Canis aureus, Linnaeus, 1758

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6331155 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6335027 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03ACCF40-BF31-FFCE-7B99-F4A8F7E6DBEA |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Canis aureus |

| status |

|

Golden Jackal

French: Chacal doré / German: Goldschakal / Spanish: Chacal dorado

Other common names: Asiatic Jackal, Common Jackal

Taxonomy. Canis aureus Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

Iran.

As many as twelve subspecies are distinguished across the range. However, there is much variation and populations need to be re-evaluated using modern molecular techniques.

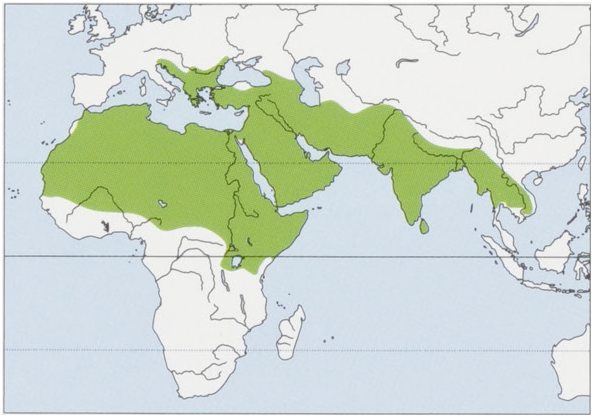

Distribution. Widespread in N and NE Africa, occurring from Senegal on the W coast of Africa to Egypt in the E, in a range that includes Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya in the N to Nigeria, Chad, and Tanzania in the S. They have expanded their range from the Arabian Peninsula into Western Europe, to Bulgaria, Austria, and NE Italy and E into Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Central Asia, the entire Indian subcontinent, then E and S to Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, and parts of Indochina. View Figure

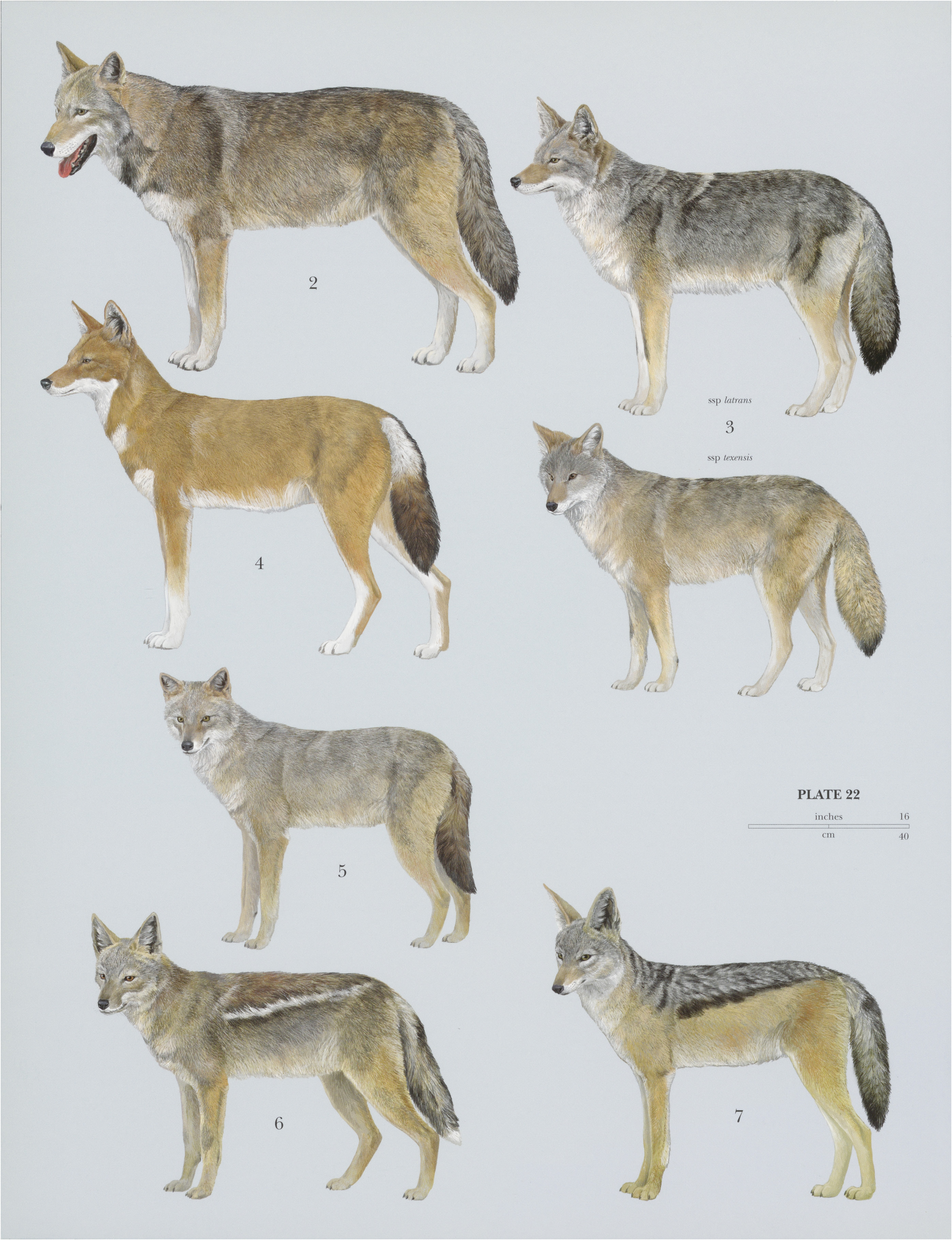

Descriptive notes. Head-body 76-84 cm for males and 74-80 cm for females, tail 20-24 cm for males and 20-21 cm for females; weight 7-6-9- 8 kg for males and 6-5-7- 8 kg for females. Medium-sized canid, considered the most typical representative of the genus Canis . Approximately 12% difference in body weight between sexes. Basic coat color is golden but varies seasonally from pale creamy yellow to a dark tawny hue. The pelage on the back is often a mixture of black, brown, and white hairs, giving the appearance of a dark saddle similar to that of Black-backed Jackals. Jackals inhabiting rocky, mountainous terrain may have grayer coats. The belly and underparts are a lighter pale ginger to cream. Unique paler markings on the throat and chest make it possible to differentiate individuals. Melanistic and piebald forms are sometimes reported. The tail is bushy with a tan to black tip. The legs are relatively long, and the feet slender with small pads. Females have four pairs of mammae. The skull is more similar to Coyote and Gray Wolf than to Black-backed Jackal, Side-striped Jackal, or Ethiopian Wolf. The dental formulais13/3,C1/1,PM 4/4, M 2/3 =42.

Habitat. Tolerance of arid zones and an omnivorous diet enable Golden Jackals to live in a wide variety of habitats. These range from the Sahel to the evergreen forests of Myanmar and Thailand. Golden Jackals occupy semi-desert, short to medium grasslands and savannahs in Africa, and forested, mangrove, agricultural, rural, and semi-urban habitats in India and Bangladesh. Golden Jackals are opportunistic and will venture into human habitation at night to feed on garbage. They have been recorded at elevations of 3800 m in the Bale Mountains of Ethiopia and are well established around hill stations at 2000 m in India.

Food and Feeding. An omnivorous and opportunistic forager, the Golden Jackal’s diet varies according to season and habitat. According to one study in east Africa, although they consume invertebrates and fruit, over 60% of Golden Jackal diet consisted of rodents, lizards, snakes, birds (from quail to flamingoes), hares, and Thomson's Gazelle (Eudorcas thomsoni). In India, over 60% of the diet comprised rodents, birds, and fruit in Bharatpur, while in Kanha over 80% ofthe diet consisted of rodents, reptiles, and fruit. In Sariska Tiger Reserve, India, scat analysis (n = 36) revealed that Golden Jackal diet included mainly mammals (45% occurrence, of which 36% was rodents), vegetable matter (20%), birds (19%), and reptiles and invertebrates (8% each). Golden Jackals often ingest large quantities of vegetable matter, and during the fruiting season in India they feed intensively on the fruits of Ziziphus sp., Carissa carvanda, Syzigium cuminii, and pods of Prosopis juliflora and Cassia fistula. Single jackals typically hunt smaller prey like rodents, hares, and birds. They use their hearing to locate rodents in the grass and then leap in the air and pounce on them; they also dig out Indian Gerbils (7atera indica) from their burrows. They have been observed to hunt young, old, and infirm ungulates that are sometimes 4-5 times their body weight. Although Golden Jackals are able to hunt alone, cooperative hunting in small packs of 2—4 individuals is often more successful and permits them to kill larger prey, including antelope fawns and langur monkeys (Presbytis pileata and P. entellus). Groups of 5-18 Golden Jackals have been sighted scavenging on carcasses of large ungulates, and there is a report of similar aggregations on clumped food resources in Israel. In several areas of India and Bangladesh, jackals subsist primarily by scavenging on carrion and garbage. They also cache food.

Activity patterns. Golden Jackals are mainly nocturnal, but have flexible activity patterns and may be active during the day. During Blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra) calving peaks in Velavadar National Park, India, for example, jackals were observed searching throughout the day for calves in hiding, searches intensifying during the early morning and late evening.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The social organization of Golden Jackals is extremely flexible and depends on the availability and distribution of food resources. The basic social unit is the breeding pair, which is sometimes accompanied by its current litter of pups and/or by offspring from formerlitters. In Tanzania breeding pairs usually form long-term bonds, and both members mark and defend their territories, hunt together, share food, and cooperatively rear the young. Of a total of 270 recorded jackal sightings in the Bhal and Kutch areas of Gujarat, India, 35% consisted of two individuals, 14% of three, 20% of more than three, and the rest of single individuals. Average group sizes have been reported as 2-5 (Serengeti, Tanzania) and 3 (Velavadar National Park, India). Scent marking by urination and defecation is common around denning areas and on intensively used trails, and is thought to play an important role in territorial defense. Recent telemetry data from the Bhal area in India suggest that most breeding pairs are spaced well apart and likely maintain a core territory around their dens. Feeding ranges of several Golden Jackals in the Bhal overlapped. Jackals were observed to range over large distances in search of food and suitable habitat, and linear forays of 12-15 km in a single night were not uncommon. Non-breeding members of a pack may stay near a distant food source like a carcass for several days prior to returning to their original range. Recorded home range sizes vary from 1- 1-20 km? depending on the distribution and abundance of food resources. Greeting ceremonies, grooming, and group vocalizations are common social interactions. Vocalizations consist of a complex howl repertoire beginning with two to three simple, low-pitched howls and culminating in a high-pitched staccato ofcalls. Jackals are easily induced to howl. A single howl usually evokes responses from several jackals in the vicinity. In the presence of large carnivores, Golden Jackals often emit a warning call that is very different from their normal howling repertoire. In India, howling is more frequent between December and April, a time when pair bonds are being established and breeding occurs, perhaps suggesting a role in mate attraction, mate guarding, or territory defense.

Breeding. Reproductive activity occurs from February to March in India and Turkmenistan, and from October to March in Israel. In Tanzania, mating typically occurs from October to December, with pups being born from December to March. Timing of births coincides with abundance of food supply; for example, at the beginning of the monsoon season in northern and central India, and with the calving of Thomson's Gazelle in the Serengeti. Females are typically monoestrous, but there is evidence in Tanzania of multiple litters. Gestation lasts about 63 days. Meanlitter size has been recorded as 5-7 (range 1-8) in Tanzania. In the Bhal area in India average litter size was 3-6 (range 2-5). In Tanzania, two pups on average have been recorded emerging from the den at three weeks of age. Golden Jackals in India excavate their dens in late April to May, mainly in natural and man-made embankments, usually in scrub habitat. Rivulets, gullies, road, and check-dam embankments are prime denning habitats, and drainage pipes and culverts are also used. Dens may have 1-3 openings and typically are about 2-3 m long and 0-5- 1 m deep. In Tanzania both parents and “helpers” (offspring from previous litters) provision and guard the new pups, which results in higher pup survival. The male also feeds his mate during her pregnancy, and both the male and “helpers” (i.e. other social group members) provision the female during the period of lactation.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II ( India). Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. Jackals are on Schedule III of India’s Wildlife Protection Act (1972) and are afforded the least legal protection (mainly to control trade of pelts and tails). However, no hunting of any wildlife is permitted under the current legal system in India. Fairly common throughout its range, although considered to be steadily declining except in protected areas. High densities are observed in areas with abundant food and cover. Known density estimates for parts of India enable a minimum population estimate of over 80,000 Golden Jackals for the Indian sub-continent. Population estimates for Africa are not available, but densities in the Serengeti National Park have been recorded as high as 4 adults /km?®. Traditional land use practices such as livestock rearing and dry farming are conducive to the survival of jackals and other wildlife, but are being steadily replaced by industrialization and intensive agriculture; similarly, wilderness areas and rural landscapes are being rapidly urbanized. Jackal populations adapt to some extent to these changes and may persist for a while, but will eventually disappear from such areas. There are no other known threats, except for local policies of extirpation and poisoning.

Bibliography. Coetzee (1977), Fuller et al. (1989), Genov & Wassiley (1989), Golani & Keller (1975), Golani & Mendelssohn (1971), Jaeger et al. (1996), Jerdon (1874), Jhala & Moehliman (2004), Kingdon (1971-1982), Kruuk (1972), van Lawick & van Lawick-Goodall (1970), Macdonald (1979a), Moehliman (1983, 1986, 1989), Moehlman & Hofer (1997), Mukherjee (1998b), Newton (1985), Poche et al. (1987), Prater (1980), Rosevear (1974), Sankar (1988), Schaller (1967), Sillero-Zubiri (1996), Stanford (1989).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.