Cassida flaveola Thunberg, 1794

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.182782 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6228617 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03BD1870-C01B-9E54-20D7-2EC07519ABCA |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Cassida flaveola Thunberg, 1794 |

| status |

|

Cassida flaveola Thunberg, 1794 View in CoL

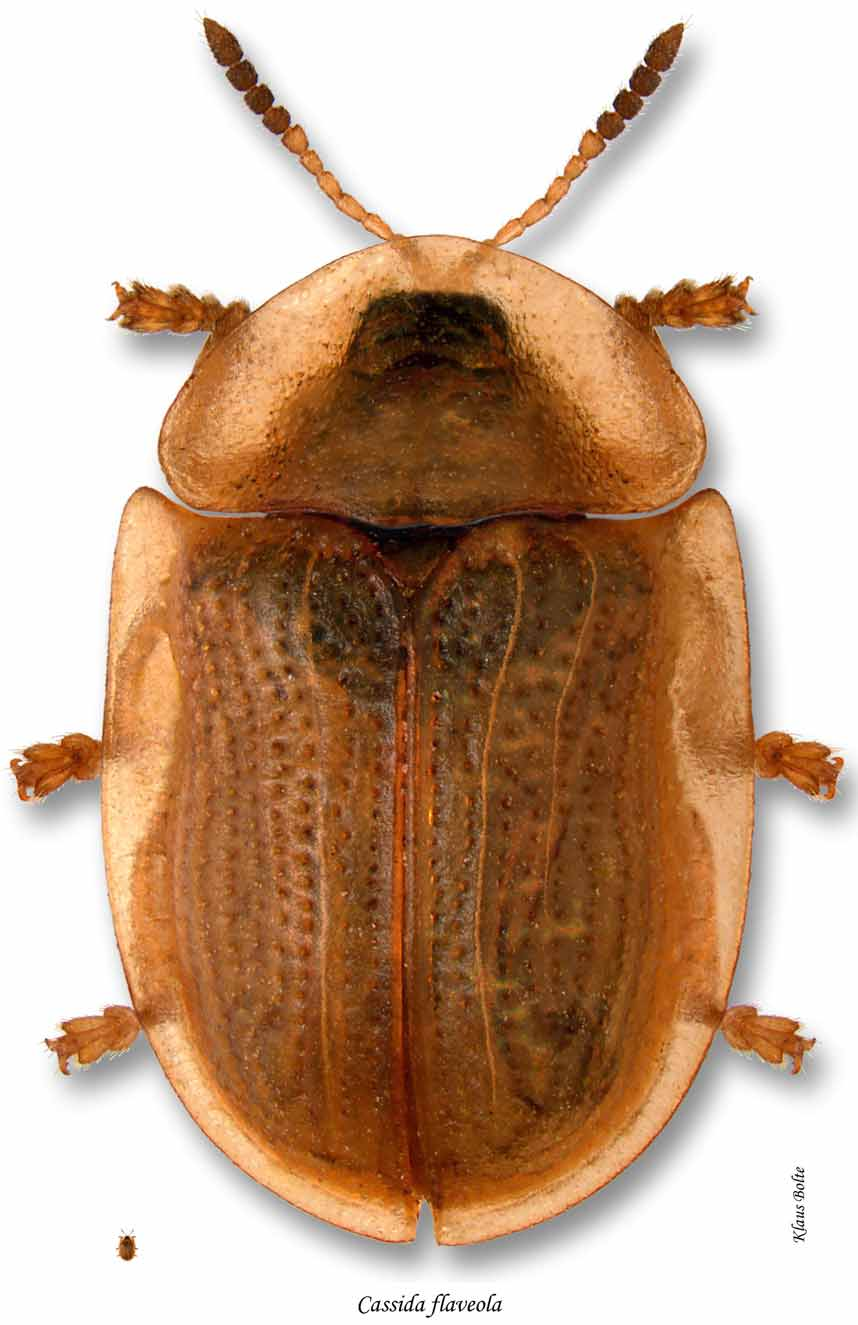

Identification. Keys for the identification of adult C. flaveola are found in Barber (1916), Wilcox (1954), Chagnon & Robert (1962), Riley (1986a, 1986b), Downie & Arnett (1996), and Riley et al. (2002). Adults of C. flaveola are distinctly smaller (4-5 mm) than those of C. rubiginosa (6-8 mm), their elytral punctures are arranged in regular rows whereas they are confused in C. rubiginosa ( Fig. 1), and the pronotum and elytra are yellowish brown with translucent margins ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 ).

History and distribution. Early records of C. flaveola reported by Barber (1916) were from Beaver Dam, Wisconsin (1896 and 1911), Rigaud, Québec (1902), and Duluth and Mora, Minnesota (1907). Barber (1916) also indicated that a specimen reported as C. nobilis L. by Mannerheim (1853) from Sitka, Alaska may have been C. flaveola . However, this specimen is no longer in the Zoological Institute collection in St. Petersburg, Russia and may now be lost ( Riley 1986b). Cassida flaveola has subsequently been broadly reported in North America from the Yukon, Northwest Territories, and British Columbia, east across Canada to Québec, and in the United States from New Hampshire south to Maryland and West Virginia, and west to Minnesota, North Dakota, and Montana ( LeSage 1991; Riley et al. 2003). In the Old World , its distribution is similar to C. rubiginosa except that in Europe it has not been recorded from Portugal, Sicily, Croatia, Greece, and southern Russia ( Audisio 2005a).

Biology. Little is known of the biology of Cassida flaveola in North America. Open habitats are apparently preferred. Most Nova Scotia specimens were collected in pastures, one was found on seashore on coastal dunes, and one specimen preserved in the CNC was collected in an alvar in Almonte (Ontario).

Kosior (1975) investigated the developmental biology of the species in Ojcow National Park in Poland. The following account of the biology of C. flaveola is based largely on his investigations. One to two eggs (average 1.6) are laid on host plants. Eggs are laid on the underside of leaves and are covered with a yellowish-brown protective layer ( Kleine 1917b). Eggs took an average of 18 days to hatch and then the larvae developed through four instars averaging 6.7, 6.5, 7.5, and 7.0 days at each stage. The larvae then pass through a pre-pupal stage (3.2 days) and then pupate, the adults emerging after 9.0 days. Thus, complete development averaged 57.9 days in 1971. In 1970 when ambient temperatures averaged slightly warmer (14.0 ºC versus 11.8ºC) the development time averaged 53.3 days. This was the shortest development time of the four species of Cassida that were investigated at the same site. Larvae were present in the field for a period of 2.0-2.5 months. In contrast to many other species of Cassida , the larvae of C. flaveola do not form a fecal shield of clumps of excrement and exuviae of larval skins. The larvae leave these on the surfaces of leaves on which they are feeding. The larvae feed by perforating the leaves, which can sometimes turn brown and die, however, feeding does not usually kill the plants ( Kleine 1917b). Pupation takes place on neighbouring grasses or herbaceous plants. Preceding pupation, the larvae (in the pre-pupal stage) sit motionless on the underside of leaves attached to the substratum with a brown sticky substance secreted from the fifth, sixth, and seventh segments. Pupation then takes place very quickly, in 2-3 minutes.

Adult emergence is also quite rapid, taking only 5 minutes in field conditions. In general, females are larger than males. The adult coloration is light creamy on both dorsal and ventral surfaces. The young imagos sit motionless for approximately 6 hours and begin to feed after 6-9 hours. After 24 hours the colouration has changed to light brown. Adults feed either on the edges of leaves, or else directly on the surface of leaves, however, the opposite side of the epidermis remains untouched ( Kleine 1917b). Adult beetles were present in the field for 1.0 to 2.5 months after which dipause commenced (triggered by temperature, humidity, and day length) and the adults moved from the fields where they fed, to neighbouring forests where they burrowed into forest litter to a depth of 5-8 cm to hibernate for the winter. In Poland, adults emerged the following year between 9 May and 7 June. After mating, first-year females lay an average of 242 eggs (range 179-299) in small batches (average 1.6) on suitable vegetation. Second year females also lay eggs, but in much reduced numbers (an average of 38; range 27-48; 1.4 eggs/batch). Females live up to 24 months (average 13.9), whereas males live a maximum of 22 months (average 12.6). Air temperature, wind, rain, and exposure to sunlight all influence the populations and development of all species of Cassidinae , including those of C. flaveola ( Kosior 1975) .

In Poland, C. flaveola is an abundant species in meadows throughout the country. Adults are found from May to October ( Wasowska 2004). In southern Poland, Wasowska (2004) found it to be the sixth most abundant chrysomelid in both mown and un-mown meadows, with a very stable population structure from year to year.

Parasitism. Kosior (1975) found that different developmental stages of C. flaveola were parasitized by Agamomermis sp. (Nematoda: Mermithidae ), Foersterella flavipes (Förster) and Foersterella erdoesi Boucek ( Hymenoptera : Tetracampidae ), Entedon cassidarum Ratzeburg ( Hymenoptera : Eulophidae ), Ferrierella sp. ( Hymenoptera : Mymaridae ), and Dufouria nitida von Röder ( Diptera : Tachinidae ). Parasitic Hymenoptera generally laid one egg inside each C. flaveola egg, although instances of as many as four eggs were observed. The proportion of parasitized eggs ranged from 34.5% in 1970 to 31% in 1971. The most important hymenopteran parasite was Ferrierella sp. which accounted for 97% of the parasitism in eggs, and Entedon cassidarum which accounted for 100% of parasitism in larvae and pupae. The principal parasite affecting adult C. flaveola was Dufouria nitida , which parasitized and caused a mortality of 20% of adults.

Predation. Kosior (1975) found that different developmental stages of C. flaveola were preyed upon by Anthocoris nemorum Linnaeus (Heteroptera: Anthocoridae ), Nabis apterus Fabricius and Nabis limbatus Dahlborn (Heteroptera: Nabidae ), Picromerus bidens Linnaeus (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae ), Cantharidae species larvae ( Coleoptera ), Linyphilidae species (Araneida), Lycosidae species (Araneida), Phalagium sp. ( Opiliones : Phalangiide), Poecilochirus necrophori Vitzthum ( Acari : Parasitidae ), Pergamasus septentrionalis (Oudemans) ( Acari : Parasitidae ), Microtrombidium sp. ( Acari : Trombidiidae ), Leptus sp. ( Acari : Erythraeidae ), Erythraeus sp. ( Acari : Erythraeidae ), and Anystis sp. ( Acari : Anystidae ). The rate of predation found by Kosior (1975) in 1970 in the field was 6.7%.

Host plants. Cassida flaveola is a polyphagous species and has been associated with a number of plants in the Caryophyllaceae including Arenaria peploides L., Cerastium vulgatum L., Honckenya peploides (L.), Malachium aquaticum (L.) Fr., Minuartia sp., Myosoton aquaticim (L.) Moench, Sagina sp., Silene latifolia Poiret , S. vulgaris , Spergula arvensis L., Stellaria graminea L., S. holostea L., S. media (L.) Vill., S. nemorum L., and S. uliginosa Murr. ( Kosior 1975; Clark et al. 2004). Kosior (1975) reported that the preferred hosts were species in the genera Stellaria , Spergula , and Honckenya , and the most preferred species is S. graminea . Of these host plant genera all except Malachium , Minuartia , and Myosoton are found in the Maritime Provinces and many species are widely distributed in the region ( Erskine 1960; Hinds 1986; Roland 1998). In Bible Hill (Nova Scotia), the species was found feeding on Stellaria graminea (grass-leaved stitchwort).

Biocontrol potential. Although it feeds on various species of plants sometimes considered "weeds," C. flaveola has a minimal potential as a biocontrol agent (at least in North America) due to its rarity and its incapability to build up to large populations which could affect the growth or dispersal of weeds. In Poland, Kosior (1975) found that C. flaveola does have an impact on Stellaria media . He found that all four species of Cassida that he studied can develop in large numbers under favorable conditions and hence (pp. 371), "a very real possibility occurs of using beetles and larvae of these species in the control of troublesome weeds."

Locality records. A total of 36 specimens were examined.

NOVA SCOTIA: Colchester Co.: Truro, 6.VII.1982, L.H. Lutz & M.A. Bulger, (2, NSAC); Truro, 3.VII.1984, J.A. Adams, (1, NSAC); Bible Hill, 31.V.2005, S.M. Townsend, pasture, (10, CBU); Bible Hill, 14.VI.2005, S.M. Townsend, pasture, (5, CBU); Bible Hill, 23.VI.2005, S.M. Townsend, pasture, (8, CBU); Bible Hill, 30.VI.2005, S.M. Townsend, pasture, (1, CBU); Bible Hill, 14.VII.2005, S.M. Townsend, pasture, (1, CBU); Bible Hill, 21.VII.2005, S.M. Townsend, pasture, (4, CBU); Bible Hill, 28.VII.2005, S.M. Townsend, pasture, (2, CBU); Bible Hill, 12.VIII.2005, S.M. Townsend, pasture, (1, CBU); Bible Hill, 3.VIII.2007, C.W. D'Orsay, pasture on Stellaria graminea , (6, CNC). PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND: Queens Co.: Wood Islands, 30.VI.2003, C.G. Majka, seashore, (1, CGMC).

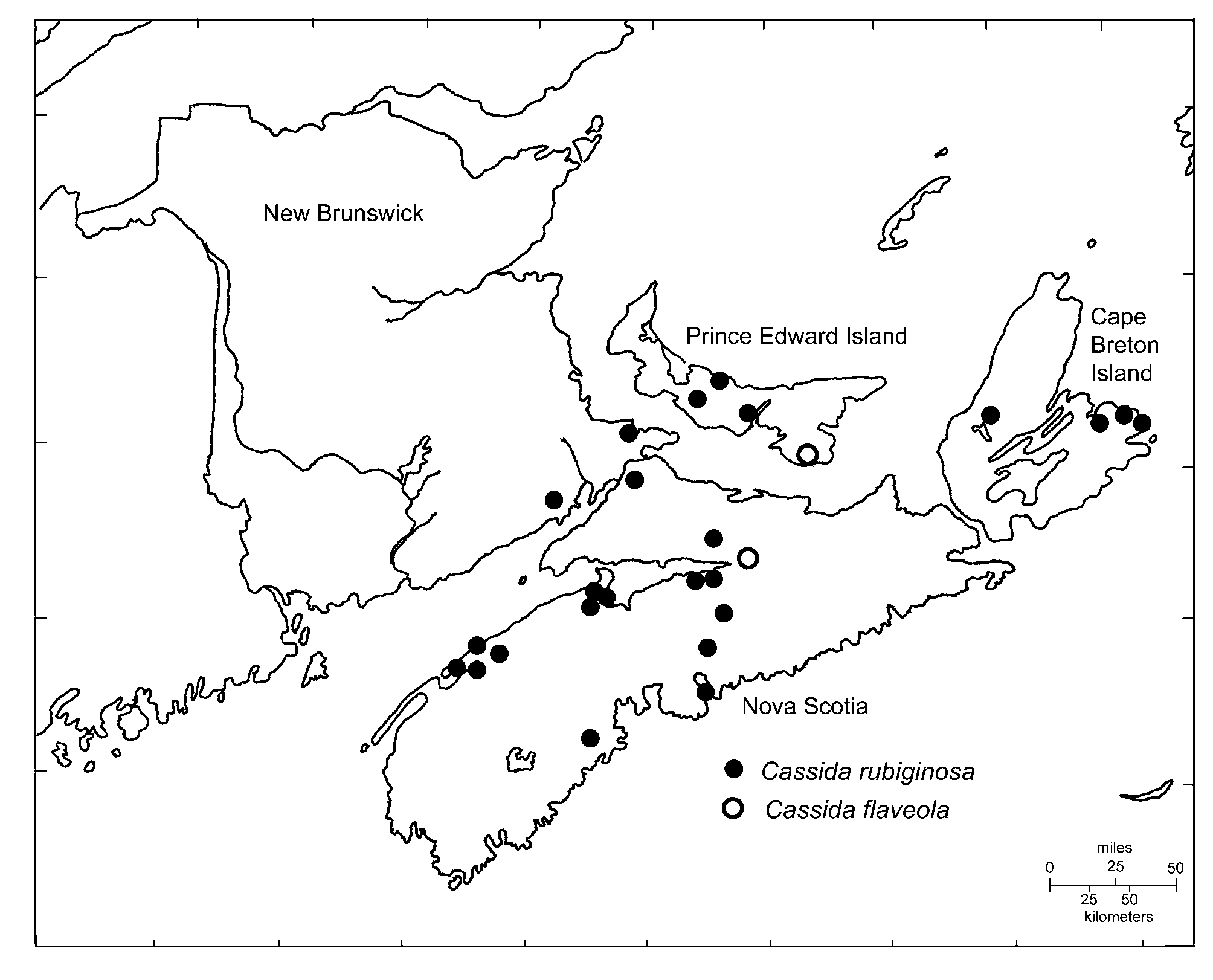

Distribution. The collection sites of C. flaveola in the Maritime Provinces are indicated in Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 . The species is newly recorded on Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and in the Maritime Provinces as a whole and has been recorded in the region from at least 1982.

The discovery of C. flaveola at Woods Islands, PEI poses interesting questions. It was found in coastal dunes adjacent to the Northumberland Ferries terminal which connects Prince Edward Island to Nova Scotia by ferry. This is an important transportation corridor and raises the possibility that it may have been introduced via human-assisted dispersal. Scymnus tenebrosus Mulsant , a native coccinellid, has also been found at Wood Islands. It is otherwise absent on PEI, prompting Majka and McCorquodale (2006) to consider whether its presence there may have been assisted by human activities. Similarly, the introduced carabid, Ophonus puncticeps (Stephens) , has been found at Caribou, the Nova Scotia terminus of this same ferry route, prompting Majka et al. (2006) to consider if human agency was responsible for its presence at that site. Majka & Klimaszewski (2004) and Majka & LeSage (2006) both discuss seaports and transportation corridors in the region as conduits for the introduction of Coleoptera . Further fieldwork in the Maritime Provinces would be desirable to better understand the status of this species in the region.

Zoogeography. Although Barber (1916), Lindroth (1957), Riley (1986), LeSage (1991), and Riley et al. (2003) have all regarded C. flaveola as a Palearctic species introduced, or probably introduced, to North America, there is reason to reconsider this supposition. As Riley (1986b) points out, "considering its wide range in North America and the fact that its site of introduction and subsequent spread has not been documented, the possibility that its natural range includes the Nearctic can not be rejected." Supporting this are the archeological discoveries reported by Matthews & Telka (1997) of fossil specimens of C. flaveola in sediments at Ch'ijee's Bluff, Yukon from the mid-Wisconsinian glaciation circa 52,000 years B.P. (and possibly also from the Interglacial period 125,000 years B.P.), as well as from Cape Deceit in western Alaska, from the late Pleistocene, circa 1.8 million years B.P. This clearly establishes C. flaveola , at least in part, as a Holarctic species (not excluding the possibility of later, additional human-assisted introductions). Thus its present range in North America might be a composite of indigenous, Holarctic populations, and more recent adventive ones. Further research would be required to resolve this question.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |