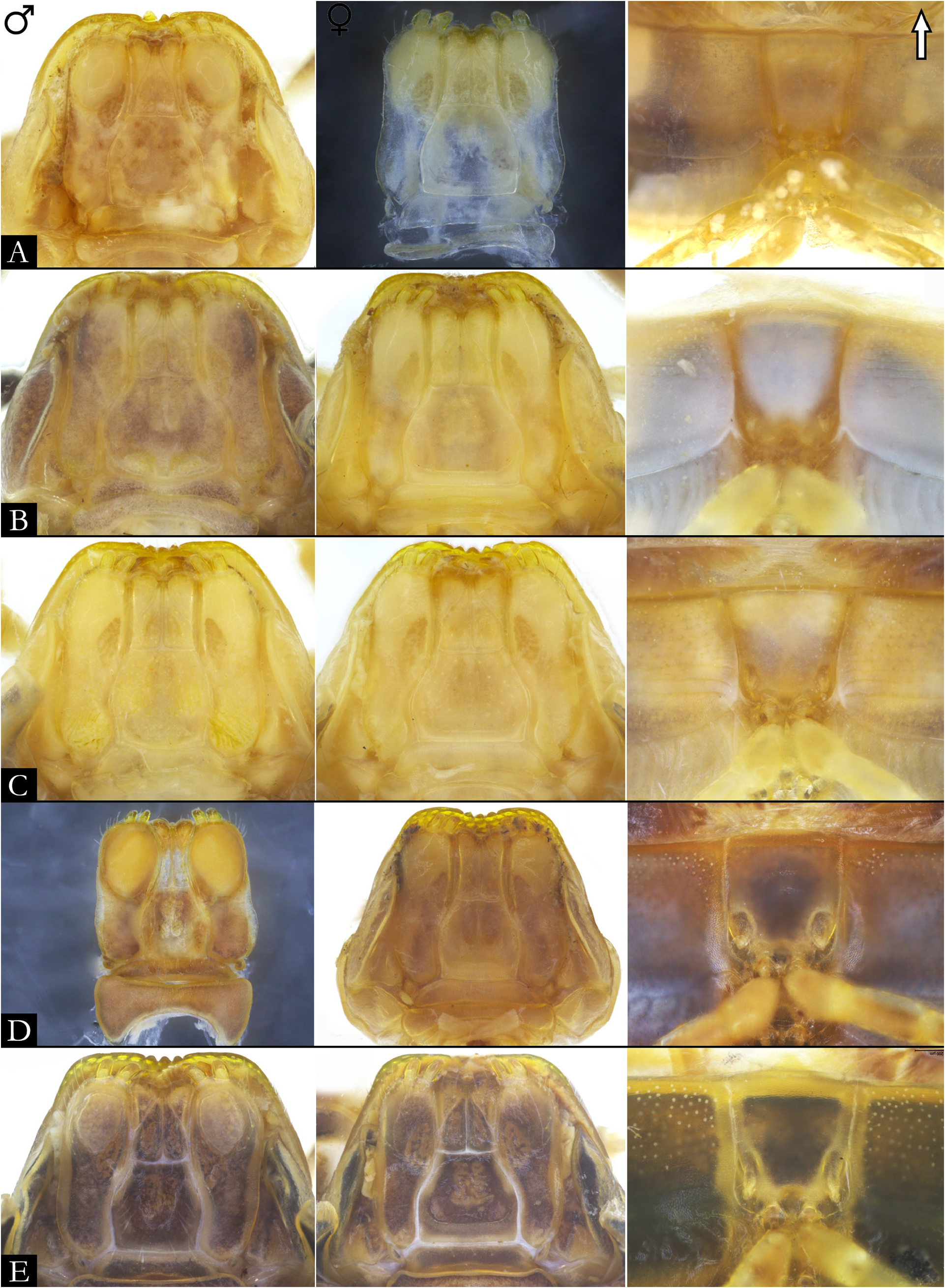

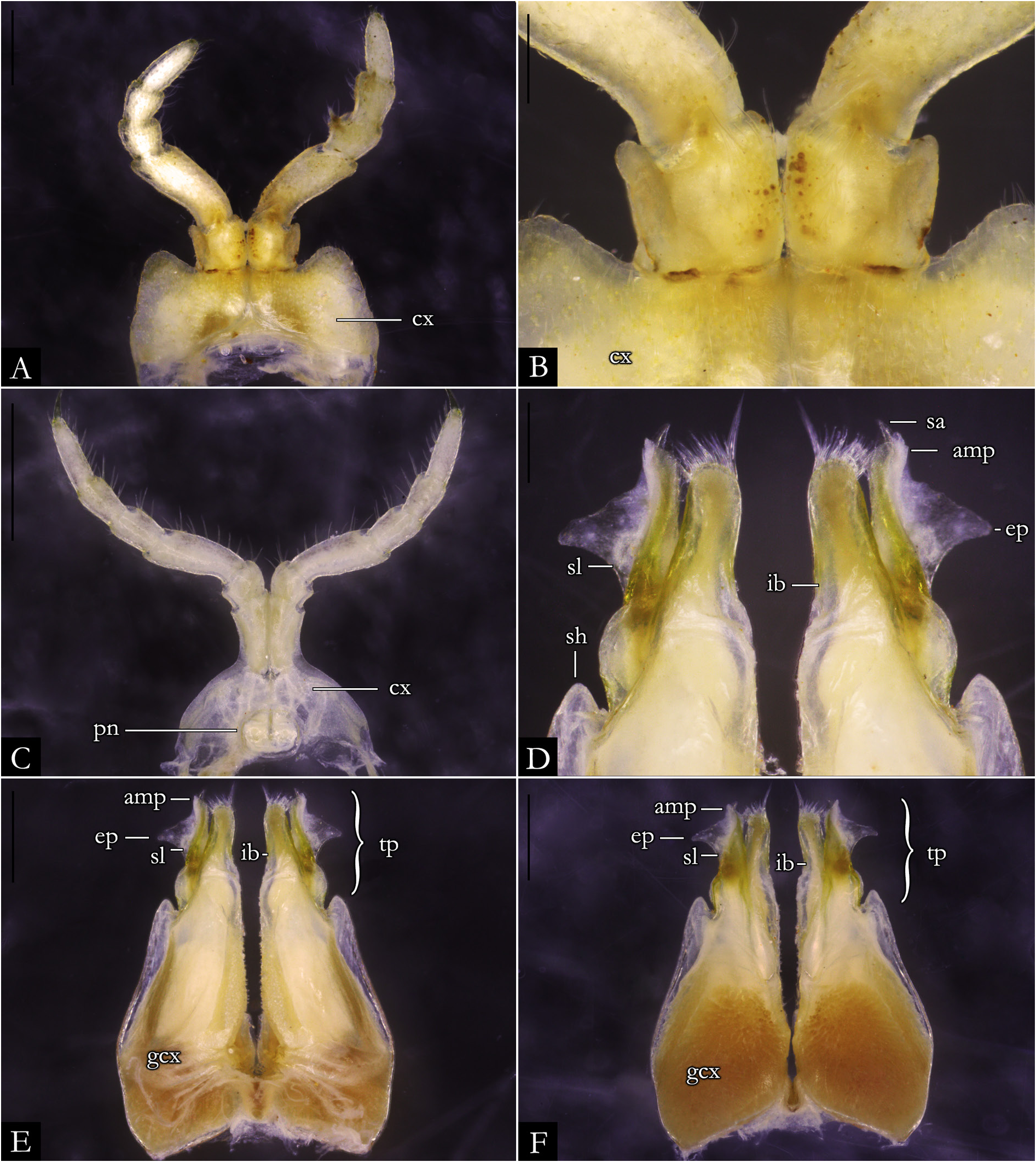

GNATHOCHILARIUM ( Figs 19E–F View Fig , 167–176 View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig ). Mentum pentagonal, males with medial depression deeply invaginated; paired projections observed in males of P. bucculenta sp. nov., and long setae in males of P. morettii sp. nov. and P. parvula . Promentum subtriangular, setose, with transverse suture separating it from mentum and a longitudinal suture separating promentum into two equal halves. Lamellae linguales with scattered setae surrounding central pads. Stipes slightly S-shaped, males of some species with distal region swollen ( Fig. 108C View Fig ); number of distal setae variable, stipital spurs absent; with proximal projections bearing setae in males of P. granulata sp. nov. ( Figs 175A View Fig , 198B) and P. callipyge ( Fig. 168D View Fig ).

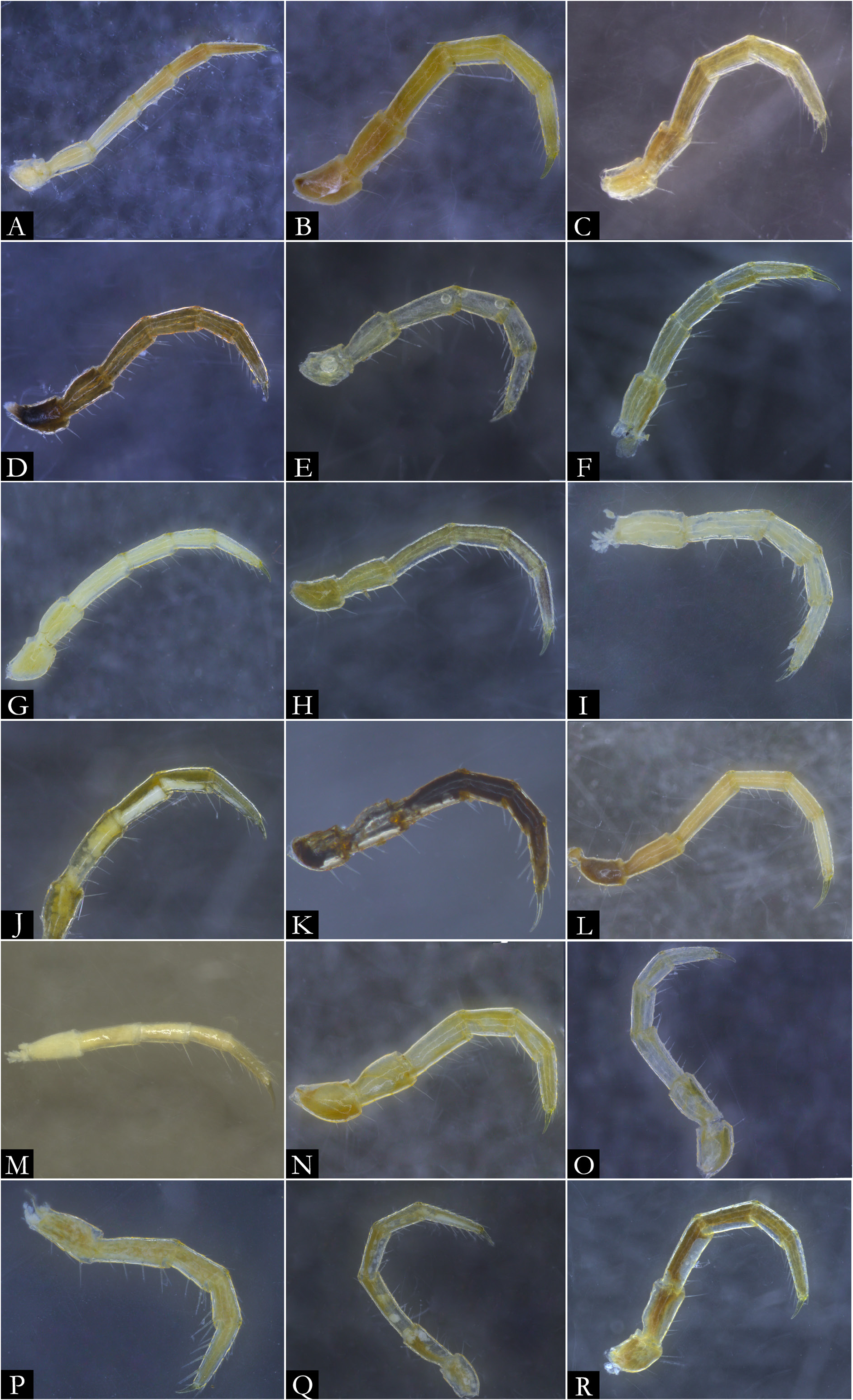

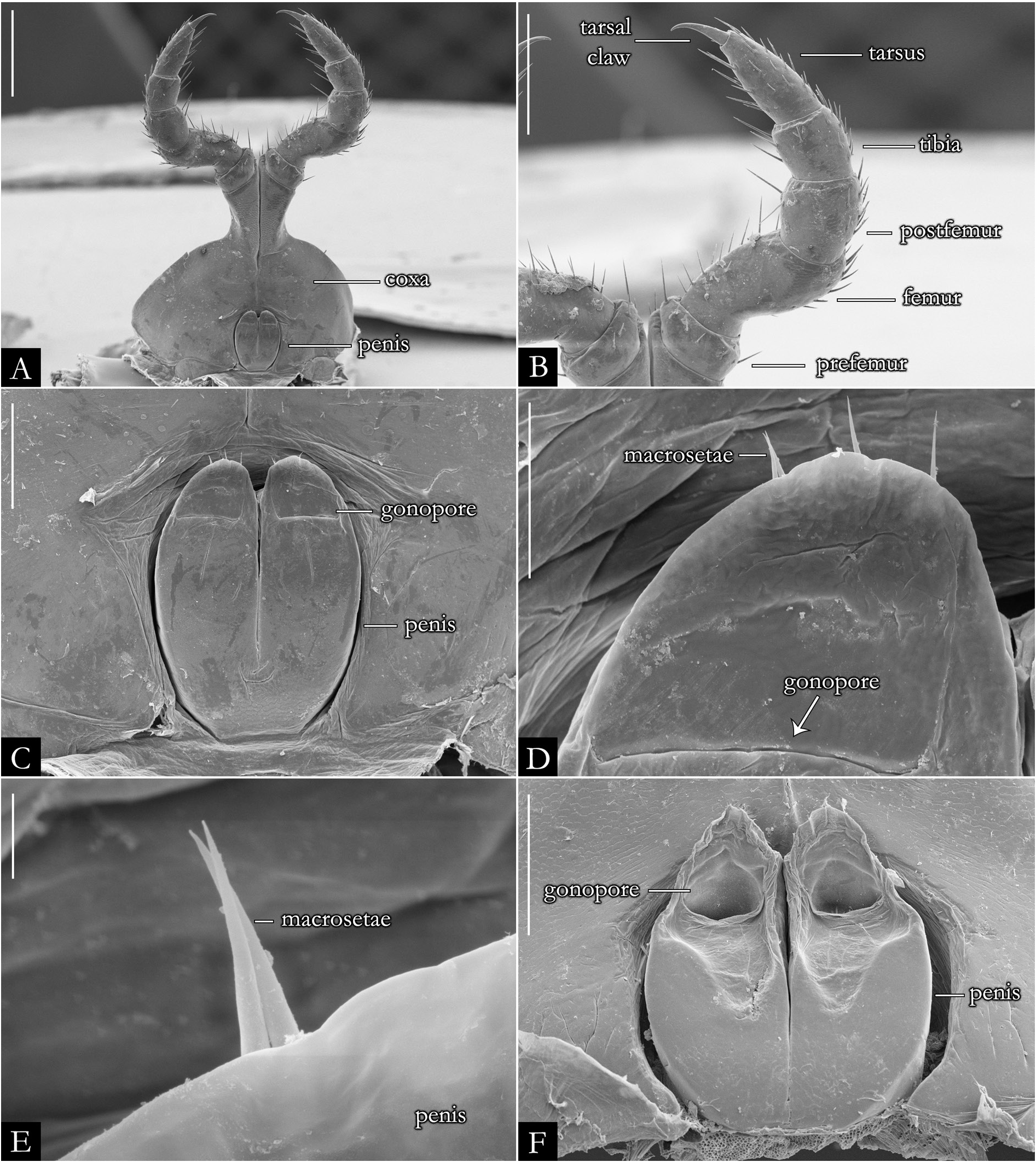

BODY RINGS. Collum with lateral lobes broadly rounded, densely striated ( Fig. 19C View Fig ); in some species, the lobes are strongly curved ectad ( Fig. 66A View Fig ). Following body rings very faintly constricted between prozonite and metazonite ( Figs 26A–B View Fig , 27A View Fig ); prozonites smooth; metazonites laterally with transverse striae below ozopore ( Fig. 26C View Fig ), in some species metazonites are strongly granulated ( Fig. 26D View Fig ). Anterior sternites subrectangular; slightly curved medially ( Figs 25A–B View Fig , 167–176 View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig ), in some species with transverse striae. Posterior sternites elliptical ( Fig. 25A–B View Fig ). Spiracles positioned proximally ( Fig. 25C–F View Fig ). Ozopore positioned at midlength of metazonite ( Figs 26A–B, E View Fig , 27A View Fig ), ozadene oval ( Fig. 27C View Fig ). Epiproct with rounded tip ( Fig. 28A, C View Fig ); with subtriangular process in P. buhrnheimi and P. granulata sp. nov. ( Figs 28D View Fig , 53B View Fig , 54 View Fig , 153B View Fig ). Paraproct with small setae on distal margin ( Fig. 28 View Fig ); with projections bearing setae in P. alegrensis ( Figs 44B View Fig , 202C). Hypoproct subrectangular ( Fig. 28A– B View Fig ). Midbody legs as long as half body diameter; without ventral pads; femur elongated. Prefemur, femur, postfemur, and tibia with long setae on mesal region ( Figs 29A–D View Fig , 165–166 View Fig View Fig ); tarsus densely setose ( Fig. 29A–D View Fig ), with tarsal claw ( Fig. 29E View Fig ).

FIRST LEG-PAIR OF MALES. Coxae elongated and setose, ranging from subtriangular ( Fig. 30A View Fig ) to subrectangular shape ( Fig. 30B View Fig ), with the base slightly arched; prefemoral process subcylindrical in most species ( Fig. 30A–D View Fig ), hexagonal in P. erikae ( Fig. 30F View Fig ) or absent in P. anapophysis Fontanetti, 1996 ( Fig. 49A–B View Fig ); densely setose along entire extension or up to median region; remaining podomeres with setae along the mesal region. Tarsal claw present.

SECOND LEG-PAIR OF MALES. Coxae fused basally, only distally paired ( Fig. 31A View Fig ); large, rounded or subrectangular-shaped; penis located at the proximal region, rounded ( Fig. 31C, F View Fig ); penial bases fused, extended basally in some species ( Fig. 31C View Fig ). Gonopore positioned distally, with short apical setae ( Fig. 31C–F View Fig ). Prefemur compressed dorsoventrally; remaining podomeres setose, with long setae on the mesal region ( Fig. 31B View Fig ); tarsal claw present.

SECOND LEG-PAIR OF FEMALES. Coxae fused basally; large, subrectangular-shaped ( Fig. 39A View Fig ); vulvar sacs large, located basally in anal view ( Fig. 39B–C View Fig ). Prefemur compressed dorsoventrally; remaining podomeres densely setose, with setae on the mesal region ( Fig. 39C View Fig ); tarsal claw present.

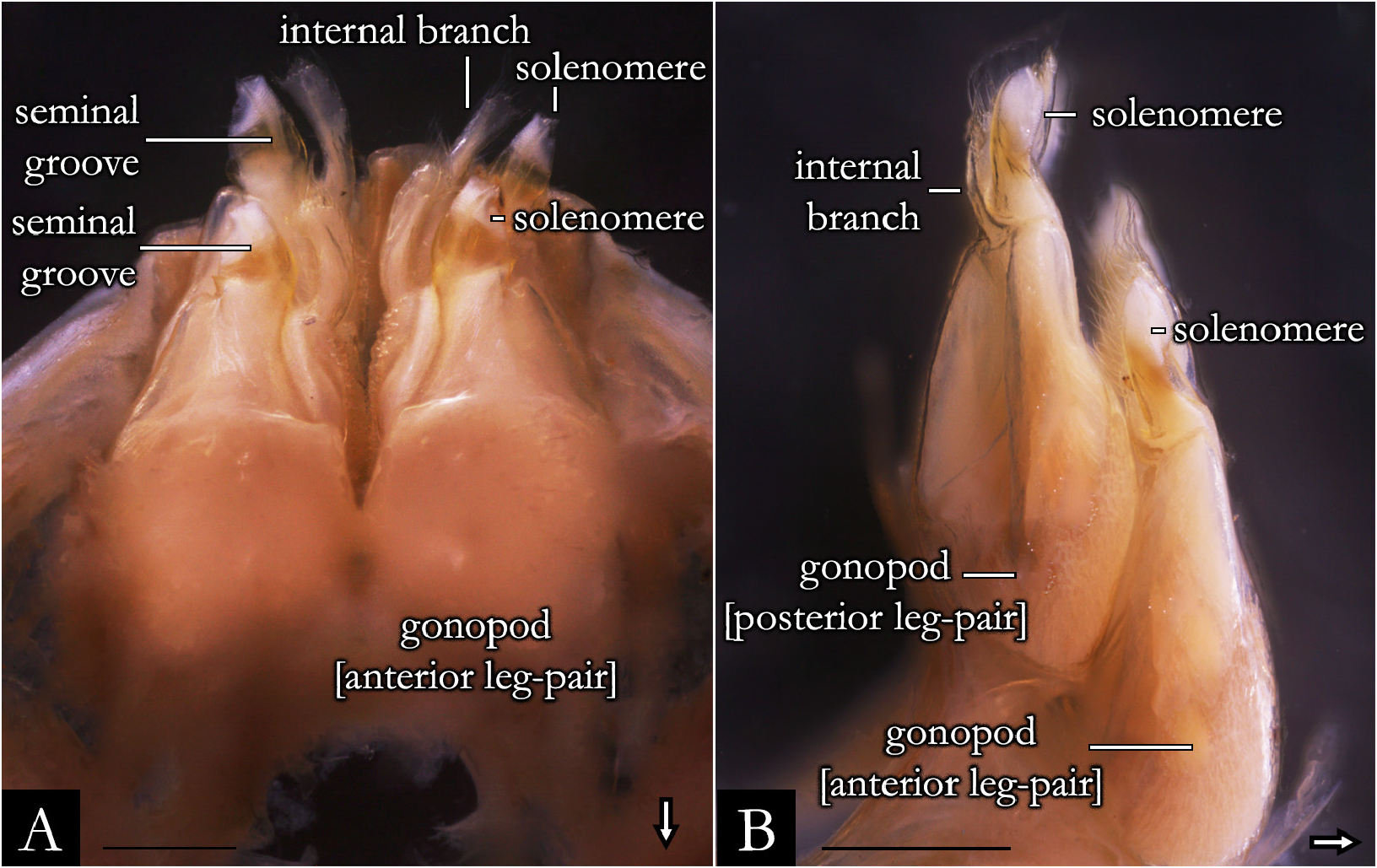

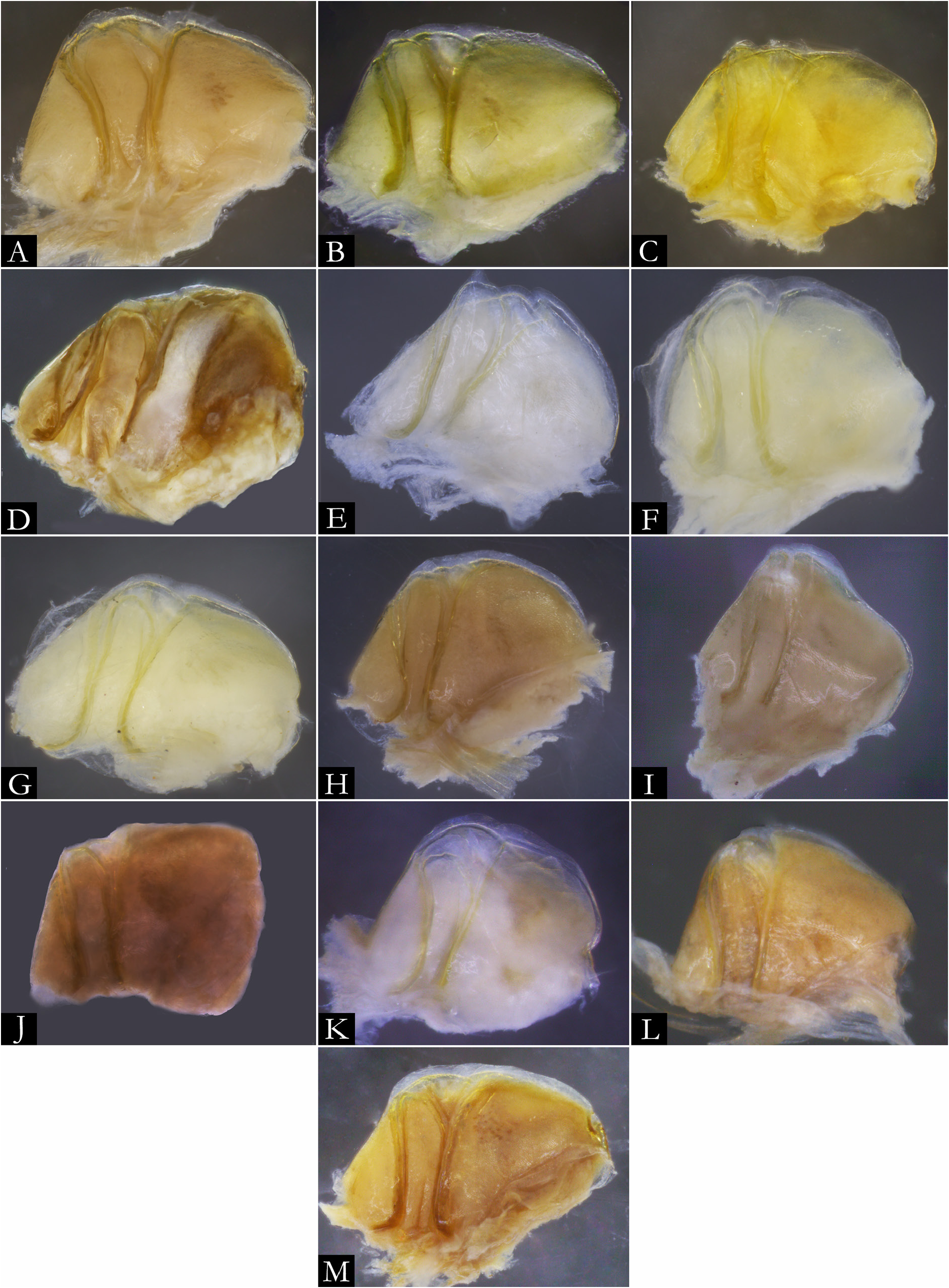

GONOPODS ( Figs 2 View Fig , 32–36 View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig , 38 View Fig ). Gonocoxa elongated, twice as long as telopodite; with base slightly arched; antero-posteriorly flattened; with rows of papillae positioned mesally. A large cavity located mesally on gonocoxa ( Fig. 32A–B View Fig ); with globular projection bearing setae ( Fig. 32D–F View Fig ); seminal groove curved, arising medially on mesal cavity and terminating apically on the seminal apophysis. Shoulder of gonocoxa positioned apically, present in most species. Gonopods distally divided into telopodite and internal branch ( Fig. 35A, C, E View Fig ). Telopodite separated from gonocoxa by shallow furrow; trunk of telopodite glabrous; with rounded laterad projection in some species. Solenomere with squamous surface, rounded apically, without or with subtriangular processes: apicomesal, ectal, and medial ( Figs 35 View Fig , 36A– C View Fig , 217); form, length, and position of these processes are variable in most species. Seminal apophysis located at mesal, medial or ectal portion on solenomere. Internal branch located at the base of telopodite, with setae marginally or apically; the form and length of the branch is variable, in some species it is narrow ( Fig. 35A View Fig ), swollen apically ( Fig. 35C View Fig ) or with a horizontal plate ( Fig. 222E). Some species with internal branch twisted 180° ( Fig. 222D) and with distal projection ( Fig. 222F).

VULVAE ( Figs 40 View Fig , 177–179 View Fig View Fig View Fig ). Vulvae embedded behind second leg-pair ( Fig. 32A–C View Fig ). Bursa subtriangular; glabrous ( Fig. 32D–F View Fig ). Internal valve subtriangular; connected with opposite internal valve only distally. Operculum narrow; situated laterally. External valve wide; subtriangular.

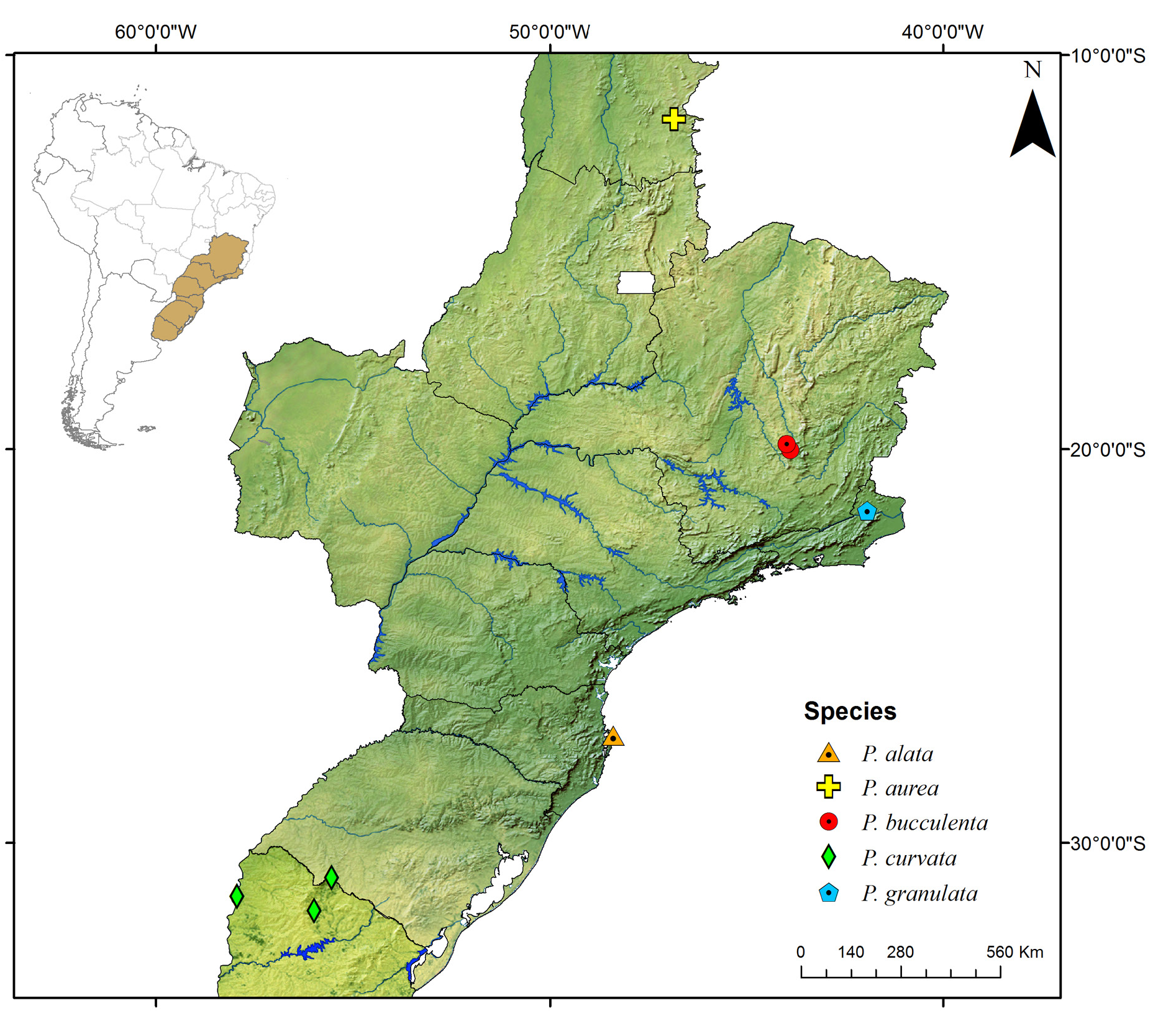

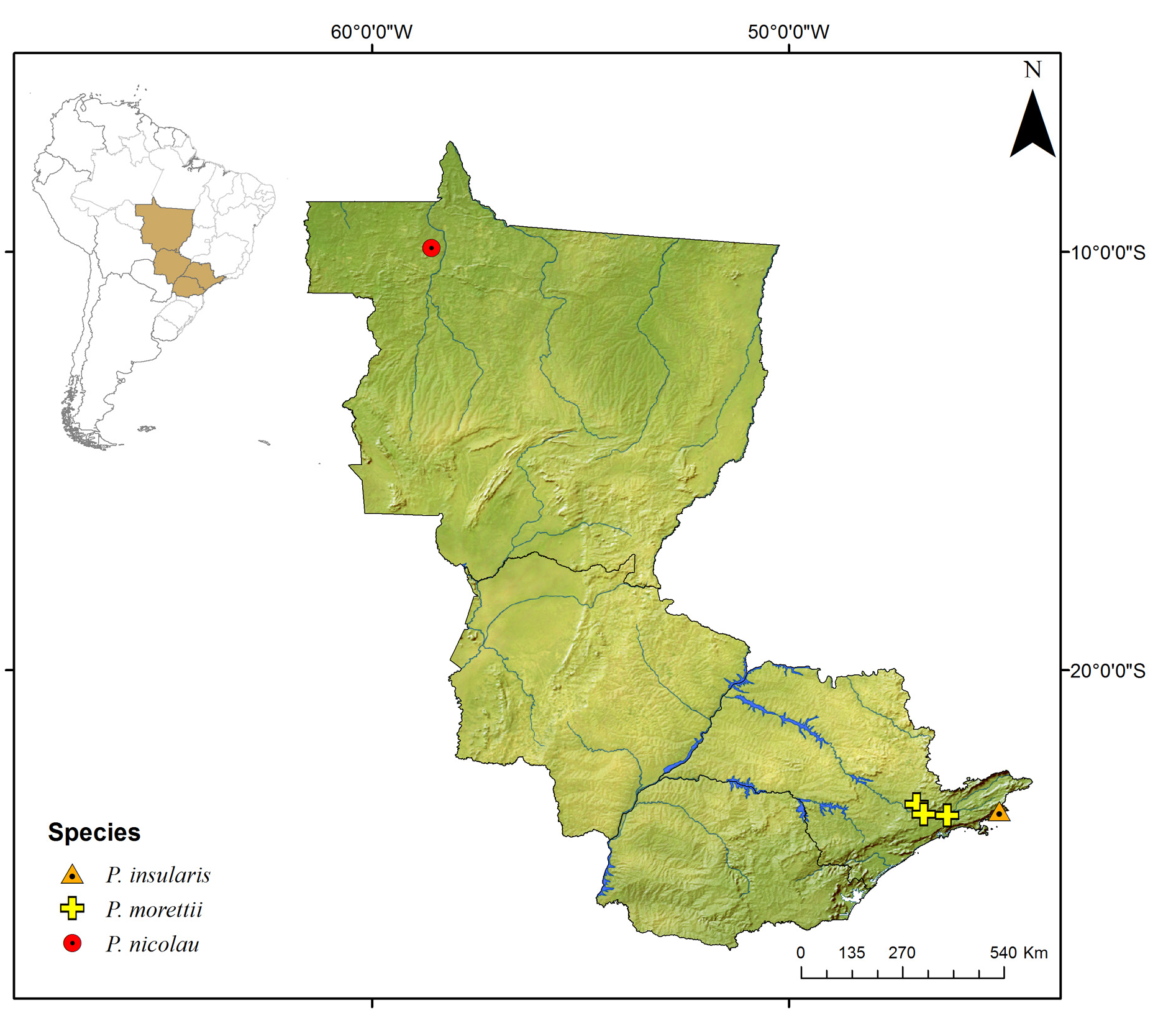

Distribution

Known only from the South American continent, ranging from French Guiana ( P. rugosetta ) down to southern Argentina ( P. patagonica Brölemann, 1902 ). Despite the wide distribution of the genus throughout the Chacoan biogeographic subregion (sensu Morrone 2014) ( Fig. 13 View Fig ), most of the species are narrowly distributed, often known only from the type locality ( Figs 180–191 View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig ).

Taxonomic notes

For some species described by Silvestri between the years 1895–1902 and collected by Alfredo Borelli in surrounding areas from the rivers Apa and La Plata, the type material was not found in collections where they were supposedly deposited. The same situation has been noted in other millipedes groups (for instance, Chelodesmidae Cook, 1895 , Paradoxosomatidae Daday, 1889 , Spirostreptidae ) and centipedes (Geophilomorpha Pocock, 1895) ( Jeekel 1965; Hoffman 1981, 1982; Krabbe 1982; Pena-Barbosa et al. 2013; Calvanese et al. 2019). A list of species described by Silvestri with their respective repositories was compiled by Viggiani (1973), although some species of Pseudonannolene were not listed by the author.

Ecological remarks

The biology of species of Pseudonannolene is poorly known, with some information restricted to species regarded as agricultural pests or cave-dwelling ( Schubart 1942, 1944, 1945a, 1947, 1949, 1958, 1960; Bock & Lordello 1952; Lordello 1954; Freitas et al. 2004; Iniesta & Ferreira 2013a). The available data on the phenology of species suggest that they tend to have a predilection to warm and humid periods, varying from a subtropical climate to tropical in the Chacoan subregion ( Fig. 13 View Fig ).

The species P. paulista Brölemann, 1902 and P. tricolor have been reported to feed on potato ( Solanum tuberosum L.), melon ( Cucumis melo L.), and beet ( Beta spp. L.) (Bock & Lordello 1952; Lordello 1954). In addition to P. ophiiulus Schubart, 1944 , these species have been also observed in second-growth forests, Eucalyptus spp. and Musa spp. , and in open areas with a predominance of shrub species ( Schubart 1944, 1945a). The species P. leucomelas has been recorded only from growing areas in northwestern Mato Grosso, Brazil ( Schubart 1944), while P. leucocephalus Schubart, 1944 , P. silvestris Schubart, 1944 , and P. urbica Schubart, 1945 have been found in any area with availability of organic deposits ( Schubart 1944, 1945a). The species P. alegrensis , P. leucocephalus , P. ophiiulus , P. paulista , P. silvestris , P. tricolor , and P. urbica are also reported in man-made and disturbed habitats such as houses, gardens, farms, and roadsides ( Silvestri 1897c; Schubart 1944, 1945a, 1949; Bock & Lordello 1952).

Most species of Pseudonannolene are found in outcrops of limestone rocks ( Trajano 1987; Trajano & Gnaspini-Netto 1991; Pinto-da-Rocha 1995; Fontanetti 1996; Trajano et al. 2000; Freitas et al. 2004; Iniesta & Ferreira 2014; Gallo & Bichuette 2019). The species P. ambuatinga , P. lundi Iniesta & Ferreira, 2015 , and P. spelaea are restricted to caves, presenting troglomorphisms such as depigmentation and body size reduction ( Iniesta & Ferreira 2013 a, 2015). The troglophilic species P. microzoporus , P. robsoni , and P. tocaiensis Fontanetti, 1996 have been found near vegetal debris (for instance, rotten trunks and litter) or guano of Desmodus rotundus (Geoffroy, 1810) (Chiroptera) inside caves, while P. robsoni , P. leopoldoi Iniesta & Ferreira, 2014 , and P. callipyge Brölemann, 1902 ( Fig. 17B–C View Fig ) have been commonly observed feeding on fungi and organic debris in aphotic zones and cave entrances.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Cambalidea |

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Pseudonannoleninae |

Pseudonannolene Silvestri, 1895

| Iniesta, Luiz Felipe Moretti, Bouzan, Rodrigo Salvador & Brescovit, Antonio Domingos 2023 |

Pseudonannolene typica

| Silvestri F. 1896: 170 |

Pseudonannolene

| Iniesta L. F. M. & Enghoff H. & Brescovit A. D. & Bouzan R. S. 2020: 5 |

| Hollier J. & Schiller E. & Akkari N. 2017: 218 |

| Shelley R. M. & Golovatch S. I. 2015: 7 |

| Iniesta L. F. & Ferreira R. L. 2013: 92 |

| Golovatch S. I. & Hoffman R. L. & Adis J. & Marques A. D. & Raizer J. & Silva F. H. O. & Ribeiro R. A. K. & Silva J. L. & Pinheiro T. G. 2005: 279 |

| Hoffman R. L. & Golovatch, S. I. & Adis J. & de Morais J. W. 1996: 14 |

| Hoffman R. L. & Florez E. 1995: 116 |

| Mauries J-P. 1987: 170 |

| Mauries J-P. 1983: 250 |

| Hoffman R. L. 1980: 91 |

| Mauries J-P. 1977: 248 |

| Verhoeff K. W. 1943: 269 |

| Brolemann H. W. 1929: 7 |

| Attems C. 1926: 206 |

| Carl J. 1914: 855 |

| Carl J. 1913: 174 |

| Brolemann H. W. 1902: 120 |

| Silvestri F. 1897: 651 |

| Silvestri F. 1896: 170 |

| Silvestri F. 1895: 7 |

| Cook O. F. 1895: 6 |