Neonesidea gerda ( Benson and Coleman, 1963 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4903.4.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D8AA9035-EB27-4F50-9246-B5450D71F3E2 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4434579 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F88789-847A-FFF0-FF0C-2943AD5C9931 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Neonesidea gerda ( Benson and Coleman, 1963 ) |

| status |

|

Neonesidea gerda ( Benson and Coleman, 1963) View in CoL

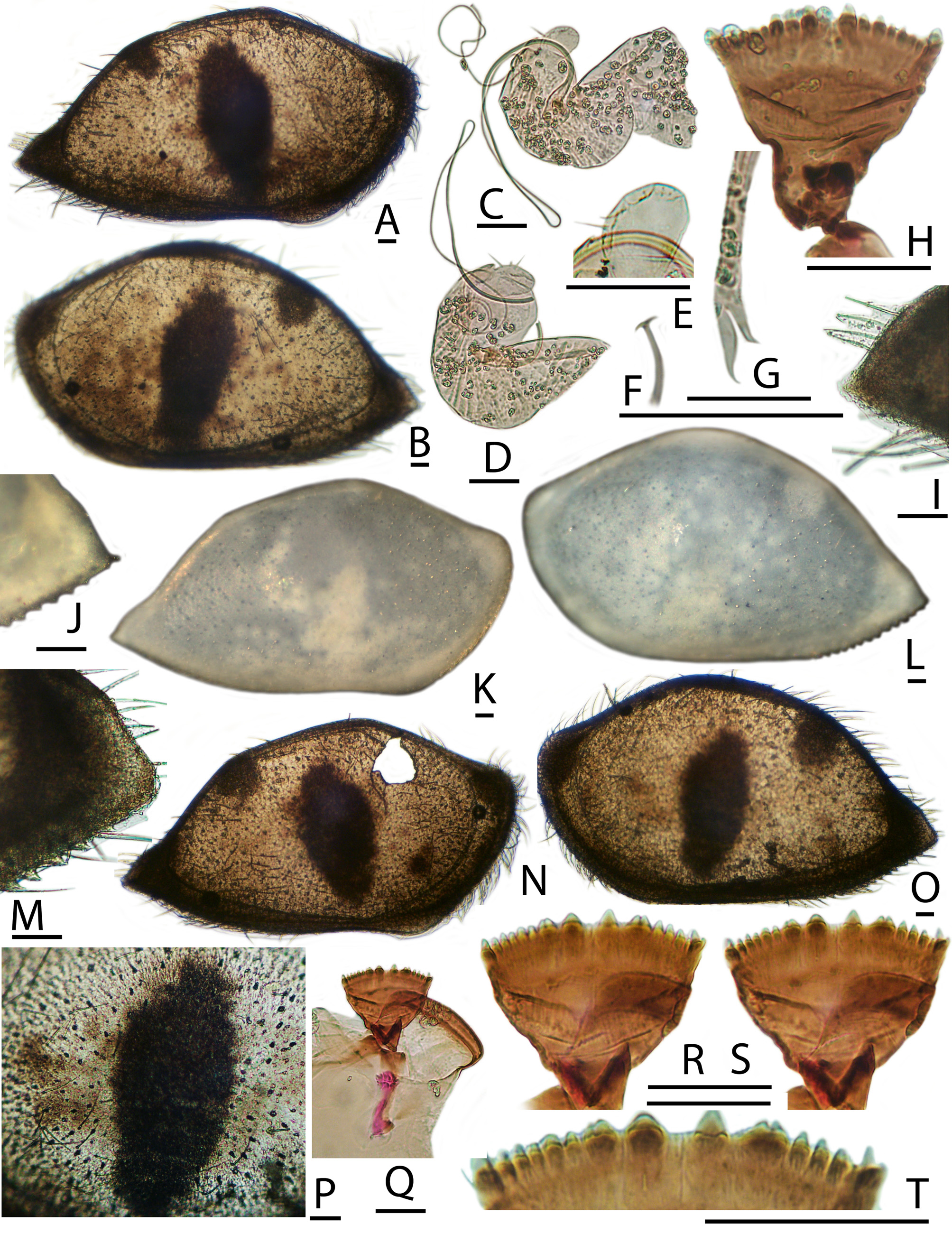

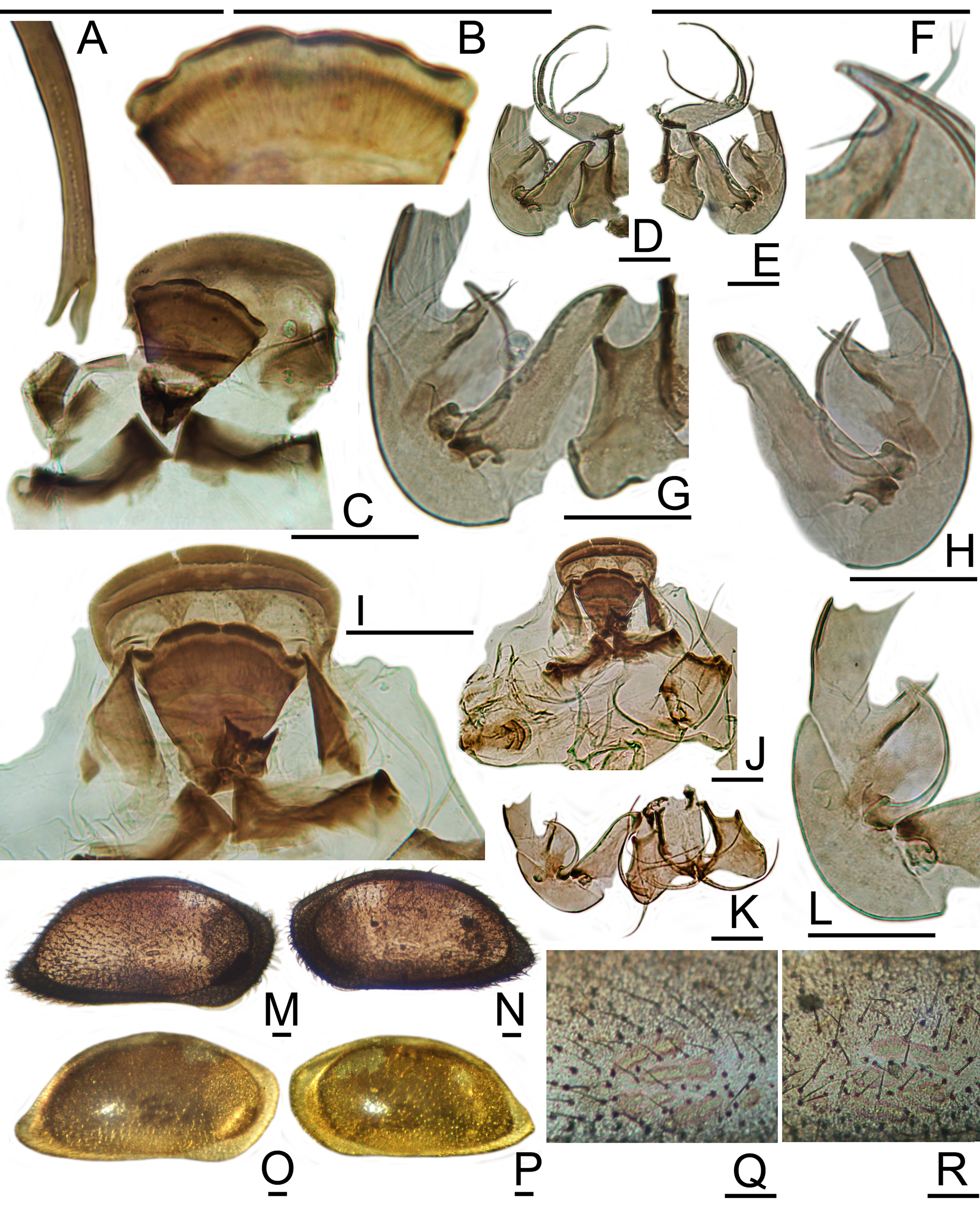

( Figures 8 View FIGURE 8 M–R, 9A–N, 10A–J, 11A–H; Graph 4)

? 1960 Bairdia crosskeyana Brady. —Puri, p. 130, Pl. 6, figs. 11–12.

1962 Bairdia cf. B. crosskeyana Brady. —Benda & Puri, Pl. 5, figs. 12–13.

1963 Bairdia gerda sp nov: 19, Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 , Pl. 1, figs. 14–16.

1966 Bairdia gerda Benson and Coleman. —Baker & Hulings, p. 114, Pl. I, fig. 17.

1966 Bairdia gerda Benson and Coleman. —Benson, p. 746 [designation of lectotype].

1967a Bairdia crosskeyana Brady. —Hulings, Table 1.

1967b Bairdia gerda Benson and Coleman. —Hulings, p. 637, Figs. 2a View FIGURE 2 , 3a View FIGURE 3 .

1969 Neonesidea gerda (Benson & Coleman) .—Maddocks, p.24 (part) [not Figs. 7 View FIGURE 7 A–K, which are N. longisetosa ]. 1978 Neonesidea sp. cf. N. gerda (Benson & Coleman) .—Kontrovitz, p. 139, Pl. 1, fig. 8 [juvenile].

1982 Neonesidea longisetosa (Brady) .—Krutak, p. 269, Pl. 5, figs. 1–5, Table 2.

1990 Bairdia gerda Benson and Coleman. —Lyon, p. D17, Pl. 1, fig. 1.

? 1990 Bairdia cf. B. longisetosa Brady. —Machain-Castillo, Table 2.

? 1992 Bairdia longisetosa Brady. —Machain-Castillo & Gio-Argáez, Appendix I.

partim 2009 Neonesidea longisetosa (Brady) .—Maddocks et al., p. 888.

Material. One living female from the West Coast of Florida off Tampa. Numerous subfossil specimens in sediment samples from the Florida Keys, the Flower Garden banks, Stetson Bank, and slide “ Cuba 3.” Photographs of subfossil specimens collected at OGMEX I station O- 8 in the Bay of Campeche taken by Ana-Maria Perez-Guzman (see also Machain-Castillo 1990).

Dimensions: Female specimen 2397F, LVL 0.833 mm, LVH 0.510 mm. The following dimensions were reported for the lectotype carapace: L 0.91 mm, H 0.53mm, W 0.44 mm ( Benson & Coleman 1963, Pl. 1, figs. 14–16; Benson 1966, p. 746). The dimensions reported for three specimens from Tortugas (USNM 88864) and the Bahamas (USNM 121258, 121259), which were misidentified as M. gerda by Maddocks (1969, p. 24), fall within the lower part of the range for N. longisetosa . The specimen illustrated by Lyon (1990) is a juvenile. See also Graph 4.

Supplemental Description: Most of the features mentioned in the description of N. gerda by Benson & Coleman (1963) are shared by most species in the N. schulzi species-group (informal). The LV lateral outline is higharched, with a distinctly peaked anterodorsal angle. The mid-dorsal margin slopes continuously to a subtle posterodorsal angle, which is rounded to indistinct. The posterior angle is acute, obliquely caudate, and located at approximately 17% of height. The anterodorsal margin is remarkably straight, meeting the anterior margin at a well-marked anterior angle. The anteroventral margin is sharply oblique and nearly straight. The ventral margin is straight and rises only slightly to the posterior angle. The RV lateral outline is more angulate, with more distinctly marked anterodorsal and posterodorsal angles, nearly straight mid-dorsal and anteroventral segments, and a more sinuous ventral margin, which rises to a more acute posterior angle.

Valves of recently-dead individuals are perfectly smooth with a highly polished sheen, translucent, light gray with a visible microcrystalline fabric, dotted by white NPC and AMS. Valves of longer-dead individuals are less transparent, becoming milky white. The patch pattern consists of a vertical oblong, located in front of and across the anterior half of the AMS. Smaller, less distinct opaque patches are located in the anterodorsal angle (most visible in the LV) and the posterior angle, but not at the posterodorsal angle. There are fairly numerous, rather thick, golden carapace sensilla, none of which are especially long. A row of enlarged pores for the plumose sensilla is located just dorsal to the caudal process.

Well-conserved LV have about nine very short, curved, posteroventral marginal denticles, which arise outside of and protect the selvage. These are abraded and not distinguishable in many subfossil valves. On a few of the bestconserved RV, a very narrow, incipient marginal frill is barely visible outside the selvage along the posteroventral margin. There are no anteromarginal denticles or frills on either valve.

The hemipenis of N. gerda has a moderately long, irregularly arcuate to nearly straight copulatory tube, which arises near the base of the median segment. The tube tapers abruptly and is thin-walled for much of its length. Distally it bifurcates or trifurcates into delicate threads. The terminal segment has a rounded margin and a mushroomshaped aesthetasc, around which is wrapped a short, half-cylindrical lamella. An opposing, shorter, half-cylindrical lamella has a thickened, wrinkled, irregular edge.

The plate of N. gerda has a symmetrical row of about six low-conical to sub-pyramidal teeth along the posterior margin, which project dorsally and posteriorly. They are somewhat larger medially and decrease a little in size laterally. Large, multilobate corner teeth are set apart from the medial teeth by a lateral gap, within which one or two tiny teeth are visible. The anterolateral scrolls are well developed. The posteroventral bracket is a symmetrical, U-shaped wall, with sharp horns projecting posterolaterally and multiple rounded tubercles along the anterior edge.

Remarks: Syntype specimens of N. gerda from Florida Bay were examined in 1965–1966, but not measured, and no soft parts were available. Subfossil assemblages from the Bahamas were not available at that time, and no reference material was available for N. longisetosa . For these reasons, Maddocks (1969) interpreted N. gerda as morphologically variable with a broad geographic range.

Maddocks (1969) suggested that N. gerda might turn out to be a synonym of N. longisetosa ( Brady, 1902) , and this erroneous prediction has been widely accepted ( Teeter 1975; Krutak 1982; Bold 1989; Krutak & Gio-Argaez 1994; Meireles et al. 2014A,B). The two species are fairly similar in appearance but differ in details of the hemipenis. Here, it is demonstrated that subfossil populations of the two species are distinguishable by the carapace shapes and dimensions, although isolated valves may occasionally be difficult to assign. In lateral outline, each species displays sexual dimorphism as well as within-species variability. Adults of N. gerda are smaller than adults of N. longisetosa but larger than A-1 instars of the latter species.

It can now be established that the three specimens illustrated and measured by Maddocks (1969, p. 24, Figs. View FIGURE 7

7A–K; collected from Tortugas, Bimini and Andros, all misidentified as N. gerda ) belong to N. longisetosa . Her drawing of the copulatory appendage ( Fig. 7D View FIGURE 7 ) shows the setulose tip characteristic of N. longisetosa . Her drawings of the valves ( Figs. 7 View FIGURE 7 H–K) show a distinct posterodorsal opaque spot as well as an upcurved posterior angle, both of which are characteristic traits of N. longisetosa .

The original photographs and drawings provided for N. gerda ( Benson & Coleman, 1963, Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 , Pl. 1, figs. 14–16) portray well its angular shape and distinctive appearance. The ventral margin of N. gerda is more nearly straight than that of N. longisetosa (especially in the RV). The posterior angle is more acute and is located more ventrally, at about 17% of height (compared with approximately 33% of height in N. longisetosa ). The posteromarginal denticles and posterior spine are smaller and less conspicuous than in N. longisetosa . In dorsal view, N. gerda has the same thickness-to-length proportions as N. longisetosa , but N. gerda is more diamond-shaped, with nearly straight anterolateral and posterolateral margins and acutely pointed anterior and posterior ends.

N. gerda is similar to but consistently larger than N. omnivaga , which is common on the Bermuda Platform. N. gerda is a little higher in proportion to length, with a more gently arched dorsal margin, higher anterior angle, less distinct posterodorsal angle, and less acute posterior angle. The dorsal outline is more angulate than the curves illustrated for N. omnivaga , and the thoracic legs were said to have more elongate distal podomeres than N. omnivaga ( Maddocks & Iliffe, 1986, p. 45, Fig. 6–I View FIGURE 6 ). The male soft parts are unknown for N. omnivaga . N. gerda and N. longisetosa have not been seen in Bermuda.

N. gerda is not likely to be confused with N. caraionae n. sp., which is very much larger, has more nearly hexagonal outlines, and has an unusual hemipenis with an extraordinarily long copulatory tube.

The plate of the flapper valve may assist with the distinction of these four species, although poor preservation in dry specimens introduces uncertainties: N. gerda tends to have an even array of about three subconical to subpyramidal teeth on either side of the medial gap, of which the first two or all three teeth are nearly equal in breadth and prominence. N. omnivaga has a broader medial tooth, followed by about three narrower teeth, all of equal prominence. N. longisetosa has a very prominent medial tooth followed by about four much smaller teeth, with sharply triangular to subpyramidal shapes. N. caraionae has a larger medial tooth, and then about five smaller teeth on either side, all with conical shapes.

N. gerda has sometimes been confused with Neonesidea crosskeiana ( Brady, 1866) , which lives in the eastern Mediterranean. Another similar species is Neonesidea woodwardiana ( Brady, 1880) from the Fiji Islands. The lectotype specimens for both of these species were redescribed by Titterton, Whatley & Whittaker (2001), but the soft parts, morphometric trends, and geographic ranges of the living populations are unknown. The dimensions reported for “ Bairdia crosskeyana ” by Puri (1960, Pl. 6, figs. 11–12; from Molasses Reef, off Tavernier in the Florida Keys) are those of a juvenile (L. 0.726 mm, H 0.327 mm).

Distribution: Benson & Coleman (1963) described N. gerda as common to abundant along the West Coast of Florida from Florida Bay to northwest of Tampa, between latitudes 24 o 59.0’N and 28 o 17.4’N, in water depths ranging from 20 to 70 feet. Puri (1960) may have collected it from his station 6 (Molasses Reef, off Tavernier in the Florida Keys). Its range extends north to Cape Romano, in western Florida ( Benda & Puri 1962). Lyon (1990) reported it to be rare in inner sublittoral facies off the east coast of Florida as far north as 28 o 17’24”N. The reported fossil occurrence in the Pleistocene of South Florida is plausible ( Kontrovitz 1978).

Here, the range of N. gerda is extended west to Stetson Bank and the East and West Flower Gardens banks on the continental shelf of Texas in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico, and to the Vera Cruz-Anton Lizardo Reefs in the southwestern Gulf of Mexico. The reefs off Vera Cruz represent the westernmost extent of reef corals in the Gulf of Mexico. The ostracod ecology and diversity of the Vera Cruz reefs were analyzed by Krutak & Rickles (1979) and Krutak et al. (1980). The occurrence of N. gerda (identified by him as N. longisetosa ) is well documented by Krutak’s (1982) illustrations. The records of “ Bairdia cf. B. longisetosa ” in the Bay of Campeche ( Machain-Castillo 1990, Machain-Castillo & Gío-Argáez 1993, Maddocks et al. 2009) probably apply to N. gerda .

Lyon (1990) stated that N. gerda is restricted to the Caribbean (tropical) faunal province of Hazel (1970, see also Hulings 1967a). More specifically, it follows the “transition zone” delineated by Bold (1977, Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 ) between the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean faunas. Along the Florida Keys, it predominates in samples taken in the more restricted conditions of Florida Bay, but not in reef and open-marine settings (where N. longisetosa is more likely). N. gerda is consistently represented in carbonate sediments of pinnacle reefs in the northern and western Gulf of Mexico but never in siliciclastic sediments of the neighboring shelf. Whether it also occurs within the transition zone around the western, northern and eastern edges of the Yucatan Platform ( Palacios-Fest et al. 1983; Bold 1989; Machain-Castillo & Gio-Argaez 1992) cannot be established from the data at hand, because any such occurrences are likely to have been included with the records of N. longisetosa . The estimated dimensions of the carapace illustrated by Baker & Hulings from Puerto Rico (1966, Pl. I, fig. 17, identified by them as N. longisetosa ) are appropriate for N. gerda , but it is likely that specimens of N. longisetosa were also included under this designation. Isolated valves that are questionably identifiable as N. gerda have been seen in subfossil assemblages from coastal waters of Cuba and other Caribbean islands.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SuperFamily |

Bairdioidea |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |