Agelas wiedenmayeri Alcolado, 1984

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3794.3.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:51852298-F299-4392-9C89-A6FD14D3E1D0 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5691125 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F7DF34-C00E-FFC5-FF40-CF8BDCD6EFE9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Agelas wiedenmayeri Alcolado, 1984 |

| status |

|

Agelas wiedenmayeri Alcolado, 1984 View in CoL

Figs. 4 View FIGURE 4 , 15 View FIGURE 15 F

The species was named to honour Felix Wiedenmayer, palaeontology curator at the Basel Museum.

Agelas wiedenmayeri Alcolado, 1984: 11 View in CoL , Figs. 7 View FIGURE 7 B–C, 8B; 2002: 62; Humann 1992: 22, Fig. pag. 23; Gammill 1997: 86, Fig. 86; Assmann et al. 1999: 455 Assman 2000: 39, pl. 5, Fig. A; Mothes et al. 2007: 87; Díaz 2007: 56; Alcolado & Busutil 2002: 69; Zea et al. 2009.

Agelas schmidti View in CoL ; Wiedenmayer 1977: 130, Fig. 137, pl. 27 Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 (with further synonymy), Zea 1987: 210, Fig. 76, pl. 12 Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 (with further synonymy); Gammill 1997: 43, Fig. 42, 74; Erpenbeck et al. 2007: 1564; Muricy et al. 2008: 84, figs.; Rützler et al. 2009: 302.

? Agelas schmidti View in CoL ; Wintermann-Kilian & Kilian 1984: 132; Muricy et al. 2011: 39.

[Non: Agelas schmidti Wilson, 1902: 398 View in CoL (a valid species)].

Material and distribution. Holotype not examined, but see remarks below; deposited at the Instituto de Oceanología—Cuba, IdO–409, collected in Barlovento (La Habana), depth 13 m. There is a schizoholotype at the National Museum of Natural History ( USMN 39229). The material reviewed here includes (but is not restricted to) specimens from Belize (INV– POR 952), Rosario Islands (INV– POR 965), Bahamas (INV– POR 923), San Andres Island (INV– POR 978) and Santa Marta (INV– POR 987).

There are also reports from the Bahamas ( Gammill 1997; Zea et al. 2009), Florida Keys ( Gammill 1997; Assmann et al. 1999; Assmann 2000; Rützler et al. 2009; Zea et al. 2009), Dominican Republic ( Weil 2006), Guadeloupe ( Alcolado & Busutil 2012), Guajira in northern Colombia ( Díaz 2007), Los Roques ( Venezuela, observed by S. Zea) and Northern Brazil ( Mothes et al. 2007; Muricy et al. 2008). From the above, we consider A. wiedenmayeri a tropical northwestern Atlantic species, despite its apparent absence in Jamaica, Barbados and Curaçao. Wiedenmayer (1977) collected his specimens between 37 to 42 m in the Bahamas. Zea (1987) collected his specimens between 6 to 35 meters in Rosario Islands and Santa Marta, and Díaz (2007) from 50 m in northern Colombia. Our specimens were found from 10 m to 35 m in depth, abundant between 21– 22 m.

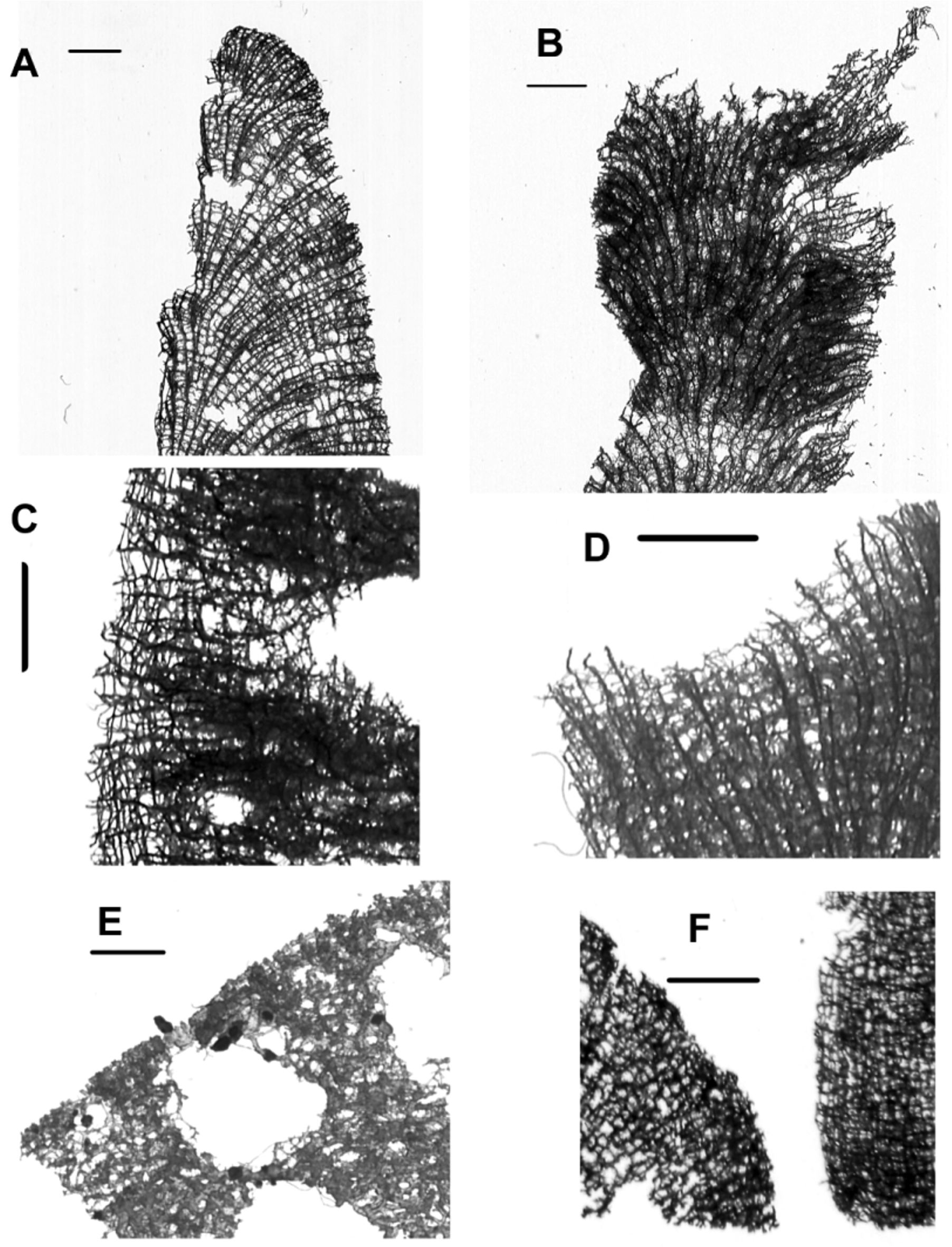

Description. This species usually forms clusters of cylindrical short tubes (4–15 cm, Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ), wider at their bases than their ends. Sometimes it is possible to find long (10–20 cm) solitary tubes slightly compressed, which maintain the diameter along all their length. The tubes have 1–3 cm of external diameter, and 0.5–2 cm of inner diameter. The walls are 2–5 mm thick. The tube clusters form a hollow, basal small body, which can be buried in rubble or filling spaces between ramose or foliose corals; solitary or branched tubes creep under rocks or corals, exposing only their apices. The ectosome colour in exposed areas is similar to A. dispar , dark brown, shaded areas and internal tissues are cream. Dry specimens maintain the color but it becomes reddish; older alcohol samples lose their colour, but the distinction of ectosome from choanosome is still possible. The pinacoderm, smooth and even, is similar to A. dispar .

There are two types of openings; the apical ones ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 A), circular or slightly elongated 0.5–2.5 cm wide, keyhole-like (see remarks); and circular oscules 1–4 mm wide, regularly scattered along the tubes, conspicuous in shaded areas, where they are sometimes occluded by a white “eardrum-like” membrane. Its consistency is spongy in life, harder when dry. The choanosome of the tube walls is not cavernous apart from some narrow (<4 mm) channels connected with the small oscules.

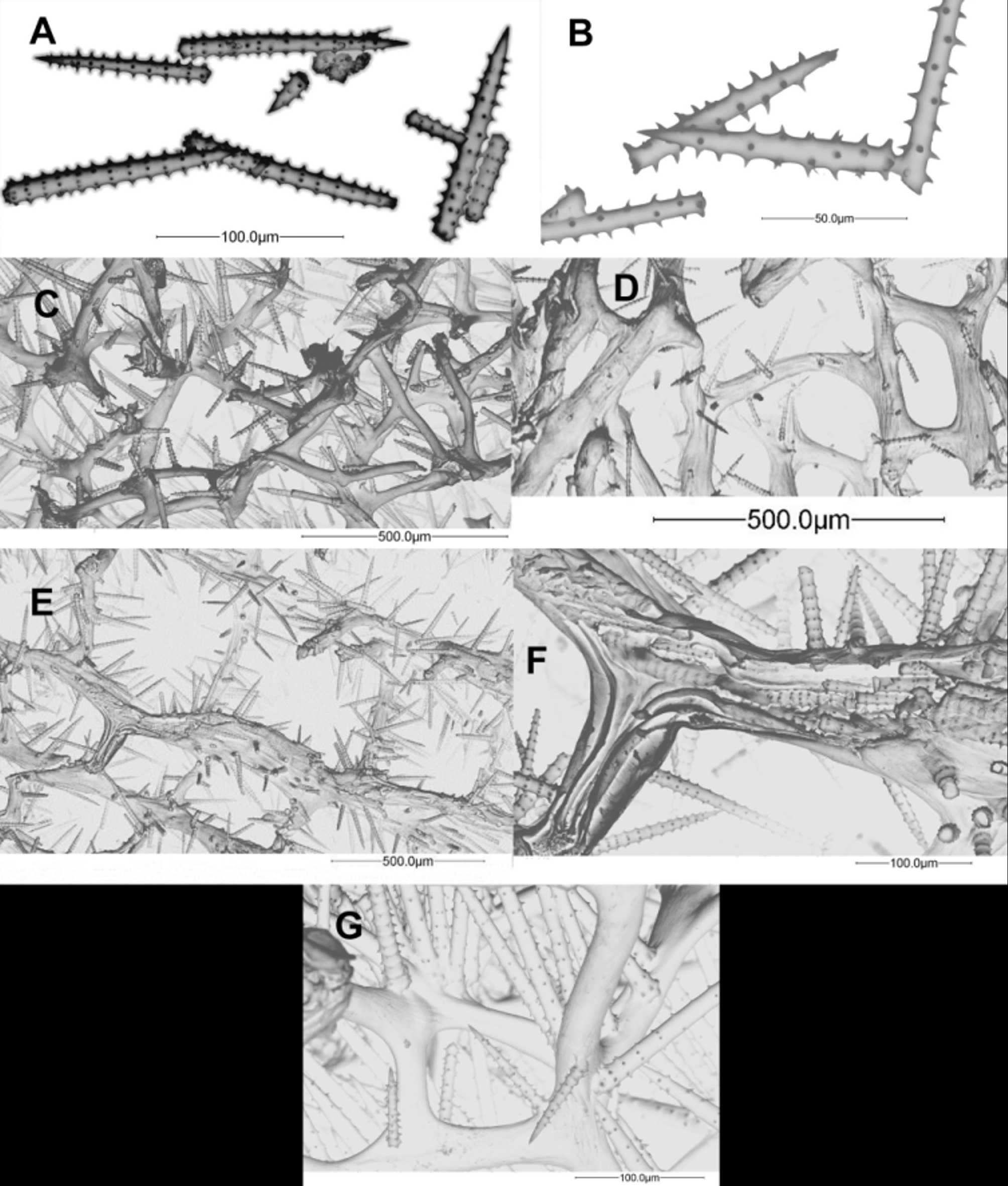

The primary fibres are more or less straight with 60–105 µm in diameter; they are echinated and cored by 1–6 spicules. Interconnecting secondary fibres are less echinated, 40–80 µm in diameter; tertiary fibres not present. The main fibres are oblique to the surface, radiating and ascending from the inner surface of the tubes to the external surface. The acanthostyles are curved but is not unusual to find some of them straight; the whorls, with 3–9 spines, more or less regularly spined and spaced at most geographical areas, are irregular at Santa Marta; length 72–288 (136±37.2) µm, width 4–15 (9±3) µm and 7–21 (12±2.6) whorls per spicule. Detailed lengths, widths and average number of whorls are shown in Table 2.

Remarks. Dr. P.M. Alcolado kindly checked several photographs, spicule/skeleton measurements and descriptions of our material and agreed with our identification. Dr. P.M. Alcolado also provided us with a small fragment in order to compare our material with his. Wiedenmayer (1977) description of A. schmidti does not match the holotype and original description of Wilson (1902), but match the holotype and description of A. wiedenmayeri (see also Alcolado 1984). We examined a spicule mount and several old and recent photographs of the holotype of A. schmidti and it is definitely a different species. Zea (1987) followed Wiedenmayer’s lead, as apparently did Muricy et al. (2008; 2011) and Rützler et al. (2009).

In Belize and the Bahamas this species appears as erect tube clusters ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 A, B), but in Rosario Islands ( Colombia) it occurs mainly as creeping solitary or sparsely branched tubes ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 D). In Santa Marta it forms clusters of tubes, but the tubes are long (15–20 cm), thin (1 cm), and the basal body is strongly reduced or absent. Only one solitary tube was found in San Andres Island ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 C). This species lives in low to medium waveexposed sites, usually in foliose coral or rubble habitat, or in crevices or under foliose corals in reef slopes. In Belize, it is common to find specimens with short tubes in remarkable similarity with A. dispar (see remarks above); however the absent or reduced short hollow body formed by coalescent tubes distinguish them.

Gammill (1997) distinguished two morphotypes of this species (using A. schmidti as its name), that often coexist, one with the tops of tubes flattened and another with more rounded tube tops, with the characteristic keyholelike oscules. Although we observed flat-topped tubes, we were not aware of consistent differences with rounded ones; Gammill’s (1997) hypothesis of these being separate species should be tested. Based on the results of our work and photographs, we believe the specimens under the name A. schmidti used in Erpenbeck et al. (2007) really correspond to A. wiedenmayeri .

The initial confusion with A. schmidti probably arose from a small note at the end of Wilson’s description (1902): “Schmidt (loc. cit) divides his Chalinopsis species into two groups, the one including solid forms ( Pachychalinopsis ), the other tubular forms (Siphochalinopsis). Of the latter group he had but a single specimen, which he mentions was 9 cm high, with a wall 3 mm thick, and with spicules like those of Chalinopsis (Agelas) . Schmidt thought it unnecessary to found [sic] a species name on such slight material. Schmidt’s specimen in the Museum of Comparative Zoology is essentially identical with mine, although the wall is thicker, color is dark brown, and the whorls of spines on the spicules are somewhat more distinct, the number in a whorl usually, exceeding four (6 to 8, about).” (Underlined is ours.)

Our hypothesis is that part of the Schmidt’s material to which Wilson referred is actually A. wiedenmayeri . But the real identity of those specimens at the Museum of Comparative Zoology still needs to be assessed. Wintermann-Kilian & Kilian (1984) material from Santa Marta ( Colombia) needs to be checked, as these authors did not mention colour, and it could belong to A. wiedenmayeri or it could be A. schmidti . The compilation of Brazilian records for A. schmidti by Muricy et al. (2011) needs to be revised as at least Muricy et al. (2008) probably belongs to A. wiedenmayeri on account of its brown color.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Agelas wiedenmayeri Alcolado, 1984

| Parra-Velandia, Fernando J., Zea, Sven & Van Soest, Rob W. M. 2014 |

Agelas wiedenmayeri

| Mothes 2007: 87 |

| Diaz 2007: 56 |

| Alcolado 2002: 69 |

| Assman 2000: 39 |

| Assmann 1999: 455 |

| Gammill 1997: 86 |

| Humann 1992: 22 |

| Alcolado 1984: 11 |

Agelas schmidti

| Muricy 2011: 39 |

| Wintermann-Kilian 1984: 132 |

Agelas schmidti

| Muricy 2008: 84 |

| Erpenbeck 2007: 1564 |

| Gammill 1997: 43 |

| Zea 1987: 210 |

| Wiedenmayer 1977: 130 |