Hylobates lar (Linnaeus, 1771)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6727957 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6728291 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D787BA-0E3A-FFC5-FADA-F331F6ECC94C |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Hylobates lar |

| status |

|

Lar Gibbon

French: Gibbon lar / German: \WeiRhandgibbon / Spanish: Gibén de manos blancas

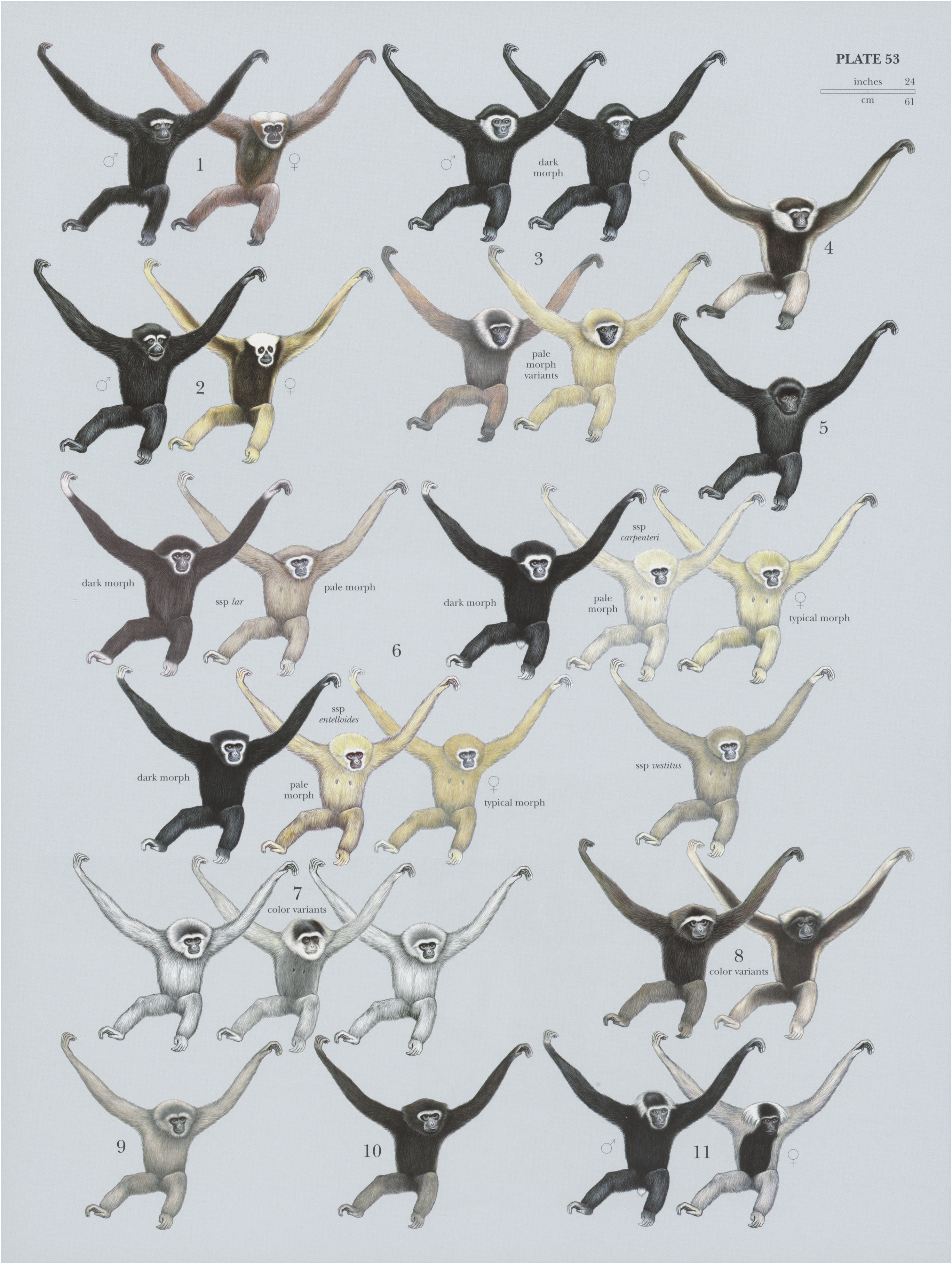

Other common names: Common Gibbon, White-handed Gibbon; Carpenter's Lar Gibbon (carpenter), Central Lar Gibbon (entelloides), Malaysian Lar Gibbon (/ar), Sumatran Lar Gibbon (vestitus), Yunnan Lar Gibbon (yunnanensis)

Taxonomy. Homo lar Linnaeus, 1771 .

Restricted by C. Kloss in 1929 to Malaysia, Malacca.

The various subspecies are not highly distinct and are based largely on relatively minor body color variation and the degree of polychromatism in the fur. The validity of yunnanensis as a distinct taxon is doubtful, and it is probably synonymous with carpenter. Some publicationsstill consider yunnanensis a valid subspecies, but this may be moot because populations of the taxon are probably extinct. This species forms a narrow zone of sympatry and hybridization with H. pileatus in Khao Yai National Park, central Thailand, and with H. agilis in the Malay Peninsula (human-induced by the creation of a lake in the 1970s), and it is broadly sympatric with Symphalangus syndactylusin the Malay Peninsula and north Sumatra. Five subspecies are recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

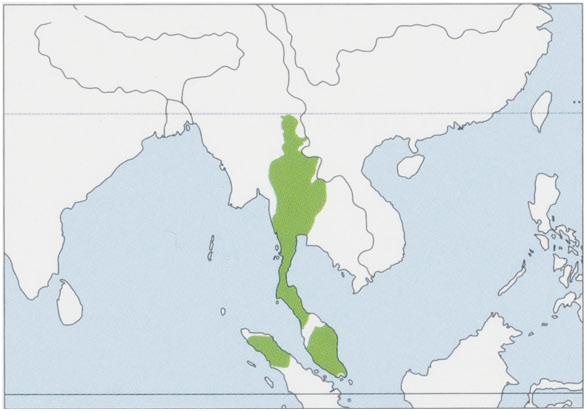

H. l. larLinnaeus, 1771 — MalayPeninsula, from 9 ° NtotheMudahRiverandSofthePerakRiver.

H. l. vestitusG. S. Miller, 1942 — NSumatra, NWofLakeTobaandtheSingkilRiver.

H. l. yunnanensis Ma & Wang, 1986 — S China (SW Yunnan Province), the northernmost subspecies, originally between the Nujiang (= Salween) and Lancangjiang (= Mekong) rivers in the counties of Cangyuan, Menglian, and Ximeng; by the 1960s limited to the Nangun River at elevations of 1000-1500 m, but now probably extinct there. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 41-4 cm (males) and 41-6 cm (females); weight 4.1- 7.3 kg (males, n = 43) and 3.9-6.1 kg (females, n = 37). These measurements and weights are taken from publications by A. Schultz in 1933 and 1973; weights are from the type series of the “Carpenter’s Lar Gibbon ” (H. Ll carpenteri) and may include some immature animals. Measurements from southern China “Yunnan Lar Gibbon ” (H. I. yunnanensis) were provided by S. Ma and colleagues in 1988: mean head-body length of four males and a female 49-9 cm (range 44.5-57.8 cm) and mean weight 7-2 kg (range 5.3-8.5 kg). In 1929, C. Kloss provided weights of the “Sumatran Lar Gibbon ” (H. I. vestitus): males 4.3-5.5 kg and a female 5-3 kg. The Lar Gibbon has two main color phases—dark (brown to black) and pale (creamy-fawn to reddish-buff)— that have no relation to age or gender, although the exact shading may vary by region. In museum collections, specimens of the Sumatran Lar Gibbon are fairly light brown (like the pale phase of the “Central Lar Gibbon ,” H. l. entelloides), and it would seem that the Sumatran Lar Gibbon does not show color polymorphism, but this needs to be confirmed in the wild populations. All Lar Gibbons have a naked black face encircled by a ring of whitish fur, with sharply contrasting white fur on uppersides of hands and feet. The crown hair is directed fanwise from the front of the scalp and is not elongated or laterally projected over the ears. Adult males have black tufted fur on the pubic region. Sexes are similar in size. Color is very variable in the Malay Peninsula (from dark brown to buff), but further north, individuals are either very dark (black) or very pale (creamy-fawn) with no intermediates; these extremes are not related to sex, unlike neighboring species of hoolock and crested gibbons.

Habitat. Lowland to dipterocarp forests; mixed deciduous bamboo forests; evergreen, semi-evergreen, and wet evergreen forests; and even peat-swamp forests, mainly below 1200 m above sea level. The Lar Gibbon prefers the upper canopy of undisturbed primary forests, but it also occurs in secondary and selectively logged forests. Average height of feeding trees of Lar Gibbons in Khao Yai National Park, Thailand,is 23-7 m.

Food and Feeding. Lar Gibbons feed on a large variety of foods. Figs and other small, sweet fruits are preferred, but young leaves, buds, flowers, new shoots, berries, vines, vine shoots, insects (including mantids and wasps), and bird eggs are also consumed. They are known to eat parts of more than 100 species of plants. Diet varies considerably with seasons; for example, in Khao Yai National Park, non-fig fruits dominate the diet throughout the year except in November-December. There, flowers are most available during the cool season, while ripe fruit is most abundant during the hot-wet seasons. Ripe fruit is preferred when available, with the diet being more diversified when ripe fruit is less available during the cool season. Fruit (including figs) never falls below 50% of the diet year-round. Overall, the average diet is composed of 66% fruit, 24% leaves, 9% insects, and 1% flowers. Lar Gibbons compete with sympatric Siamangs ( Symphalangus syndactylus ), the presence of which usually causes conflict and probably reduces the foraging success of Lar Gibbons. Food competition may also take place between Lar Gibbons and the Sunda Pig-tailed Macaque (Macaca nemestrina), because the two species have been seen foraging near one another and will sometimes interact, and also with Long-tailed Macaques (M. fascicularis) and Dusky Langurs (7Trachypithecus obscurus).

Breeding. The Lar Gibbon has a menstrual cycle of 21-2-22 days (range 15-25 days). In the wild, females reproduce for the first time when about eleven years old (range 9 years and nine months to twelve years and nine months). At a minimum, the interbirth interval is three years and averages 3-4 years. If a female loses a baby, she may ovulate again sooner, but the average interbirth interval in a population at carrying capacity is c.3-5 years. Females exhibit swelling, protrusion, and a change in the color of the sexskin beginning several days before ovulation and ending after ovulation, usually lasting c.7-11 days. Pregnant females also show sexual swelling at random times during pregnancy. Females start to show a conspicuous swelling of the vulva by the third month of pregnancy. Mating occurs in every month of the year, but most conceptions occur during the dry season (March). Sexual solicitation by the female involves her placing herself in front of a male and looking back at him, presenting her genitals. Copulation is dorso-ventral, with the male behind the female. Females may refuse copulation by moving away from the male, calling, or agonistically refusing his advances. Male-male mounting has been observed among wild male Lar Gibbons. Gestation is about six months in the wild. There are few observations of births and infant development of Lar Gibbons. At one studysite in Thailand, births showed a peak during the late wet season to early dry season transition in September—-October. Neonates weigh an average of 383-4 g and are almost entirely naked except for a cap of fur on the crown. They are able to call soon after birth. Parental care is given predominantly by the mother, although the father and eldersiblings also assist. In the wild, infants are carried clinging to their mother’s ventrum. Observations of one infant in the wild and of captive Lar Gibbons show that solid food is first ingested at four months of age. The wild infant also starts moving a short distance from its mother at that age. The ability to brachiate was first seen in a captive infant around nine months old. Infants are weaned at about 28 months old. Infant mortality is generally low, less than 10% in the first year oflife. Juveniles of both sexes reach adult size at aboutsix years of age, but they remain with their natal group until they reach sexual maturity at around 8-9 years. Generation length of Lar Gibbonsis c.15 years. They mature late, with females maturing at 8-10 years and males at 8-12 years, and have one offspring every 3-5 years. These data were obtained from a site, however, with a density of Lar Gibbons high enough to suspect that maturity was being delayed—perhaps a case of “saturated” habitat. They live for at least 40 years in the wild, but as long as 50 years in captivity.

Activity patterns. Lar Gibbons are diurnal and arboreal. On average, they spend their day feeding (33%), resting (26%), traveling (24%), engaged in social activities (11%), vocalizing (4%), and involved in intergroup encounters (2%), although actual proportions of activities can change significantly over the course of the year. Much of the day is spent foraging and resting. Lar Gibbons in Thailand are active for an average of 8-7 hours/day, leaving their sleeping sites around sunrise and entering sleeping trees an average of 3-4 hours before sunset. If the morning is clear before dawn, an adult male emits his solo calls, usually from his sleeping tree. At sunrise when all members of a group awaken, they defecate and urinate while hanging from a branch. The group then movesto a feeding tree. There is normally a duet call among the adult pair before noon, and the rest of the day is spent alternating between feeding and traveling to new trees to feed. With seasonal reductions in the amount of available fruit, feeding time increases and correspondingly less time is spent in social activities. The group usually pauses each day for about an hour of rest and social activities. Lar Gibbonstry to avoid notice when moving to sleeping sites, possibly as a way of reducing predation. Often the tallest trees available are chosen as sleeping sites,if possible located on steep slopes or cliffs. During the cool season, groups of Lar Gibbons can often be found in large fig trees for up to several hours a day.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. As a rule, Lar Gibbons live in serial monogamous pairs with up to four offspring in each group, but occasionally they are found in socially polyandrous groups (a female and two adult males); sometimes sexual relationships can extend beyond the mated pair (extrapair copulations), and polygamous mating has also been observed. Long-term data indicate that females may live in several different types of groups (e.g. pair or multimale) over their lifetimes. In the case of extrapair copulation by females, however, the frequency of copulation remains much higher with the pair-mate than with other males. Censuses at Khao Yai National Park from 1992 to 2007 recorded an average proportion of pairs of 76-9% (n = 120), with multimale—unifemale (polyandrous) groups accounting for 21-:2% (n = 33, groups with mature male offspring excluded). Unimale-multifemale groups are rare (1:9%), and in the single case recorded in Khao Yai, one of the females was a Pileated Gibbon ( H. pileatus ) and not a Lar Gibbon . In the case of individual pair-bonds, changes can result from desertion (often for another mate), replacement of one of a pair by a peripheral individual, or disappearance or death of one of the adults. Changes in pair composition can be common due to disease, shortage of food resources, and fragmented and isolated forests. Pair bonds are normally life-long. Average group size in Lar Gibbons generally increases with latitude, illustrating that group size is not a useful species-specific character in gibbons. This reflects a general trend of increasing birth rate with latitude found in many vertebrate groups. Average group sizes have been reported at 2-7-3-3 individuals in Peninsular Malaysia, 3-7 in central Thailand, and 4-4—4-9 in northern Thailand. Home ranges are 12-54 ha, averaging c.40 ha, with highs of 44-54 ha on the Malay Peninsula and c.16 ha in Khao Yai National Park. While home ranges of different groups often overlap, sometimes extensively, there is a core territory defended from other groups that averages 76% of the home range. Average daily movementis 1400 m, although there is considerable variation among study sites. Daily movements tend to increase with greater fruit availability. Group progressions at some locations are usually led by an adult male, while at other sites females lead and coordinate group movements. Males are mainly responsible for defending the group’s territory. Within-group social behavioris variable throughout the year, from almost a fifth of the activity budget to only a small percentage; there is more social activity at times when ripe fruit is abundant. The three main types of within-group social interaction are grooming, play (wrestling, chasing, and slapping and biting), and social contact, with grooming being the most common. Aggression is rare. In general, immature Lar Gibbons play more than adults. There are some indications that allogrooming serves more of a hygienic than a social function in Lar Gibbons and tends to be reciprocal. Encounters between different groups of Lar Gibbons can range from agonistic (physical altercations) to friendly (between-group playing or grooming). Most interactions between groups are agonistic, but they can be purely vocal and even neutral (both groups when they meet barely react to one another). Groups may also travel, feed, or rest together when they come into contact. Males are the principal participants in most territorial disputes, but females are sometimes approached by males during intergroup interactions. Disputes generally occur near boundaries of the home range when two groups can see each other. They typically last about an hour, and most intergroup interactions are accompanied by calls. Variability of the nature of interactions between neighboring groups may partly be the result of variable social and kin relationships between members. Nevertheless, intergroup interactions can be quite violent, and there is evidence that wounds incurred in territorial aggression have resulted in death. There is seasonal variation in the occurrence of intergroup encounters, and territoriality may function in resource defense. In one long-term study, males dispersed from their natal groups at about ten years of age and usually attained a territory by replacing a resident adult. Dispersal distances are usually c.1-2 territories from the natal territory, averaging 0-71 km in one population. Densities of Lar Gibbons range from 2-4 groups/km? in Ketambe Research Station, Gunung Leuser National Park, Sumatra, to 0-7-2-6 groups/km? in Kuala Lompat and Tanjong Triang on the Malayan Peninsula and 6-5 groups/km? in Khao Yai National Park.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red Lust. The status of each subspecies of Lar Gibbon is: lar , vestitus, and carpenter are Endangered, entelloides is Vulnerable, and yunnanensis is Data Deficient. The Yunnan Lar Gibbon has been declared extinct in China, but it may still survive in Myanmar. The major threats to Lar Gibbons are loss of habitat and hunting. They are hunted for subsistence and for the pet trade. Hunting pressure varies across the range, but they are hunted even within protected areas. They are traditionally hunted by hill tribes in Thailand, and increased forest fragmentation has increased hunting pressure there. In Sumatra, some local people have a religious taboo against hunting primates, including Lar Gibbons , but in some areas, taboos against hunting gibbons appear to be breaking down. Shifting agriculture and commercial plantations of oil palm are major causes of deforestation. Some protected areas (e.g. Nam Phouy Biodiversity Conservation Area in Laos) are threatened with road construction within their boundaries. This promotes forest clearing and strip development and increases fragmentation and access by hunters. In northern Sumatra, most of the lowland forests have been logged, and the threat of Ladia Galaska, a road network to link the west and east coasts of Aceh Province, means that much of the remaining forest is at risk. In most of its range, the Lar Gibbon is confined to protected areas (e.g. in Thailand, no significant populations survive outside them), but, in most countries, these areas are not well patrolled, even if they are well managed for tourism. Illegal use of forest products and poaching are common in most protected areas. In Thailand, the decrease in forest cover has caused increased hunting. Further survey work is needed to determine current population numbers in protected areas. Current estimates suggest that there are probably 15,000-20,000 Lar Gibbons in Thailand with several populations numbering in the thousands, although they are now very rare in the north. The largest Thailand population is in Kaeng Krachan National Park with 3000-4000 individuals; the Western Forest Complex may well have 10,000 individuals; there may be more than 1000 individuals in the western part of Khao Yai National Park, as well as in Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary and Nam Nao National Park. A few smaller populations survive in the south (e.g. Khao Sok National Park). In southern Peninsular Thailand and north-western Peninsular Malaysia, a few smaller, fragmented populations survive, perhaps together numbering in the low thousands. There are no recent or reliable estimates of the populations in the Tenasserim section of Myanmar, northern Sumatra, or the southern Peninsular Malaysia. There are also no reliable estimates for Laos, but there may be a few hundred Lar Gibbons in Nam Phouy Biodiversity Conservation Area. The nominate subspecies lar occurs in at least two protected areas: Krau Wildlife Reserve in Malaysia and Thale Ban National Park in Thailand. The Sumatran Lar Gibbon occurs in Gunung Leuser National Park in Indonesia. The Central Lar Gibbon occurs in Maegatha and Kaser Doo wildlife sanctuaries and Tanintharyi National Park in Myanmar; Kaeng Krachan, Khao Yai, and Khao Sok national parks and Thung Yai Naresuan and Huai Kha Khaeng wildlife sanctuaries in Thailand. This is probably the least threatened subspecies because ofits relatively extensive distribution and presence in the largest forest areas now in numerous parks and wildlife sanctuaries. Hunting pressure, however, isstill a problem in most areas, making it vulnerable to ongoing declines. West of the Mekong River in Laos, Carpenter’s Lar Gibbon persists in small forest patches in Nam Phouy Biodiversity Conservation Area, but it is hunted there. In Laos, populations outside Nam Phouy are small, isolated, and hunted, and nationally Carpenter’s Lar Gibbon is critically endangered. It also occurs in Nam Nao National Park and Phu Khieo and Huai Kha Khaeng wildlife sanctuaries in northern Thailand. The Yunnan Lar Gibbon was, until 1992, known to have occurred in just one protected area, Nan’gunhe National Nature Reserve in south-western Yunnan, China. Much of the forest in the Nan’gunhe is now degraded and secondary, inappropriate for Lar Gibbons , or has been converted directly to farmland. Surveys in search of this subspecies were carried out in 2008, and it was concluded that it had been entirely extirpated as a result of continued forest destruction, fragmentation, and deterioration and hunting. It is not known to occur anywhere else, but slim hope remains that there are populations in neighboring Myanmar.

Bibliography. Arnason et al. (1996), Barelli, Boesch et al. (2008), Barelli, Heistermann et al. (2007, 2008), Bartlett (1999, 2003, 2007, 2009a, 2009b), Berkson & Chaicumpa (1969), Blackwell (1969a), Boonratana (1997), Brandon-Jones et al. (2004), Brockelman (1985, 2004), Brockelman & Geissmann (2008), Brockelman & Srikosamatara (1993), Brockelman et al. (1998), Caldecott & Haimoff (1983), Carpenter (1940), Chivers (1977, 1978, 1980, 2001), Clemens et al. (2008), Dahl & Nadler (1992), Duckworth (2008), Edwards & Todd (1991), Ellefson (1974), Esseret al. (1979), Eudey (1991/1992), Fischer & Geissmann (1990), Frisch (1963, 1967), Geissmann (1984, 1991a, 1991b, 1995, 2007a), Geissmann & Orgeldinger (1995), Geissmann, Nijman & Dallmann (2006), Geissmann, Traber & von Allmen (2006), Gittins & Raemaekers (1980), Groves (1968a, 1968b, 2001), Grueter, Jiang Xelong et al. (2009), Guo & Wang (1995), Haggard (1965), Johns (1985b), Kawamura (1958, 1961), Kloss (1929), Lan & Wang (2000), Lao PDR, MAF (2011), Ma Shilai & Wang Yingxiang (1986), Ma Shilai et al. (1988), MacKinnon & MacKinnon (1977, 1980b), Marshall & Brockelman (1986), Nettelbeck (1998a, 1998b, 2003), Newkirk (1973), Palombit (1993, 1994a, 1994b, 1995, 1996, 1997), Raemaekers (1977, 1979), Raemaekers & Raemaekers (1984a, 1984b, 1985), Raemaekers et al. (1984), Reichard (1995, 1998), Reichard & Barelli (2008), Reichard & Sommer (1994,1997), Reichard et al. (2012), Roberts (1983), Roonwal & Mohnot (1977), Savini et al. (2008), Schultz (1933, 1973), Sommer & Reichard (2000), Tantravahi et al. (1975), Tenaza (1985), Ungar (1995), Vellayan (1981), Weigl (2005), Whitington (1992), Whitington & Treesucon (1991), Woodruff et al. (2005), Yimkao & Srikosamatara (2006).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.