Baeus Halliday

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.177085 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5690864 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F5879F-526A-D134-FF68-4F92F179FACA |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Baeus Halliday |

| status |

|

Genus Baeus Halliday View in CoL

Baeus Halliday, 1833: 270 View in CoL . — Ashmead, 1893: 167; Kieffer, 1926: 146; Galloway & Austin, 1984: 86; Austin, 1988: 88; see Johnson, 2004, for complete bibliography [Type species, by monotypy, Baeus seminulum Haliday, 1833 View in CoL ].

Anabaeus Ogloblin, 1957: 440 —[Type species, by designation, Baeus (Anabaeus) ventricosus Ogloblin, 1957 View in CoL ]. Proposed as a subgenus of Baeus Haliday. View in CoL

Angolobaeus Kozlov, 1970: 218 . — Masner, 1976: 67; Johnson, 1992: 336 [Type species, by designation, Parabaeus machadoi Risbec, 1957 ]. Syn nov.

Hyperbaeus Foerster, 1856: 144 . — Masner, 1976: 67; Johnson, 1992: 457 [Type species, Baeus seminulum Haliday View in CoL ] Unnecessary replacement name for Baeus Haliday. View in CoL

Paraneurobaeus Risbec, 1956: 821 — Masner, 1976: 67; Johnson, 1992: 457 [Type species, by designation, Paraneurobaeus arachnevora Risbec, 1956 ]. Syn nov.

Psilobaeus Kieffer, 1926: 151 — [Type species, by monotypy, Baeus curvatus Kieffer, 1910 View in CoL ] Synonymy by Masner (1965).

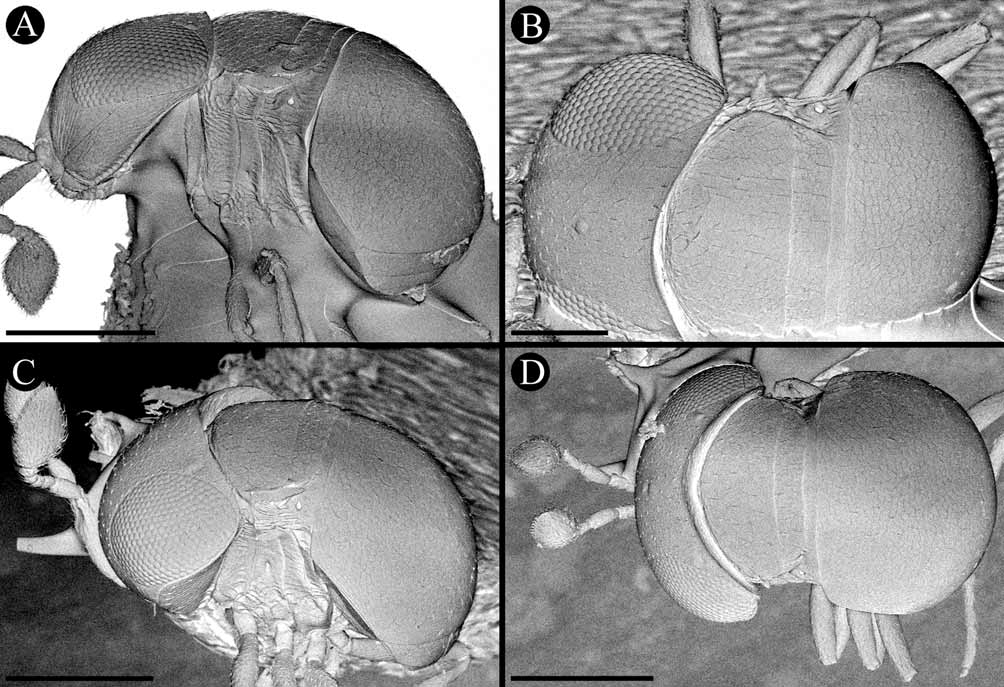

Diagnosis. Female. Head much wider than mesosoma, closely abutted to pronotum, marginally wider than

metasoma ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 D); lateral ocellus much closer to posterior margin of eye than to median ocellus ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 B);

hyperoccipital carina distinct along dorsal-posterior margin of vertex; occiput vertical and concave, not nor-

mally visible dorsally unless head flexed forward, always forming acute angle with vertex; posterior margin

of vertex concave medially; in dorsal and lateral views, frons rounded; in anterior view, head ovoid in shape;

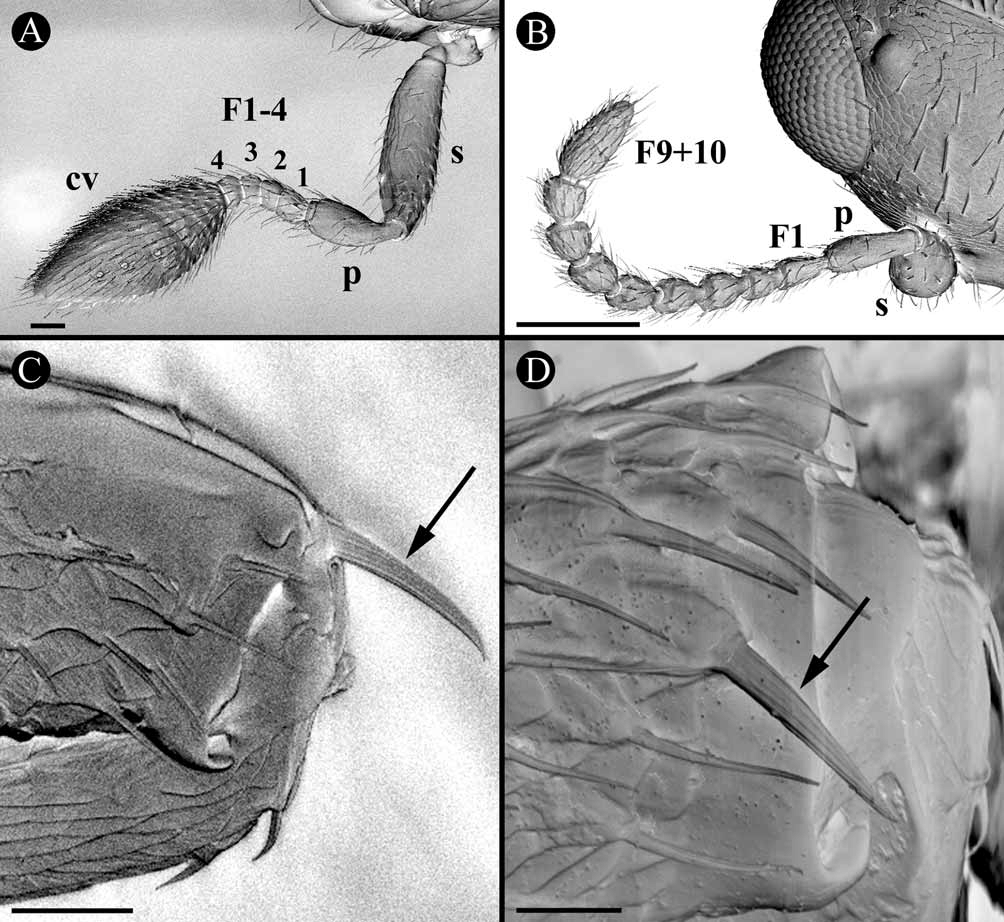

antenna 7-segmented ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 A), with 4 funicle segments, F1 about twice as long as each of F2–4 which are

transverse, clava unsegmented (fine suture lines present on dorsal surface only), densely pilose ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 A),

scape not reaching to median ocellus; frontal carina incomplete, not reaching to median ocellus ( Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 D);

antennal insertion positioned below ventral margin of eyes, between ventral margin of frons and dorsal margin

of clypeus; clypeus with transverse furrow just dorsal to its ventral margin, furrow with 6 bristles along dorsal

margin; mandibles tridentate; maxillary and labial palps 1-segmented, labial palps wart-like, bearing one bris-

tle, maxillary palps clavate, having three bristles apically; dorsally frons coriarious; malar region with cristu-

lations seemingly emanating from anterior tentorial pits ( Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 D); gena broad and distinct ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 A and 9E).

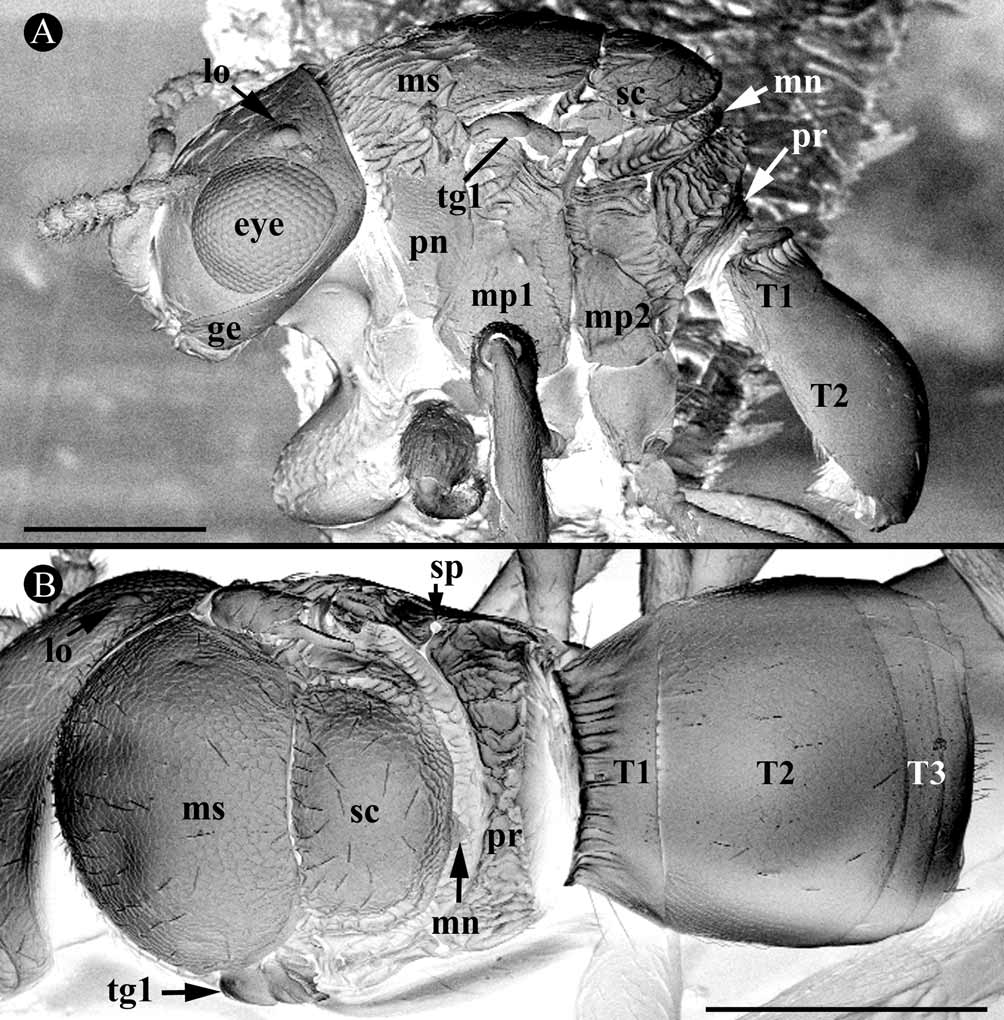

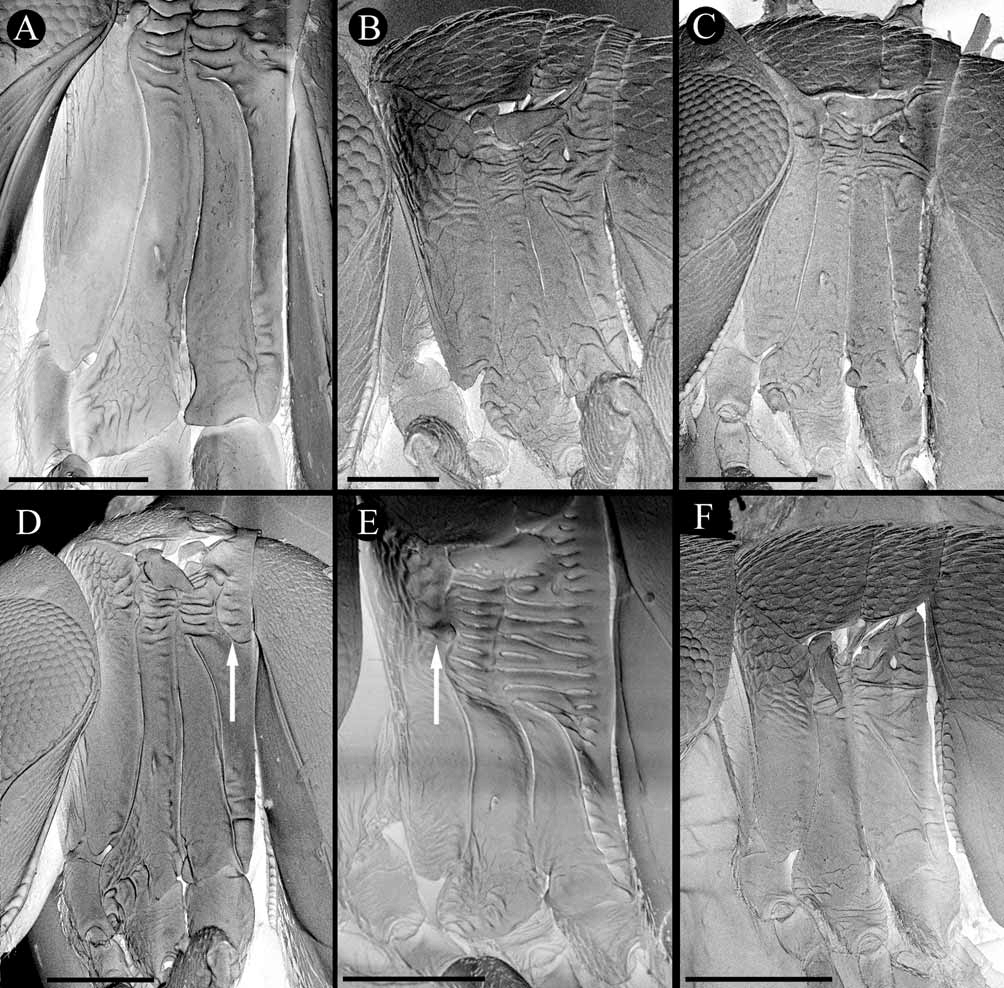

Mesosoma. Compact, higher and wider than long ( Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 A and 11D); both fore- and hindwings reduced to minute sclerotized plates that are often overlooked because they neatly fit into recesses beneath lateral margins of mesoscutum and mesoscutellum respectively, only marginally larger than tegula ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 A and 7B–F); pronotum visible latero-dorsally, but not medio-dorsally, dorso-posterior corner of pronotum bearing protuberance ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 E); mesoscutum much wider than long; mesoscutellum transverse, approximately one-third length of mesoscutum ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 B); metanotum greatly reduced, hidden beneath mesoscutellum so not visible (cf. Figs 4 View FIGURE 4 A and B to Figs 5 View FIGURE 5 A and B); posterior surface of propodeum vertical, dorsal surface forming thin transverse band, posterior margin extending over anterior margin of T2 ( Figs 4 View FIGURE 4 A and B); dorsal metapleuron fused with propodeum to varying degrees ( Figs 7 View FIGURE 7 A–F); coxae large, anterior surface densely covered with stout bristles; legs longer than mesosoma and metasoma combined, hind leg longest; hind leg femoral spine present or absent (sometimes difficult to see even at high magnification) ( Figs 6 View FIGURE 6 C and D).

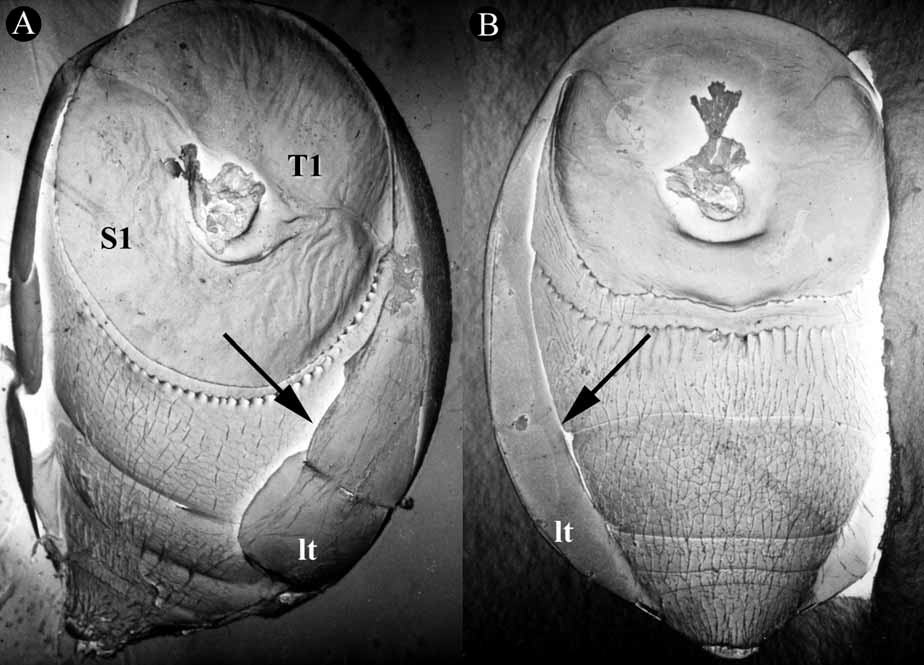

Metasoma. Short, broadly abutted against vertical posterior surface of propodeum so body appears fused ( Figs 4 View FIGURE 4 A and B); T1 and S1 forming vertical anterior surface of metasoma, T1 not visible dorsally ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 A); T2 largest tergite, occupying>0.6 of dorsal surface of metasoma ( Figs 4 View FIGURE 4 A and B), glabrous band present along posterior margin; laterotergites wide, ventral margins free, not incised into a submarginal groove (cf. Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 A to 3B).

Male. Body not rounded and fused, division between mesosoma and metasoma obvious ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ); dorsal surface of mesosoma well above that of metasoma; metasoma petiolate; sculpturing of all dorsal sclerites similar to female, usually more pronounced, except for propodeum and anterior margin of T1 which are visible and generally confused-rugulose and crenulate-costate, respectively; pilosity generally longer than female conspecifics but not as dense; colour similar to female conspecifics.

Head. Wider than mesosoma, but not as wide in relation to mesosoma as in female, closely abutted to pronotum; hyperoccipital carina distinct along dorsal-posterior margin of vertex; occiput vertical and concave, often forming acute angle with vertex (as in female); eyes not as large as in female, but more distinctly bulging from face; occelli more prominent; antenna 11 or 12-segmented, F9 and F10 sometimes fused or separated ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 B).

Mesosoma. More quadrate than transverse, length greater than width and height, though only marginally ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 A and B); mesoscutum wider than long; mesoscutellum often semi-ovoid in dorsal view, approximately half length of scutum, projecting posteriorly above metanotum; metanotum transverse, visible posterio-dorsally; propodeum with exposed oblique sculptured surface in anterior dorsal part, posteriorly surface more vertical and abutted against T1; sculpturing of dorso-lateral regions of meso- and metapleuron confused; wings present and macropterous ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 ); forewing narrow so that anterior and posterior margins almost parallel; submarginal (Sc+R) + marginal (R1) veins only reaching about 0.4 times along wing length, marginal vein short, stigmal vein (r) much longer than marginal vein, basal vein (Rs+M) present as thickened infuscate band; setal fringe present and long except for proximal posterior margin; hindwing extremely narrow, setal fringe on posterior margin much longer than maximum wing width.

Metasoma. Petiolate, short, usually shorter than mesosoma; T1 clearly visible dorsally; T2 the largest tergite but not as dominant as in female; ventral surface often collapsed inwards so concave; laterotergites free and wide as in female, but difficult to see when metasoma has collapsed ventrally.

Monophyly and relationships of Baeus

The monophyly of Baeus is supported by eight critical characters associated with the female sex: 1) the female metasoma is short, convex, wide anteriorly and broadly abutted against the vertical surface of the mesosoma so the body appears to be rounded and fused ( Figs 4 View FIGURE 4 A & B), 2) T1 and S1 are wafer thin and form the semi-vertical anterior surface of the metasoma ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 A); because of this arrangement, T1 is not visible dorsally ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 B), 3) T2 is the largest tergite, comprising at least 0.6 times the length of the metasoma ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 A & B), 4) the laterotergites of the metasoma wide and free, not incised into a submarginal groove as in Mirobaeoides ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 A cf. 3B), 5) the propodeum is vertical and forms the whole of the posterior surface of the mesosoma, 6) the metanotum is reduced and hidden below the mesoscutellum, 7) the maxillary and mandibular palps are reduced to a single segment, and 8) the wings are micropterous, i.e. both fore- and hindwings reduced to minute sclerotized plates, the forewing only slightly larger than the tegula, therefore, often referred to as ‘wingless’ ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 A, 7B–F). In addition, the male is characterized by having the forewing narrow so that the anterior and posterior margins are almost parallel, the submarginal + marginal veins only about 0.4 times the length of the wing, and a basal vein is usually present ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 ).

Of the female characters above, a rounded, apparently fused body (character 1) is found in the genera Mirobaeoides , Neobaeus and two undescribed baeine genera from southern Africa (in CNC); the laterotergites being wide and free (character 4) is found independently in Neobaeus , Tiphodytes Bradley (Thoronini) and all members of the Telenominae ( Masner 1976) , while the forewings being reduced to a tiny sclerotized flaps (character 8) is found in numerous taxa across the Scelionidae and Platygastridae , particularly those associated with soil and litter habitats ( Austin et al. 2005). The other characters listed above are all apparently unique to Baeus .

The phylogeny of the Baeini was first examined by Iqbal and Austin (2000a) using a morphological dataset for exemplar species representing virtually all described genera as well as five putatively undescribed generic level taxa. Parsimony analysis resolved Baeus as monophyletic but only with the inclusion of Apobaeus Ogloblin , a potential synonym of Baeus from the Neotropics. To date we have been unable to examine the type species of Apobaeus ( Tetrabaeus insularis Ogloblin ), and the generic status of this taxon remains unclear. In this analysis, virtually all ‘wingless’ taxa formed a monophyletic group, with Baeus + Apobaeus being placed apically and sister to Neobaeus and then Mirobaeoides . However, removal of wing size character states from the dataset resulted in a largely comb-like tree, and pointed to the fact that in the absence this character, which is notoriously homoplastic, there were few informative characters to infer relationships among genera. However, as partly outlined in the Introduction, a recent molecular study (Carey et al. 2006), including 23 baeine species representing seven genera and eight non-baeine scelionids, resolved Baeus as monophyletic but placed it in a more basal position as sister to Odontacolus + Hickmanella + Idris + Ceratobaeus , with the latter two genera being polyphyletic. Further, in this analysis the Baeini was not monophyletic as Mirobaeiodes + Neobaeus were resolved with other scelionid genera. These results have been confirmed within a broader sampling of taxa, and point to the fact that the Baeini is not monophyletic and that scelionids have probably exploited spider eggs independently at least twice (Murphy et al. in press).

Comments on non-Australian genera

Prior to the commencement of the current study, one of us ( ADA) was able to examine the types of two monotypic baeine genera, Angolobaeus Kozlov and Paraneurobaeus Risbec. Both of these genera are here proposed as junior synonyms of Baeus .

Kozlov (1970) erected Angolobaeus for Parabaeus machadoi Risbec from Angola ( Risbec 1957) (holotype in MRAC) on the basis that the type species has the vertex and frons with two “mound-like projects” on each. Parabaeus Kieffer is morphologically highly convergent with Baeus -like scelionids, but the genus belongs to the Platygastridae as recognized by Masner (1976) (see also Austin 1988; Manser & Huggert 1989). Kozlov (1970) correctly placed P. machadoi as a scelionid and a member of the Baeini . However, there is no justification for the generic status of this species; it is congeneric with Baeus in every respect except for the cephalic projections, which we propose are simply autapomorphic and of importance only at the species level. A range of cephalic processes also occur on the head of some Telenomus (Telenominae) ( Mineo 1979; Johnson 1980; Huggert 1983) and the vertex and eyes of some Platygastridae (Austin 1984) , where they are also only of species level importance.

Risbec (1956) described Paraneurobaeus for a species reared from spider eggs collected at Garoua ( Cameroon) that appeared to have a 6-segmented, rather than a 7-segmented, antenna. The type species, Paraneurobaeus arachnevora Risbec , is represented by a syntypic series (MNHN) mounted on two microscope slides. Unfortunately, Risbec’s description is inaccurate and his drawings look nothing like the slide mounted specimens that are in reasonable condition. Examination of the type series shows in fact that the antenna is 7- segmented and that three (not two) tiny funicle segments are present in addition to the larger basal funicle segment, as is the case in Baeus and most other members of the tribe. In every respect, this species is congeneric with Baeus . The specimen on one slide with the head attached we here designate as the lectotype of P. arachnevora , and the remaining specimens that are slightly broken as paralectotypes.

Biology

Although there are numerous series of Baeus reared from spider eggs in world collections, in most cases the host spider has not been identified. Austin (1985) summarised all available host information for parasitoids associated with spider eggs and, worldwide, 22 species of Baeus have host data recorded to at least family level. Although the data are limited, it does point to this genus parasitising a narrower spectrum of spider host families compared with the largest genus of baeines, Idris . Where Baeus has been reared from six spider families, more than 70% of which come from just two families ( Araneidae – 9 records and Theridiidae – 7 records), Idris has been reared from 11 host families (22 records). Interestingly, the spider hosts for Baeus have uniformily more complex structured eggsacs compared with the hosts of Idris , in that they have either dense flocculent silk walls or have multiple layers of dense and flocculent silk (types 2 and 3, viz. the eggsac classification proposed by Austin 1985). Further, it has been postulated that the highly modified body shape of Baeus may also function as an adaptation for the female wasp to burrow through the silk wall of the eggsac to reach and oviposit into the eggs within ( Austin 1988; Austin et al. 2005). However, some caution should be exercised in not over-interpreting the above apparent difference as there is likely to be some bias in the host data for Baeus in that most records come from spider hosts collected from above-ground vegetation (where eggsacs are easy to locate and collect), rather than from soil and leaf-litter where Baeus appear to be more abundant.

For Australia, Baeus have been reared from three spider families (Table 2); Araneidae , Lynyphidae and Theridiidae with four of the six records being from the araneid genera Araneus , Argiope , Celaenia and Cyrtophora , all of which produce eggsacs attached to vegetation. Individual host data are given below for two Baeus species, however for the other four host records the material was not available to examine and the species had not been identified.

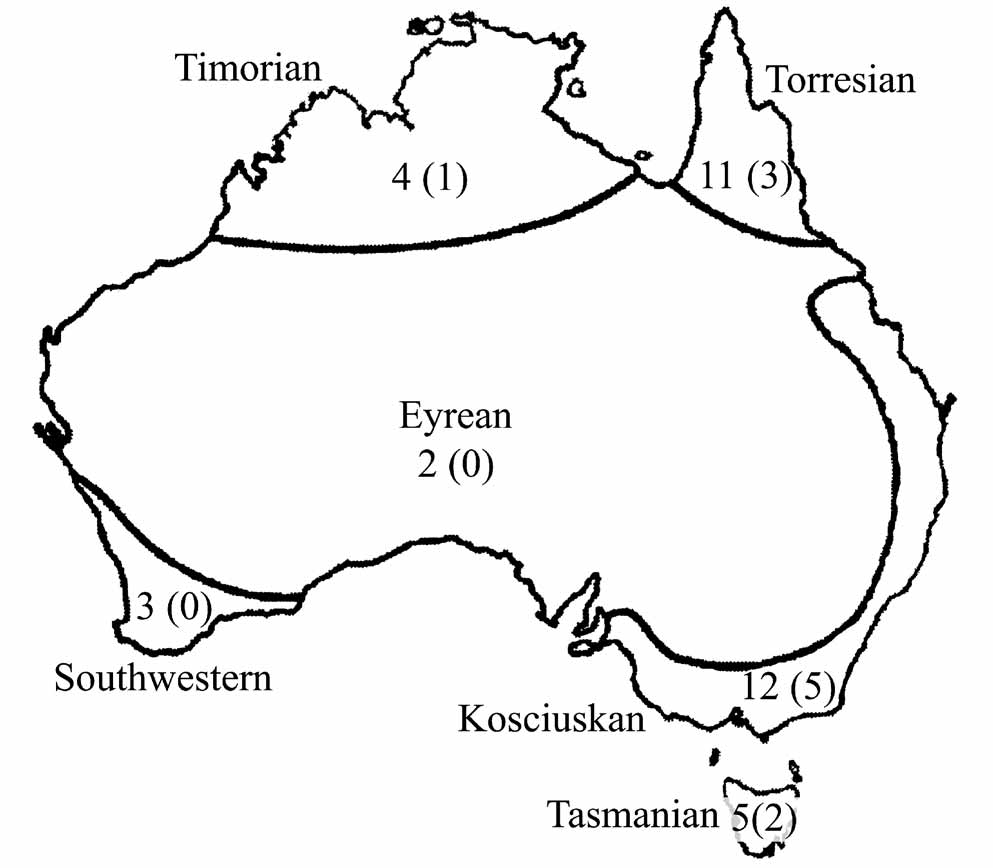

Distribution. The greatest diversity of Australian Baeus species exists within the peripheral mesic environments of the continent, a common pattern exhibited by their hosts ( Raven 1988). Of the 20 species treated here, 55% are endemic to a single biogeographic subregion, with the highest level of endemism found in the Kosciuskan subregion (25%) ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ). The eastern seaboard of the continent, from northern Queensland to southern New South Wales, exhibit the greatest species richness ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ) and share the most number of species ( Table 3 View TABLE 3 ). The lowest number of species occurs in the South-Western and Eyrean subregions which have no endemic taxa, although these areas are also the poorest surveyed. In addition, we have recognized a further eight likely new species, but have refrained from describing them because of the limited material available and/or their poor condition. Five of these species are from the Kosciuskan subregion, two of which also occur in other subregions, one in the South-West, the other extending into the Torresian subregion. The Tasmanian, Timorian, and Torresian subregions each have a single undescribed species. It is likely that numerous additional species will be discovered in the future as more long-term collecting using a range of techniques is undertaken in specific habitats.

Although beyond the scope of the current study, available material of Baeus from New Zealand and islands surrounding Australia were also examined. Apparent from this is a close affinity of the neighbouring Pacific fauna with the Australian fauna. For instance, New Zealand has a relatively small fauna comprising five species, two of which also occur in Australia ( B. leai and B. saliens ). Of the remaining three species, two are similar to B. murphyi and B. saliens , and may be indicative of allopatric speciation events. The Baeus species found to occur on several neighbouring Pacific islands from which material was available ( Norfolk Island, Lord Howe Island, New Caledonia, and Fiji) all belong to species also present in Australia. This close affinity is in stark contrast to the Baeus fauna of Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean, some 2000 km to the north-west of Australia. Of the five species found to occur on Christmas Island, only one, B. tropaeumusbrevis is also present in Australia. Interestingly, B. tropaeumusbrevis in Australia has only been collected from the north-west of Australia, the closest region of the Australian mainland to Christmas Island. This difference between the Christmas Island and Australian fauna’s is hardly surprising given that the islands of the Sunda Arc to the north, particularly Java and Sumatera, are the closest landmasses to Christmas Island, and the direction of the prevailing winds may facilitate colonisation from Indonesia. Study of the Baeus fauna of the neighbouring Indonesian islands may reveal a close affinity with the Christmas Island fauna, as Smithers (1995) has documented for the Psocoptera. The distribution of B. tropaeumusbrevis appears to be an example of colonisation of Australia from the north-west.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Baeus Halliday

| Stevens, Nicholas B. & Austin, Andrew D. 2007 |

Angolobaeus

| Masner 1976: 67 |

| Kozlov 1970: 218 |

Anabaeus

| Ogloblin 1957: 440 |

Paraneurobaeus

| Masner 1976: 67 |

| Risbec 1956: 821 |

Psilobaeus

| Kieffer 1926: 151 |

Baeus

| Austin 1988: 88 |

| Galloway 1984: 86 |

| Kieffer 1926: 146 |

| Ashmead 1893: 167 |

Hyperbaeus

| Masner 1976: 67 |

| Foerster 1856: 144 |