Dinonemertes shinkaii, Kajihara, Hiroshi & Lindsay, Dhugal J., 2010

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.293307 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6200020 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03DDEE4E-FF83-5D02-FF7A-FD9FC8567019 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Dinonemertes shinkaii |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Dinonemertes shinkaii sp. nov.

( Figs 1–5 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 )

Material examined. Holotype, JAMSTEC 6K549SS4, female, serial transverse sections, 112 slides.

Diagnosis. Body translucent, broad and flat; tail fin indistinct; tentacles absent; mouth and rhynchodaeum separate; lateral body wall muscles rudimentary; lateral nerve cords close to the body wall, without lateral nerve cord muscles; mid-dorsal blood vessel reaching posterior end of body, entering rhynchocoel; cephalic blood vessel present; rhynchocoel half the body length, with wall comprised of outer circular, middle longitudinal, and inner circular muscle layers; proboscis with 24 nerves; caecal diverticula 2 pairs; about 25 pairs of intestinal diverticula, widely separated by parenchyma, slightly lobed; ventral branch of intestinal diverticula absent; dorsal intestinal diverticula do not meet above rhynchocoel; intestinal diverticula extend laterally beyond nerve cords; anterior intestinal caecal diverticula do not reach brain; arrangement of testes unknown; sex separate; band-shape organs absent.

Description. External features. The body is broad and flattened ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 A). In life, the body is translucent and the internal organs are visible; the brain is pale orange; the stomach, proboscis, lateral nerve cords, and ovaries are white; and the intestine is reddish ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 B). On board the R. V. Yokosuka the anterior end of the body around the mouth is somewhat protuberated ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 C), while it is not in the natural shape ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 A); this might be caused by the distortion of the anterior alimentary canal as a result of the pressure change. The tail is broad, without a distinct fin. After fixation, the intestine became pale orange; the preserved specimen measured 3.3 cm in length, 1.0 cm in maximum width, and 6.0 mm in thickness ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 D).

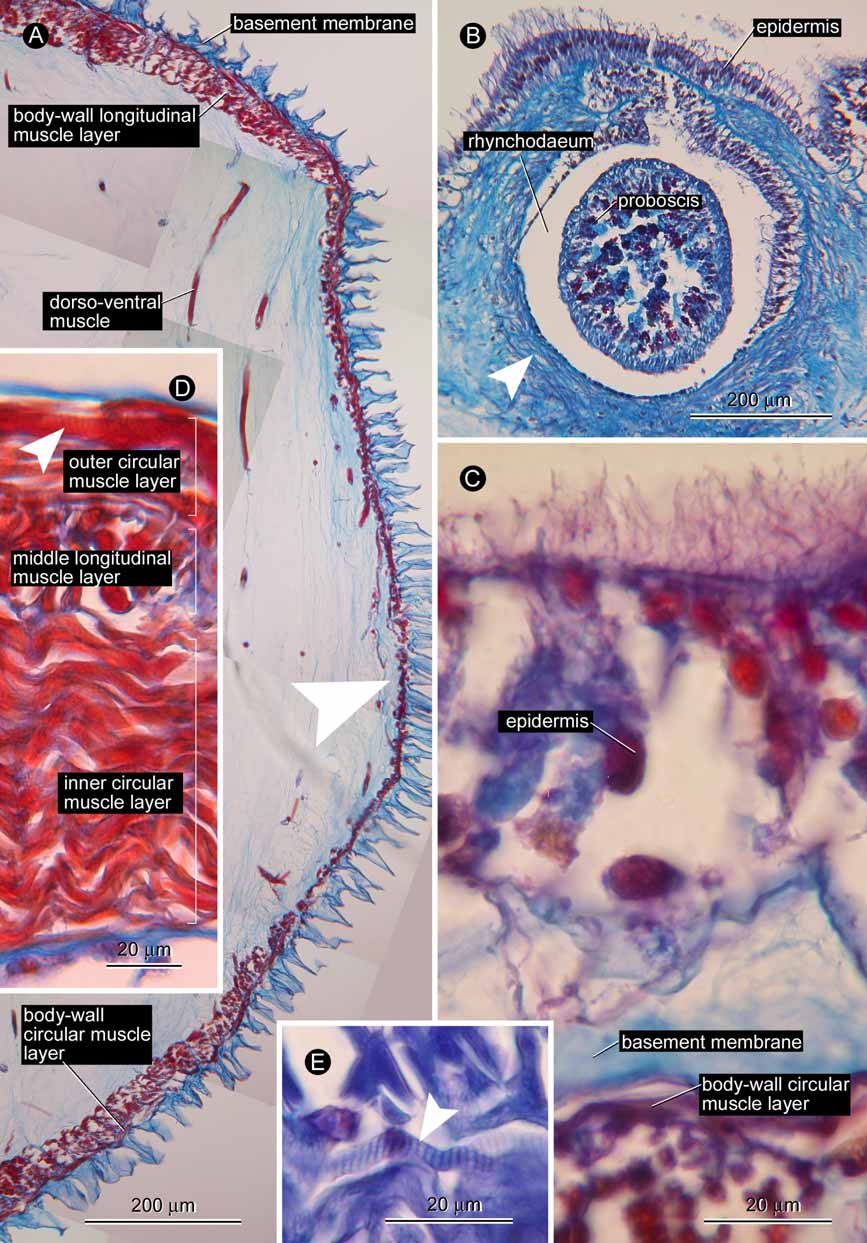

Body wall, musculature, and parenchyma. The epidermis was almost completely lost before fixation ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 A) except for small areas on the extreme anterior tip of the head ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 B), and on the dorsal surface in the posterior region of the body ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 C). The connective tissue basement membrane has a deep cup-like structure ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 C). The body-wall musculature consists of outer circular and inner longitudinal muscle layers, up to 10 and 30 µm thick, respectively; these are rudimentarily developed on the lateral sides of the body ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 A). The presence/absence of the diagonal muscle layer was not ascertained in cross sections. Dorsoventral muscles are not strongly developed ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 A), each containing up to five, smooth muscle fibres; dorsoventral muscles are found throughout the body, running in the parenchyma beside the rhynchocoel, alimentary canal, lateral nerves, and gonads. The parenchyma is extensively developed throughout the body ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 A).

Proboscis apparatus. The rhynchodaeal opening, separated from the mouth, is situated at the tip of the head. The rhynchodaeum is encircled with circular muscle layer just in front of the proboscis insertion ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 B), which is situated immediately anterior to the brain.

The rhynchocoel extends to half the body length. In the brain region, the rhynchocoel wall is composed of an outer longitudinal and inner circular muscle layers, 100 µm and 25 µm in thickness, respectively; these layers are partially interlaced. Further backward, an outer circular muscle layer emerges so that the rhynchocoel wall consists of three (thin outer circular, middle longitudinal, and thick inner circular) muscle layers ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 D); in the foregut region, the outer circular muscle layer reaches up to 20 µm in thickness, the middle longitudinal layer 30 µm, and the inner circular layer 90 µm. At least fibres in the inner and outer circular muscle layers of the rhynchocoel are striated ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 D, E).

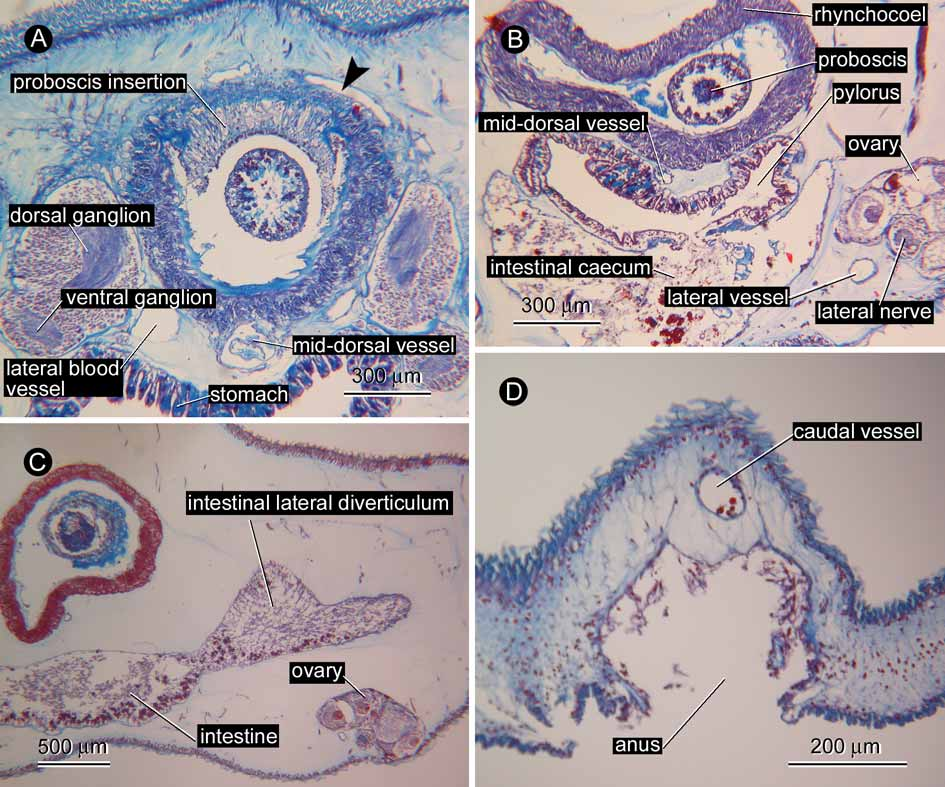

The proboscis was everted during fixation ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 D). The proboscis insertion is situated just in front of the brain; contributions to the proboscis insertion from the body-wall musculature were unable to be ascertained. The anterior chamber consists of a glandular epithelium folded into distinct conical papillae, a thick outer circular muscle layer embedded in well developed connective tissue, a longitudinal muscle layer containing proboscis nerves, a thin inner circular muscle layer, and a delicate endothelium The proboscis nerves, 24 in number, are peripherally connected by nerve fibres ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 A); the connections often contain nerve cells to form tiny ganglia, which occasionally innervate the outer circular muscle layer ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 B). In everted portion, the connective tissue layer containing the outer circular muscles attains 80 µm in thickness, the outer portion of the longitudinal muscle layer 50 µm, the peripheral nervous layer 30 µm, the inner portion of the longitudinal muscle layer 60 µm, and the inner circular muscle layer 20 µm. Detailed morphology of the middle chamber was difficult to reconstruct from the serial sections. The posterior chamber consists of a glandular epithelium containing acidophilic granules, a nervous layer, a longitudinal muscle layer, an outer circular muscle layer, and an endothelium ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 C). Anteriorly, the nerves in the posterior proboscis chamber are clumped into 24 nodes ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 C), but these become scattered posteriorly to form a rudimentary layer between the longitudinal muscle layer and the epithelium ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 D).

Alimentary system. The stomach was everted during fixation; as a consequence, the mouth, together with its periphery, was detached from the body ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 D); therefore, the morphology of the anterior portion of the alimentary system including the oesophagus is unknown. The stomach wall contains basophilic gland cells ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 A); posteriorly, the wall reduces in thickness and the number of basophilic cells decreases, as the stomach leads to the pylorus that opens to the dorsal wall of the intestinal caecum ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 B). Spranchnic muscles around foregut wall not found. The intestinal caecum, about 1 mm in length, possesses two pairs of lateral pouches (three pairs, if the ones that arise from the pylorus-intestine junction are counted); the intestinal caecum and its lateral pouches do not reach the brain. The intestinal lateral diverticula are simple, occasionally only slightly lobed, 25 pairs in number, more or less densely packed, and without ventral branches; the dorsal intestinal diverticula do not meet above the rhynchocoel, extending laterally beyond the lateral nerve cords ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 C). The anus opens ventrally at the posterior end of the body ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 D).

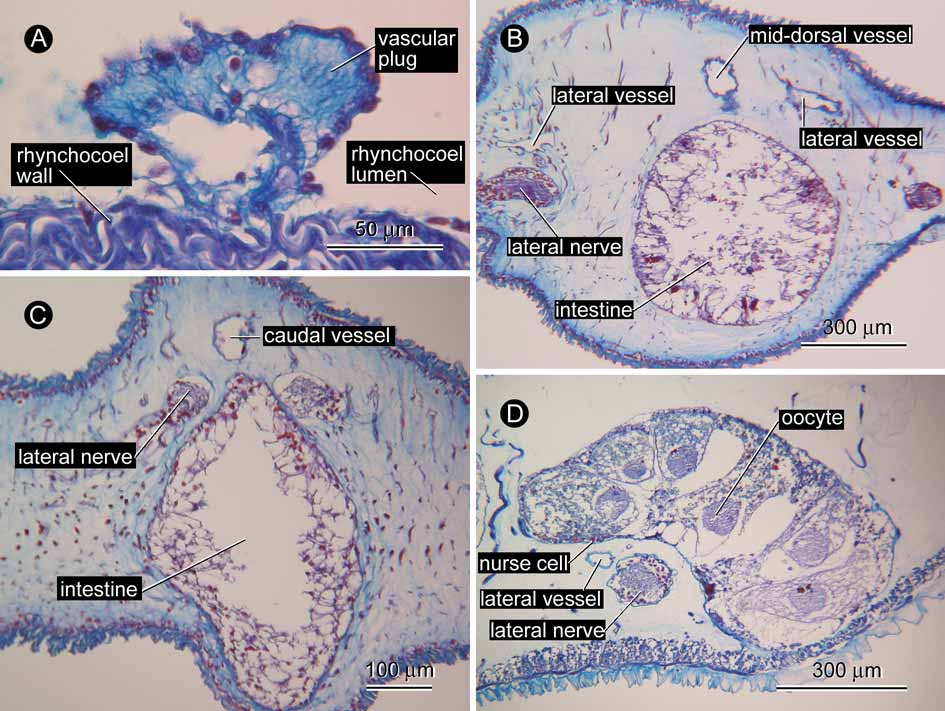

Blood system. A pair of cephalic vessels meet each other above the rhynchodaeum ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 A). The vessels lead backward to anastomose below the rhynchocoel just behind the ventral cerebral commissure, then trifurcate to lead to a pair of lateral vessels and a mid-dorsal vessel. Soon after its origin, the mid-dorsal vessel enters the ventral wall of the rhynchocoel for about 1.2 mm in the antero-posterial direction to form a distinct vascular plug ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 A). Near the caudal end ( Fig 5 View FIGURE 5 B), the lateral vessels merge with the mid-dorsal vessel anterior to the posterior nervous commissure; from the portion where the three vessels merge, a caudal vessel extends further posteriorly for about 90 µm ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 C) before terminating blindly above the anus ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 D).

Nervous system. The brain has outer neurilemma, but no inner neurilemma, without neurochord cells; the dorsal commissure is 70 µm in thickness, the ventral 130 µm. The lateral nerve chords are situated near the body wall, without accessory neuropils or lateral nerve cord muscles; myofibrils are not found. A mid-dorsal nerve extends backward in the body-wall basement membrane from the pyloric region; its anterior end could not be traced with certainty.

Excretory system. Absent.

Sensory system. No apical organ, cerebral organ, band-shaped organs, eyes, or cephalic glands were found.

Glandular system. Neither cephalic glands, nor postero-lateral glandular organs were found.

Reproductive system. The single specimen is female. About 20 ovaries are antero-posteriorly arranged in a row on each side, alternating with the intestinal lateral diverticula, distributed from the pyloric region to the posterior 2/3 of the body. Each ovary is tubular in structure, curved above the lateral nerve cord. No open gonopore was observed. In each ovary, up to 6 oocytes with about 300 µm in maximum diameter are linearly arrayed; these were in a similar vitellogenic condition, surrounded by nurse cells ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 D). Gonadal musculature not found.

Behaviour/Ecology. Upon first observation the specimen appeared neutrally buoyant with its head up, anterior two-thirds of body vertical, and distal third of body slightly curved. It remained in this neutrally buoyant, stationary position for at least 2 minutes and 33 seconds, not reacting to the lights of the submersible, until it was stimulated into swimming by water movement caused by the proximity of the Shinkai 6500. Swimming was accomplished by beating the posterior third of the body at a constant rate of approximately 1 Hz for one minute and 36 seconds until its collection. During swimming the specimen slowly rotated in an anticlockwise direction, therefore spiralling as it swam. No positive or negative phototaxis was observed. The only other plankton visible to the naked eye in close proximity was the chaetognath Eukrohnia fowleri —the similar orange pigmentation and co-occurrence suggesting the possibility it may be a prey item of this nemertean species.

Etymology. The specific epithet shinkaii is a noun in genitive case, taken after the name of the manned submersible Shinkai 6500 that collected the holotype of the species.

Remarks. The characteristics of the present specimen include a large, broad, and flat body; the mouth and the rhynchodaeum opening separately; rhynchocoel limited to 1/2 of the body, with a wall composed of inner circular, middle longitudinal, and outer circular muscle layers; and intestinal diverticula not distinctly branched. These features agree with the generic diagnosis given by Coe (1954: 245) for Dinonemertes Laidlaw, 1906 . Up to the present, four species of Dinonemertes have been described: D. alberti ( Joubin, 1906) , D. arctica Korotkevich, 1977 , D. grimaldii ( Joubin, 1906) , and D. investigatoris Laidlaw, 1906 . The present new species Dinonemertes shinkaii can be distinguished from its congeners in having 24 proboscis nerves, two pairs of lateral pouches in the intestinal caecum, and 25 pairs of intestinal lateral diverticula, whereas D. alberti possesses 28 proboscis nerves, two pairs of lateral pouches in the intestinal caecum, and 50 pairs of intestinal lateral diverticula ( Brinkmann 1917b; Korotkevich 1955, 1977); in D. arctica , the number of proboscis nerves is 28–30, with 5–6 pairs of intestinal caecal lateral pouches and 40 pairs of intestinal lateral pouches ( Korotkevich 1977); D. investigatoris has more than 30 proboscis nerves, three pairs of intestinal caecal pouches, and 60–70 pairs of intestinal lateral diverticula ( Brinkmann 1917b). The morphology of D. grimaldii is poorly known, but the body of this species is orange-red in life ( Joubin 1906), not transparent as in the other congeners, including D. shinkaii .

While the vast majority of nemerteans possess smooth muscle fibres, so far 17 species belonging to five families in Pelagica have been reported to possess pseudostriated muscle fibres. These are: in Armaueriidae , Neoarmaueria crassa ( Korotkevich, 1955) , N. tenuicauda ( Korotkevich, 1955) , and Xenarmaueria acoeca ( Korotkevich, 1955), reported by Korotkevich (1955), and Proarmaueria cf. pellucida (Coe, 1926) , reported by Norenburg and Roe (1998); in Nectonemertidae , Nectonemertes acanthocephala Korotkevich, 1955 , and N. major Korotkevich, 1955 , reported by Korotkevich (1955), and Nectonemertes cf. mirabilis (Verrill, 1892) , reported by Norenburg and Roe (1998); in Pelagonemertidae , Pelagonemertes brinkmanni Coe, 1926 , P. excisa Korotkevich, 1955 , P. laticauda Korotkevich, 1955 , P. oviporus Korotkevich, 1955 , reported by Korotkevich (1955), Obnemertes solida Korotkevich, 1964 and Pelagonemertes parvula Korotkevich, 1964 , reported by Korotkevich (1964); in Planktonemertidae , Crassonemertes cf. robusta (Brinkmann, 1917) , and Crassonemertes sp., reported by Norenburg and Roe (1998); and two undetermined species of Protopelagonemertidae reported by Norenburg and Roe (1998). Dinonemertes shinkaii is the first representative of the family Dinonemertidae to be confirmed to have pseudostriated muscle fibres.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Pelagica |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |