Perodicticus potto (Muller, 1766)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6632647 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6632616 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039C9423-FFFA-0875-3460-D7FA57A0FB23 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Perodicticus potto |

| status |

|

West African Potto

Perodicticus potto View in CoL

French: Potto de Bosman / German: Potto / Spanish: Poto occidental

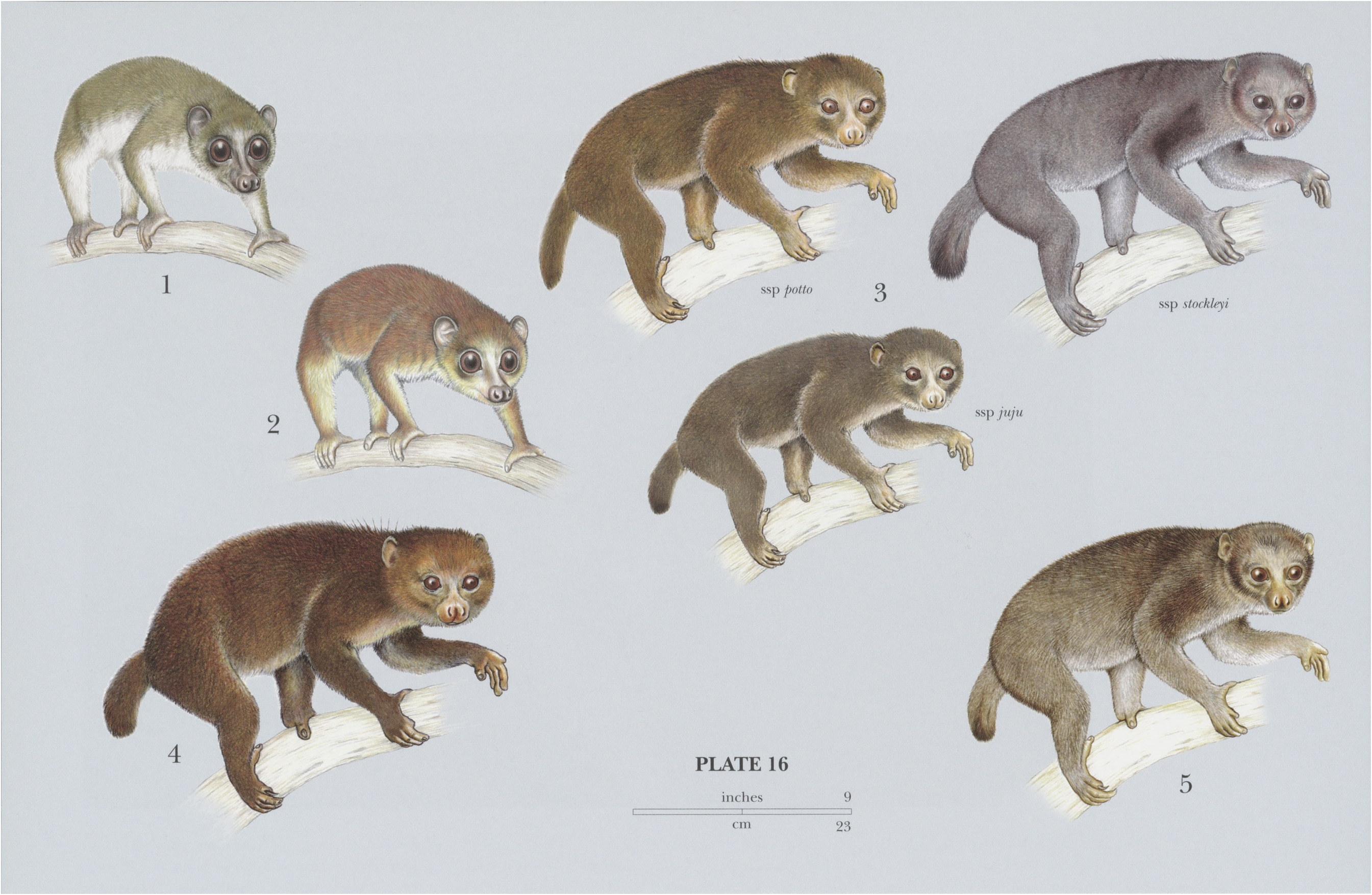

Other common names: Potto, Western Potto; Benin Potto (juju), Bosman'’s Potto (potto), Mount Kenya Potto (stockleyi)

Taxonomy. Lemur potto P. L. S. Miller, 1766 View in CoL ,

Ghana, Elmina.

Data from mtDNA indicated that potto and former subspecies edwards: and ibeanus deserved species designation as shown by C. Roos and coworkers in 2004, a finding supported by marked differences in body size and skull morphology. The form from Benin (juju) is probably also a distinct species, but it is not recognized here. Currently, three subspecies are recognized, but others may well be found in the future.

Subspecies and Distribution.

P.p.jyyuThomas,1910—EbankofVoltaRiverinSEGhanathroughSTogoandSBeninintoSWNigeria.

P. p. stockleyi Butynski & de Jong, 2007 — SW Kenya (Mt Kenya). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body ¢.30 cm, tail 4-6 cm; weight 850-1000 g. The West African Potto is the smallest of the potto species, also notable for its relatively long tail and small teeth. Its body is covered by a coat of dense, dark brown fur, with a dark median stripe and pale hands and feet. Ears are slightly yellowish inside and prominent due to short pelage on the head. Vertebrae are specially adapted to form a nuchal shield. There are long, black, guard hairs (specialized sensory hairs) dorsally from the crown to the scapular region. The “Mount Kenya Potto” (P. p. stockleyi) is quite distinct with a reddish snout; relatively short, creamy, ventral hairs; pale to yellowish brown chin; and cinnamon colored face. Hair on the crown is short (5 mm) and tipped with glossy cinnamon. The shoulder saddle is not very woolly but glossy and strongly tipped with cinnamon; hairs behind the shoulders are tipped with cinnamon and mostly silvery gray.

Habitat. Primary, montane, successional, flooded, riparian, and secondary lowland rainforest. The West African Potto is sometimes found in farms, plantations, and wooded savanna. It commonly moves in the midto upper canopy, 10-20 m or more from the ground. The type specimen of the Mount Kenya Potto was found in montane forest at 1830 m above sea level.

Food and Feeding. There is no specific information for this species, but it probably eats animal prey, fruit, and gum.

Breeding. The West African Potto has one or occasionally two offspring a year. Infants are rarely parked in trees. Data from captivity indicate a gestation of 193-205 days (but the species in captivity are not always known and may be hybrids). Weight at birth is 30-42 g. Weaning occurs at 120-180 days. Young are sexually mature at six months, and young males disperse. Pottos, in general, may live 26 years in captivity.

Activity patterns. The West African Potto is nocturnal, arboreal, and slow-climbing, but it is capable of swift continuous movement. It moves in the canopy at 5-30 m on medium-sized oblique branches. Basal metabolic rate (36-40 kcal/day/kg “7) is about one-half that expected for a mammal of its size. The potto has a larger brain than predicted from its low metabolic rate. When faced with predators, all species of pottos are equipped with three physical adaptations that make them a formidable adversary: a scapular shield produced by a combination of raised apophyseal cervical spines, some of which protrude above the skin in the form of tubercles, covered by thick skin and bristles of sensory hair, that offers protection, defense, and acute sensitivity; muscular hands that allow the potto to firmly grip a substrate without falling off (a potto can support up to 15 times its weight); and the retia mirabilia of the proximal limbs, a dense web of blood vessels that allow stillness for extended periods. The potto first faces a predator uttering a series of grunts, open-mouthed, and butting with the shield. If it fails to dislodge the predator, the potto simply drops to the ground, moves rapidly through the undergrowth and disappears to safety. Low vertebral spines of the thorax may increase flexibility allowing a potto to twist serpentine-like through the canopy. Such movements enable pottos to bridge gaps and search for food while remaining suspended in one spot.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Like other pottos, the West African relies on continuous substrates for movement through the canopy. It has not been studied in detail in the wild. Pottos sleep in dense foliage or clumps with branches or forks and do not build nests. Densities range from 4-7 ind/km* on Mount Kupe in Cameroon to 810 ind/km? in north-eastern Gabon.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red List. The subspecies potto is also classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List, and the subspecies stockleyi is classified as Data Deficient; it is known only from a single specimen in the Kenya National Museum, Nairobi, and efforts through interviews and field surveys to locate a surviving wild population have been unsuccessful, which means it may be extinct. The subspecies juju (the “Benin Potto”) is not listed on The IUCN Red List, and its conservation status has not been assessed. The nominate subspecies occurs in a number of protected areas: the national parks of Bia, Kakum, and Kyabobo in Ghana; Tai National Park and Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve in the Ivory Coast; Sapo National Park in Liberia; Okomu National Park in Nigeria; Tiwali Island Wildlife Sanctuary in Sierra Leone; and Niokolo Koba National Park in Senegal. Overall, West African Pottos are widespread and common.

Bibliography. Bearder & Pitts (1987), Bearder et al. (2003), Bender & Chu (1963), Buckanoff et al. (2006), Butler & Juma (1970), Butynski & de Jong (2007), Charles-Dominique (1977a), Cowgill (1969, 1974), Cowgill et al. (1989), Frederick (1998), Frederick & Fernandes (1994, 1996), Gosling (1982), Grand et al. (1964a, 1964b), Groves (2001), Grubb (1978), Grubb et al. (2003), Heffner & Masterton (1970), Hildwein & Goffart (1975), Hill (1953d), Ioannou (1966), Jenkins (1987), Jewell & Oates (1969a, 1969b), Jouffroy et al. (1983), Kingdon (1971), Manley (1966), McGrew et al. (1978), Montagna & Ellis (1959), Montagna & Yun Jeung-Soon (1962b), Napier & Napier (1967), Oates (1984, 2011), Petter & Petter-Rousseaux (1979), Pollock (1986d), Ravosa (2007), Roos et al. (2004), Rumpler et al. (1987), Schwartz & Beutel (1995), Schwarz (1931b), Suckling et al. (1969), Walker (1968a, 1968b, 1969, 1970).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.