Nycticebus pygmaeus, Bonhote, 1907

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6632647 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6632687 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039C9423-FFF2-087C-3176-DC5B5E3FF2DC |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Nycticebus pygmaeus |

| status |

|

Pygmy Slow Loris

Nycticebus pygmaeus View in CoL

French: Loris pygmée / German: Kleiner Plumplori / Spanish: Loris perezoso pigmeo

Other common names: Lesser Slow Loris, Pygmy Loris

Taxonomy. Nycticebus pygmaeus Bonhote, 1907 View in CoL ,

Nha-trang, Annam (= Vietnam).

Coat color does not change throughout the range. Although sympatric with N. bengalensis , there is no evidence of hybridization between the two. Monotypic.

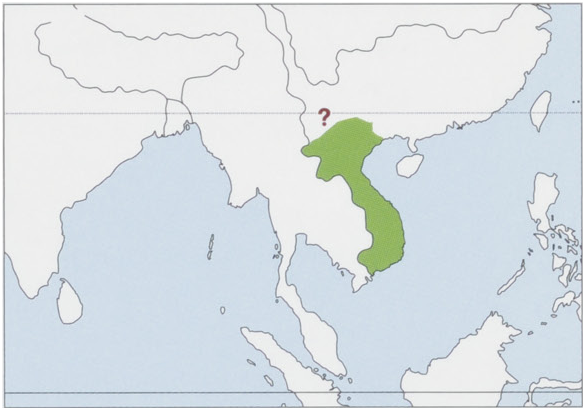

Distribution. Laos, Vietnam, and E Cambodia (E of the Mekong River), the precise W limit of the distribution is uncertain, but it appears to be absent (or at least very scarce) in the extreme W of the Mekong plain; records from S China (SE Yunnan Province) are uncertain and may be based merely on released captives brought in from elsewhere. View Figure

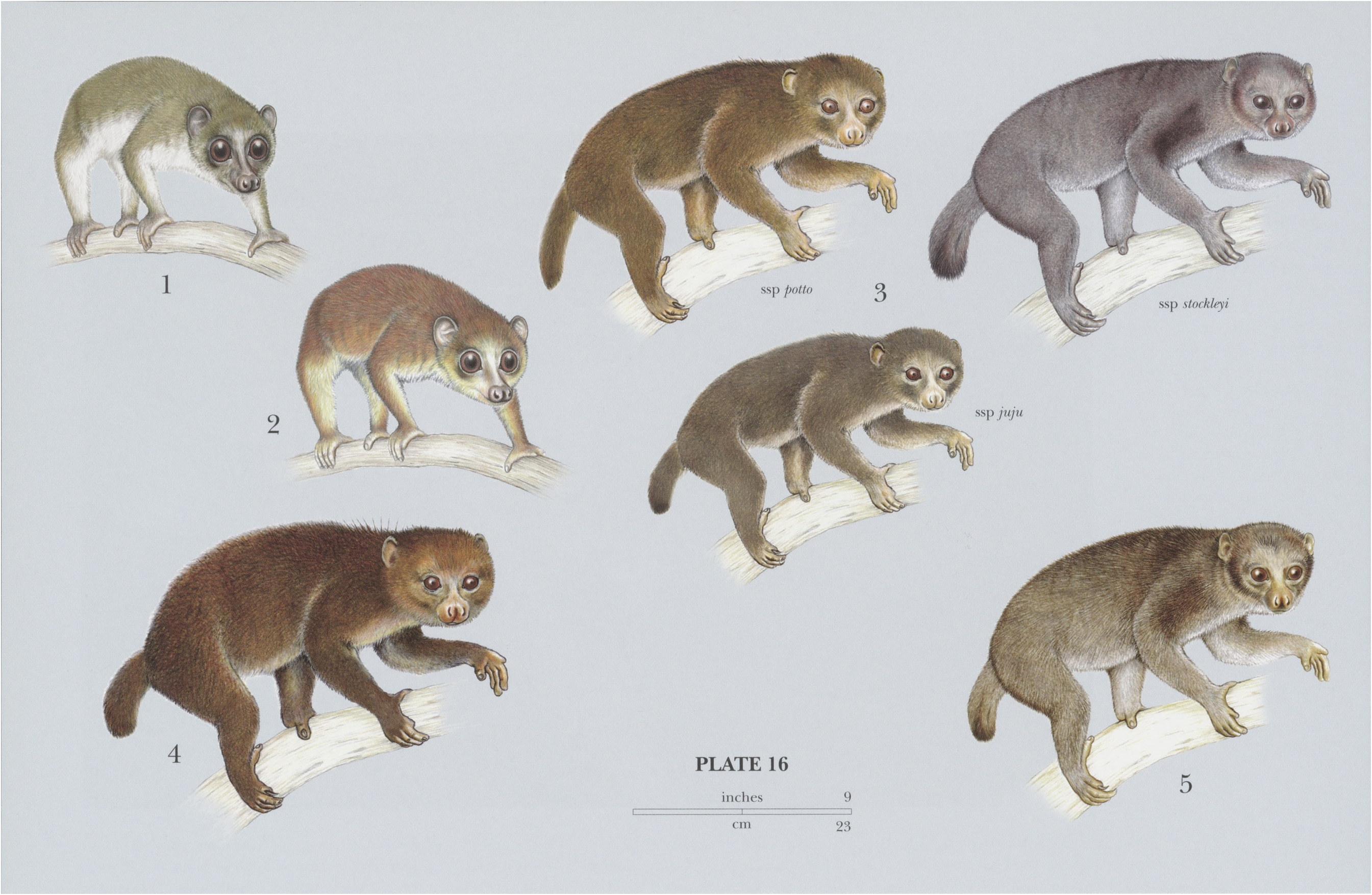

Descriptive notes. Head—body 20-23 cm (males) and 19.5-23 cm (females), tail 1-8 cm; weight ¢.420 g (males) and c.428 g (females). Although quite similar to the other members of its genus in overall appearance, the Pygmy Slow Loris is smaller and has a pointed snout with a black nose. The fur is finely textured, and there is considerable age-related and seasonal difference in coloration. In summer,it is reddish buff to orange above and whitish below, with a broad but indistinct brown dorsal stripe. The winter coat is much thicker and darker, with a dark-brown to black dorsalstripe, silver frosting, and a whitish-brown underside. Head forks are brown in summer and darker brown in winter. Body size nearly doubles in winter in some parts its range. Ears are long, black, and leathery. There is a white rectangular interocular stripe.

Habitat. Primary and secondary evergreen forest, rainforest, karst forest, and bamboo thickets. The Pygmy Slow Loris can survive in highly degraded habitats. Flowering trees are most attractive to these animals.

Food and Feeding. The Pygmy Slow Loris is a faunivore-frugivore and specialized gum feeder. Consumption of saps and gums is similar to other lorises, and it is described here in detail for illustration. Pygmy Slow Lorises consume sap and gum from as low as 1 m to as high as 12 m off the ground. They perforate the superficial layer of the cambium of trees or lianas by scraping with their toothcomb. Lapping exposed sap with the tongue lasts from a few seconds to about four minutes, with intermittent additional breaking of the hard surface. Gum is consumed for a longer period, from two to 20 minutes, and involves gouging with anterior teeth. In most cases,trees already have wounds from larval infestation, prior injury, orfire, although lorises can also gouge into undamaged wood to induce gum flow. Lorises scoop up the gum, anchoring their upper incisors into the bark or into the solidified gum. In this manner, Pygmy Slow Lorises can also gouge into bamboo to find insects, and they appear to scrape lichens and fungus off the surface of old bamboo with their toothcomb. Until recently, no species of loris has been observed to gouge gum with its molars. Pygmy Slow Lorises in Cambodia eat “icicles” of gum exuded from open wounds, and while holding them in one hand, they alternately chew on them with their molars and lick them. Lorises search for their gum sources. Nosedown searching may accompany investigating for sap on branches, or searching along bamboo to find a location to gouge for insects. Visible and audible sniffing sometimes accompanies these searches. On gum trees without active wounds, Pygmy Slow Lorises race up and down a single trunk, making up to 20 trial holes before feeding. Trees with open wounds seem to be known to individual lorises; they make rapid and directed movement to a feeding site. When gouging begins, bark breaking can be audible to humans from a distance of 10 m. A loris may turn its head side to side while spitting out bits of bark; this side-to-side movementis often accompanied by scent marking of the wound with facial glands. Pymgy Slow Lorises consume bits of bark in this process. The more noisy process of gouging bamboo involves a loris anchoring its rear feet against the bamboo and bashing its toothcomb into the very hard surface; this behavior also results in shaking of the bamboo stand and is audible up to 100 m away. Pygmy Slow Lorises also eat flowers, geckos, small fruits, nectar, and numerous invertebrate prey.

Breeding. Females reach maturity at 14 months of age and give birth at 19-37 months; malesfirst reproduce at 27-37 months. Adult males have a large testis volume. Estrus lasts 6-11 days. Gestation is 187-198 days. In the wild, Pygmy Slow Lorises give birth to twins that are carried for their first two to three weeks, after which the mother tends to park them while she forages She moves them to a new spotif she senses that they will be disturbed. Infant mortality is high. Infants are almost weaned within 24 weeks. In captivity, the interbirth interval is 13-30 months.

Activity patterns. The Pygmy Slow Loris is nocturnal and arboreal. This supposedly slow climber moves rapidly on small branches from the ground to the highest point in the canopy. It makes use of long bamboo connectors to move across the arboreal pathway. During a radio-tracking study in Cambodia, the activity pattern of the Pygmy Slow Loris was 27% traveling, 22% alert, 20% sleeping, 5% feeding, 3% autogrooming, and 6% diverse, less common, behaviors; 17% of the records were unknown activities. Pygmy Slow Lorises only increased activity on bright moonlit nights as ambient temperatures increased, yet they were consistently active regardless of temperature on dark nights. The most plausible explanation for these patterns is the combined risk of predation (as a result of their anti-predator strategy) and heat loss on cool bright nights resulting in lunar phobic behaviors.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. In Cambodia, the Pygmy Slow Loris showed a dispersed multimale-multifemale social organization. Home ranges were c.22 ha for adult males and c.12 ha for adult females. Males had variable but large home ranges and long nightly travel distances compared with adult females. Animals slept alone 96% of the time; sleeping sites were located in thick vegetation high in the canopy. Adult males rarely returned to the same sleeping sites, which were along the perimeter of their home range. Adult females showed fidelity to their sleeping sites, which were located closer to the center of home ranges. Individuals groomed one another, fed together, and called to each other. Reintroduced Pygmy Slow Lorises in Vietnam also slept together.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. The Pygmy Slow Loris is legally protected in China, Vietnam, and Cambodia. Nevertheless,it is still heavily exploited for use in traditional Asian medicine and the pet trade, and it is occasionally eaten. As a result, the overall population has likely declined by 30% over the past 24 years. In Cambodia, large numbers of dried lorises, more Pygmy than Bengal slow lorises, can be seen in markets, where they are sold in the belief that preparations made with them are, for example, a tonic for women after childbirth and helpful for stomach problems, treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, and useful for healing wounds. Beliefs in their curative powers are strong, and people are reluctant to accept alternative medicines. Habitat loss is also a threat, mainly due to agriculture. Wild populations of the Pygmy Slow Loris appear to be in major decline, but it does occur in numerous protected areas in Cambodia, China, Laos, and Vietnam. Detailed surveys of the status of the Pygmy Slow Loris in these areas is needed. It also occurs in at least 50 captive collections.

Bibliography. Alterman & Hale (1991), Dao Van Tien (1960), Duckworth (1994), Fisher et al. (2003a, 2003b), Fitch-Snyder & Ehrlich (2003), Fitch-Snyder & Jurke (2003), Fitch-Snyder & Schulze (2001), Fitch-Snyder & Vu Ngoc Thanh (2002), Fitch-Snyderet al. (2008), Groves (2001), Hagey et al. (2007), Jurke et al. (1997), Munds et al. (2008), Nekaris & Munds (2010), Nekaris & Nijman (2007b), Nekaris, Collins et al. (2010), Nekaris, Shepherd et al. (2010), Ratajszczak (1998), Sodaro (1993), Starr, Nekaris et al. (2010, 2011), Starr, Streicher et al. (2008), Streicher (2003, 2004, 2007), Tan & Drake (2001), Zhang et al. (1987).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.