Equus przewalskii, Poliakov, 1881

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5719778 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5719782 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B0E520-E812-5867-FFAA-AB80EEA6F941 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Equus przewalskii |

| status |

|

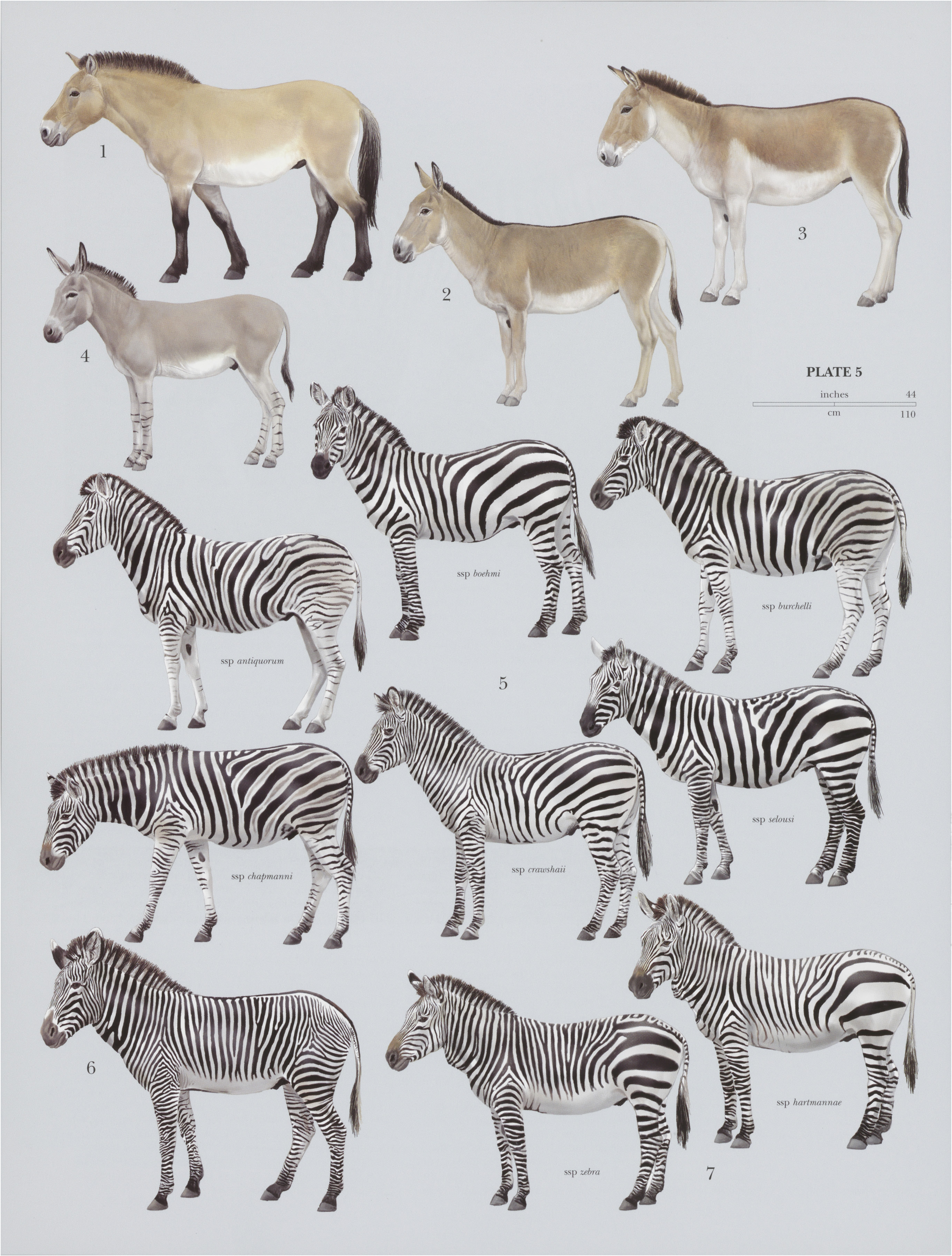

1 View On .

Przewalski’s Horse

French: Cheval de Przewalski / German: Przewalski-Pferd / Spanish: Caballo de Przewalski

Other common names: Asian Wild Horse, Dzungarian Horse, Mongolian Wild Horse, Takhi

Taxonomy. Equus przewalskii Poliakov, 1881 View in CoL ,

Gutschen, Chinese—Russian border.

The taxonomy of Prezwalski’s Horse is problematic and unresolved. C. P. Groves proposed that all horses surviving into modern times belonged to one species, E. ferus , with three subspecies: E. f. ferus (the “Tarpan”), E. f. sylvestris at the eastern edge of Eastern Europe, and E. f. przewalskii of Western Asia. Although feral descendants of the domestic Horse ( E. caballus ) roam freely in many locations around the world, Przewalski’s Horse is the only truly wild horse, although all its populations derive from reintroductions from zoos around the world. Analyses of nucleotide sequences on X and Y chromosomes place the two species in the same clade. Despite the fact that Prezwalski’s Horses have 66 chromosomes and domestic Horses have 64, introgression from interbreeding has occurred in the wild and in captivity. When coupled with the fact that Przewalski’s Horses have gone through a genetic bottleneck via captive breeding in zoos, the likelihood remains that it and the domestic Horse species today remain within the same clade. Monotypic.

Distribution. Limited to small populations that have been reintroduced to the Khustain Nuruu National Park, Takhin Tal and Khomin Tal Nature Reserves of Mongolia, and the Ka La Mai Li Shan Nature Reserve of China. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 220-280 cm,tail 99-111 cm (including hair), shoulder height 120-146 cm; weight 200-300 kg. Przewalski’s Horses are stockier than domestic Horses and have long tails, thick black erect manes that only fall to the side when very long, chestnuts on both hind and forelimbs, and large rounded hooves. Their coats are a uniform dusty or dun color on the body and flanks; the belly and face are yellowish-white, and there are traces of yellowish-white stripes just above the hooves. Przewalski’s Horses have a relatively small skull, with a long diastema, and a long, rounded occipital crest.

Habitat. The historic range of Przewalski’s Horse is not known. The last wild horse was seen in the very arid Dzungarian Gobi Desert in Mongolia, and there has been much debate about whether it was in its preferred habitat or justits last refuge. One view holds that of the three wild horse species that once inhabited the grasslands of Europe, Central Asia, and China, Przewalski’s Horse was the one that thrived at the easternmost edge of the range, where it encountered limited water and arid conditions as part of its natural habitat. Another view holds that these horses favored the more mesic grassland steppes of Mongolia, but as a result of more than a thousand years of competitive exclusion by nomadic pastoralists, they were forced into the deserts, where they fared poorly and died out. Domestic Horses do not fare well in dry climes, but ecological studies on feral horses show that some populations can survive in arid environments where food is scare and the best patches are often far from water. However, other studies show that populations survive and reproduce better in more mesic areas where vegetation is more abundant, more evenly distributed, and water is close to feeding areas. Grass and water are more plentiful in the mesic grasslands of Mongolia, but the winters there are harsher than in the Dzungarian Gobi. Today, populations of Przewalski’s Horses have been reintroduced into the mesic grasslands of central Mongolia as well as arid areas on the edge of the Gobi Desert and the Kalamaili Nature Reserve, which lies adjacent to the painted desert of China. Populations continue to survive in both xeric and mesic areas, although the population in China requires more active management than the ones in Mongolia.

Food and Feeding. Like feral horses, Przewalski’s Horses are grazers. They inhabit steppe vegetation, especially the grasslands and shrublands of Central Asia. In summer they consume high-quality forage near water. In the winter, however, they must subsist on more fibrous food that can be difficult to locate because of snow cover. Fortunately, strong winds often blow the snow away, making succulent vegetation available.

Breeding. Females come into estrus for the first time at two years of age, but usually do not breed until three. Males reach sexual maturity at three years old, but do not mate until 5-6 years of age, when they are able to dominate enough males so they can maintain long-term associations with mature females. As in domestic horses, females commence cycling in spring and continue cycling throughout the summer. Since gestation is 11-12 months (330-350 days), periods of breeding and birthing coincide.

Activity patterns. Przewalski’s Horses are active day and night, but generally sleep for four hours per day, mostly at night. In Mongolia, during the summer they are most active and move to streams and brooks to forage and drink. During the hottest times of the day they move up to ridge tops where cool breezes reduce attacks by biting flies. Przewalski’s Horses of the Khustain Nuruu National Park in Mongolia coexist with Gray Wolves (Canis lupus). Foals are at the highest risk, and when wolves are detected, females, both mothers and non-mothers, form a defensive circle around the foals. As long as three or more females are present, foal chances of survival are high.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Przewalski’s Horses exhibit many of the same behaviors as feral horses. Females live in family groups that associate with a single breeding male. These harems move within large home ranges that overlap those of other family groups. Males unable to form long-term associations with females live in all-male bachelor groups whose membership is more fluid than that of family groups. Competition among males over mating access to females is common, yet ritualized signaling before escalating to physical violenceis the norm. Males typically mark the urine of females with their own urine and they repeatedly defecate in communal dung piles along well-traveled routes as a way of indicating and assessing how recently other males were present. Both sexes disperse from their natal groups upon reaching sexual maturity. As populations expanded at release sites, home ranges changed from virtually non-overlapping areas of 200-1100 ha to overlapping ranges averaging 1000 ha in size. Ranges tend to be larger in summer.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List. It was classified as Extinct in the Wild until 2008, but since then a series of reintroductions have created free ranging populations in both mesic and arid environments in Mongolia and China. It likely once roamed the steppes of China and Central Asia; there are written accounts from Tibet from around 900 Ap. Small groups of horses were reported through the 1940s and 1950s in Mongolia, but numbers appeared to decline dramatically after World War II. The last confirmed sighting in the wild was made in 1969 near a spring called Gun Tamga, north of the Takhin-Shara-Nuruu, in the Dzungarian Gobi. Since the late 1970s, matings of captive animals have been managed world-wide, with the goal of maintaining over 95% of the existing genetic diversity for the next 200 years. Preventing the rapid loss of genetic diversity has helped enhance the genetic potential of free ranging populations. In 2008 there were approximately 325 free-ranging reintroduced and native-born Przewalski’s Horses in Mongolia. All Przewalski’s Horses alive today are descended from only 13 or 14 individuals, which were the nucleus of a captive breeding program. In China, the Wild Horse Breeding Centre (WHBC) in Xinjiang has established a large captive population of approximately 123 Przewalski’s Horses. Since 2007 one harem group 1s roaming free on the Chinese side of the Dzungarian Gobi; another 60 horses are roaming free during summer time but all return to the acclimatization pen during the winter.

Bibliography. Ballou (1994), Berger (1986), Bokonyi (1974), Boyd & Houpt (1994), Boyd et al. (2008), Dierendonck et al. (1996), Groves (1994), Rubenstein (1986a, 1986b), Ryder & Chemnick (1990), Zimmerman & Ryder (1995).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.