Tortricidrosis inclusa Skalski, 1973

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4394.1.2 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:6AEE9169-0FC2-4728-A690-52FFA1707FC0 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B2FF08-FFCA-140F-FF54-807F10DDFB64 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Tortricidrosis inclusa Skalski, 1973 |

| status |

|

Tortricidrosis inclusa Skalski, 1973 View in CoL

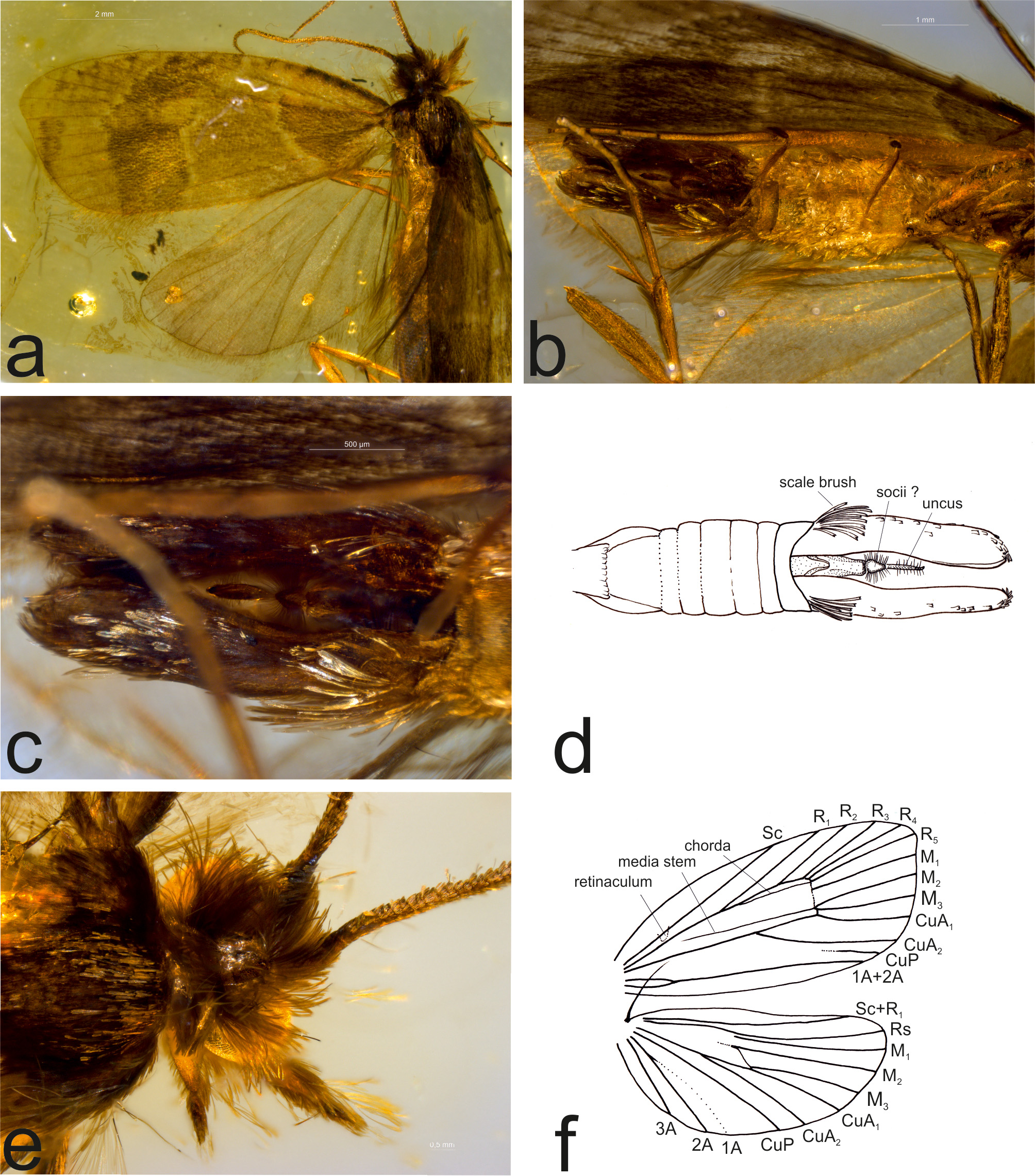

Excavation locality and depository: MNHU Berlin (Holotype: MB L-10=LEP.SUCC.133/AWS)/ Baltic Region (Baltic Amber, Prussian Fm.)/Lutetian, Middle Eocene. The amber collection of C. and H.W. Hoffeins includes a male tortricid moth in Baltic Amber (nr. 1649/3 coll. C. & H.W. Hoffeins (Hamburg) Baltic Region (Baltic Amber, Prussian Fm.)/ Lutetian, Middle Eocene) that WM suspects is conspecific with the holotype of T. inclusa . He simultaneously compared the two specimens under a dissecting scope at MNHU and could find no differences, except in forewing length, which is slightly larger in the specimen from the Hoffeins collection. Based on their morphological similarity and their comparable age, it is possible, that the two fossils are conspecific ( Figs 1 View FIGURE 1 a–f.). In the absence of morphological characters to separate or diagnose the two, we treat them as conspecific.

Published illustrations of holotype: Skalski 1973: 339, figs 1–5 (photographs and drawings).

Condition: The holotype is in a rectangular block (10 × 17 × 4 mm) of amber attached to a microscope slide. It is an adult male moth, forewing length 5.1 mm. The head, thorax and part of the wings are partly covered in a white substance that makes observation of details difficult. The wings are partly folded, and the veins are only partly visible. The fossil moth has retained some of its wing pattern, which is rare in fossils of Lepidoptera .

The specimen in the C. & H.W. Hoffeins collection is much better preserved than the holotype and reveals several characters that are unobservable in the holotype. It is also a male, and the right wings are perfectly spread, showing a fairly complete forewing pattern ( Fig. 1a View FIGURE 1 ).

Comments: Skalski (1973) presented an illustration of the forewing pattern of the holotype, which includes a basal spot, a median fascia, and a subapical spot, which are found in many species of Tortricidae . He also provided a reconstruction of the venation and descriptions of other visible details.

Based on the second specimen, the following characters can be added to the description of T. inclusa : antenna with short cilia on the ventral side, dorsal side of all flagellomeres with two rows of short scales; ocelli absent; maxillary palpus 3-segmented; haustellum base devoid of scales, short blunt sensilla in the apical portion; tarsal segments with three apical spines ventrally; male genitalia with extremely long valvae, nearly as long as the entire pregenital abdomen, with a long, slender, apically hooked uncus, and short socii.

Skalski (1973) suggested that T. inclusa was a member of the extant subfamily Olethreutinae based on the presence of infracellular veins [= the chorda and M stem], “the tendency to straighten the median and cubital veins,” and M 2 and M 3 straight, with their bases widely separate in the hind wing. The last character is typical of many tortricids and probably represents the plesiomorphic condition in the family. M stem and stem of R 4+5 also are present in some Tortricinae such as Cerace Walker, 1863 (Ceracini; from Eastern Palaearctic), Anacrusis Zeller, 1877 (Atteriini; South and Central American) and in some species of the Australian Arotrophora group ( Horak 1984).

Importantly, the flagellomeres of the antennae have two conspicuous rows of scales on the dorsal side. This newly discovered character excludes T. inclusa from Olethreutinae, which have a single row of scales on flagellomeres ( Horak & Brown 1991). The form of the labial palpi, the wing venation, the presence of abdominal scale brushes and the extraordinarily long valvae in the male genitalia suggest that Tortricidrosis should be placed in Chlidanotinae rather than in Tortricinae . Among tortricids in general, many Polyorthini are characterized by extremely long valvae. However, the absence of ocelli is somewhat problematic. Most Chlidanotini and Hilarographini have large ocelli, as do most Polyorthini ; ocelli are reduced in a few members of the latter (e.g. Ebodina Diakonoff, 1968 ), but they also are reduced or obsolete in most Schoenotenini (Tortricinae) ( Horak 1998) and in Amorbia Clemens, 1860 ( Phillips-Rodriguez & Powell 2007). The chorda is less troublesome as it is present or absent in Chlidanotini ( Brown 1990; Horak 1998). The somewhat “shaggy” scaling of the head is also troublesome, more similar to that of Tineidae than to Tortricidae .

The monophyly of Chlidanotinae has been challenged, and two recent studies based on molecular data suggest that the subfamily is paraphyletic ( Regier et al. 2012; Fagua et al. 2017). Although the subfamily of this fossil cannot be determined for certain, we conclude that it most likely is a tortricid.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |