Cortaderia selloana (Schult. & Schult.f.) Ascherson & Graebner (1900: 325)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.596.1.1 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7918081 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03BF87F0-CEFF-0BAE-66C8-D27BFD64AAE4 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Cortaderia selloana (Schult. & Schult.f.) Ascherson & Graebner (1900: 325) |

| status |

|

Cortaderia selloana (Schult. & Schult.f.) Ascherson & Graebner (1900: 325) View in CoL View at ENA .

Basionym: Arundo selloana Schultes & Schultes (1827: 605) View in CoL .

Type :— URUGUAY . Prope Montevideo, s.d. [1821–1822], Sellow ☿ d 396 (lectotype designated by Conert 1961: 87, as holotype: B 10 0185655!; with original labels by K. Sprengel, Nees von Esenbeck and Sellow; annotated by Conert as Holotypus von Arundo dioeca Spreng. non Lour.; isolectotype FR0031310 ! [fragm.]) . Probable syntypes : B 10 0185657!, Sellow ♁ s.n., with original label by K. Sprengel , K000308151 !, LE!, SGO000000186 About SGO !, US 00139587! & US 01257653!.

Replaced name: Arundo dioeca Sprengel (1825a: 361) , nom. illegit. non A. dioica Loureiro (1790: 55) ≡ Cortaderia dioeca (Spreng.) Spegazzini (1902: 194) , nom. illegit. superfl. ≡ Gynerium dioicum (Spreng.) Dallière (1874 : t. 42), nom. illegit. superfl.

Heterotypic synonyms: Gynerium argenteum Nees von Esenbeck (1829: 462) , nom. illeg. superfl.

Type:— URUGUAY. Prope Montevideo, s.d. [1822], Sellow ♀ d 570 ( lectotype designated by Conert 1961: 87, as Typusmaterial : B 10 0217509!; with original labels by Nees von Esenbeck and Sellow; annotated by Conert as Typusmaterial von Gynerium argenteum Nees ; isolectotypes BAA00000710 About BAA !, LE!, US 01257653!) . Probable syntypes: B 10 0185658! & BAA00000711 About BAA !, Sellow s.n., ex Herb. Kunth, B 10 0185655! & FR0031310 !, Sellow ☿ d 396.

Moorea argentea (Nees) Lemaire (1855: 14) View in CoL , nom. illegit. Cortaderia argentea (Nees) Stapf (1897: 396) View in CoL , nom. illegit.

Other possible syntypes of Arundo selloana View in CoL and/or Gynerium argenteum View in CoL : B 10 0185656! ( Sellow s.n., sterile), BAA00004670! ( Sellow s.n.), BM000031197! ( Sellow s.n.), P02656911! & P02656912! ( Sellow s.n. = Herbier Impérial du BRÉSIL N.o 224).

This example again illustrates how rich B was in Sellow specimens, for which botanists had access to more than single specimens (Sprengel, Nees von Esenbeck, et al.). There is more than one Sellow specimen annotated by both Sprengel and Nees von Esenbeck, establishing them as syntypes of these names. Considering this, given the lack of greater information about the collections in the protologues, typifications performed by Conert (1961, as holotypes) should be corrected to lectotypes (ICN Art. 9.10; Turland et al. 2018). That of C. selloana proposed by Testoni & Linder (2017) is thus superfluous (ICN Art. 9.19, Turland et al. 2018), under the claim that “Curiously, Conert (1961) proposed Sellow 396 from Brasilia as holotype of A. dioica , although Sprengel explicitly mentions that the type is from Monte Video,” which demonstrates that these authors were unaware of other Sellow collections. In addition, Testoni & Linder (2017) claimed that “ Gynerium argenteum Nees is also based on the same collection as Arundo dioica Spreng. , plus some additional material. All three names are based on the same type”, which is not strictly true. The typifications in Testoni & Villamil (2014) are also partially correct considering the above.

Regardless of whether Sellow’s specimens are nomenclatural types, knowledge of their numbering is essential for establishing locations and dates of their collection. Unfortunately, this remains a problem because this information is obscure and difficult to locate, even when it is glaringly obvious on the specimens in question. As mentioned above, prior to my stay in 2017, I tried to uncover virtually all Sellow labels on P specimens. During my 2017 visit, all labels that were hidden or face down in the digitised images were checked and their numbers annotated. Specimens of Ludwigia hexapetala ( Hooker & Arnott 1833: 312) Zardini et al. (1991: 243 ; P05100699) and Ludwigia peploides subsp. montevidensis ( Sprengel 1825b: 232) Raven (1963: 395 ; P05323782), however, were located after my visit and their Sellow’s original label information, which is on their undigitised reverse sides, is unknown to me.

For B specimens distributed to other herbaria, their respective numbering on the labels does not always correspond to Sellow numbers in his itineraries. Eugenia stigmatosa Candolle (1828: 268) , Berg (1857: 252) cited the following collection by Sellow s.n.: nec non in monte Cubatâo prov. S. Pauli , floret Martio. Among the specimens located, P05322198 (ex Herb.Al. de Bunge) is annotated with Sellow 5929, Cubat„o, 16 May 29 ( Fig. 44 View FIGURE 44 ), on which the collection numbering (upper left corner of the label covered by the specimen), is consistent with information about itinerary IV, in 1829 when he toured the Serra de Cubat „o, Serra de Santos and Santos, May –June. Other Myrtaceae specimens are also consistent with the collection number vs. locality indicated by Berg, namely: Sellow 5797 (LE00007022), Aulomyrcia apiocarpa Berg (1857: 64) , May–June 1829; Sellow 5842 (BM000799595, K000170018, LE00007440, P01902671), Eugenia oblongata Berg (1857: 302) , ad urbem Santos; Sellow 5938 (BR0000005261260, F0065428F, LE00007124, P00161489), Myrcia acuminatissima Berg (1857: 167) , ad urbem Santos. However, the month indicated by Berg is March, not May as on the P specimen. This refers to another collection, therefore, which was made during itinerary III, when Sellow visited Cubat„o, February–April 1820. Among the other Sellow specimens of the species, V0065326F (fragment ex P), K000276494 & P05322197 ( Sellow 272), S05-3051, U1442573 & W0070744 ( Sellow s.n.), Sellow 272 would likely be the specimen collected in March 1820 and cited by Berg.

As indicated by Urban (1893, 1906) and Herter (1945), the itinerary III specimens were numbered by Sellow with two series of numbers, preceded by B and c. However, Sellow’s B Myrtaceae were all destroyed, and the distributed B specimens generally lack the collection number or have otherwise incomplete information. Thus, Sellow 272 may be either Sellow B 272 or Sellow c 272, where one of the numbers of the other series is missing. Sellow’s Myrtaceae in the itinerary III specimens, distributed by B rarely show both numbers preceded by the letters. There are those where the double numbering is indicated without the letters, e.g., Sellow 149 1065 – Myrcia klotzschiana Berg (1857: 169 ; V0065503F, P00163111), or with only one of the numbers without the letters (BR0000005280964, P00163112, W0033296, Sellow 149); Sellow 1608 1054 – Gomidesia miqueliana Berg (1857: 24 ; K000565004, P 02272975); Sellow 1068 1626 – Eugenia umbelliflora Berg (1857: 290 ; V0065355F, LE00007525, P01902721). Among the itinerary III specimens of other families, collected in Cubat„o are Sellow B 1363 c 394 – Persea obovata Nees & Mart. (B 10 0185210, B 10 0185212 [F neg. 3575; F0061760F, fragment], K000602078, UVMVT001563; B 10 0185211, only with label 1363; G [2x], GZU000249335, HAL0103842, Sellow s.n.) ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ); and Sellow B 2182 c 2179 – Begonia angularis var. angustifolia Candolle (1861: 359 ; B 10 0124282, B 10 0124283).

For Eugenia stigmatosa View in CoL , two Sellow specimens were located at R:one mounted with the original Imperial Herbarium label, Eugenia/S. Paulo 725 (R [165458]), for which the specimen with the same HIB number at P (P05260106) is Myrcia venulosa Candolle (1828: 250) View in CoL ; a second specimen was mounted with original label from Imperial Herbarium, Eugenia / Rio Grande 1359 (R [165459]), for which there is a specimen with the same number at P (P05204064), which is Campomanesia aurea Berg (1857: 454) View in CoL , indicating possible labelling confusion.

Although not part of the main objective of this research, verification of the typifications involved was necessary to determine correct names of the taxa. In this process, several inaccuracies were detected, e.g., typification of Glandularia selloi (Spreng.) Troncoso (1964: 481) View in CoL ≡ Verbena selloi Sprengel (1825b: 750) View in CoL designated by Peralta & Múlgura (2011: 393), in which the authors indicated: Brazil, s. loc., s.d., F. Sellow s.n. ex Herb. Impérial du Brésil 549 ( lectotype, designated here, P 650862!; isotype, SI!). Like typification of Cephalophora radiata Less. View in CoL above, HIB 549 should be a neotype because it is not part of the original material used by Sprengel, and therefore cannot be designated a lectotype.

Some neotypifications made when the original material was not found should be replaced by the isotypes discovered (ICN Art. 9.19, Turland et al. 2018), e.g., Aulomyrcia acrantha Berg (1857: 71) [= Myrcia glabra ( Berg 1857: 119) Legrand (1961: 298) ], for Sellow 2743 = Herbier Impérial du BRÉSIL N.o 1334 (P00549002, R [163625; 2 sheets]) ( Fig. 45 View FIGURE 45 ), Santo Antonio da Patrulha, April 1825, corresponds perfectly with the information of the protologue of Berg’s name (1857: 71), superseding the neotypification of Lima et al. (2018).

Duplicate numbering for different species from the same province, although not expected to occur, was found on some occasions. For S„o Paulo Province, e.g., 99 is repeated for two species, Olyra ciliatifolia Raddi (1823: 19 ; P01829051) and Duranta sp. (P02886122), and 39 from the same province, an undetermined specimen (P04457923) and Limnosipanea erythraeoides ( Chamisso 1834: 242) Schumann (1889: 253 ; P00729266). This, together with the unnumbered specimens at P and R, may indicate that Gaudichaud did not strictly follow the R numbering or mistakenly altered some numbers. Rio Grande Province 99 was not found at P but at R is Sesbania punicea (Cav.) Benth. These questions can only be addressed adequately after a more complete survey of the R collections.

The principal unresolved issue for HIB collections remains those from Mato Grosso. Although Silva Manso is most likely responsible for these collections (at least for some), so far, no R specimens have their original labels, such as those on specimens acquired by Martius and other herbaria. The few labels on P specimens ( Fig. 22 View FIGURE 22 ) with vernacular names and putative collection numbers, corroborate those Manso (1836) used in his publication on Brazilian purgative plants and in the hundreds of specimens from the Florula Matto-Grosso - Cujabensis , which were offered for sale (F̧rnrohr 1832). Manso indicated common names where known and available, including in the plant list sent to Martius, May 1833 ( Fig. 46 View FIGURE 46 ).

Another complication for Manso’s specimens is that they have been thus far only partially computerized, precluding a final assessment of which species he collected. Regardless of this, in Table 2 the Manso specimens located in different herbaria (ca. 37) were indicated for the related taxa of HIB. However, it is unlikely, although not impossible, that some HIB specimens are duplicates of those from Herbarium florae Brasiliensis (Martius 1837–1841) because they would have been collected by Manso on different dates.

For Acanthaceae, Nees von Esenbeck (1847a View in CoL ,b) recorded information about the specimens studied and collectors. Under Dipteracanthus geminiflorus var. hirsutior Nees von Esenbeck (1847a: 40) View in CoL stated “in prov. Matto Grosso: Patricio da Silva Manso”, whereas Nees von Esenbeck (1847b: 136), in which more detailed information was usually presented ( Moraes 2009a, 2012a), the Mato Grosso specimen is stated to be “herb. mus. paris.! n. 242”, which corresponds to Herbier Impérial du BRÉSIL N.o 51 (P03047385), with a duplicate in Nees’ private herbarium (GZU000249554) ( Fig. 47 View FIGURE 47 ). Under Stenandrium pohlii var. pusillum Nees von Esenbeck (1847a: 76) View in CoL stated “Var. β. ad fluvium Parana et in Matto Grosso: Riedel”, whereas Nees von Esenbeck (1847b: 283) stated “ Parana (Riedel! in h. acad. petrop. n. 49), Mato Grosso (h. Mus. paris.! n. 245). (v. in h. petrop. et paris.)”, a P specimen from the Herbier Impérial du BRÉSIL N.o 55 (P03584627), with a duplicate in Graz (GZU000250379) ( Fig. 47 View FIGURE 47 ). Thus, according to Nees von Esenbeck, the specimen of Dipteracanthus geminiflorus View in CoL was collected by Manso and that of Stenandrium pohlii View in CoL by Riedel. Another specimen, Herbier Impérial du BRÉSIL N.o 49 (P03047384) of Dipteracanthus macranthus Nees von Esenbeck (1847a: 37) View in CoL , which could be associated, Nees von Esenbeck (1847b: 118) indicated was “Cujaba (da Silva Manso! in herb. DC. n. 84)”. The specimen of Justicia comata ( Linnaeus 1759: 850) Lamarck (1785: 632) View in CoL , Herbier Impérial du BRÉSIL N.o 54 (P04052496) has a corresponding Manso collection at BR (BR0000005195824 – Silva Manso 82, Cuiabá, Apr 1833), which is certainly not a duplicate of the one at P because the collection date is indicative of material that Manso may have collected more than once for his later shipments.

The situation may be even more problematic for species that both Manso and Riedel are documented to have collected. For Gomphrena celosioides var. hygrophila ( Martius 1841: 66) Pedersen (1997: 228) View in CoL , there is Silva Manso 58 = Martii Herbar. Florae View in CoL Brasil. No. 581 (B†, F neg. 3243, BM000993142, BR0000006950859, BR0000006951184, G00236956, GH00037077, K000583083, LE, M0241718, NY00345556, P00622671, P00622672), which is material typical of G. hygrophila Mart. View in CoL collected in “humid. arenosis ripis Cuiaba Februar 1832 ”. There is also Riedel 823 (LE), “in humidiusculis tempore pluviali inundatis pr. Cuiabá”.

For Mesosetum ansatum (Trin.) Kuhlmann (1922: 42) View in CoL , typical Panicum ansatum Trinius (1830 View in CoL : t. 279) material is Riedel s.n. ( 769) (B 10 0366172, HAL0133168, K000643312, LE-TRIN-0570.01, MO-105107, P02609344, US 00148140, W0021652), “in siccis glareosis prope Cuiabá, Jan. 1827 ”, from where there is also Manso 46 (W0021651).

For Copaifera Linnaeus (1762: 557) View in CoL specimens collected by Manso and used by Martius in the Herbarium florae Brasiliensis , that of Copaifera nitida Martius ex Hayne (1827 View in CoL : sub tab. 17) is Silva Manso 97, Morro do Ernesto, Cuiabá, May 1830 = Martii Herbar. Florae View in CoL Brasil. No. 203 (BR0000008445568, G, HAL0120751, K000118773, M0215227, M0215228 [with label from Martii Herbar. Florae View in CoL Brasil. No 204], NY00004277, NY00004278, P00281345, P00281346, TUB009762, W18890341641), for which typical material, however, is Martius s.n., in sylvulis udiusculis Capıes dictis, Provinciae Minas Geraës, Martio 1818 (M0215226), which was used by Hayne (1827: tab. 17) for the description of the species, a synonym of C. langsdorffii Desfontaines (1821: 377) View in CoL (see Bentham 1870: 242). Although Dwyer (1954) determined the Herbier Impérial du BRÉSIL specimen N.o 286 (P00468486) as C. langsdorffii var. laxa ( Hayne 1827: tab. 18) Bentham (1870: 242), this fully agrees with the Silva Manso 97 duplicates and not Riedel s.n. ( 450), Rio Pardo (A, K000056100, LE), cited by Bentham (1870) for that variety and Dwyer (1951) as C. malmei Harms (1924: 713) View in CoL .

Under Copaifera martii Hayne (1827 View in CoL : tab. 15), for which typical material is Martius s.n., Provinciae Paraënsis, in sylvis ad fl. Amazonum (K000118765, L1986409, M0215214, M0215215, M0215216, M0215217, MEL252647, MEL252648, MEL252649, MEL2048149). Martius (1837–1841) attributed the collection of Silva Manso 95, Prope Cuiaba April. 1833 = Martii Herbar. Florae View in CoL Brasil. No. 204 (BR0000008445230, G-DC, K000118769, P00468420, TUB009763, W0066322, W0066339), as conspecific.However, as indicated by Bentham (1870),Martius’ identification was wrong because Silva Manso 95 is Copaifera elliptica Martius (1837: 127) View in CoL , based on Silva Manso 96, Prope Cuiaba April. 1829 = Martii Herbar. Florae View in CoL Brasil. No. 205 (A, BR0000009198081, K000118768, M0215231, F neg. 6206, P00468421, P00468422, TUB009764) ( Figs 48 View FIGURE 48 & 49 View FIGURE 49 ). Dwyer (1954) also cited and annotated the duplicates at P (P00468420, P00468421, P00468422) as C. elliptica View in CoL , indicating that they would be “ syntypes ” and, with some uncertainty, Riedel (?) 204, 205. In a footnote, Dwyer makes clear his lack of knowledge about the meaning of Martius’ Herbarium florae Brasiliensis and its collectors, as well as misinterpreting Bentham when he says that Bentham would have indicated Riedel as the collector of the type material: “Bentham cites Riedel as the collector of the type material, while specimens at Paris with Martius’ label and the numbers 204 and 205, bear no reference to Riedel”, for which Bentham cited “Habitat prope Cuiabá, prov. Mato Grosso: Riedel, Silva Manso, Mart. Herb. Fl. Bras. n. 204. 205.” This misunderstanding by Dwyer may have misled two other legume specialists, who annotated specimen M0215231 as “TYPE Riedel 205 from Matto Grosso /! G.P. Lewis 17.11.1983 ” and “Mart. Herb. Fl. Bras. 205 (col. Riedel?) Holotype of Copaifera elliptica Mart. View in CoL / H. C. Lima Oct. 2010 ”. The material of Riedel cited by Bentham, K000118768 (ex Herbarium Benthamianum) on which there is the annotation “... Cujaba Riedel in herb. Petrop cum fr. maiore,” thus referring to specimen(s) seen by Bentham in/from LE, probably Riedel 750, “in campis locis glareosis pr. Cuyaba, Jan. 1827 ” (NY01921760, NY01921761; mixed with labels and specimens by Philipp Salzmann from Bahia) ( Fig. 49 View FIGURE 49 ).

Ducke (1957) had already pointed out that Dwyer (1951) has serious errors because he studied collections in only six American herbaria, with no representation of any European (where most types are found) collections. Dwyer (1954) did not improve this picture much, adding an analysis of more collections from North American institutions and P. It was here that Dwyer cited the collections of HIB 231 (P00481386) and 287 (P00481387) (which were also noted by him in P; Fig. 48 View FIGURE 48 ), along with Pilger 282 (B 10 0089346), as being Copaifera malmei Harms View in CoL , indicating that the first two have minutely pubescent leaflets. Identification of the HIB specimens as being co-specific with the collection of Malme I 1344, in ‘cerrado’ et locis glareosis siccis et locis arenosis subhumidis, 1 Feb 1894 (A00053431, B†, F neg. 1515, V0076493F, V0076494F, V0076495F, G, R000002551, S-R-8685, S14-45416, S14-45419, US 00604033) ( Fig. 49 View FIGURE 49 ), which is the type material of Harms’ species, has raised serious doubts about the recognition of the species and circumscriptions adopted by Dwyer. For this reason, I have adopted here the identification of these specimens as C. elliptica Mart. The View in CoL typification of the last name ( Costa & Queiroz 2010), based on the thesis of the first author reproduced the same errors as above, which together with their comments did not bring order to the “accumulated chaos” in Copaifera View in CoL L. (Barneby 1996).

For Euploca filiformis (Lehm.) Melo & Semir (2009: 288) View in CoL , Manso is the collector of Martii Herbar. Florae View in CoL Brasil. No. 634 = Silva Manso 79, Prope Cuiaba Apr 1833 (BM, BR0000005198566, K, L2746206, L2746217, L2746218, M0187876, NY01067947, P03852631, US 01908582, W0058063, W18890284994; determined as Heliotropium filiformis Lehmann 1817: 1515 ), and of Martii Herbar. Florae View in CoL Brasil. No. 267 = Silva Manso 5, Prope Cuiaba in humidis humosis Sep 1833 (BR0000006967239, GH00097625, M0187872, P00610178, P00610179; determined as H. helophilum Martius 1838: 85 View in CoL ). In Fresenius (1857) and Johnston (1928), there was no indication of Riedel collecting this taxon in Mato Grosso and no specimens were located.

For Jacaranda rufa Silva Manso (1836: 40) View in CoL , no specimens from Manso have been located to date, causing Gentry (1992: 101) to make Pohl s.n. ( 766) the neotype (M0086433, F neg. 20476, M0086434, M0086435, W0057719, W0057720, W0057721), citing the label with “a Paracatu, S. Luzia, Paranahyba, S. Pedro”. For this species, there is Riedel 1177 (K000991472, K000991473, K000991474, K000991475, LE, P03576514), in siccis graminos, Serra da Chapada, Sept. 1827 View in CoL , which does not resemble the Herbier Impérial du BRÉSIL specimen N.o 88 (P03576537). HIB 88 could be original Silva Manso material because it is the only one known so far among his possible flowering collections that agrees with the description of the species. Another specimen with immature fruits, Herbier Impérial du BRÉSIL N.o s.n. (P03576538), would be further evidence of being a Manso collection because Riedel’s collection has no fruits.

There is a basic distinction between Silva Manso’s and Riedel’s collections: those of the former were collected in Mato Grosso during the 13 years he lived there, mainly in the surroundings of Cuiabá, probably in different periods, receiving sequential numbers, restarted for each hundred or shipment, whereas those of the latter are the result of his expedition there 1826–1828, visiting various places and regions, in which the collections are localised (in the different places) and received sequential numbering, not always chronologically. Thus, as already pointed out, the possible Manso collections in the Imperial Herbarium now at P would not necessarily belong to the same lot (of 100) that was traded by Lhotsky and could represent different phenology and/or morphology, possibly due to the collection of different individuals. If the specimens in the Imperial Herbarium were Riedel’s, these would inevitably have been made during the Langsdorff Expedition and would therefore be duplicates of those at LE, subsequently distributed to numerous herbaria. With this, one would expect that the morphology and/or phenology of the Imperial Herbarium specimens would be like those found in collections clearly documented to be Riedel’s. The limiting factor is that Riedel’s collections remain poorly known, except for those the nomenclatural types and in computerized databases.

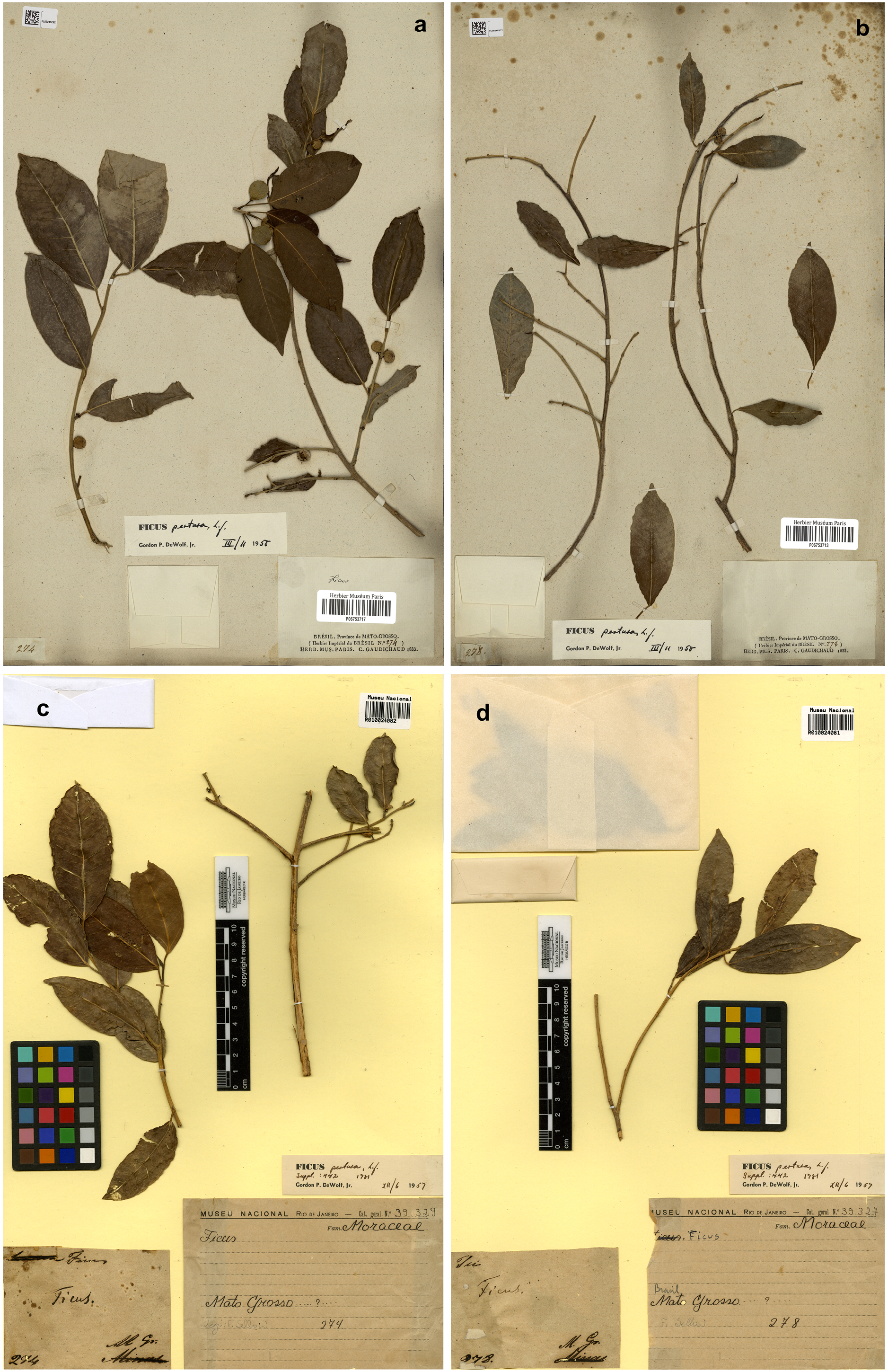

An additional complication comes from Imperial Herbarium labels with altered provenance, especially those originally annotated as Minas Gerais and later changed to Mato Grosso. This is the case for Aspidosperma tomentosum Mart. (R010014212) and two specimens of Ficus pertusa Linnaeus (1782:442) , R 39329 and R 39327, which correspond to those in Herbier Impérial du BRÉSIL N.o 274 & 278, respectively ( Fig. 50 View FIGURE 50 ). This causes some uncertainty over labels of some Imperial Herbarium specimens that originally may have been assigned incorrectly, in addition to later label changes and mixing of specimens.

The numerous hypotheses that have been raised here covering the identity of the taxa, synonyms, collectors and provenance of old collections with little information are obviously subject to future revelations. Ideally, as general collections are computerized, including historical material in addition to types, additional specimens by Sellow, Riedel and Silva Manso will be discovered and directly or indirectly connected to those in HIB. This will permit clarification of many questions raised here.

For cases where there is a particular interest, it is now possible with the most recent DNA methods to collect genetic/genomic data for centuries-old collections such as those of the Herbier Impérial du Brésil to resolve issues of identification and provenance ( Choi et al. 2015, Fertig 2016 a, Gutaker & Burbano 2017, Besnard et al. 2018, Bieker & Martin 2018, Carine et al. 2018, Wang 2018, Lang et al. 2019). Using standard plastid and nuclear markers, corroborative results on phylogenetic positioning and origin of old collections have also already been successful. Examples are Contreras-Ortiz et al. (2019), who established that Oncidium ornithorhynchum Kunth in Humboldt et al. (1816: 345, t. 80) is of Andean origin, despite the erroneous information of the protologue that the holotype was Mexican. Ames & Spooner (2008) analysed a plastid marker from historical herbarium specimens and demonstrated that cultivars from as early as the 16th century varieties of “English potatoes” ( Solanum tuberosum Linnaeus 1753: 185 ) originated in the Andes rather than the plains of Chile. However, introduction of Chilean potatoes occurred prior to 1811 and became predominant before the 1845 potato blight epidemic in Ireland, caused by Phytophthora infestans ( Montagne 1845: 313) de Bary (1876: 240) , contradicting a long-held belief among researchers that these were Andean varieties. Gutaker et al. (2019) analysed nuclear and plastid genomes from 29 historical herbarium specimens spanning 1660–1896 and 59 modern samples of South American varieties and European cultivars and found that the earliest European potatoes were tetraploid and originated in the Andes. Phylogenetic reconstruction of complete plastid genomes from herbarium samples allowed the assignment of specimens to plastid types, and analysis of the frequency of these at 100-year intervals indicated a decline in Andean varieties paralleled an increase in Chilean beginning in the late 18th Century. These and other examples in Choi et al. (2015) and Bieker & Martin (2018) make it clear that the methodological limitations for DNA sequencing of old samples have now largely been overcome, which opens up a range of possibilities for bio- and phylogeographic investigations of taxa that remain poorly known, involving collections here that were previously relegated to Brasilia or Montevideo.

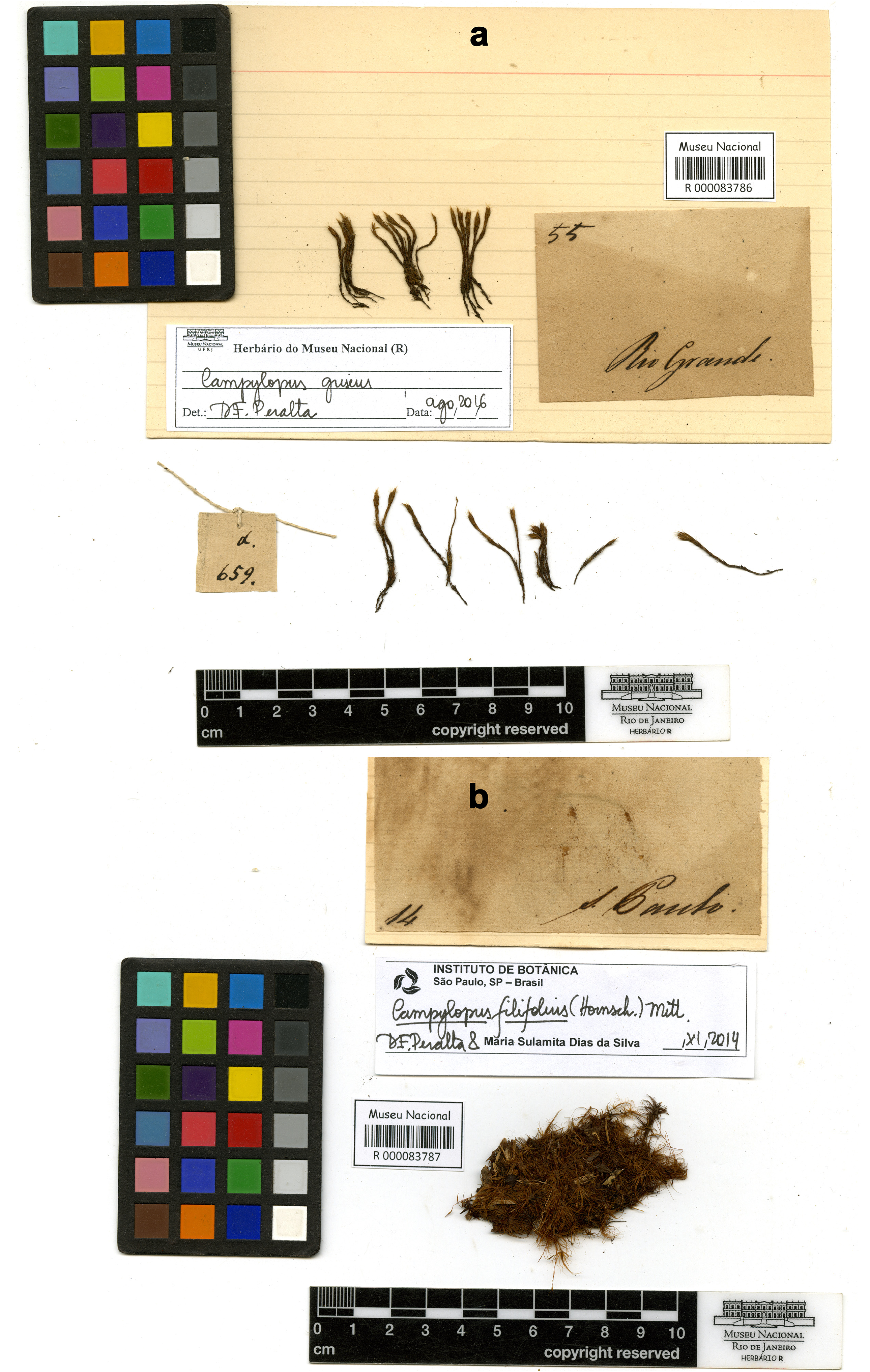

Finally, reiterating that research on the HIB cryptogam collections at both P and the National Museum still needs a great deal of attention. An example is Campylopus Bridel (1819: 71) of R material. Under Campylopus griseus ( Hornschuch 1840: 16) Jaeger (1872: 443) , there are Sellow specimens associated with the original Imperial Herbarium label Rio Grande 55 (R000083786) ( Fig. 51a View FIGURE 51 ). HIB material number 55 for Rio Grande Province was not located at P for neither phanerogams nor cryptogams. If also not found at PC, it could represent another case of specimens that were not removed by Gaudichaud. In addition to the specimens mentioned above, others were also found at R associated with Sellow’s original d 659 label, indicating that they were collected in Uruguay, Montevideo region. Since Sellow’s original B material of Thysanomitrion griseum Hornsch. was destroyed, the R specimens may be duplicates of those at KIEL ( lectotype designated by Frahm 1991: 109), BM000879662 or PC0692360.

Other cryptogam specimens from the Imperial Herbarium of Brazil now computerized in the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro provide additional evidence that Gaudichaud-Beaupré concentrated his efforts on organizing phanerogams, leaving in obscurity the PC cryptogam collections. Such is the case of the specimen of Campylopus filifolius ( Hornschuch 1840: 12) Mitten (1869: 76) labelled S. Paulo 14 (R000083787) ( Fig. 51b View FIGURE 51 ), which is duplicate for this province because there is also a P specimen, Spigelia beyrichiana Chamisso & Schlechtendal (1826: 203) , Herbier Impérial du BRÉSIL N.o 14 (P00507579). Here again, I wish to emphasize the need for scrutiny of the R collections to document specimens/species and their numbering.

Final considerations

Establishing an end point for this monograph is as ambiguous as its beginning. As originally conceived, this study was not considered on my part to be conclusive, analogous to the dream of many taxonomists aiming to produce a definitive work that will stand the test of time. In full agreement with Ng (1988), in practice, every taxonomic work, without exception, will be found lacking in one aspect or another. Here, the greatest effort has been given to the survey of specimens at the Herbier Impérial du Brésil, accompanied by information on their probable (with a degree of uncertainty) parallel collections elsewhere. Due to the large number of taxa, from diverse taxonomic groups involved, many keep the identifications in Sonnerat due to the impossibility of verification. However, these are suspect because they were made a long time ago (several specimens have no annotation labels) and have never been included in revisions of these families. Specialists in the different groups will need to determine their correct names.

As provocatively estimated by Goodwin et al. (2015), more than half of tropical plant specimens in the world’s major herbaria are likely incorrectly named or labelled with names now considered synonyms, and this undoubtedly includes those at P. However, critics of this study have pointed out that, among other things, synonyms are not equivalent to misidentification, especially since there may be several validly published names for a given taxon ( Fertig 2016b). Moreover, all taxonomists, professional or amateur, have surely misidentified a plant specimen at least once in their lifetime. Increased digitization and imaging of all herbaria would mitigate this problem by making specimens more easily accessible to specialists and thus reducing the number of errors. However, decreased job opportunities for taxonomists and fewer students working in this field may cause more identification errors in the future ( Fertig 2016b).

The historical importance and taxonomic relevance of the specimens in the Herbier Impérial du Brésil are undeniable, especially because they include Sellow’s duplicates that are the basis of taxonomic treatments of Flora brasiliensis and other related works of 19th Century botanists who studied his collections and which, unfortunately, were largely destroyed at B. Sellow specimens with their original labels at P and R are well represented in the Herbier Impérial du Brésil, removing them from the list of those without locality and date.As exemplified for several specimens, Sellow’s numbered labels make it possible to determine, even if only approximately, many of the locations/regions and periods/dates of his plant collections from Brazil and Uruguay. This is significant in a 19th Century context, during which naturalist collections were, as a rule, devoid of provenance. No less significant is the fact these were collected in areas of vegetation that no longer exist and possibly represent locally extinction populations. Thus, they may also represent morphological/genetic variants no longer found in nature ( Moraes 2009b). Another aspect to be considered within this context is that several previously unknown collection localities can now be further investigated for collection of new specimens. It should be considered that several of the taxa collected by Sellow have never been recollected in these localities. In this sense, rediscovery of such taxa is of significance also for their conservation ( Funk 2003, Bove & Philbrick 2014). Additionally, on this subject, Lughadha et al. (2018) emphasised that herbarium specimens provide verifiable, citable evidence of the occurrence of specific plants at specific points in space and time and are therefore essential resources for assessing extinction risk wherever diversity threats are greatest. Even with the existence of spatial, temporal, and taxonomic biases and uncertainties in herbarium data, specimens represent the best available evidence, and their use as the basis for extinction risk assessments is appropriate, necessary and urgent.

Another aspect to be considered, given the paucity of study focused on the HIB specimens, is the possibility that specimens may represent undescribed species despite being collected almost 200 years ago. From projections by Bebber et al. (2010), of the ca. 70,000 angiosperm species estimated yet to be described, more than half have already been collected and stored in herbaria, awaiting detection and description. Among the reasons given to explain why this phenomenon is more pronounced for older specimens ( Bebber et al. 2010), almost all are pertinent to the HIB specimens: i) herbaria are generally overloaded and specimens are either unprocessed or unavailable for study ( Holmes et al. 2016, Nelson & Ellis 2018); ii) lack of specialists in certain taxa, causing new species to go undetected, be misplaced or left as unidentified material at the end of each family; iii) incomplete specimens devoid of flowers or fruits; and iv) specimens that have been identified as new, annotated as such and perhaps even named on labels, but never published. As documented in Bebber et al. (2010), many new species only came to light after detailed comparison of the full range of species in a specific clade through monographic or revisionary papers. In some cases, the combination of more recent collections with the study of older, previously unrecognised collections that provided geographic and morphological evidence of a new species. That study suggested of necessity, discovery of new species in herbaria takes place in the context of through careful and continuous examination of all specimens of a given taxon. Thus, it is hoped that in future revisionary/monographic work, HIB specimens will finally be analysed in this framework.

According to Fertig (2016a), in the 19th to mid-20th Centuries, herbaria were at the forefront of research on the genealogical relationships based on morphology. This approach continues today ( Espinosa & Castro 2018), but it has been overshadowed by molecular data and modern methods of analysis. Closure of one in seven North American herbaria in the last twenty years has occurred through budget cuts and changes in academic priorities ( Dalton 2003, Gropp 2003, Deng 2015), which is even more perverse because it has occurred in the countries with the greatest wealth and strongest economies, e.g., Europe, East Asia and North America.

The use of the HIB specimens in studies with greater current appeal would also be expected to occur. Several species included here are invasive plants, making their history, geographic distribution and evolution of special research interest. The importance of studying herbarium specimens of invasive plants has been demonstrated, e.g., in understanding the spatial genetic structure of North American populations of Ambrosia artemisiifolia Linnaeus (1753: 988) ( Martin et al. 2014) and tracking the spread of Bromus tectorum Linnaeus (1753: 77) , a European invasive in the southwestern United States ( Pawlak et al. 2015). According to Muller (2015), herbaria are relevant for studies of the arrival and extent of invasive plants in a given area and can be used for the following purposes: (i) reconstruction of the history of the discovery of a new invasive species in particular locations; (ii) study of the speed of colonisation; (iii) characterization of the habitats in the zone of introduction and possible modifications of these environments; (iv) analysis of the comparison of genetic variability in their native ranges and in areas where they have become invasive; and (v) evaluation of their relative importance compared to natives in floristic compositions and temporal modification.

Studies related to anthropogenic climate change have also increasingly included historical specimens in their analyses. By examining herbarium collections of broad temporal ranges, it is possible to elucidate phenotypic and genotypic changes as adaptation to specific environmental changes occurs ( Holmes et al. 2016). Plant phenotypes are sensitive to temperature and atmospheric CO 2 concentrations, two aspects of recent anthropogenic environmental disturbances. For example, Woodward (1987) demonstrated a link between carbon dioxide concentrations and stomatal density of leaves of Acer pseudoplatanus Linnaeus (1753: 1054) , Carpinus betulus Linnaeus (1753: 998) , Fagus sylvatica Linnaeus (1753: 998) , Populus nigra Linnaeus (1753: 1034) , Quercus petraea ( Mattuschka 1777: 375) Lieblein (1784: 403) , Q. robur Linnaeus (1753: 996) , Rhamnus cathartica Linnaeus (1753: 193) and Tilia cordata Miller (1768 : n.1). The author observed an average 40% reduction in stomatal density of herbarium specimens (CGE) collected over a 200-year period (since 1750), during which the ice record indicated that atmospheric CO 2 increased by 60 µmol mol-1 (21%). These results were confirmed experimentally by growing seedlings of Acer pseudoplatanus , Quercus robur , Rhamnus cathartica and Rumex crispus Linnaeus (1753: 335) under pre-industrial CO 2 concentrations. The relationship between stomatal density and CO 2 concentration has also been examined by Beerling & Woodward (1996) by comparing modern and historical herbarium specimens.

For two Amazonian canopy species, Dicorynia guianensis Amshoff (1939: 28) and Humiria balsamifera Aublet (1775: 564 , t. 225), Bonal et al. (2011) evaluated the extent of recent environmental changes on morphological characters (stomatal density, stomatal surface area, leaf mass per unit area) and physiological characteristics (carbon and oxygen isotopic composition of leaves), from herbarium leaf samples from the Guiana Shield covering a 200-year period (1790–2004). Among the observed results, the authors found neither significant differences in leaf characteristics of either species with increasing CO 2 concentrations, nor a significant relationship between δ13C leaf or δ18O leaf and these characteristics, in particular stomatal density and surface area. However, they did observe a sharp decrease in δ13C leaf with increasing CO 2 concentrations, with no significant increase in Δ13C leaf. More examples of work involving responses to environmental change of plant phenotypes at the macroscopic level and in their phenology can be found in Holmes et al. (2016) and others involving a wide range of topics related to global change ( Lang et al. 2019).

The possibilities for studies and uses with/of HIB specimens are numerous, like those listed by Funk (2003) for herbarium collections in general. I highlight here a final example of the direct relationships between these specimens and Sellow’s known collections from detail provided by a review of the currently accepted names in Praxelis Cassini (1826: 261) . The nomenclatural type of Ooclinium grandiflorum Candolle (1836: 134) ≡ Praxelis grandiflora (DC.) Schultz-Bipontinus (1866: 254) is anonymous ( Sellow) s.n. = Herbier Impérial du BRÉSIL N.o 434 (P02476807), with duplicate at G-DC (G00464699) collected in the Province of S„o Paulo. The only known Sellow specimen of the species is Sellow 5494 (P02476853 – left specimen & P02476860), collected between Itapeva (Rio Pirituba) and Sorocaba in January–March 1829 ( Urban 1893), which according to number 5494 would be near (or already in the vicinity of) Sorocaba in February 1829. There is no recent collection of the species for this region, only collections from the 1940s and 50s for Itapetininga ( Abreu 2015).

| K |

Royal Botanic Gardens |

| LE |

Servico de Microbiologia e Imunologia |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Cortaderia selloana (Schult. & Schult.f.) Ascherson & Graebner (1900: 325)

| Moraes, Pedro Luís Rodrigues De 2023 |

Moorea argentea (Nees)

| Stapf, O. 1897: ) |

| Lemaire, C. 1855: ) |

Jacaranda rufa Silva Manso (1836: 40)

| Gentry, A. H. 1992: 101 |

| Manso, A. L. P. S. 1836: ) |