Eugenia alletiana Baider & V. Florens, 2013

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/phytotaxa.94.1.1 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03BF8793-FF8D-FFDB-54F4-E0CAB4A6FD82 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Eugenia alletiana Baider & V. Florens |

| status |

sp. nov. |

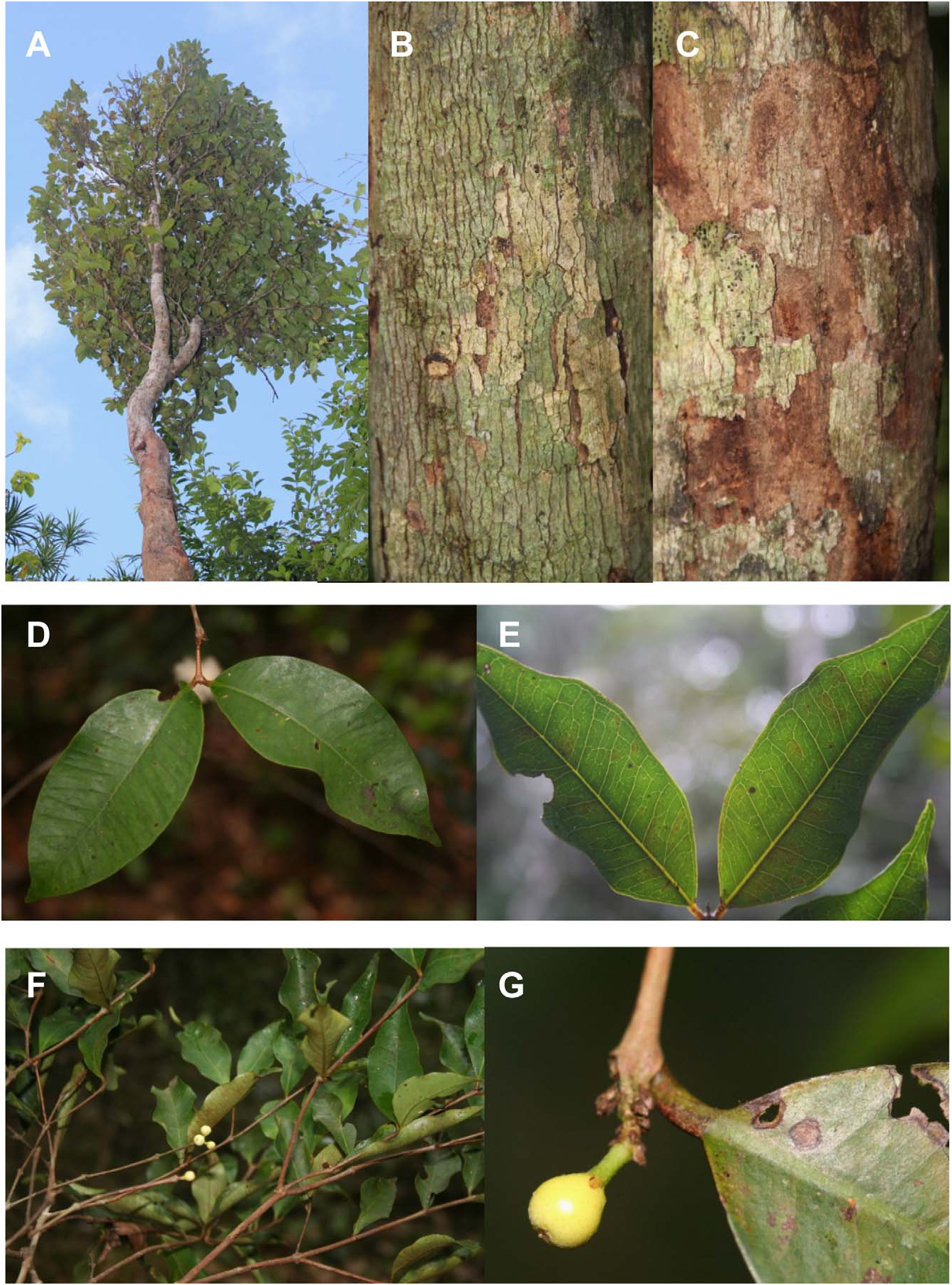

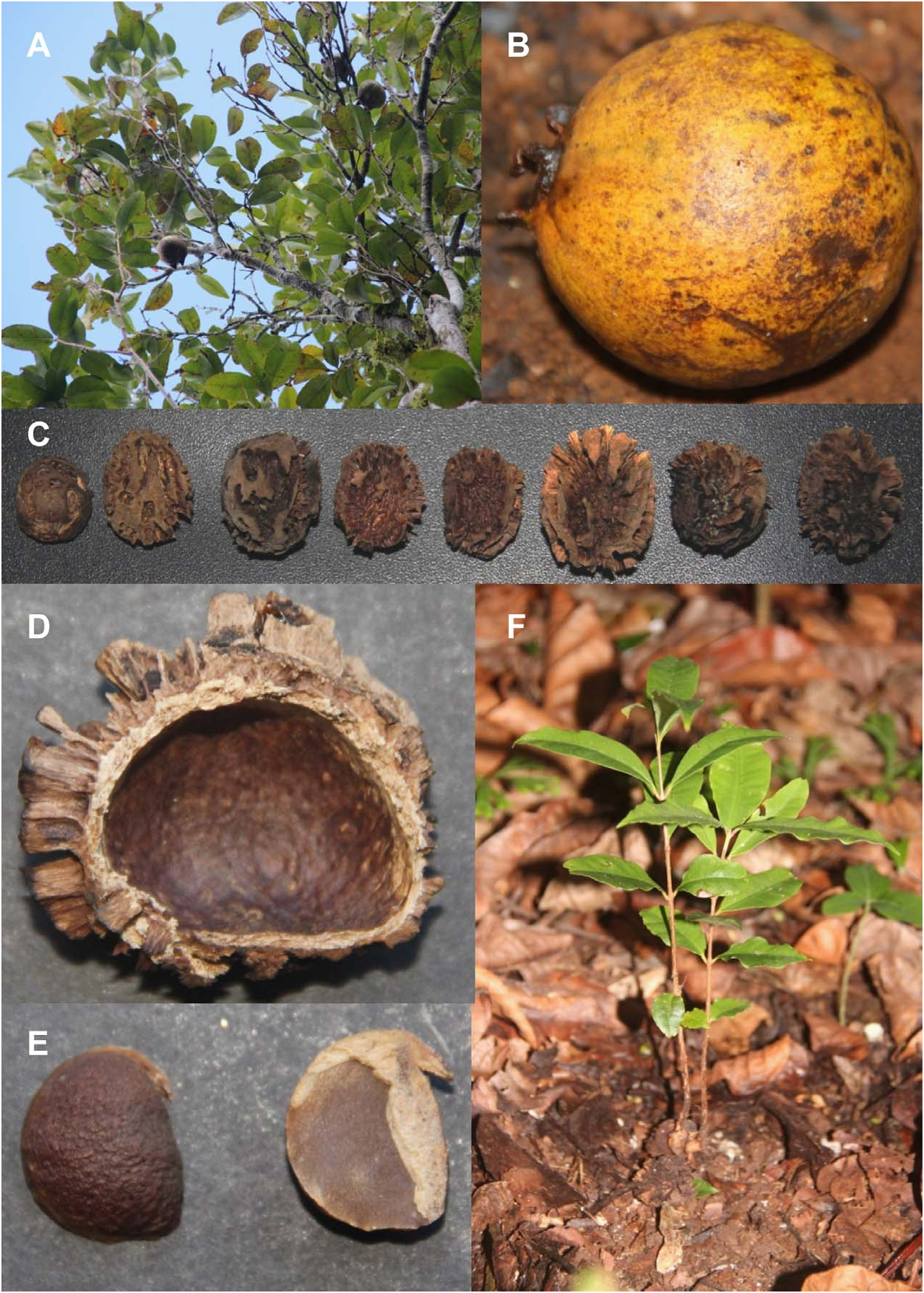

Eugenia alletiana Baider & V. Florens , sp. nov. ( Figs. 1 View FIGURE 1 , 2 View FIGURE 2 , 3 View FIGURE 3 )

Like other Eugenia of the Monimiastrum group, the stamens are distributed along the fused hypanthium tube which splits open during anthesis, but differs from all species of the group by the flower bud lacking an apical pore or calyptra, and by having at least twice more numerous stamens. Compared to the typical Mauritius Eugenia L. group, it is most similar to Eugenia elliptica Lam. and Eugenia bojeri Baker , but differs by having fewer lateral pairs of secondary veins, flowers that are solitary or in fascicles of 2–3 flowers, a shorter style and more ovules per locule (an unknown character for E. bojeri ).

Type :— MAURITIUS. Brise Fer, inside Conservation Management Area, 3 rd weeded permanent hectare plot (plant 7130), 20° 22’ 38.66’’ S, 57° 26’ 31.01’’ E, 590 m elev., 11 March 2011, fl., Baider CB 2440 & V. Florens (holotype MAU! [MAU 0010960], isotypes MAU! [MAU 0010961 & MAU 0010962], K!, P!) GoogleMaps .

Tree, small to medium sized 3.5–15 m tall, 3.5–35 cm diameter at breast height (mean dbh = 12 cm). Bark thinly fissured vertically, flaking irregularly, buff outside, chestnut to burnt sienna inside. Older branchlets terete, (1.7–) 2.3–3.3 (–4.2) mm diameter, bark smooth, glabrous, umber brown; current branchlets terete, (0.6–) 1–1.2 (–1.5) mm diameter, bark smooth, glabrous, chestnut to coffee brown, internodes (1.3–) 2.4–3.2 (–5.3) cm long. Leaves opposite, evenly distributed, chartaceous; surfaces discoloured, shiny forest green above, matt olive green below; venation brochidodromus, faint on both sides. Stipules 0.5–0.7 mm long, subulate, glabrous, sepia, caducous, rarely seen. Petiole (2–) 3–4.5 (–5.5) mm long × 0.6–1.6 mm diameter, rounded, glabrous, orange to reddish but becoming reddish brown when dry. Leaf blades (3.5–) 6–9 (–11.5) cm long × (2–) 3–4.5 (–5.6) cm wide, elliptic, base cuneate, tip acute, attenuate or acuminate, rarely rounded; margin wavy; glabrous on both sides; midrib canaliculate above, raised below; secondary vein pairs (9–) 10 (– 13); intramarginal veins not prominent, ca. (0.8–) 1.2–1.8 (–2.0) mm from margin at leaf midpoint. Pedicel 1– 2 mm long, slightly pilose, apple green when fresh, sepia when dry. Flowers terminal or rarely ramiflorous; fragrant when open. Bracteoles 3–5 mm long × 1–5 mm wide, subulate to subdeltate, slightly pilose to pilose, sepia. Flower buds 1–3. Hypanthium before anthesis obovoid to globose, 0.8–1 cm diameter; hairs scant, cream to light yellow, dotted dark yellow; apical pore lacking, apex slightly pilose, crowned by 4 deltate teeth. Hypanthium tube splitting into (3–) 4 (–5) segments assuming a reflexed position at anthesis, resembling calyx lobes; 6.2–6.8 (–9.2) mm long × 5.2–5.5 mm wide at base × 6.1–6.8 (–8.0) mm wide at largest part, ovate, apex truncate. Petals 4 (–5), rarely seen intact in open flowers, 3–3.5 mm long × 2.5 mm wide (measured from dissected dried bud), ovate with one lateral lobe, white, ciliate, hairs up to 0.25 mm long, inserted near the apex of split hypanthium tube lobes. Stamens numerous (> 500), distributed throughout the inside wall of the tomentose hypanthium tube lobes; filaments 3–7 mm long, shorter near the centre of the staminal disk, longer on edges of the split hypanthium tube lobes, white; anther sacs cylindrical, ca. 0.7 mm long, dorsifixed, white to beige, dehiscence longitudinal. Style 2–2.5 mm long, glabrous, white; stigma terete. Ovary bilocular, ca. 28–34 ovules per locule. Fruit oblate, (2.6–) 3–3.5 (–5.2) cm long, (2.7–) 3.3–3.6 (–5.7) × (2.6–) 3.3–3.8 (–5.2) cm wide; amber to saffron with tawny lines, dots and patches (depending on age and individual); crowned by persistent ruptured hypanthium tube lobes, 0.5–1.1 cm long × 0.6–1.1 cm wide at base. Endocarp 1–2 per fruit, oblate, woody, (1.6–) 1.8–2.3 (–3.2) cm long, (1.5–) 2.3– 2.8 (–3.7) × (1.4–) 1.6–1.8 (–2.9) cm wide, chestnut or russet brown; ornamented with irregular grooves forming variously shaped lamellae, 1–8.5 mm deep (on the same endocarp). Seed ellipsoid, 1.9–2.0 cm long, 1.4–1.6 × 1.4–1.6 cm wide, testa bullate, sepia to russet brown; cotyledons large, thick, partly connate, with chesnut to russet cotyledon surface.

Etymology: —The epithet is in recognition of the considerable botanical contribution and dedication to the conservation of the local flora of Mr. Mario Allet, Park Ranger of the National Parks and Conservation Services ( Mauritius).

Comparison with other Mauritian species: —Compared to other endemic Mauritian Eugenia ( Scott 1990) , E. alletiana is one of the three species typically having ≥ 10 lateral vein pairs ( Fig 1D–E View FIGURE 1 ). But E. alletiana has fewer than 15 lateral vein pairs unlike both E. bojeri and E. elliptica (Lam. 1789: 206) . Eugenia alletiana leaves are much smaller than the smallest leaves of E. bojeri . While the largest leaves of E. alletiana overlap in size with those of E. elliptica , the smallest ones are substantially smaller. It is worth noting that the leaf shape and wavy margin of E. alletiana more closely resembles those of the Mauritian Syzygium (e.g., S. guehoi ) than other Mauritian species of Eugenia .

The flowers of E. alletiana are single or in a fascicle with a maximum of three flowers ( Fig. 1F–G View FIGURE 1 ), whereas E. bojeri and E. elliptica have 5–10–flowered fascicles. E. alletiana is not cauliflorous as E. bojeri sometimes is. Flowering in Eugenia bojeri (November to December) and E. elliptica (October to December, extending sometimes to February) is earlier than in E. alletiana (March to April, sometimes starting in February). In addition, E. elliptica has fewer ovules per locule compared to E. alletiana (> 25). The fruit of E. alletiana is smaller than that of E. elliptica , with the latter species fruiting when E. alletiana is in flower. Fruits of E. bojeri are unknown (only an old empty endocarp has ever been collected recently by the authors), suggesting that it would tend to be smaller than the fruits of E. alletiana . The outer surface of the endocarp in these three species is irregularly indentated or lamellated; however the lamellation is more pronounced in E. alletiana .

Although Eugenia alletiana has a flower structure more similar to the Eugenia of the Monimiastrum group ( Scott 1990), the species possesses few other characters in common. Eugenia of the Monimiastrum group ( Scott 1990) have either solitary flower ( Eugenia petrinensis N. Snow , E. pyxidata (Guého & Scott) N. Snow and E. psidioidea (Guého & Scott) N. Snow (2008: 348)) or 2–5 ( E. kanakana N. Snow (2008: 348)) or 3–6–flowered fascicles ( E. longuensis ), unlike E. alletiana which has flowers that can be both solitary or in fascicles of 2–3. In contrast with E. alletiana , all former Monimiastrum species except E. longuensis have coriaceous leaves and in all (except E. longuensis where this character is unknown), the youngest pair of new leaves at each branch apex are, during development, borne with their adaxial surfaces adhering to each other (a field character). Eugenia longuensis differs from E. alletiana by having flower buds with dense indumentum and an apical pore, smaller fruits (ca. 2 cm diameter) and thicker and whitish branchlets. The fruit and seed are larger in E. alletiana than in any other Eugenia of the Monimiastrum group except possibly in E. pyxidata (Guého & Scott) N. Snow (2008: 348) where the fruit and seed are not known. Eugenia longuensis has also only been collected from dry habitats.

It is also worthwhile to note that no other species of Mauritian Eugenia (including those of the Monimiastrum group) has so thin terminal branchlets ( Fig. 1F View FIGURE 1 ).

Additional specimens examined (paratypes): — MAURITIUS. Bassin Blanc , near foot path by lake’s edge, ca. 20° 27’ 15.20’’ S, 57° 28’ 37.44’’E, 460 m elev., 26 November 2006, V. Florens & Baider [MAU 0010958]; Brise Fer, non-weeded permanent hectare plot (plant 4265), 20° 22’ 36’’ S, 57° 26’ 22’’ E, ca. 560 m elev., 03 Feb 2008, Baider CB 2047 & V. Florens [MAU 0010959]; Brise Fer, non-weeded permanent hectare plot (plant 4401), 20° 22’ 35’’ S, 57° 26’ 22’’ E, ca. 560 m elev., 03 Feb 2008, Baider CB 2048 & V. Florens [MAU 0010963 & MAU 0010964]; Brise Fer, non-weeded permanent hectare plot (plant 4588), 20° 22’ 35’’ S, 57° 26’ 21’’ E, ca. 560 m elev., 03 Feb 2008, Baider CB 2049 & V. Florens [MAU 0010955]; Brise Fer, non-weeded permanent hectare plot (plant 4627), 20° 22’ 35’’ S, 57° 26’ 21’’ E, ca. 560 m elev., 03 Feb 2008, Baider CB 2050 & V. Florens [MAU 0010956 & MAU 0010957]; Brise Fer, non-weeded permanent hectare plot (plant 5109), 20° 22’ 35’’ S, 57° 26’ 21’’ E, ca. 560 m elev., 03 Feb 2008, Baider CB 2051 & V. Florens [MAU 0010970]; Brise Fer, inside Conservation Management Area , 3 rd weeded permanent hectare plot (plant 7130), 20° 22’ 38.66’’ S, 57° 26’ 31.01’’ E, 590 m elev., 03 Feb 2008, fl. bud, Baider CB 2058 & V. Florens [MAU 0010971, MAU 0010972 & MAU 0010973]; Brise Fer, inside Conservation Management Area , 3 rd weeded permanent hectare plot (plant 7156), 20° 22’ 38.49’’ S, 57° 26’ 31.01’’ E, 590 m elev., 01 March 2008, fl., Baider CB 2056 & V. Florens [MAU 0010966]; Brise Fer, inside Conservation Management Area, 3 rd weeded permanent hectare plot (plant 7130), 20° 22’ 38.66’’ S, 57° 26’ 31.01’’ E, 590 m elev., 01 March 2008, fl., Baider CB 2057 & V. Florens [MAU 0010967, MAU 0010968 & MAU 0010969]; Le Pouce, 20° 11’ 57.50’’ S, 57° 31’ 51.06’’ E, 674 m elev., 31 August 2011, fr., Baider CB 2498 & V. Florens [MAU 0010952 & MAU 0010953]; Le Pouce, 20° 11’ 57.24’’ S, 57° 31’ 50.00’’ E, 688 m elev., 31 August 2011, Baider CB 2497 & V. Florens [MAU 0010954]; Brise Fer, inside Conservation Management Area in the ‘Old Plot’, ca. 20° 22’ 42.36’’ S, 57° 26’ 26.03’’ E, 585 m elev., 10 February 2012, fr. (spirit only), Baider CB 2572 & V. Florens [MAU 0010965] GoogleMaps .

Taxonomical Notes: — Eugenia alletiana appears to be one of the very few members of Myrtaceae to possess a remarkable androecium and mode of anthesis. The tube of the hypanthium is expanded above the ovary and reduces in width towards the apex, hence its globular shape ( Fig. 1G View FIGURE 1 ). The apex of the hypanthium tube is fused such that it completely encloses the stamens, style and the reduced petals ( Fig. 1G View FIGURE 1 , Fig 2E–F View FIGURE 2 ) before anthesis; assuming the function of a protective cap ( Fig. 2A View FIGURE 2 ). In this case, the calyx seems to have become redundant. The only totally fused hypanthium tube of a Myrtaceae in the Mascarenes, is that of Eugenia pyxidata (Guého & Scott) N. Snow (2008: 348) , but this species has a calyptrate flower bud with an acute or apiculated apex ( Scott 1980).

E. alletiana also has a greatly increased number of stamens (> 500) ( Fig. 2D View FIGURE 2 ), even more than the Eugenia of the Monimiastrum group, which tend, in turn to have more stamens (200–300) than the other Mauritian Eugenia . To accommodate such large numbers of stamens, the staminiferous tissue of E. alletiana extends down the inside of the hypanthium, unlike the standard condition in Myrtaceae , in which the stamens are inserted on a disc at the hypanthium apex ( Wilson 2011). Therefore, for the stamens to be presented to pollinators, at anthesis, the hypanthium tube ruptures into usually four segments (rarely three or five), which then recurve ( Fig. 2C, 2E–F View FIGURE 2 ). This androecial condition, apart from its presence in Mauritius itself in other Eugenia , in form of the generic concept of Monimiastrum ( Scott 1980) , can also be seen in New Caledonia in the generic concept of Stereocaryum s.l. Burret (1941: 546). Stereocaryum has been suggested, like Monimiastrum , to have evolved from an ancestral Eugenia ( Van der Merwe et al. 2005) and may be included under that genus (N. Snow, pers.comm.). Finally, the peculiar androecial condition seen in E. alletiana is also present in Eugenia sect. Fissicalyx Henderson (1947: 333 ; Craven & Biffin, 2010) from the Peninsular Malaysia and New Guinea.

Although flowers of Eugenia alletiana are most similar to Eugenia of the Monimiastrum group and of Stereocaryum s.l., its endocarp morphology resembles that of two species of Mauritian Eugenia ( E. elliptica and E. bojeri ). The outer surface of the endocarp is irregularly grooved creating lamellae that vary in thickness and lengths between endocarps from the same tree or, even between parts of the same endocarp. This gives a surface covered with irregular sharp woody processes at one extreme (when grooves are numerous), and a relatively smooth surface interrupted by occasional grooves at the other extreme ( Fig. 3C–D View FIGURE 3 ).

Phenology: —The smallest dbh of a mature tree is around 3.5 cm, but flowering at this size seems sporadic, unlike in larger plants (dbh> 10 cm). Flower buds can be observed from mid December to March. Flowering: February (rarer); March–April. Fruiting: January to February. At end of January 2012, ripe fruits were for the first time seen in Brise Fer, after some individuals were monitored for nearly five years.

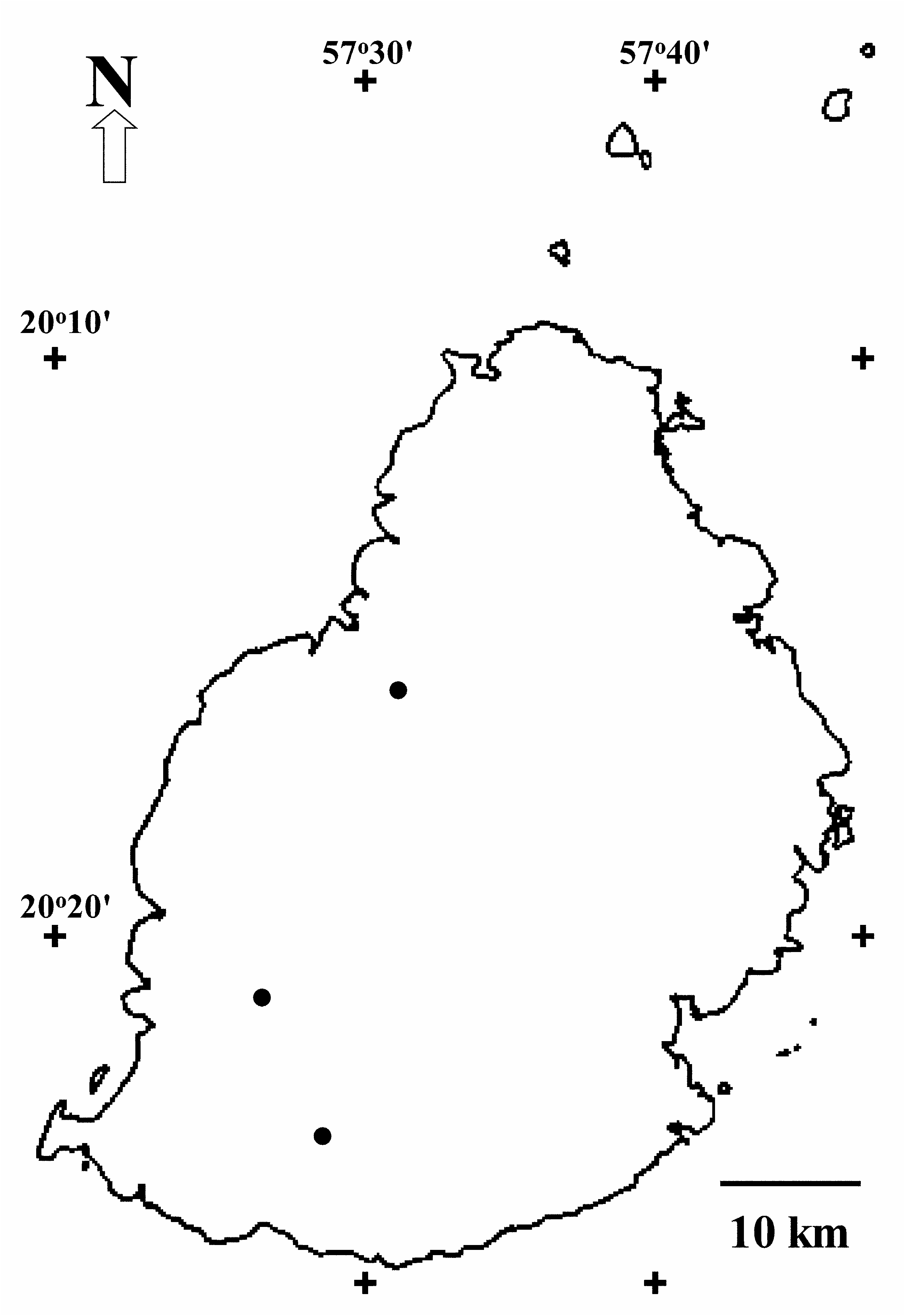

Distribution and habitat: —Endemic to Mauritius; known only from Le Pouce Mountain, Bassin Blanc, and Brise Fer ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ).

Eugenia alletiana grows between 20 0 11’–20 0 27’ S latitude and 57 0 26’–57 0 31’ E longitude, at 460–750 m elev., on ferralitic soil or lithosols formed from volcanic rocks ( Willaime 1984). The three sites are in the humid or super-humid zones of Mauritius (Parish & Feillafé 1965), with annual rainfall varying from 1,400 mm (Le Pouce) to 3,000 mm (Bassin Blanc) ( Willaime 1984) and mean annual temperatures of about 20 º C ( Halais & Davy 1969). The species occurs in upland forest sensu Vaughan & Wiehe (1937), with native canopy ranging from 7 m (in the wind battered slopes of Le Pouce) to 15 m high, with emergent trees up to 18 m tall (in Brise Fer). Eugenia alletiana typically grows along emergent trees from the family Sapotaceae ( Sideroxylon L. 1753: 192–193, and Labourdonnaisia Bojer 1841: 295 ), and with Warneckea trinervis (DC.) Jacq. –Fél. (1978: 235; Melastomataceae ), Securinega durissima J. F. Gmelin (1791: 1008; Phyllantaceae ), Diospyros tessellaria ( Poiret 1804: 430; Ebenaceae ), Erythrospermum monticolum Thouars (1806: 67 ; Achariaceae ) and Syzygium glomeratum (Lam.) DC. (1828: 259; Myrtaceae ).

These native forests are seriously invaded by alien plants which comprise mainly Psidium cattleianum Sabine (1821: 317) (Myrtaceae) and to a lesser extent Ligustrum robustum (Robx.) Blume subsp. walkeri (Decne.) P. S. Green (1985: 130 ; Oleaceae ). Known sympatric species of Eugenia are E. pollicina (Guého & Scott in Scott 1980: 480), E. elliptica , E. kanakana , E. psidioidea and E. pyxidata .

Ecology and Conservation status: — Eugenia alletiana grows in wet native vegetation on an island that already has a high proportion of its plant species threatened with extinction due to a suite of anthropogenic impacts ( Baider et al. 2010, Caujapé-Castells et al. 2010). When several plants are known to co-occur, there is a clear tendency for a relatively clumped distribution, suggesting seed dissemination may be weak. The large majority of plants are found in relatively flat areas with very few exceptions on sloped mountain flanks.

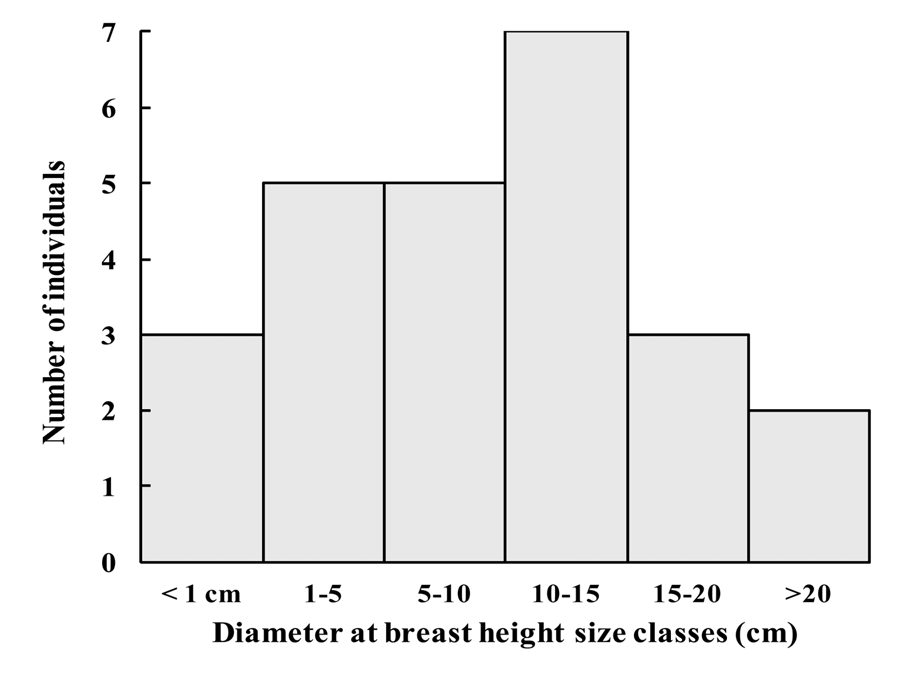

Apart from some seedlings, 22 adult and 4 juvenile individuals are known: 18 in Brise Fer, seven on Le Pouce and one in Bassin Blanc ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ). The area of Bassin Blanc has not been surveyed in detail. Most plants have some degree of legal protection, being found in the Black River Gorges National Park ( Brise Fer ), or in both Nature and Mountain Reserves (Le Pouce). Fortunately, most known adults (62%, N = 13) found in the National Park are within a Conservation Management Area (CMA), where invasive alien plants are controlled. Consequently, 38% of the known world population of the species grow within native forests that are much invaded by invasive alien plants including all known plants of two of the three sites .

Studies in Mauritius have shown that native plants growing alongside invasive alien plants face serious risks. Their growth rate is reduced ( Florens 2008), the number of flowers and fruits produced can be greatly reduced ( Baider & Florens 2006, Monty et al. 2013), such that natural regeneration can be very low or even halted depending on species ( Baider & Florens 2011). Mortality of established native trees is also higher in weed infested areas compared to where the weeds are controlled ( Florens 2008). Even native butterfly species richness and abundance are greatly reduced in the presence of alien weeds compared to forests that have been rid of alien plants ( Florens et al. 2010). Since butterflies represent adequate indicators of change for many other terrestrial insect groups ( Thomas 2005), it is likely that invasive alien weeds negatively impact pollination of native plants through a reduction of abundance and/or diversity of insect pollinators (Kaiser- Bundury et al. 2010). Furthermore, the large fruits of E. alletiana have been observed to be picked and chewed by invasive alien monkeys ( Macaca fascicularis ) before they ripen, thus destroying the developing seeds. Similar attacks on large fruited species in Mauritius are known to seriously compromise regeneration ( Baider & Florens 2006). Seeds were also observed to be predated by rats ( Rattus sp. ), of which two introduced species occur in Mauritius. The impacts from alien species collectively reduce regeneration of the species. Indeed, quantitative seedling surveys using sampling plots have failed to reveal any seedlings of E. alletiana in their stronghold locality at Brise Fer forest ( Baider & Florens 2011). The only seedlings (N = 25) found were inside the weed–free area, virtually all under one mother–tree in a patch of the forest weeded for a longer time (26 years compared to 16 years for most of the weeded area of Brise Fer). All seedlings appear to be of the same cohort (between 9–32 cm tall). It is clear that regeneration has been poor for some time, as there are far less plants of smaller diameter ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ) than expected in a normally regenerating population.

The species is known from <50 adults, distributed in three localities in a highly fragmented landscape (area of occupancy <1 km 2; area of occurrence of ca. 73.6 km 2, calculated using Google Earth and GE Path v 1.4.4a as per the Sampled Red List Index for Plants (2010)). It grows in habitats sustaining worsening degradation by invasive alien plants (except for part of one population) and its fruits and seeds are destroyed by invasive alien mammals. Consequently, Eugenia alletiana should be considered as Critically Endangered (CR B1, B2a, b(iii), D) according to the IUCN Red List Criteria ( IUCN 2001).

Active conservation management is urgent for ensuring the long–term survival of the species. The highest priority is the removal of invasive alien weeds from the E. alletiana habitat or, at least, from the immediate surroundings of known trees, to reduce mortality risks and to help enhance plant fitness and hence seed production. The next priority is to either protect the plants from monkey attacks (e.g., with monkey-proof enclosures) or control the monkey population to a level that would allow in–situ fruit ripening. The localised control of rats seems also advisable since fewer seeds appear to have been predated where rat control has been done (Brise Fer). The native seed disseminator of the species is not known, and most seedlings were found in the canopy shadow of mother–trees. It is likely that giant tortoises or dodos would have consumed the fallen fruits, but with these likely disseminators being extinct, seed dissemination may become the next conservation challenge once the above priority conservation measures are addressed. For example, eventual introduction of analogue tortoise species could be envisaged ( Griffiths et al. 2010). Given the large size of the fruit of this species, the only probable extant native disseminator is the Endangered Greater Mascarene Flying Fox ( Pteropus niger ), an animal that is illegally persecuted on the island mainly by fruit growers and whose legal protection is in risk of being lifted (Florens 2012). Indeed, one ripe fruit had been observed that had bat`s teeth marks in its partially eaten pulp, suggesting that the fruit bat may be the only current seed disseminator of the species.

| V |

Royal British Columbia Museum - Herbarium |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |