Equus africanus, Heuglin & Fitzinger, 1866

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5719778 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5719800 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B0E520-E813-5861-FA63-A123EFB2F480 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Equus africanus |

| status |

|

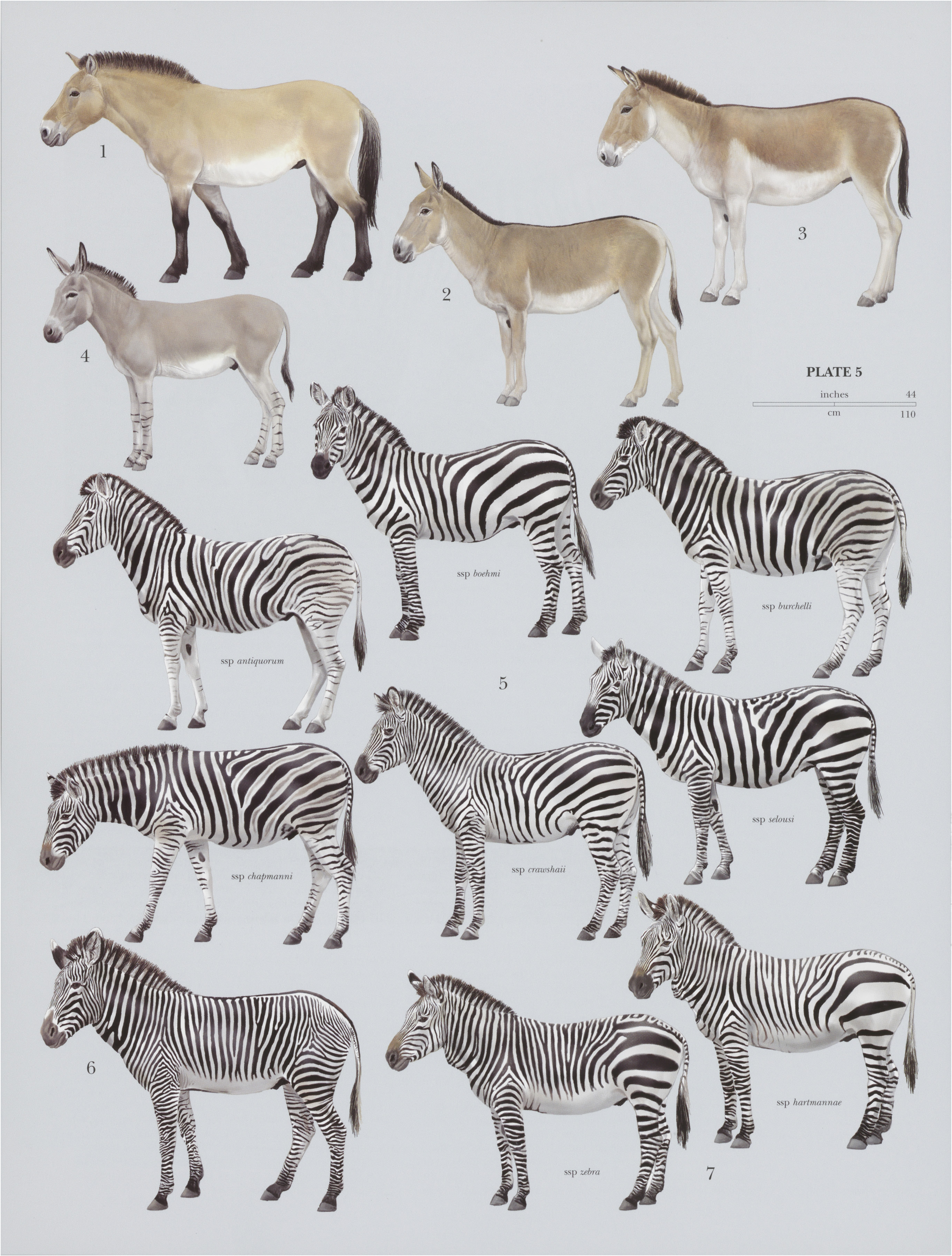

4 View On .

African Wild Ass

French: Ane sauvage / German: Afrikanischer Wildesel / Spanish: Asno salvaje

Other common names: Atlas Wild Ass (atlanticus), Nubian Wild Ass ( africanus ), Somali Wild Ass (somalicus)

Taxonomy. Asinus View in CoL africanus Heuglin & Fitzinger, 1866 View in CoL ,

Nubia. Restricted to Ain Saba, Eritrea, by Schlawe in 1980.

The “Atlas Wild Ass” race atlanticus (Thomas, 1884) from North Africa is extinct. Two extant subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

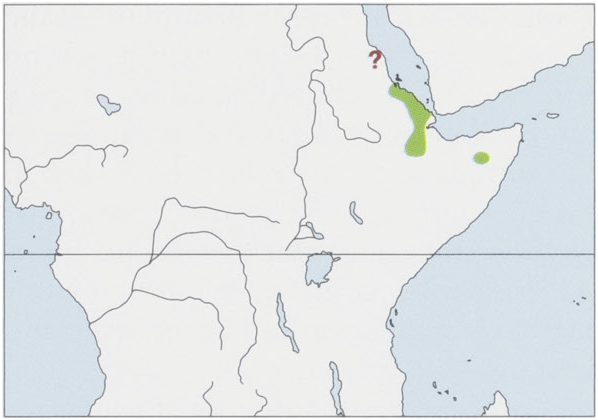

E. a. somalicus Sclater, 1885 . — Eritrea (Denkelia region), NE & E Ethiopia (Danakil Desert, Awash River Valley, and Ogaden), W Djibouti, and Somalia from the Meti and Erigavo in the N to Nugaal Valley and Shebelle River in the S. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 195-205 cm, tail 40-45 cm, shoulder height 115-125 cm; weight 270-280 kg. The African Wild Ass is the ancestor of the domestic Donkey ( E. asinus ). It is strong, lean, and muscular, with a fawn or gray coat dorsally and a white belly and legs. It has long ears, a stiff erect mane,a tail ending with a tuft of black hair, and extremely narrow hooves that appear designed for surefootedness rather than speed. The “Nubian Wild Ass” is gray with a shoulder stripe; the “ Somali Wild Ass”is gray and has both leg and shoulder stripes.

Habitat. The African Wild Ass inhabits hilly and stony deserts as well as semi-desert grasslands and euphorbia and aloe shrublands that receive 100-200 mm of rainfall annually. Sandy habitats are avoided. Recorded up to 1500 m of elevation in Ethiopia.

Food and Feeding. The African Wild Ass mostly grazes, eating grasses, especially Eragrostis, Dactyloctenium, and Chrysopogon when available, and tougher Panicum and Lasiurus species, as well as herbs and general browse. The asses use their incisors and hooves to break apart the tougher foods. Although they can sustain water losses of up to 30% of their body weight, they can replenish these losses within two to five minutes. Nevertheless, they need to drink water at least once every three days and most individuals are observed within 30 km of a water source.

Breeding. Although the age of first estrus has not been documented in African Wild Asses, in feral asses, first estrus occurs at about twelve months of age. Most females, however, give birth at 2-2-5 years of age and give birth to one foal every other year thereafter. Females cycle every 20-21 days until they conceive and gestation ranges from 330 to 365 days. Foals are independent soon after birth, often remaining alone for long periods as mothers seek water to maintain lactation. Foals begin grazing within weeks of birth but typically suckle for six months. Males tolerate other males within their territories even when females are present; dominance ensures that mating access is controlled mostly by territory holders. Breeding occurs during the wet season, with most births between October and February. The life span of wild asses is thought to be around 25-30 years.

Activity patterns. The species is most active in the early morning, late afternoon, or at night, when the desert is cooler. During the hottest part of the day it seeks shade in nearby rocky hills whereit rests. Its body temperature can range from 35°C to 41-5°C, depending on ambient temperature. Females maintain higher body temperatures than males by sweating less, thus retaining water longer.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. African Wild Asses live in small groups that are typically composed of fewer than five individuals. Associations are usually temporary, with the only permanent one consisting of a mother and her young. Gatherings occur at watering places or when searching for scarce forage. Low food availability and poor-quality forage prevent females from feeding in close proximity and associating consistently. Temporary groups vary in composition, sometimes containing only members of a single sex, sometimes members of both sexes. Breeding males defend large territories with essential resources, especially water, that females need. Males associate with females who enter their territories, and the better the territory, the longer females will stay, thus increasing a territorial male’s reproductive success. When conditions on a territory are not yet attractive to females, territorial males are found alone or occasionally in bachelor male groups. Territories are often 20 km? in size, with boundaries marked by conspicuous dung piles. Females range more widely, readily moving among male territories.

Status and Conservation. CITES I. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Formerly, the African Wild Ass was distributed across large stretches of northern Africa, but now only occupies a small part ofits historic range. The Atlas Wild Ass occupied the north-west region of Algeria and adjacent parts of Morocco and Tunisia, becoming extinct around 300 ap. Threats to its survival come from hunting for food and body parts used in traditional healing, competition with livestock for food and water, and possible interbreeding and introgression from the domestic donkey. Fewer than 600 individuals of the Somali Wild Ass are thoughtto survive in the wild. Only Eritrea, where up to 400 individuals may survive,is thought to have a stable population. Fewer than 160 are believed to survive in Ethiopia, and fewer than ten in Somalia. The Nubian Wild Ass was present in the Nubian desert of north-eastern Sudan, from east of the Nile River to the Red Sea, south to the Atbara River and into northern Eritrea. However no sightings have been confirmed since the 1970s, and their survival in these regions is now in doubt.

Bibliography. Antonious (1938), Groves & Willoughby (1981), Kingdon (1997), Maloiy (1970), McCort (1980), Moehlman (1998, 2002), Moehiman, Yohannes et al. (2008), Wilson & Reeder (1993), Woodward (1979).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.