Equus grevyi, Oustalet, 1882

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5719778 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5719804 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B0E520-E815-5860-FF1A-AC47ECEDF4E7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Equus grevyi |

| status |

|

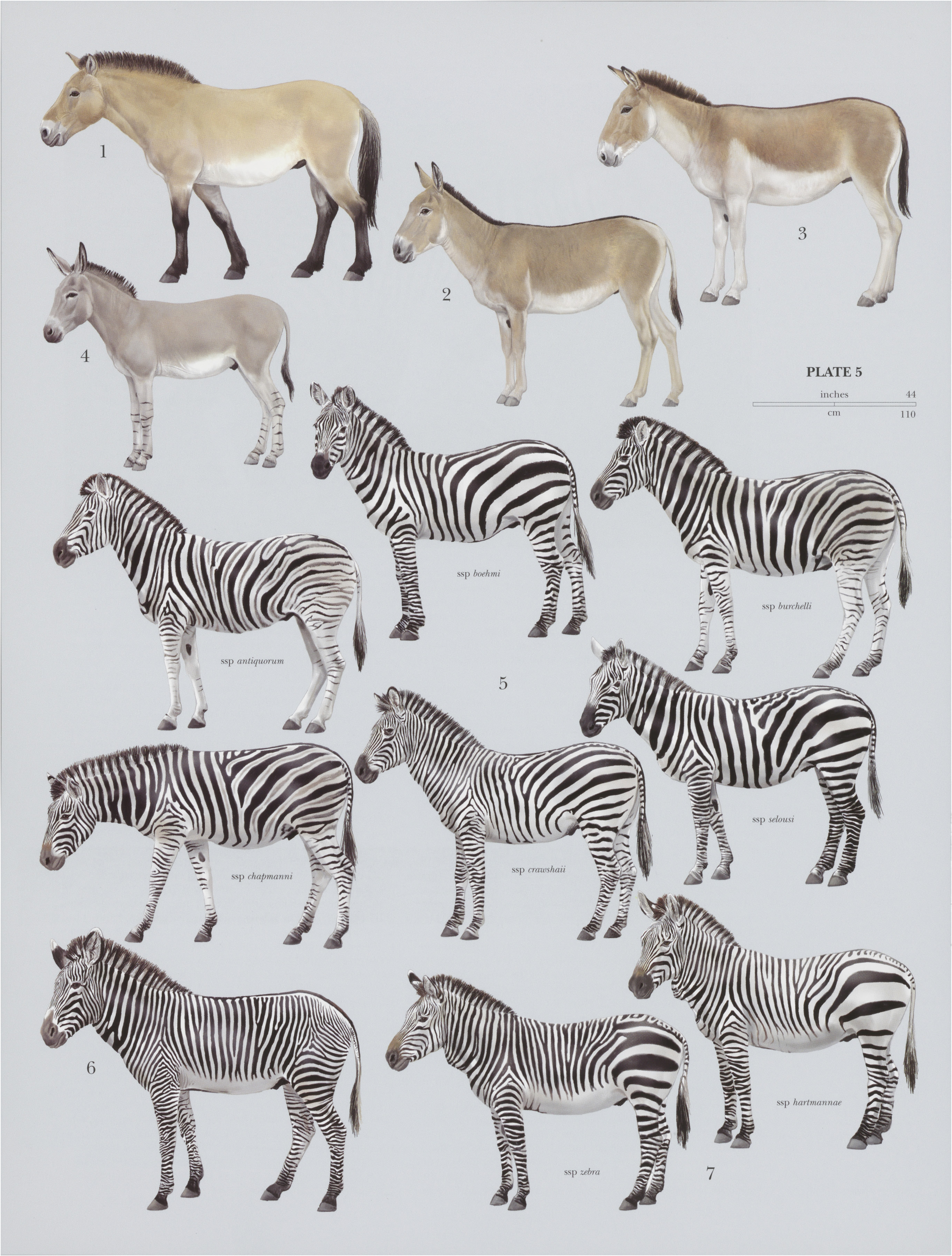

6 View On .

Grevy’s Zebra

French: Zebre de Grévy / German: Grévy-Zebra / Spanish: Cebra de Grévy

Other common names: Imperial Zebra

Taxonomy. Equus grevyi Oustalet, 1882 View in CoL ,

Ethiopia, Galla Country.

Grevy’s Zebra was described by French zoologist E. Oustalet and named after French President J. Grévy, who received the zebra as a gift from the Abyssinian government. Most DNA analyses agree that Grevy’s Zebra is in the same clade as the Plains Zebra ( E. quagga), and the Mountain Zebra (FE. zebra ). Most studies also concur that the Mountain Zebra was the last species in the clade to evolve, but it remains unclear whether Grevy’s Zebra or the Plains Zebra appeared first, because there are so few nucleotide differences between them. The species differ in chromosome number, Grevy’s Zebras having 46 and Plains Zebras 44, but they are so close evolutionarily that fertile hybrids have appeared at the southern edge of the Grevy’s Zebra's range. Monotypic.

Distribution. Ethiopia and C & N Kenya; perhaps also in S Sudan. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 250-275 cm, tail 38-75 cm, shoulder height 140-160 cm; weight 350-450 kg. Grevy’s Zebra is the largest of the equids, with a large head, long face, and elongated nostril openings. Its ears are large and round and can rotate independently in different directions. It has narrow stripes on its face, body, and rump; the stripes on the neck are slightly broader. The belly is white, as is the area around the base of the tail. Its muzzle is distinctively brown. It has an erect mane and the tail is tufted at the tip. Its hooves are large and rounded.

Habitat. Grevy’s Zebra inhabits semi-arid grasslands and thornbush scrublands typified by acacias and commiphoras. It does not need to drink daily and lives in habitats intermediate between the arid habitats of the true desert-dwelling African Wild Ass (FE. africanus ), and the more water dependant Plains Zebra , which inhabits mesic tropical grasslands. Lactating females stay in the most open areas around water; non-lactating females and territorial males prefer grassy areas with light tree cover. Bachelor males grade into areas of medium or moderate bush, but overall, Grevy’s Zebras avoid densely wooded areas except during periods of extreme drought.

Food and Feeding. Grevy’s Zebras are predominantly grazers, but browse can account for up to 30% oftheir diet during drought or when foraging on landscapes degraded by livestock. They move through habitats quickly, taking many steps per bite, selectively choosing certain grass species over others. As a result, when grazing herds of Grevy’s and Plains Zebras form, the herds don’t persist for long, since Grevy’s Zebras simply pass through them. Availability of water and individual water requirements ultimately determine where Grevy’s Zebras can forage. Since non-lactating females can go without water for up to five days, they typically range far from water, seeking out previously well-watered areas with large quantities of vegetation. Lactating females, with their need to produce milk, must drink daily. Thus they remain near water, feeding on closely cropped grazing lawns that offer forage of high nutritive quality even if the amount of available food is limited.

Breeding. Grevy’s Zebras can breed year-round, but most births are timed to coincide with the arrival of the long rains that normally fall between April and June. Where Grevy’s Zebras reside, two rainy seasons are expected, since the intertropical convergence zone sweeps across the Equator twice per year. But often one or more of the rains fails. This severely limits the species’ ability to rebound after environmental or anthropogenic shocks. When females are in estrus they typically move through many male territories. Males only mate when on their own territories, and because females rarely stay with one male, Grevy’s Zebra males engage in post-copulatory sperm competition. Therefore, not surprisingly, they have larger testes than the other zebra species. To help ensure that they can mate with as many females as possible, when there are no females on their territories, territorial males wander widely in search of bachelor males and aggressively challenge them. By preemptively reinforcing dominance in low-risk settings, territorial males are able to devote more time to mating than to fighting when bachelors invade territories containing many females.

Activity patterns. Grevy’s Zebras are opportunists and move great distances in search of food and water. Females and their young, as well as bachelor males, have large home ranges, often moving with the rains to areas where grass is growing or abundant. Territorial males tend to linger on their territories until well after all other zebras have left and only depart when conditions have deteriorated dramatically. During normal dry seasons, when all Grevy’s Zebras are dependent on water, concentrations of males and females develop. Given that Grevy’s Zebras often move 35 km per day if food and water are widely separated, aggregations tend to split apart and are never very large. Sightings of a few hundred Grevy’s Zebras at a time are rare. Although the availability of food and water determine most movements, predation plays a role. Grevy’s Zebras avoid human settlements during the day because of stresses associated with human activity, but at night settlements are sought as refuges against predators.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Grevy’s Zebras differ socially from the other two species of zebras; they do notlive in closed-membership family groups, or harems. Like the asses, Grevy’s Zebras live in open-membership groups in which the only long-lasting bond is between mothers and their young. Adult females come together at water sources and good grazing sites and continue to travel together as long as their needs can be satisfied. When they cannot, such as when lactating females need to return daily to water and those without young or with older young do not, then the social ties that bind females become severed and groups dissolve. Given that both types of females are sexually active, and males cannot simultaneously associate with both, dominant males instead establish territories adjacent to water. In this way high-status males have mating access to both lactating and non-lactating females whenever they come to water. Less dominant males also establish territories, but in areas of abundant vegetation far from water, where they gain access to the subset of females searching for quality foraging areas. Territories can be as large as 10 km?, the largest of any equid. Males of the lowest rank are unable to maintain territories, so they join bachelor groups. They range widely, grow quickly, and by interacting with many males they improve their fighting ability.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Grevy’s Zebras exist only in the Horn of Africa. According to recent surveys, an estimated 2000-2300 live in Kenya, around 150 in Ethiopia, and there may be a few in southern Sudan. Historically Grevy’s Zebras ranged more widely, from Somalia to western Ethiopia, Djbouti, and Eritrea, and from southern Ethiopia south tojust north and west of Mount Kenya. Extensive hunting ceased at the start of the 1980s, yet populations of Grevy’s Zebras did not rebound. They are still decreasing and from 1988 to 2007, the global population declined approximately 55%. Increasing competition with the livestock of pastoral herders for water and forage appears to be the culprit. As human populations and their herds grew, water disappeared more quickly than in the past. In addition, the presence of humans and livestock prevented the zebras from accessing drinking sites during the day. Constrained lactation, in addition to greater predation risks associated with night-time drinking, reduced infant and juvenile survival. Since less than 5% of Grevy’s Zebra’s current range is located within protected areas, the best hope for enhancing population growth involves encouraging communities to better manage rangelands, as well as increasing the value of Grevy’s Zebras by training community members to become scouts or ambassadors and hiring them to help monitor Grevy’s Zebra population dynamics and harmful human impacts.

Bibliography. Cordingley et al. (2009), Ginsberg & Rubenstein (1990), Groves (2002), Kingdon (1997), Klingel (1974), Low et al. (2009), Moehlman, Rubenstein & Kebede (2008), Rowen & Ginsberg (1992), Rubenstein (1986a, 1986b, 1994), Sundaresan et al. (2008).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.