Agelas dispar Duchassaing & Michelotti, 1864

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3794.3.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:51852298-F299-4392-9C89-A6FD14D3E1D0 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5691121 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F7DF34-C007-FFC1-FF40-CC03DD57EE58 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Agelas dispar Duchassaing & Michelotti, 1864 |

| status |

|

Agelas dispar Duchassaing & Michelotti, 1864 View in CoL

Figs. 1 View FIGURE 1 D, 2, 15C, 15E

Etymology from Latin, meaning dissimilar, different.

Agelas dispar Duchassaing & Michelotti, 1864: 76 View in CoL , pl. 15 Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 .

For synonymy and taxonomic treatment, see Wiedenmayer (1977: 128), Zea (1987: 207), and remarks herein. In addition:

Agelas dispar View in CoL ; Boury-Esnault 1973: 285, Fig. 45, pl. 1, Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 ; Solé-Cava et al. 1981: 131, Figs. 7 View FIGURE 7 , 20; Pulitzer-Finali 1986: 107, Fig. 32A; Lehnert 1993: 50, Figs. 22, 79–82 (but Figure 22 does not seem to match); Gammill 1997: 43, Figs. 41, 45, 50, 52; Lehnert & van Soest 1998: 81; 1999: 154; Assmann 2000: 38, pl. 6 (in part, brown morphotype only, Figs. B and C; Figs. A and D are A. sventres View in CoL ); Valderrama 2001: 49; Alcolado 2002: 61; Díaz 2005: 470; Collin et al. 2005: 650; Erpenbeck et al. 2007: 1564; Mothes et al. 2007: 85; Muricy et al. 2008: 82, figs.; Rützler et al. 2009: 302; Zea et al. 2009; Moraes 2011: 166, figs.; Muricy et al. 2011: 38; Alcolado & Busutil 2012: 69.

Agelas sparsus View in CoL ; de Laubenfels 1936: 73; Alcolado 1976: 4.

Agelas sparsus View in CoL var. clavaeformis ; Alcolado 1976: 4.

Agelas dispar View in CoL f. clavaeformis; Alcolado 2002: 61; Alcolado & Busutil 2012: 69.

Agelas View in CoL sp. 2; Pulitzer-Finali 1986: 113, Fig. 32G.

[Non: A. dispar View in CoL ; van Soest 1981: 10, 34; Alvarez & Díaz 1985: 81, Fig. 23; Green et al. 1986: 130, Figs. 5 View FIGURE 5 –6; Kobluk & van Soest 1989: 1216 (= Agelas sventres View in CoL ); Wintermann-Kilian & Kilian 1984: 132 (unknown identity)].

Material and distribution. Holotype ( ZMA – POR 607) examined at the Zoölogisch Museum Amsterdam, collected in Saint Martin. Duchassaing & Michelotti (1864) mention that this species is also present in Guadeloupe, St. Croix, St. Thomas and Vieques. There is no mention of depth. The material reviewed here includes (but is not restricted to) specimens from Barbados (INV– POR 919), Belize (INV– POR 948, 953), Rosario Islands (INV– POR 962; see also Zea 1987), San Andres Island (INV– POR 976; see also Zea 1987 from Old Providence), Jamaica (INV– POR 1002), and the Bahamas (INV– POR 824, 933). F. Parra-Velandia observed this species in Curaçao at the island shelf eastern border off Boca Tabla, and S. Zea also observed this species at La Parguera, SW Puerto Rico and Bocas del Toro, Panamá. At the ZMA collection there are specimens from Puerto Rico ( ZMA – POR 3318), St. Eustatius ( ZMA – POR 3955), Brazil ( ZMA – POR 17312) and Martinique ( ZMA – POR 3582).

Previous works (including accounts by Wiedenmayer 1977; Zea 1987) have reported the species also from the Gulf of Mexico (Rützler et al. 2009), Florida (Gammill 1998), the Bahamas ( Gammill 1997; Zea et al. 2009), Cuba ( Alcolado 1976; 2002), Dominican Republic ( Pulitzer-Finali 1986; Weil 2006), Virgin Islands, St. Martin, Guadeloupe ( Duchassaing & Michelotti 1864; Alcolado & Busutil 2002), other areas of Colombia (San Bernardo Islands, Urabá, see Valderrama 2001), and Panama (Díaz 2005; Collin et al. 2005). Also in several areas of continental Brazil (from the North region down south to Rio de Janeiro, Boury-Esnault 1973; Solé-Cava et al. 1981; Mothes et al. 2007; Muricy et al. 2008, 2011) and its oceanic islands (Atol das Rocas, Fernando de Noronha, Isla da Trindade; cf. Moraes 2011). It is absent from Santa Marta rocky and coral reefs, perhaps because of the upwelling there. From the above, we consider A. dispar a tropical western Atlantic species. Our specimens were found from 1.5 to 32 m in depth, abundant between 17 and 21 m.

Description. Typically massive ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 B), to round lobate ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 D), sometimes flabellate ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 F); height from 10 to 40 cm, diameter from 20 to 50 cm, width from 5 to 10 cm. The ectosome in exposed areas is dark brown, although in some areas (e.g., Puerto Rico) it could be light milky brown; shaded, unexposed areas and internal tissues are cream. Dry specimens maintain the colour somewhat but become greyish; older alcohol specimens usually lose some of their external colour but it is always darker and distinguishable from the choanosome. Pinacoderm is thin, strongly coloured, resting on spicule tufts; this species has a typically smooth surface, also in dry specimens. The “velvety potato” nickname by Wiedenmayer (1977) best fits its aspect. When the pinacoderm is contracted, it is possible to distinguish invaginations and sub-superficial channels.

Openings can be scattered key-holes, 4–6 mm wide and 2–5 cm long; irregularly circular, collared oscules 2–3 mm in diameter, sometimes clustered; and small regular circular oscules, 2–4 mm in diameter, aligned in rows, being punctures of pinacoderm-covered subdermal channels ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 B, 2F and 2G), which in flabellated specimens tend to occur in rows towards the outer edge, aligned perpendicular to it. Its consistency is spongy but firm; in life it is elastic more than hard, almost uncompressible when dry. The interior is cavernous but with dense walls separating caverns; it is punctured by primary canals 2–12 mm in diameter, from which secondary canals radiate, 150–1000 µm wide.

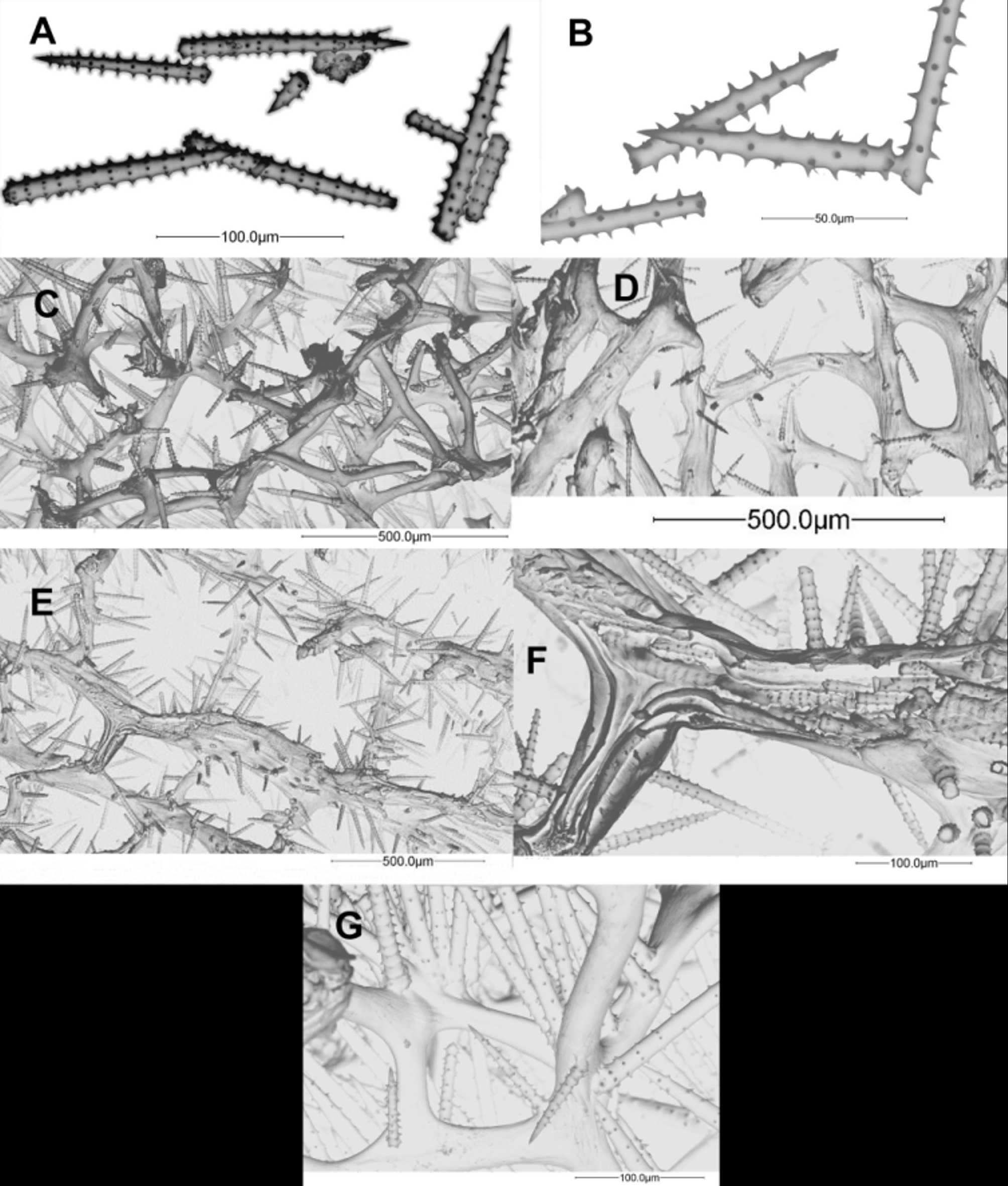

The skeleton is a regular and dense reticulation of spongin fibres; primary fibres long, more or less straight, cored (1–9 spicules per cross section) and echinated; diameters 25–132 µm. Secondary interconnecting fibres not cored and less echinated than primaries, 10–75 µm in diameter; tertiary fibres absent ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 H). Acanthostyles are usually slightly curved; whorls regularly spined and spaced, with 5–8 spines; length [minimum–maximum (mean ± SD)] 81–174 (125±19.3) µm, width 4–25 (9±3.2) µm and 7–16 (11±1.7) whorls per spicule. Detailed lengths, widths and average number of whorls are given in Table 2.

Species Locality Length (µm) Width (µm) Num. whorls

A. dispar Bahamas 94–160 (125±18.8) 4–7 (6±0.9) 8–13 (10±1.5) Barbados 107–170 (143±16.9) 8–13 (11±1.2) 10–15 (12±1.4) Belize 93–174 (131±16.9) 6–16 (11±2.2) 8–16 (11±1.6) Jamaica 82–129 (103±20.0) 4–25 (7±3.6) 7–15 (10±1.8) Rosario Islands 107–163 (132±16.0) 10–15 (12±1.5) 7–12 (10±1.1) San Andrés Island 84–150 (118±16.0) 4–10 (7±1.5) 7–14 (11±1.6)

A. cervicornis Bahamas 65–98 (83±9.7) 1–6 (4 ± 0.9) 7–12 (10±1.6) Jamaica 84–135 (103±13.4) 5–13 (8 ± 1.7) 6–16 (10±2.4)

A. wiedenmayeri Bahamas 73–111 (93±10.0) 4–8 (6±1.0) 7–14 (10±1.8) Belize 97–164 (131±15.9) 7–15 (12±2.1) 7–14 (10±1.5) Rosario Islands 113–227 (165±28.5) 7–14 (11±2.1) 11–16 (13±1.5) San Andrés Island 72–191 (131±29.1) 5–15 (9±2.9) 10–21 (14±2.5) Santa Marta 105–288 (168±42.8) 5–12 (9±1.7) 10–17 (13±1.8)

A. sceptrum Curacao 91–193 (135±27.8) 5–12 (9±1.8) 10–20 (14±2.7) Jamaica 78–228 (141±32.5) 5–12 (9±1.6) 7–26 (14±3.9) Rosario Islands 84–219 (138±38.0) 7–18 (12±2.9) 7–20 (11±2.5) San Andrés Island 78–249 (133±39.1) 6–14 (9±2.2) 7–22 (12±3.6)

A. dilatata Bahamas 75–160 (108±22.2) 4–8 (6±1.1) 9–18 (13±2.4)

A. conifera Bahamas 94–205 (129±22.6) 5–11 (8±1.2) 10–21 (14±2.6) Barbados 97–192 (142±26.6) 7–15 (11±2.6) 9–17 (12±2.1) Belize 72–187 (132±26.2) 6–16 (11±2.2) 6–19 (12±3.2) Curacao 102–163 (131±16.2) 3–11 (8±1.7) 10–16 (12±1.6)

A. tubulata Bahamas 72–182 (112±24.8) 5–10 (7±1.1) 8–19 (13±2.5) Jamaica 84–198 (114±23.7) 4–11 (6±1.5) 11–24 (15±3.0) San Andrés Island 82–193 (135±26.0) 4–14 (9±2.0) 8–19 (14±2.3) Santa Marta 82–165 (124±18.6) 7–12 (10±1.3) 10–18 (14±1.9)

A. repens Jamaica 88–268 (180±46.1) 3–13 (8±2.1) 9–23 (16±4.1)

......continued on the next page Species Locality Length (µm) Width (µm) Num. whorls

A. cerebrum Bahamas 72–167 (115±21.9) 3–10 (7±1.4) 8–20 (13±2.5)

A. clathrodes Bahamas 55–125 (93±17.2) 2–11 (5±1.9) 4–13 (10±2.1) Belize 66–284 (137±60.4) 5–17 (9±3.4) 5–23 (11±4.5) Jamaica 71–120 (97±14.1) 4–11 (8±1.3) 5–10 (8±1.2) Rosario Islands 82–191 (133±27.6) 5–15 (11±1.8) 5–15 (9±1.7) San Andres Island 73–127 (95±13.8) 5–9 (8±1.0) 6–9 (7±0.9) Santa Marta 74–126 (100±15.9) 6–12 (9±1.5) 9–13 (11±1.1)

A. schmidti Bahamas 62–163 (104±21.1) 2–5 (4±0.7) 5–14 (10±1.9) Barbados 56–210 (150±36.4) 6–13 (9±1.8) 7–22 (11±3.1) Curazao 43–157 (93±20.4) 4–10 (7±1.5) 4–14 (8±1.9) Jamaica 86–201 (125±27.4) 5–9 (7±0.8) 4–15 (9±1.9)

A. citrina Bahamas 111–212 (155±29.9) 6–10 (9±1.1) 9–19 (13±2.7) Barbados 98–286 (189±42.0) 4–20 (13±3.3) 9–19 (14±2.8) Belize 140–254 (196±42.0) 10–13 (12±0.9) 10–16 (13±1.9) Curacao 105–187 (132±21.3) 8–12 (10±1.0) 8–16 (11±1.9) Jamaica 88–199 (134±24.7) 5–10 (8±1.2) 6–14 (9±1.7) Rosario Islands 92–280 (181±49.8) 8–18 (13±2.4) 9–20 (14±3.0) San Andres Island 103–230 (142±35.6) 6–19 (12±3.1) 9–15 (12±2.3)

A. sventres Belize 86–168 (125±23.8) 4–13 (9±2.6) 7–11 (9±1.1) Rosario Islands 75–284 (127±46.4) 5–12 (8±2.3) 5–14 (9±1.6) Remarks. This species is typically present in sites with medium to high wave-exposure, but can be found in deep or calm waters too. From our field work we noticed that A. dispar occurs in areas of constantly warm waters, which could explain the absence of the species at Santa Marta and its scarcity in Curaçao, where seasonal upwelling occurs. E. Hajdu (pers. comm.) observed that this species in Ceara (NE Brazil) has a diameter of 1 m, but he states that, apart from their size, they are harder than A. dispar in other Brazilian areas, so their real identity needs to be confirmed.

Although the most common form is round lobate, in areas like Belize it could be easily confused with A. wiedenmayeri , also dark brown in color, due to the short, tapered fingers (lobes) that A. dispar develops when growing in high energy environments or in rubble and sand. The clear distinction comes from definite lack in A. dispar of an upper hole in the fingers, and the presence of a massive body below, attached to the bottom or filling crevices or holes. Instead, in A. wiedenmayeri , the massive body is absent or is reduced to a short, entirely hollow body formed by coalescent tubes. On the other hand, when A. wiedenmayeri exhibits solitary tubes, they are quite regular and usually maintain the diameter and the tube wall thickness throughout their length.

At Rosario Islands, Bahamas and Jamaica, the authors collected specimens of a “club-shaped” form already mentioned and named by Carter (1883) Ectyon sparsus var clavaeformis This variety was synonymised with A. dispar by Alcolado (1976) and by Wiedenmayer (1977), but kept as a distinct form of this species by Alcolado (1976, 2002) and Alcolado & Busutil (2012). Apart from the club form, we found no other evidence of consistent specific differences with the more usual forms. We suspect that the “club-shape” and the Belizean tapered fingers forms are responses to environments with strong algal growth or abundant coral rubble or sediments, as a strategy to expose their oscules to the mainstream currents. Agelas sp2, as described by Pulitzer-Finali (1986), belongs to A. dispar as the spicule variation used by the author to separate the specimen is considered insufficient, taking into account the variation showed by the species.

Previously, some authors considered the existence of a red or orange form (van Soest 1981; Zea 1987), which besides the color, is somewhat similar externally to ball-shaped individuals of Agelas dispar . However, a less tight skeleton, irregularities in the spicule spination, and DNA evidence ( Parra-Velandia 2011) have shown that this form is conspecific with Agelas sventres Lehnert & van Soest, 1996, described below.

Several reports of red A. dispar thus need to be re-assessed. For example, that of Wintermann-Kilian & Kilian (1984) from Santa Marta ( Colombia), probably is a misidentification of A. sventres or most likely a small A. clathrodes , because we are quite sure that A. dispar does not occur at this locality. Assmann (2000) already made the distinction for these two morphotypes; of specimens pictured in his plate 6 (p. 90–91), only B and C belong to A. dispar ; specimens A and D are A. sventres . We examined his specimens ZMA POR 13372, 13374, 13376, and confirmed that they are A. dispar .

| ZMA |

Universiteit van Amsterdam, Zoologisch Museum |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Agelas dispar Duchassaing & Michelotti, 1864

| Parra-Velandia, Fernando J., Zea, Sven & Van Soest, Rob W. M. 2014 |

Agelas dispar

| Alcolado 2012: 69 |

| Alcolado 2002: 61 |

Agelas

| Pulitzer-Finali 1986: 113 |

Agelas sparsus

| Alcolado 1976: 4 |

Agelas dispar

| Alcolado 2012: 69 |

| Moraes 2011: 166 |

| Muricy 2011: 38 |

| Muricy 2008: 82 |

| Erpenbeck 2007: 1564 |

| Mothes 2007: 85 |

| Collin 2005: 650 |

| Alcolado 2002: 61 |

| Valderrama 2001: 49 |

| Assmann 2000: 38 |

| Soest 1998: 81 |

| Gammill 1997: 43 |

| Lehnert 1993: 50 |

| Pulitzer-Finali 1986: 107 |

| Sole-Cava 1981: 131 |

| Boury-Esnault 1973: 285 |

Agelas sparsus

| Alcolado 1976: 4 |

| Laubenfels 1936: 73 |

Agelas dispar

| Duchassaing 1864: 76 |