Equus hemionus, Pallas, 1775

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5719778 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5719786 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B0E520-E812-5866-FABE-ACFDEF26F67F |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Equus hemionus |

| status |

|

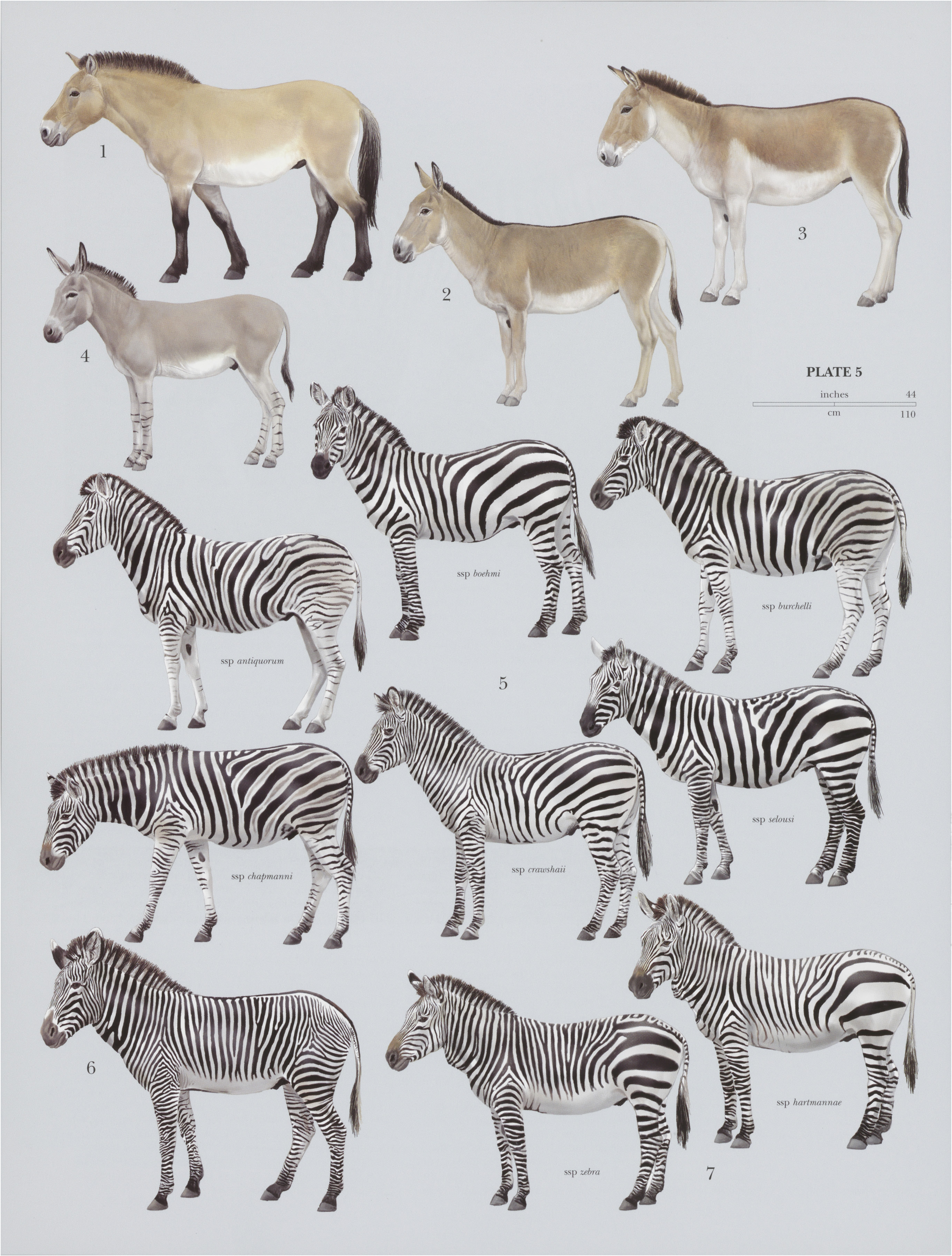

2 View On .

Asiatic Wild Ass

French: Hémione / German: Asiatischer Halbesel / Spanish: Onagro

Other common names: Onager ; Gobi Kulan (luteus), Khur (khun, Kulan (kulan), Mongolian Kulan ( hemionus ), Persian Onager ( onager ), Syrian Onager ( hemippus )

Taxonomy. Equus hemionus Pallas, 1775 View in CoL ,

North-eastern boundary of Mongolia with Russia, Transbaikalia, S. Chitinsk , 50° N, 115° E. GoogleMaps

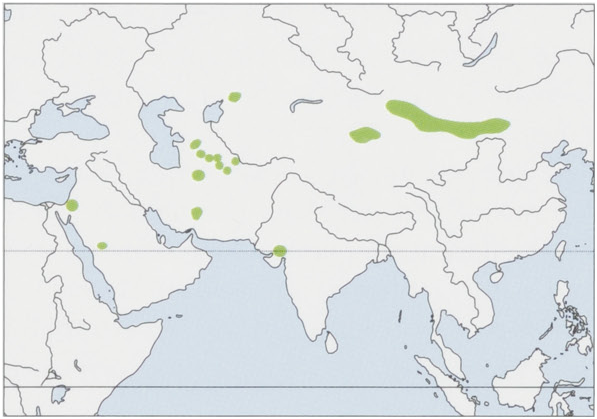

The “Syrian Onager ” race hemippus (Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1855) from Syria and the Arabian Peninsula is extinct. The “Gobi Kulan” luteus is probably a synonym of the nominate race hemionus . Four extant subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

E. h. hemionusPallas, 1775 — SMongoliaandextendingintoNChina.

E. h. khurLesson, 1827 — LittleRannofKutch, Gujarat, India.

E. h. kulanGroves & Mazak, 1967 — KazakhstanandTurkmenistan (Badkhyzregion).

E. h. onager Boddaert, 1785 — two reserves in Iran (Touran and Bahram-e-Goor), Israel (Negev Desert), and Saudi Arabia (Taif). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 200-250 cm, tail 30-49 cm, shoulder height 126— 130 cm; weight 200-260 kg. Asiatic Wild Asses are characterized by reddish-brown coats in the summer that become paler brown, sandy, or even gray in the winter, depending on subspecies. The flanks and belly are white and some subspecies have a dark brown stripe running along the back. The mane is black and erect and consists of short bristly hair. The tail is short, with a tuft of long hairs at the tip. The legs are short and thin when compared to other equid species. The hooves are broader and rounder than those of the African Wild Ass ( E. africanus ) and are the most horse-like of all the asses. Males are slightly larger than females. The subspecies differ in skull morphology. The Transcaspian and Mongolian forms have narrower supraoccipital crests than the Iranian and Indian forms. The Asiatic Wild Ass can reach speeds up to 70 km /h.

Habitat. Asiatic Wild Asses live in xeric habitats where rainfall is limited. Many of the subspecies live in flat semi-deserts with extremely hot days and cool nights.

Food and Feeding. When grass is abundant, Asiatic Wild Asses are primarily grazers. During the dry season, or in the driest habitats, they will switch to browse, even consuming woody parts of plants. They also eat seedpods and will use their hooves to break apart woody material to reach succulent forbs. In Mongolia, asses often eat snow in the winter as a substitute for drinking water and have been known to dig holes 60 cm deep to reach water in the summer.

Breeding. Gestation in Asiatic Wild Asses is eleven months and breeding is highly seasonal. Births peak during April and September, depending on subspecies and location. Within any one population births occur within a 2-3 month period. Females reach puberty at three years of age and give birth to only one foal at a time. Foals generally stay with their mothers for two years.

Activity patterns. Asiatic Wild Asses are most active at dawn and dusk, when temperatures are cooler. Although they obtain most of their water from food, they are almost always seen within 30 km of water. Lactating females in particular need to drink frequently; at least once per day.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The ranging and social behavior of Asiatic Wild Asses is highly variable. Many populations show seasonal movements. Male Asiatic Wild Asses in Israel return each spring to breeding areas several weeks before females, typically to claim territories held the previous year. The territories of dominant males are generally distributed around water points. Males unable to defend territories either form all-male bachelor groups or remain on the winter grazing grounds. Females coalesce into groups on the breeding grounds, but the groups are fluid. When populations contain many territorial males, some females move frequently among territories, suggesting that some of them move in search of mating opportunities as well as key resources. Others, especially those with young foals, remain on the territory of one male. Some subspecies, such as the “ Khur ” of India, exhibit the same types of social associations as do the Israeli Asiatic Wild Asses, but members of both sexes remain in one area year-round. Others, such as the “Kulan” of the Gobi, exhibit more horse-like social behavior, in which females and their offspring live in closed membership groups and travel to and from water with one male. Males in the Gobi population actively herd females if they stray too far, a behavior not seen in the Khur of the Little Rann of Kutch. Kulan males in the Gobi also defend females and their young from predators, suggesting that some interspecific variation in social organization is related to predation threat.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I (subspecies hemionus and khur ) and the rest listed in Appendix II. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. The Syrian Onager , went extinct in 1927. The largest population of Asiatic Wild Asses in the world is currently in southern Mongolia, and makes up almost 80% of the global population. The “Mongolian Kulan” population was estimated in 2003 at 18,411 + 898 in four areas. There are estimates of 4800-6000 Kulan in the Kalameili Reserve in China, but they may be a population migrating seasonally from Mongolia. The next largest subpopulation is the Indian Khur , estimated in 2004 at 3900, in the Little Rann of Kutch. Thisis the only subpopulation of the Asiatic Wild Ass that has steadily increased in size from 1976 to the present day. In 2005 the Kulan populations consisted of about 1300 animals in Turkmenistan (850-900 in Badkhyz Reserve and 445 in seven reintroduction sites). In 1991 the reintroduced population in Uzbekistan in Dzheiran Ecocentre numbered 34. There is limited information on the status of the “Persian Onager ” in Iran, but recent estimates give a figure of 600 in the two protected areas (471 animals in Touran National Park in 2000, 96 in Bahramgor Reserve in 1996, and four reintroduced animals in Yazd Province in 2000). There were also five reintroduced onagers in Taif ( Saudi Arabia) in 2000, and a further 100 reintroduced animals in Israel in the same year. The global population of mature Asiatic Wild Asses has fallen in the last 16 years by 52%, the current estimate of mature individuals being 8358. Today in Iran, the Persian Onageris threatened by poaching, overgrazing by livestock, and by competition with livestock at watering points. Shrub removal also degrades the habitat. Khur are threatened by competition with livestock as well as other economic activity such as salt mining and canal building. Kulan have experienced rapid declines in numbers because of increased demand for bushmeat. The threat from pastoralists who complain that Kulan are reducing forage for livestock is increasing. Trophy hunting does not appear to be a problem.

Bibliography. Asa (2002), Feh, Munkhtuya et al. (2001), Feh, Shah et al. (2002), Goyal et al. (1999), Moehlman, Shah & Feh (2008), Reading et al. (2001), Saltz & Rubenstein (1995), Saltz et al. (2000).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.