Leopardus pardalis (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1206/00030090-417.1.1 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5489378 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03E587EC-FF99-FF82-76D6-FA3983AAFA51 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Leopardus pardalis (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| status |

|

Leopardus pardalis (Linnaeus, 1758) View in CoL

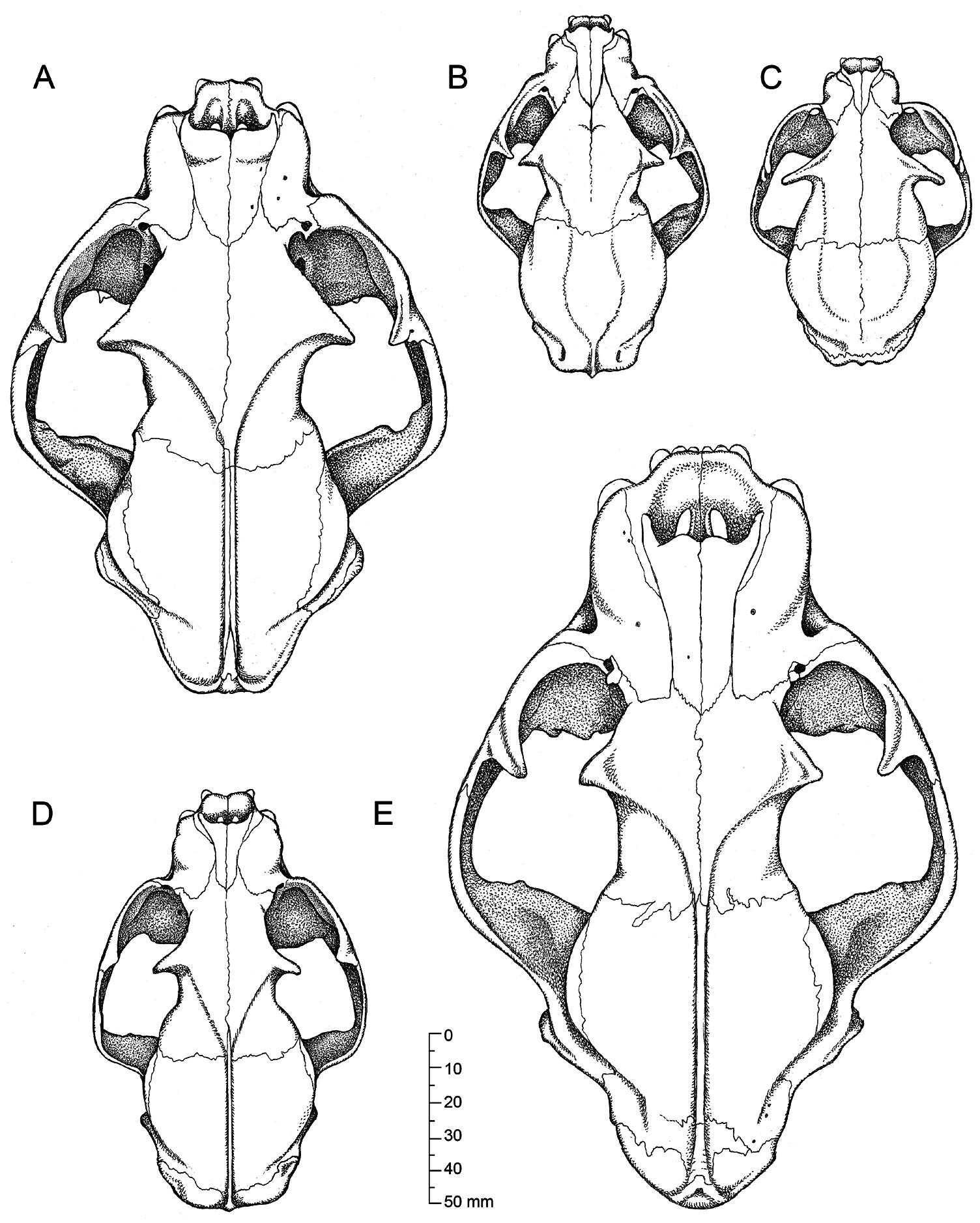

Figure 14D View FIG

VOUCHER MATERIAL (TOTAL = 5): Boca Río Yaquerana (FMNH 88887), Nuevo San Juan (MUSM 11170, 13150), Orosa (AMNH 73762), Quebrada Esperanza (FMNH 88888).

OTHER INTERFLUVIAL RECORDS: Jenaro Herrera (Pavlinov, 1994), Quebrada Pobreza ( Escobedo-Torres, 2015), Río Yavarí (Salovaara et al., 2003), Río Yavarí-Mirím (Salovaara et al., 2003), San Pedro (Valqui, 1999).

IDENTIFICATION: The ocelot ( Leopardus pardalis ) and the margay ( L. wiedii ) are gaudily streaked-and-spotted small cats with reversed nuchal fur (the hairs of the nape pointing forward rather than backward; Pocock, 1941). 7 Ocelot specimens from northeastern Peru are consistently larger than margays in most measured dimensions ( table 12 View TABLE 12 ), and these species can also be distinguished by external and cranial proportions (see the account for L. wiedii , below).

Numerous subspecies of the ocelot are currently recognized as valid (e.g., by Wozencraft, 2005), but it is not known whether any represent taxonomically meaningful subdivisions. The last specimen-

7 The oncilla ( Leopardus tigrinus ), if it really does occur in our region (see above), has unreversed nuchal fur (Nascimento and Feijó, 2017).

based revision was Pocock’s (1941), who assigned all the Peruvian material he examined to the subspecies L. p. aequatorialis (Mearns, 1902), the type locality of which is in the Pacific lowlands of northern Ecuador. Although Eizirik et al. (1998) suggested that several phylogeographic partitions are present within L. pardalis , their study did not include any western Amazonian sequence data, so the assignment of our material to any of the phylogroups they recognized is problematic. In the absence of any compelling reason for trinomial nomenclature, it seems pointless to speculate about the subspecific assignment of our material.

ETHNOBIOLOGY: The Matses name for the ocelot is bëdimpi, the term for jaguar/feline with the diminutive suffix mpi. It has no other names and no varieties are distinguished by the Matses. The term bëdimpi can also be a more general term that includes the ocelot , the margay, the jaguarundi, and the house cat.

The ocelot is of no economic importance to the Matses. It is not eaten or kept as a pet. The Matses are not afraid of ocelots, because they are too small to attack humans. However, ocelots enter villages to eat chickens in their coops at night, and they prowl around near villages in the daytime to attack free-ranging chickens on the outskirts of clearings. Once an ocelot kills and eats a chicken, it keeps coming back to get more. When an ocelot becomes a pest in this way, the Matses hunt it down with dogs.

Matses with young children avoid having any contact with or even looking at ocelots, lest the ocelot’s spirit make their children ill (see the ethnobiology entry for Puma concolor for details on symptoms and treatment of contagion by felids).

MATSES NATURAL HISTORY: The ocelot is small and spotted.

The ocelot is found in any type of habitat, including upland and floodplain forest, and primary and secondary forest. It mainly walks on the ground, but also often climbs trees.

The ocelot is diurnal and nocturnal. It walks following streams, sniffing as it hunts. Or it lies in wait for prey on the ground or sitting up in a tree. It lies on fallen trees in blowdowns to warm itself in the sun. It sleeps on trees that lean somewhat horizontally. It defecates in habitats called “demon’s swiddens” that have an open understory. 8

The ocelot is solitary. Sometimes two are seen together, perhaps male and female. The ocelot gives birth to two kittens in a hollow log or in a hole in the ground.

During the day ocelots kill agoutis and acouchies, and at night they kill pacas. As an ocelot walks along a small stream at night it may find and catch a paca that is eating aquatic snails. Then it drags the paca to dry land to eat it. It may dig into an acouchy burrow when it chases one into its burrow. The ocelot stalks its prey crouching, as it slowly advances, and then pounces on

the quarry, grabs it with its claws, and bites its head. Ocelots go to drink water repeatedly while eating. An ocelot will stash part of the kill, if it is a large animal.

The ocelot growls when it is taking prey.

Ocelots eat pacas, agoutis, acouchies, spiny rats, opossums, tinamous, other terrestrial birds, lizards, and jungle frogs (Leptodactylu s spp. [ Leptodactylidae ]).

REMARKS: Matses observations about ocelots largely overlap with the scientific literature on this common and widespread species, notably agreeing with the results of radio-tracking studies in rainforest habitats ( Emmons, 1988; Aliaga- Rossel et al., 2006) with respect to diel activity pattern, killing behavior, and caching of large prey. Curiously, Matses observations suggest that twinning is common for ocelots, whereas most captive litters consist of a single young ( Havlanová and Gardiánová, 2013).

The Matses list of ocelot prey closely resembles that obtained by analyzing scat at another Peruvian rainforest site ( Emmons, 1987), but not with known ocelot diets from other rainforested regions. In particular, the Matses list omits sloths, which are said to be commonly eaten by Central American ocelots (e.g., by Moreno et al., 2006), and primates, which are often eaten by ocelots in southeastern Brazil ( Bianchi and Mendes, 2007). To the best of our knowledge, no previous dietary study has reported that ocelots eat frogs. The omission of any mention of ocelot frugivory by our informants seems noteworthy by contrast with lists of fruits eaten by jaguars, pumas, and jaguarundis in Matses accounts of those species (see below).

TABLE 12 Measurements (mm) and Weights (g) of Adult Specimens of Leopardus pardalis and L. wiedii from the Yavarí-Ucayali Interfluve

| L. pardalis | L. wiedii | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMNH 73762 | FMNH 88888 | MUSM 11170 | FMNH 88887 | MUSM 13150 | FMNH 88889 | |

| Sex | female | female | female | male | male | male |

| Head-and-body length | — | 730 | 608 | 755 | 687 | 543 |

| Length of tail | — | 323 | 362 | 330 | 331 | 355 |

| Hind foot | — | 155 | 163 | 166 | 150 | 134 |

| Ear | — | 55 | 51 | 57 | 62 | 47 |

| Weight | — | — | 9200 | — | 9150 | — |

| Condylobasal length | 124.1 | 123.3 | 122.7 | 127.6 | 125.2 | 91.8 |

| Nasal length | 35.4 | 34.5 | 32.9 | 32.3 | 33.5 | 22.8 |

| Least interorbital breadth | 26.8 | 23.2 | 23.9 | 25.0 | 22.8 | 16.8 |

| Least postorbital breadth | 35.4 | 27.9 | 32.7 | 26.8 | 27.5 | 34.3 |

| Zygomatic breadth | 88.1 | 85.0 | 88.0 | 88.6 | 87.0 | 64.7 |

| Maxillary toothrowa | 41.3 | 41.7 | 41.6 | 41.0 | 42.9 | 28.9 |

| Length P4 | 15.1 | 16.6 | 16.2 | 15.6 | 17.0 | 11.6 |

| Width P4 | 7.4 | 8.6 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 6.3 |

Measurements (mm) and Weights (g) of Adult Specimens of Leopardus pardalis

and L. wiedii from the Yavarí-Ucayali Interfluve

a From C1 to M1.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.