Symphalangus syndactylus (Raffles, 1821)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6727957 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6728317 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D787BA-0E34-FFCD-FFEF-FC96F820C78B |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Symphalangus syndactylus |

| status |

|

19. View Plate 54: Hylobatidae

Siamang

Symphalangus syndactylus View in CoL

French: Siamang / German: Siamang / Spanish: Siamang

Taxonomy. Simia syndactyla Raffles, 1821 View in CoL ,

Indonesia, West Sumatra, Bencoolen (= Bintuhan).

Some authorities recognize the mainland and Sumatran populations as two distinct subspecies, continentis and syndactylus , respectively. Siamangs are sympatric with Hylobates lar on the Malay Peninsula and northern Sumatra and with H. agilis in southern Sumatra. Monotypic.

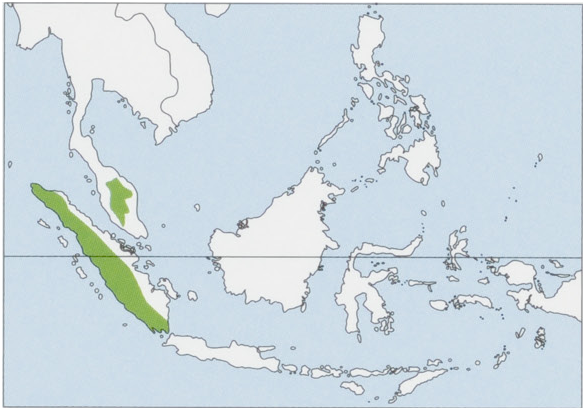

Distribution. Malay Peninsula in S Thailand (only in a small area on the border with Malaysia), NW & C Peninsular Malaysia (largely restricted to mountainous areas in the W of the country, S of the Perak River and N of the Muar River, and Tasek Bera across to the Pahang River), and W Sumatra where confined to the Barisan Mts; it may have formerly occurred on Bangka I. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 75-90 cm; weight 10.5-12.7 kg (males) and 9.1-11.5 kg (females). The Siamang has an intermembral index of 138-141. All age and sex classes have black pelage, although mature individuals may develop creamy hairs on the chin, and a white brow band occurs in a minority of individuals, mainly females. Siamangs have a large inflatable throat sac, the second and third toes are variably webbed (syndactylous), and males have a prominent genital tuft.

Habitat. Lowland, submontane, and montane forests, including dipterocarp forests. Siamangs can inhabit primary and secondary forests, including selectively logged forest, albeit at lower densities. Siamangs are found at higher elevations than sympatric gibbons, potentially facilitated by their larger size that aids in thermoregulation and a more flexible diet that can include higher proportions of leaves. Siamangs are commonly found up to 1500-2000 m above sea level and have been recorded up to 2300 m in Kerinci-Seblat National Park.

Food and Feeding. Siamangs are largely frugivorous, although less so than sympatric species of Hylobates . A large proportion of the diet is composed of figs ( Ficus , Moraceae ). Populations in Sumatra have higher levels of frugivory than those in Malaysia, potentially because of higher fruit availability and the inclusion of figs in the diet. Relative frequencies of feeding on different food types, with figures being averages taken from all studies on the species, are 42-:2% leaves, 32% figs, 12% fruit, 9-4% insects, and 4-4% flowers. Figs are particularly preferred in the early morning and late afternoon, which may represent a strategy to offset energy debt incurred during the night. While feeding, climbing is the most commonly used locomotion between food patches, and supports used during feeding are generally smaller than those used for travel. The relatively large forelimb to hindlimb weights, compared with other hylobatids, also suggest that the Siamang is specialized for forelimb climbing. Siamangs most commonly hang when eating fruit, suggesting that, despite being larger than other hylobatids, they are still adapted for terminal-branch feeding. They are sympatric with the smaller gibbon taxa, the Agile Gibbon ( H. agilis ) and the Lar Gibbon ( H. lar ), over much of their distribution and have a great deal of dietary overlap with them. All three species rely heavily on figs, but the Siamang supplements its diet with young leaves, while the two gibbon taxa supplement their diets more with pulpy fruits, avoiding competition to some extent. Siamangs often displace groups of Agile and Lar gibbons from preferred food sources.

Breeding. In captivity, adult male Siamangs breed as early as 4-3 years of age and females at 5-2 years, although reproductive maturity occurs more commonly at 8-9 years, as suggested by data on wild individuals. Copulation is usually dorso-ventral, but instances of ventro-ventral copulation have been recorded. The gestation period is 189-239 days. Births may be seasonal coinciding with high fruit abundance, but evidence is lacking to confirm this. A single observed wild birth suggests that females reduce their activities significantly in the days before giving birth. Generally, a single young is born; twins are rare. Neonatal weight averages 540 g (n = 46), with no difference between male and female neonates. Infants start taking solid food by 3-9 months of age, are largely weaned by twelve months, and completely independent when two years old. Interbirth intervals may exceed three years, based on limited longitudinal information from a few individuals, and, consequently, lifetime reproductive output is likely to be 5-10 offspring/female.

Activity patterns. Siamangs become active around sunrise and retire to sleeping trees ¢.16:00 h, with an average daily activity period of about ten hours. Sleeping trees may be centrally located in their territories. Calling usually occurs after dawn and generally after the first feeding bout of the day. One group’s calls inhibit the calling of other nearby groups, with groups taking turns. Calling may only occur on 30% of days, although this is highly variable and is possibly linked to times of peak availability of fruit and periods of reproductive activity. Unmated adult males sing solos. Based on several studies on both Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra, activity budgets can be summarized as dominated by feeding (35-50%) and resting (25-44%), with less time spent traveling (12-22%). Social activities, such as singing and calling, playing, and grooming are infrequent. Feeding and travel peak in the morning, with a steady increase in resting as the day continues. The majority of activity occurs in the middle and upper canopy. They use the lower canopy infrequently, feeding there sometimes in the heat of the day. Siamangs have a diverse locomotory repertoire while traveling, including brachiation (51%), climbing (37%), bipedalism (6%), and leaping (6%). Travel consists mainly of movement between food sources and sleeping trees, generally following frequently used arboreal highways. A Diard’s Clouded Leopard (Neofelis diardi) has been recorded taking a juvenile Siamang. Anti-predator behaviors may include sleeping in tall trees and forming mixed-species groups with langurs.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Home ranges of Siamangs are 15— 24 ha, often with some overlap between groups and sympatric Agile and Lar gibbons. Intergroup encounters at common territorial borders occur regularly. They involve calling by males and females, and males chasing males along the boundary. Daily travel distances are variable between groups, locations, and potentially season. They are 400— 3000 m/day, generally averaging 1000-1200 m. Females usually lead the group when traveling, with independent young following next, then the adult male, and behind them, adolescents. Groups are normally highly cohesive and contain 3-4-3-9 individuals. While usually monogamous, polyandry may occur, with a single female and two, usually unrelated, males. The role of polyandry does not appear to be related to the female’s need for additional help in raising infants because groups with two males collectively provide less parental care than those with a single male. Siamangs are unique among the Hylobatidae because males usually become the primary caregiver for infants during their second year of life. By carrying infants, males reduce female energy output during this phase of reproductive effort, leading to shorter interbirth intervals. At one site, turnover of mates appears to be common, with many instances of pairbond dissolution through individuals of either sex leaving their mate and transferring to other groups. As they mature, adolescents are peripheralized by the adult male and female, and by four years old, they may move behind the group and sleep in trees apart from the rest of the group until eventually they move on to establish a new territory. Dispersing males are evidently quite philopatric, whereas females appear to disperse more widely. Intragroup aggression is most commonly targeted at adolescents. Grooming usually involves the adult male as a member of grooming dyads, most commonly with adult females and subadult males. Duetting in Siamang likely improves pair bonding, although itis also probably a territorial advertisement. Population density is highly variable across studies, probably linked to habitat type, with 2:4-24-6 ind/km?. Preference, as seen under higher densities, may be for lowland and montane forests, with hill dipterocarp and submontane forest less preferred. Inverse relationships in densities among Siamangs and sympatric Agile and Lar gibbons in different habitat types have been noted in several studies, suggesting niche differentiation. Densities of Siamangs may decrease in a south-north cline in Sumatra.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. The Siamang is legally protected in Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. It is known to occur in at least ten protected areas: Hala Bala Wildlife Sanctuary in Thailand; Krau Wildlife Reserve, Fraser's Hill Forest Reserve, Gunung Besout Forest Reserve, and Ulu Gombak Wildlife Reserve in Malaysia; and Gunung Leuser, Kerinci-Seblat, Bukit Barisan Selatan, and Way Kambas national parks and West Langkat Reserve in Sumatra, Indonesia. It is threatened by habitat destruction and degradation caused by conversion for agriculture and other uses, logging, both legal and illegal, drought, and fire. Siamangs are hunted for pets and use in traditional Asian medicine. Populations are in decline and may be seriously affected by the large-scale loss of lowland forest habitats. One estimate placed the loss of Siamang habitat on Sumatra at 40% between 1995 and 2000. EI Nino/Southern Oscillation events leading to widespread fires (exacerbated by logging, which dries out the forest floor) have been implicated in increased infant and Juvenile mortality. Increasing frequencies of these events could result in mortality rates becoming higher than replacement rates. The Siamang is the most common gibbon in the pet trade in Indonesia; it is also commonly found in markets in Sumatra, Java, and Bali. Population estimates of wild Siamangs are lacking from all but Bukit Barasan Selatan National Park, which has 4876-6606 groups or ¢.22,390 individuals.

Bibliography. Aldrich-Blake & Chivers (1973), Brandon-Jones et al. (2004), Caldecott (1980), Chivers (1972, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1984, 1986, 2001), Chivers & Chivers (1975), Chivers & Raemaekers (1980), Chivers etal. (1975), Dal Pra & Geissmann (1994), Elder (2009), Fleagle (1976), Geissmann (1991a, 1999, 2003), Geissmann & Orgeldinger (1995), Geissmann, Nijman & Dallmann (2006), Gittins & Raemaekers (1980), Groves (1972), Kawabe (1970), Kloss (1929), Koyama (1971), Lappan (2007, 2008, 2009a, 2009b, 2010), Malone & Fuentes (2009), Medway (1969), Mootnick (2006), Morino (2010), Nijman (2005b), Nijman et al. (2009), O'Brien, Kinnaird, Nurcahyo, Igbal & Rusmanto (2004), O'Brien, Kinnaird, Nurcahyo, Prasetyaningrum & Igbal (2003), Palombit (1994a, 1994b, 1995, 1997), Raemaekers (1978, 1979), Smith & Jungers (1997), West (1981), Yanuar (2009), Yanuar & Chivers (2010), Zihlam et al. (2011).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Symphalangus syndactylus

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Simia syndactyla

| Raffles 1821 |