Pachycerina Macquart, 1835

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5733/afin.050.0207 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D3878A-FF97-CC4D-FE1C-7ABEFDA9FEC2 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Pachycerina Macquart, 1835 |

| status |

|

Genus Pachycerina Macquart, 1835 View in CoL View at ENA

Pachycerina: Macquart 1835: 511 View in CoL . Type species: Lauxania seticornis Fallén, 1820: 27 , by monotypy.

Diagnosis (Afrotropical taxa only):

Small ( ca 3–4.5 mm), yellow-brown lauxaniids with bulging, convex, partially translucent prefrons; two lateral black or brown spots on prefrons ( Figs 1–3 View Fig View Figs 2–4 ). Head yellow. Arista densely plumose (setulae short, black and closely appressed against stem), except P. pellocera sp. n. Postpedicel of antennae elongated, 3–4× longer than pedicel ( Fig. 3 View Figs 2–4 ). Scape long ( ca 2× length of the pedicel), expanding distally. Postfrons fairly strongly sloping. Anterior fronto-orbital bristles inclinate (incurved), posterior fronto-orbital bristle reclinate ( Fig. 2 View Figs 2–4 ). Posterior fronto-orbital bristle ca 0.7× length of inner vertical seta. Fronto-orbital bristle alveolus encircled by brown spot ( Fig. 2 View Figs 2–4 ), sometimes faint. Fronto-orbital plates may be infuscated. Ocellar spot conspicuous, black or dark brown, enclosing ocellar triangle ( Fig. 2 View Figs 2–4 ). Ocellar setulae minute and inconspicuous. Postvertical (postocellar) setae decussate, intersection high ( Figs 2, 4 View Figs 2–4 ). Supracervical setulae ca 20. Palpus clavate, orange with black apex. Palpus setulate, very long seta apically ( Fig. 3 View Figs 2–4 ).

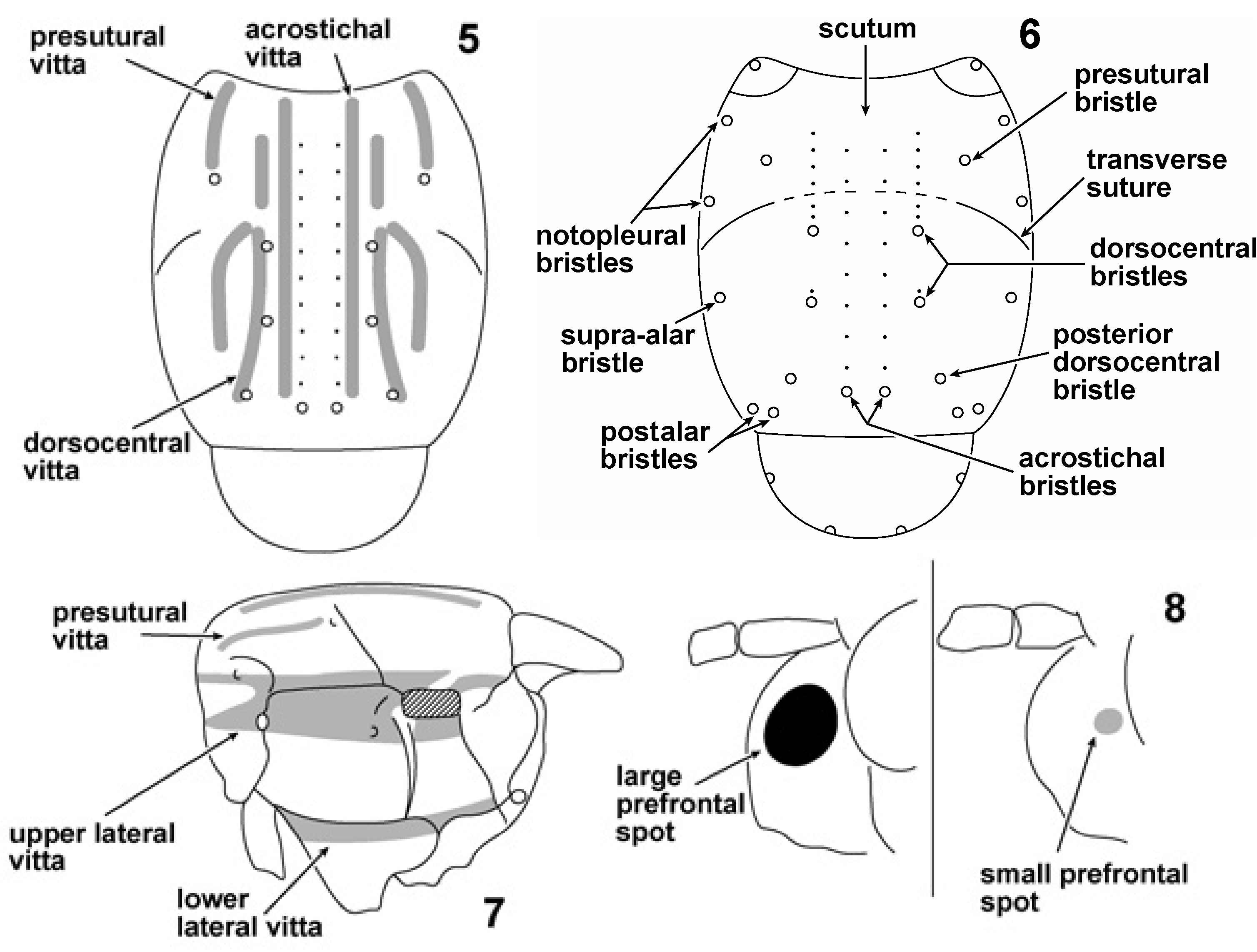

Lower edge of gena with pair of robust setae, the paired genal setae ( Figs 3, 4 View Figs 2–4 ). Thorax yellow-orange, usually with acrostichal, dorsocentral and presutural vittae dorsally and upper and lower lateral vittae on pleuron ( Figs 5, 7 View Figs 5–8 ). Acrostichals biseriate; 0+3 dorsocentral bristles, 1 or 2 setulae between anteriormost dorsocentral bristle and transverse suture, posterior dorsocentral bristle displaced laterally from longitudinal dorsocentral axis; anteriormost dorsocentral bristle is ca 60% length of posteriormost dorsocentral bristle; 1 humeral, 1 presutural, 2 notopleural, 1 supra-alar (+1 setula), 2 postalar (lower bristle much longer) bristles ( Fig. 6 View Figs 5–8 ); 1 mesopleural bristle (no setulae on sclerite); 1 sternopleural bristle (no setulae on sclerite). Scutellar posterior pair of bristles not decussate. Profemoral ctenidium absent. Front legs usually darker in colour than other legs. Three distinct rows of setae on posterior side of profemur, the posterodorsal, posteromedial and posteroventral profemoral setal rows ( Fig. 9 View Figs 9, 10 ).Anterior side of mesofemur with differentiated row of setae apically, the anteroapical mesofemoral row ( Fig. 10 View Figs 9, 10 ). Mesotibial preapical bristle more robust and apically placed than preapical bristles on other tibiae. Single mesotibial apicoventral spur, flanked by ca 9 robust setulae. Wing sapromyziform, stout costal setulae terminating ca 50 % of distance between apices of Vein 2 (R 2+3) and Vein 3 (R 4+5). Wing hyaline or partially fumose. Species with infuscated wings do not have clouded/shaded crossveins (cf. crossveins of Palaearctic P. seticornis ; Hendel 1907, pl. 3, fig. 50). Abdomen yellow to black, usually with two lateral black spots on T6 (in both sexes). Male terminalia, see separate section below. Female terminalia: S5 subquadrate, wider posteriorly than anteriorly, setulose. S6 short (in longitudinal plane), less than half length of S5, conspicuously narrower (in transverse plane) than S7, setulose. S7 fused to T7 (syntergosternite), sternal component of syntergosternite short but very wide (i.e. transversely elongated), much wider than other sternites, setulae along posterior margin. S8 subquadrate, setulose, setulae throughout sclerite. In repose, S8 curled, quasi-cylindrical. Hypoproct subovate, setulose. Cerci simple, setulose. Epiproct subovate, setulose. 2+1 spermatheceae. Egg white, elongate ovoid, slightly curved in lateral view, with ca 10 longitudinal ridges on chorion, weak transverse striations between ridges.

Male terminalia

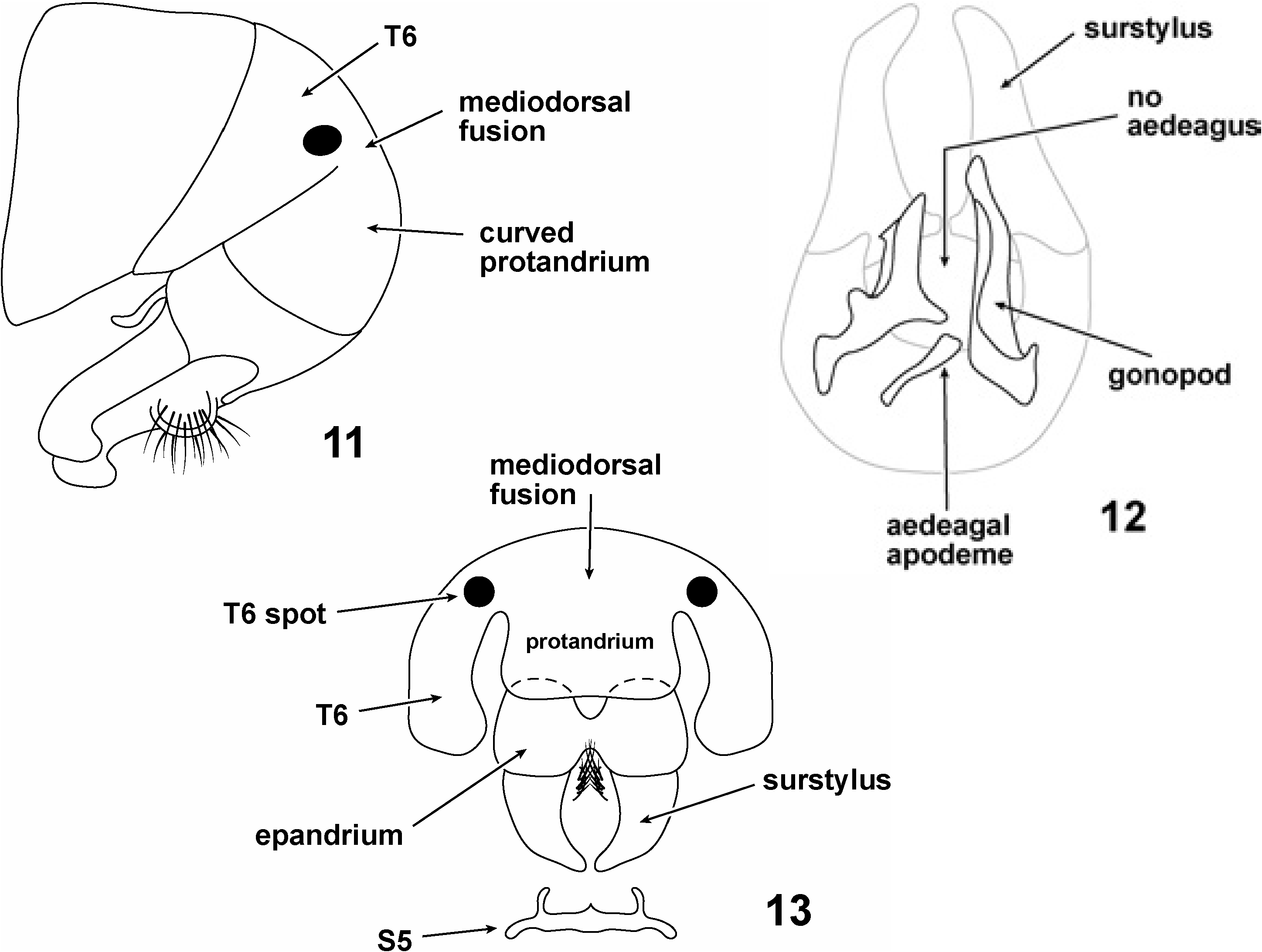

A separate, non-telegraphic section discussing the male genitalia of Pachycerina is felt appropriate.There are two especially notable features of Pachycerina male genitalia which we wish to discuss: (1) the partial fusion of the protandrium and T6, and (2) the absence of an aedeagus and hypandrium ( Figs 11–13 View Figs 11–13 ).

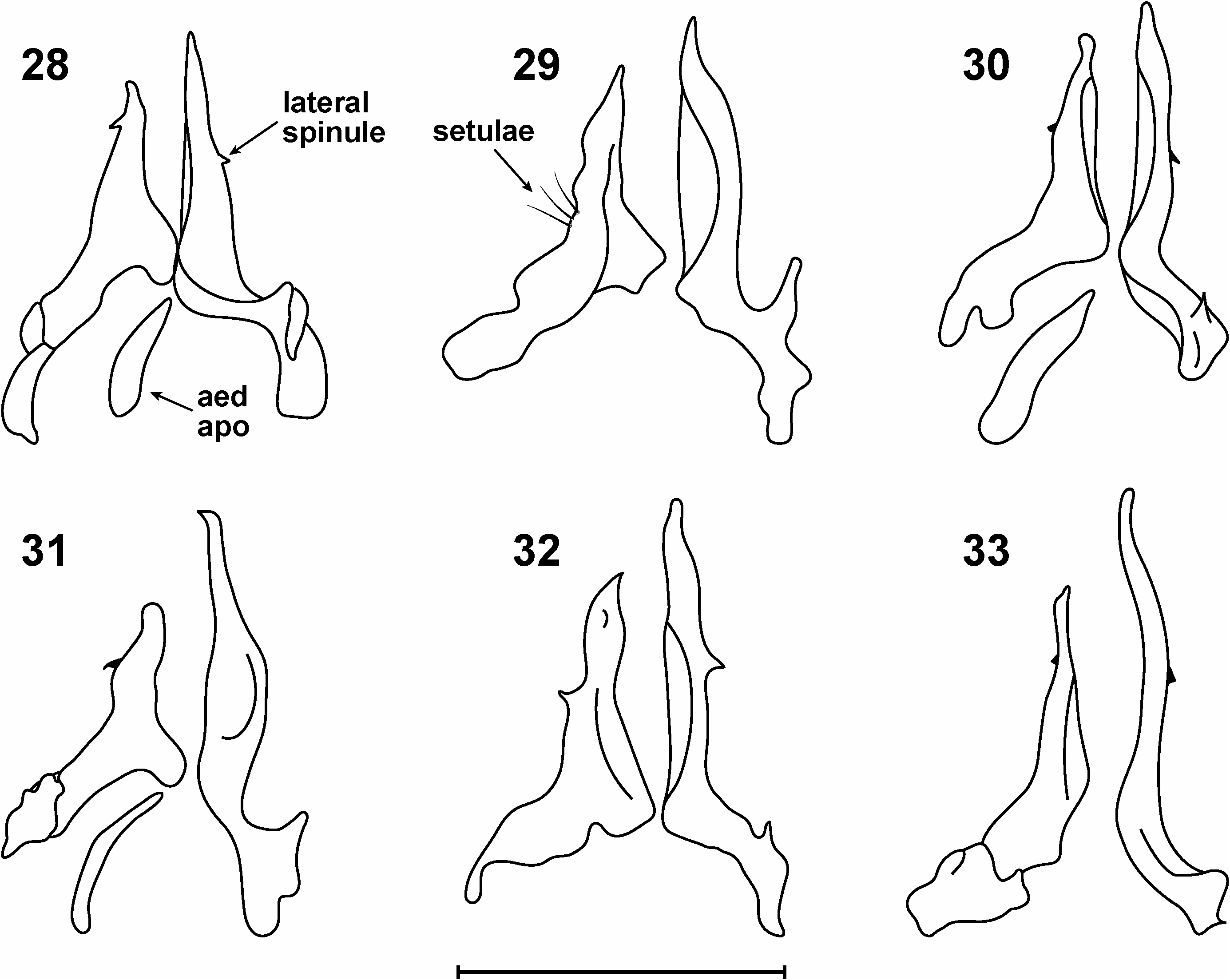

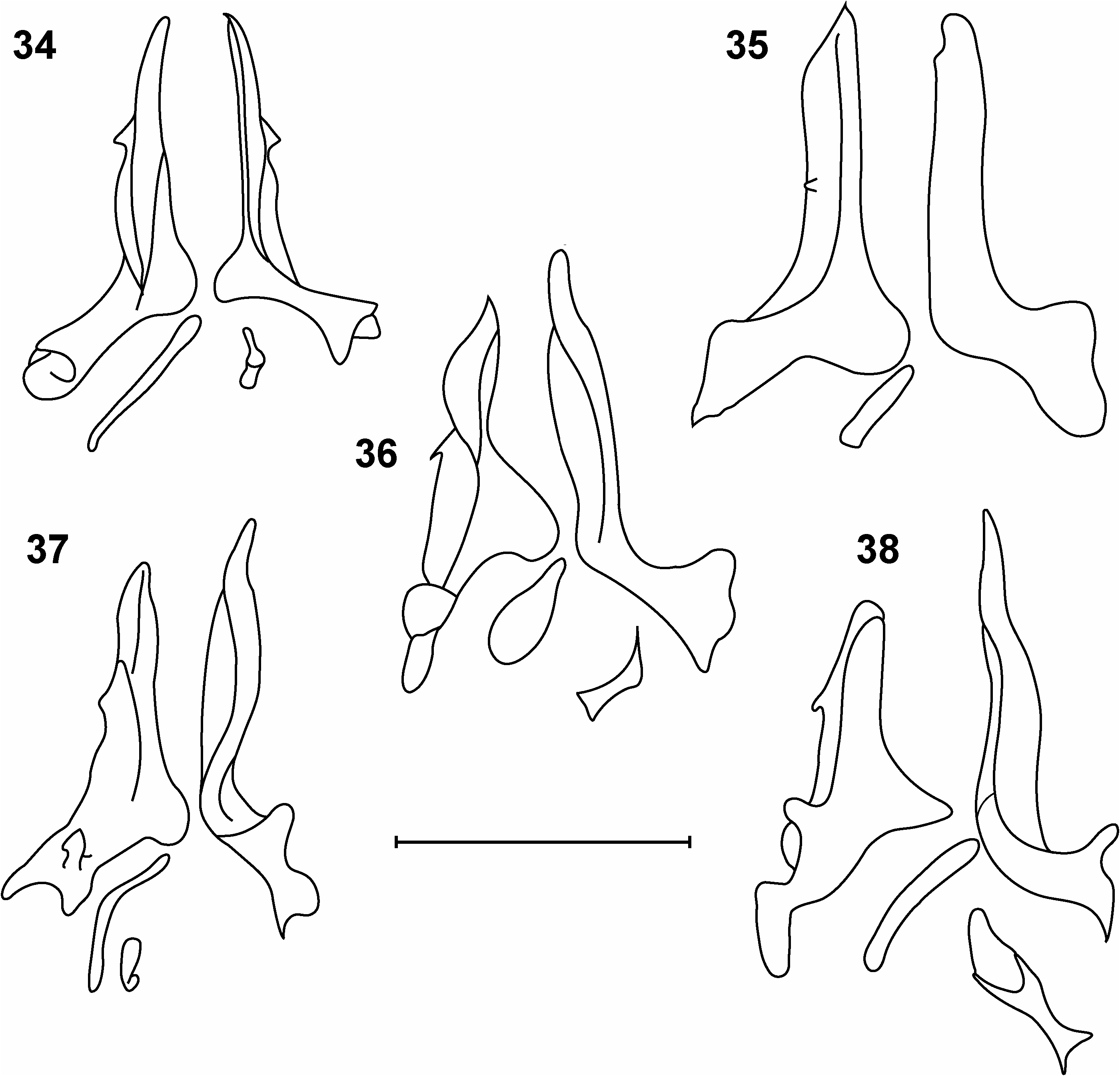

Generally speaking, the terminalia are composed of articulated, finger-like surstyli, reniform epandria, hirsute cerci and modified protandria ( Figs 11, 13 View Figs 11–13 ). Internally the genitalia are much simplified relative to other lauxaniid genera; on dissection of inner genitalia one sees two, asymmetric lobes with a short apodeme lying basally ( Fig. 12 View Figs 11–13 ). Our interpretation is that these lobes are gonopods, and the apodeme is the aedeagal apodeme. Shatalkin (1995) calls the gonopods ‘parameres’ in Palaearctic Pachycerina ; we have merely followed Stuckenberg (1971) and Kim (1994) in labelling them gonopods. The gonopods taper to pointed or rounded apices; they are medially scalloped (hollowed) and show species-specific shapes, most species bearing small spinules or mucros laterally. The gonopods are usually of unequal length, one gonopod exceeding the other in length, sometimes markedly (e.g., P. atrimela , Fig. 31 View Figs 28–33 ), but they may be equal in length (e.g., P. nigrivittata , Fig. 34 View Figs 34–38 ). There is no evidence of a distinct hypandrium in any male dissected and the sclerite is presumably absent, although it is conceivable that the hypandrium has become fused to the base of the gonopods, which extend out laterally as fairly pronounced flanges.

The aedeagal apodeme in Pachycerina is a simple, laterally compressed, longitudinal structure with no spinules or ornamentation and articulates loosely with the medial base of the gonopods. The ejaculatory apodeme is a small, ‘L’-shaped structure having a slightly expanded anterior terminus; it usually lies above the base of the gonopods.

Although not typically included under terminalia, we found the male S 5 in Pachycerina to be variable and to often show species-specific shapes. In most instances, S5 has been reduced to a narrow band with a small medial spur or mucro and two processes projecting posteriorly from the sublateral corners of the band ( Fig. 13 View Figs 11–13 ).

Fusion of protandrium and sixth tergite

In all Afrotropical species of Pachycerina the protandrium (= combined abdominal segments 7 and 8) is fused to T6 mediodorsally ( Figs 11, 13 View Figs 11–13 ), and strongly curved such that the epandrium, surstylus and inner genitalia are nestled under T4–T6 ( Fig. 11 View Figs 11–13 ). In all Afrotropical Pachycerina protandria the ventral portion of the sclerite has been lost.

Aside from merely counting the abdominal tergites (beginning with the syntergite 1+2), our identification of the protandrium is corroborated by what we interpret to be the 7 th spiracle in the sclerite preceeding the epandrium. If our identification of the abdominal segments is correct, then Pachycerina represents an apparent deviation from the characteristic that Hennig (1948: 407) first identified in lauxaniids, viz. that the 6 th tergite is not associated with the postabdomen (‘in der allgemeinen Gliederung des Abdomens der Lauxaniidae fällt zunächst auf, dass das 6 Abdomindalsegment nicht in den Komplex des Postabdomens einbezogen ist’). We have attempted to illustrate the situation as lucidly as possible so that other dipterists can form their own conclusions. Potentially, a partially fused T6 and protandrium may be an apomorphy of Pachycerina , or at least a subclade of the genus.

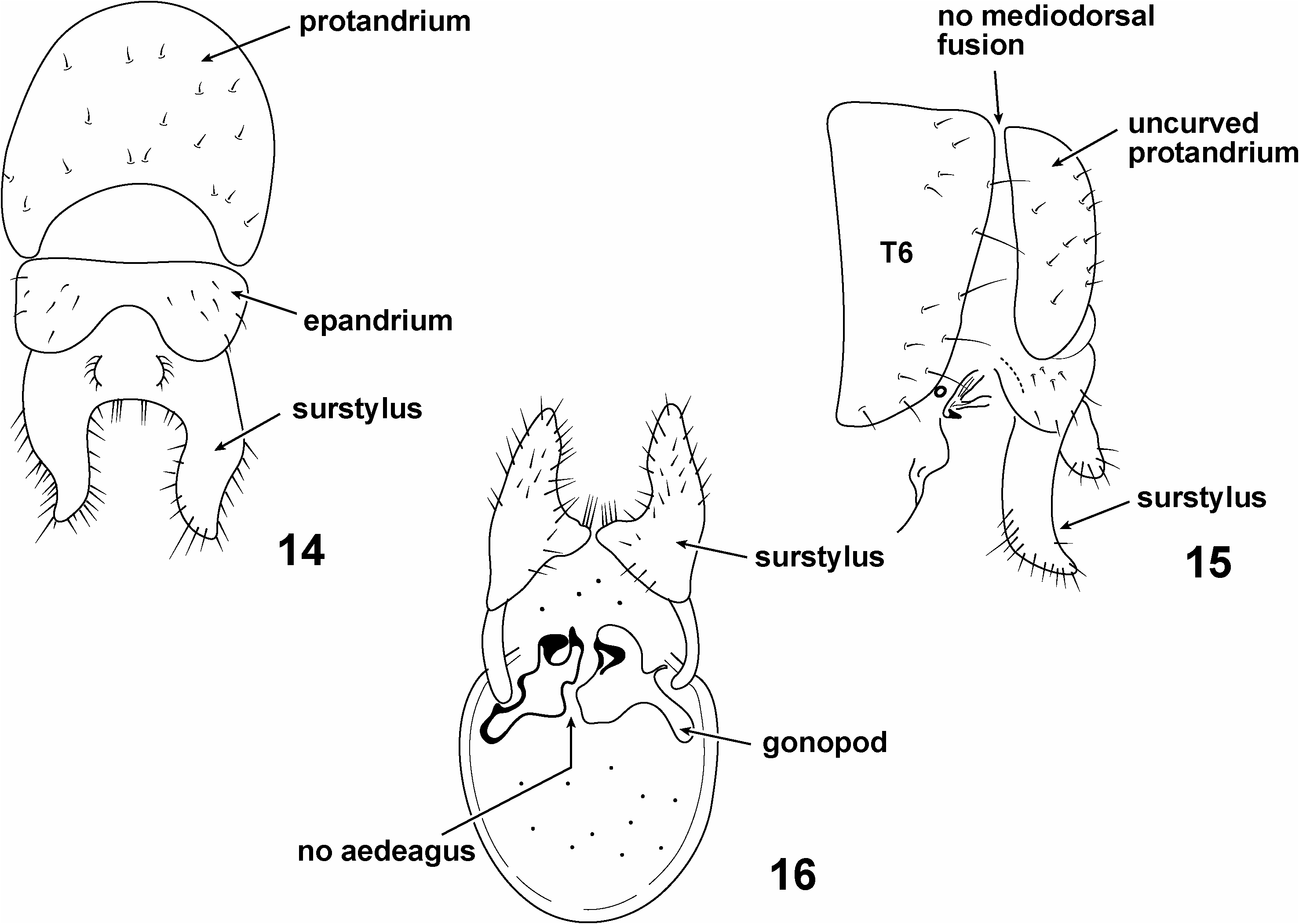

Unfortunately, no guidance can be found in the Palaearctic literature on the fusion of T6 and protandrium. Remm and Elberg (1979) gave two relevant illustrations of P. seticornis (recall that this is the type species of the genus) reproduced here as Figs 14– 16 View Figs 14–16 , which show the male terminalia in dorsal, lateral and ventral views respectively. They illustrate a large, crescent-shaped protandrium (identified as such in their figure caption) unattached to any preceding sclerite ( Figs 14, 15 View Figs 14–16 ). Their lateral view ( Fig. 15 View Figs 14–16 ) shows a large T6, a narrower protandrium and a ventrally placed ‘hypopygium’ (all these structures are identified as such in their figure caption). No connection between T6 and the protandrium can be seen in their figure, and furthermore the protandrium is not strongly curved. Their text does not discuss the Pachycerina male terminalia ( Remm & Elberg 1979: 66–69).We take their illustrations to show that (1) the T6 and protandrium are not fused mediodorsally in P. seticornis , and (2) the protandrium lacks any strong curvature.

Shatalkin (1995, figs 6, 7; 2000: 74) is the only other researcher to have figured male terminalia of Palaearctic Pachycerina . His illustrations of P. ninae Shatalkin regrettably, however, omit the protandrium and preceeding tergites, and thus one cannot form any opinion on their structure; his text also does not comment on these structures. We have not found any illustrations or discussion of the male terminalia of Oriental species in the literature.

Stuckenberg (1971: 504) called attention to the variation he had observed in the structure of the protandrium in lauxaniids and observed that ‘differences in development, exposure and vestiture of the protandrium do not appear to have been used in lauxaniid taxonomy’. The situation in Pachycerina would appear to suggest the shape of the protandria may have phylogenetic value in elucidating relationships amongst lauxaniids. Stuckenberg did, however, illustrate intrageneric variation in the structure of Cestrotus Loew protandria ( Stuckenberg 1971, figs 3, 4 and 7), principal differences concerning the ventral development of the sclerite.

Loss of aedeagus and hypandrium

In all Afrotropical Pachycerina species we did not observe any aedeagus (sclerotised or membranous) and nothing that could be identified as a hypandrium ( Fig. 12 View Figs 11–13 ).

The absence of an aedeagus in Pachycerina was a somewhat surprising discovery. The only other possibility is that treatment with KOH may have obliterated the aedeagus and hypandrium during extractive treatment, but we discount this as a cause because (1) the same result was achieved for all Pachycerina males we dissected and (2) Shatalkin’s (1995) and Remm & Elberg’s (1979) diagrams are similarly without any structures that could be called an aedeagus or hypandrium (e.g., Fig. 16 View Figs 14–16 of P. seticornis ). They did not, however, comment on the absence of these structures.

Interestingly, amongst other lauxaniids, the aedeagus is also absent in certain Minettia Robineau-Desvoidy species and celyphid (beetle fly) genera ( Tenorio 1969: fig. 1; 1972: 371). Could this absence of an aedeagus be indicative of phylogenetic relationship, or is it a convergent resemblance? J.F. McAlpine (1981: 53) also reported similar instances in Amiota Loew (Drosophilidae) , Dasiops Rondani (Lonchaeidae) , and some Piophilidae . If these flies lack an intromittent organ, how is sperm transferred during copulation? We are not familiar with the literature on the evolution of mating organs in Diptera , but the disappearance of the aedeagus in unrelated acalyptrates hints at some unusual biological phenomenon, perhaps mediated by sexual selection?

Discussion of male genitalia

To recapitulate, the male inner genitalia of Afrotropical Pachycerina are simplified, lacking a hypandrium or aedeagus and having only a pair of contorted, asymmetric lobes (usually bearing spinules) and a rod-shaped apodeme basad of these lobes ( Figs 11–13 View Figs 11–13 , 16 View Figs 14–16 ). The protandrium is partially fused to the T6 (in Afrotropical species, at least), and this may represent a phylogenetically important modification not shown by any other lauxaniids.

General comments

Pachycerina is one of the more easily recognized lauxaniid genera in Africa, and is unlikely to be confused with any other lauxaniid genus. To briefly summarise, features of the African Pacycerina that are immediately striking include: (1) tiny ocellar setulae (‘ausserordentlich klein’ [extraordinarily small] in Becker’s (1895: 250) words), (2) incurved anterior fronto-orbital bristles (reclinate in most Afrotropical lauxaniids, except Chaetolauxania Kertész ), (3) bulging prefrons and lateral black spots (other Afrotropical lauxaniid genera lack such a tumid prefrons and maculation), (4) elongated postpedicel, (5) two acrostrichal bristle rows on mesoscutum, (6) no profemoral ctenidium, (7) usually dark brown protibia and protarsi (relative to yellow meso- and metatibiae and tarsi), (8) the presence of paired black spots on T 6 in some species, and (9) the absence of an aedeagus in the male of all species.

The Afrotropical Pachycerina fauna forms a small, compact and morphologically uniform grouping. In the Palaearctic and Oriental faunae it is notable that there seems to be more variability in coloration and morphology. For example, species in these other biogeographic provinces may have white aristae, single prefrontal spots or even lack the prefrontal spots entirely (see Malloch 1929: 20; Shatalkin 2000: 36–38 for further details). The most divergent Afrotropical species have an all-black abdomen (e.g., P. atrimela sp. n.) or reduced prefrontal spots ( P. micropunctata sp. n.).

Most of the Afrotropical species (e.g., P. vaga Adams , P. seychellensis Lamb ) appear most similar (phenotypically-speaking) to the Oriental P. javana Macquart. Indeed those Afrotropical species without a black abdomen run easily to P. javana in Malloch’s (1929) Oriental key. We are not necessarily implying phylogenetic propinquity with these comments, although such resemblance, faute de mieux, is suggestive of close relationship.

Within the Afrotropics, the Malagasy Pachycerina micropunctata sp. n. is immediately distinguishable from the remainder of the Afrotropical fauna by the tiny, brown prefrontal spots ( Fig. 8 View Figs 5–8 ). In the other Afrotropical taxa, these spots are distinctly larger and black ( Fig. 8 View Figs 5–8 ). Our personal knowledge of the Pachycerina fauna in other biogeographic provinces is very limited, but it is interesting that P. sexlineata de Meijere from Java, Indonesia was described as having tiny, pale brown prefrontal spots ( de Meijere 1914: 235; Malloch 1929: 20). De Meijere (1914: 235–236) also described Pachycerina parvipunctata de Meijere as having small prefrontal spots, although in this case the spots were black. Both P. sexlineata and P. parvipunctata , however, have the aristal setulae described as ‘not dense, erect, and the longest very distinctly longer than basal width of third antennal segment’ ( Malloch 1929: 20), a feature not in accord with P. micropunctata . The postabdomens of these two Asian species do not appear to have been illustrated or described in the literature. It is possible that P. micropunctata could be closely related to these Asian species, speculation that can only be corroborated once the necessary postabdominal dissections of these Oriental taxa have been undertaken and a phylogeny for the whole genus constructed. There are examples in Diptera where a Malagasy species appears to have a sister-species, or at least a close relative, in the Orient, e.g., Chrysopilus rhagionids (Stuckenberg 1997: 235).

Life history data

Unsurprisingly, there is little biological data on these inconspicuous flies. However, RMM reared two specimens of P. vaga from ground-nesting bird nests (probable Cisticola species ( Sylviidae )) collected in Bisley Valley, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. The habitat was dense Acacia grass-savannah on the sides of a stream. The bird nests were collected in December 1978, and the adult flies emerged in January 1979. RMM also reared an adult P. vaga collected as a puparium from leaf-litter in February 1977 at Drummond, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa; the fly emerged during the same month. There are no recorded rearing records for Palaearctic Pachycerina .

From these scraps of data, it is probable that Afrotropical Pachycerina are detrivorous or saprophagous in the larval stage, as with other lauxaniid larvae ( Miller 1977), but possibly specializing on bird nests or other restricted microhabitats. Miller (1977, table 1) summarized the lauxaniid taxa known to have been reared from bird nests in the Northern Hemisphere. Records of nidicolous species were noted for the following genera: Calliopum Strand , Lyciella Collin , Minettia Robineau-Desvoidy , Poecilominettia Hendel , Pseudocalliope Malloch and Sapromyza Fallén. It is possibly of significance that these genera are all in the subfamily Lauxaniinae , as is Pachycerina .

The hyper-extended postpedicels of Pachycerina are indicative of some special sensory requirement. In discussions between the two authors, we mooted that possibly such elongated postpedicels were required for finding a restricted or localized microhabitat for oviposition (such as bird nests), but the nidicolous genera discussed in the previous paragraph generally do not have elongated third antennal segments. Possibly then the elongated postpedicels serve to find some localized microfungi that adults graze? This is based on the assumption that the adults are fungivorous grazers, although Pachyopella ornata (Melander) was found to be a liquid-feeder by Broadhead (1984). We have not yet investigated the proboscides of Pachycerina with Scanning Electron Microscopy. Whatever the case, hyper-extended postpedicels, which are also notable in genera such as Lauxania and Melanomyza (e.g., Shewell 1987, figs 87.13 and 87.16), call out urgently for a functional explanation.

In our experience, Pachycerina occurs at low densities. For example, in Acacia savannah at Bisley Valley, Pietermaritzburg, sweeping the herbage often only results in the capture of 1 or 2 Pachycerina per hour of sweeping; this contrasts with other lauxaniid genera that may co-occur in the same habitat such as Mycterella Kertész , which may be locally common. This scarcity is also reflected in Malaise trapping. Quite a large number of Pachycerina specimens have been collected in Malaise traps (see material examined for P. vaga ), but when present Pachycerina is only represented by a few specimens (in KwaZulu-Natal, both P. vaga and P. nigrivittata have been caught in Malaise traps set by RMM in open thornbush and forest edge).

In South Africa, Pachycerina has been swept from Isoglossa herbage in the understorey of coastal, subtropical forest, from the understorey of high-altitude (> 1500 m) Podocarpus forest, in thick grass and shrubs under shade along a seepage line, and in thick shaded shrubbery in Acacia savannah and sub-montane, temperate (mist-belt) forest. In Madagascar, most records come from the (formerly) forested east-facing escarpment; according to label data, P. atrimela sp. n. having been swept along paths in the lush rainforest at Andasibe (Périnet) and Amber Mountain ( Antsiranana). In our experience, the genus has a preference for shaded areas under trees.

A series of P. seychellensis collected on Silhouette Island, Seychelles were all captured at a light trap. Specimens of female P. vaga and P. nigrivittata from Maguga, Kenya were recorded as having being collected ‘at light’ and a female P. nigrivittata from Howick, South Africa was taken at ‘domestic lights’. These records indicate some attraction to lights (phototaxy) in the genus, which is also corroborated by Greve and Kobro’s (2004) report of catching 35 specimens of P. seticornis at light funnel traps in Norway.

From species with sufficient specimen records such as P. vaga , there does not appear to be any strong seasonality as specimens have been caught throughout the year, even in the dry and frequently cold austral winter. Supporting this fact, in northern Europe, P. seticornis was found to regularly occur on snow throughout the frigid Norwegian winter ( Hågvar & Greve 2003: 414)!

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Pachycerina Macquart, 1835

| Davies, Gregory B. P. & Miller, Raymond M. 2009 |

Pachycerina : Macquart 1835: 511

| MACQUART, J. 1835: 511 |

| FALLEN, C. F. 1820: 27 |