Corymorpha tropica, Galea, 2023

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.5254.4.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:12BEFF3B-8EC8-436B-B813-8710539107AF |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7733873 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039B9453-1D1D-FFD3-D2C0-FAB45DB2A892 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Corymorpha tropica |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Corymorpha tropica View in CoL , sp. nov.

Figs 1–9 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 View FIGURE 7 View FIGURE 8 View FIGURE 9 , Tables 1–2 View TABLE 1 View TABLE 2

Corymorpha tomoensis View in CoL — Vervoort, 2009: 760, figs 1–2 (non Corymorpha tomoensis Ikeda, 1910: 153 View in CoL , pl. 5).

Material examined. Holotype: MSNMCoe357, Indonesia, Bali, Amed , dive site known as “Ghost Bay”, -8.332965°, 115.643044°, 5–15 m, 04 Oct 2022, a 3 cm high, fertile polyp and numerous newly-released medusae . Paratypes: MSNMCoe358, same location data as the holotype, 5–15 m, 04 Oct 2022, a fertile polyp, 2 cm high.—MSNMCoe359, same location data as for the holotype, 10–20 m, 07 Oct 2022, a ca. 3 cm high, fertile polyp and numerous newlyreleased medusae.—MSNMCoe360, same location data as for the holotype, 10–20 m, 07 Oct 2022, a ca. 2 cm high, fertile polyp and several newly-released medusae . Additional material: MHNG-INVE-0137170, Indonesia, Bali, Tulamben , dive site known as “Melasti”, -8.291824°, 115.609316°, 20 m, 30 Jan 2020, a colony composed of several large polyps to 2.5 cm high, as well as many smaller offspring, and newly-released medusae .

Etymology. From the Latin trŏpĭcus, -a, -um, meaning tropical, to designate its ecological affinities.

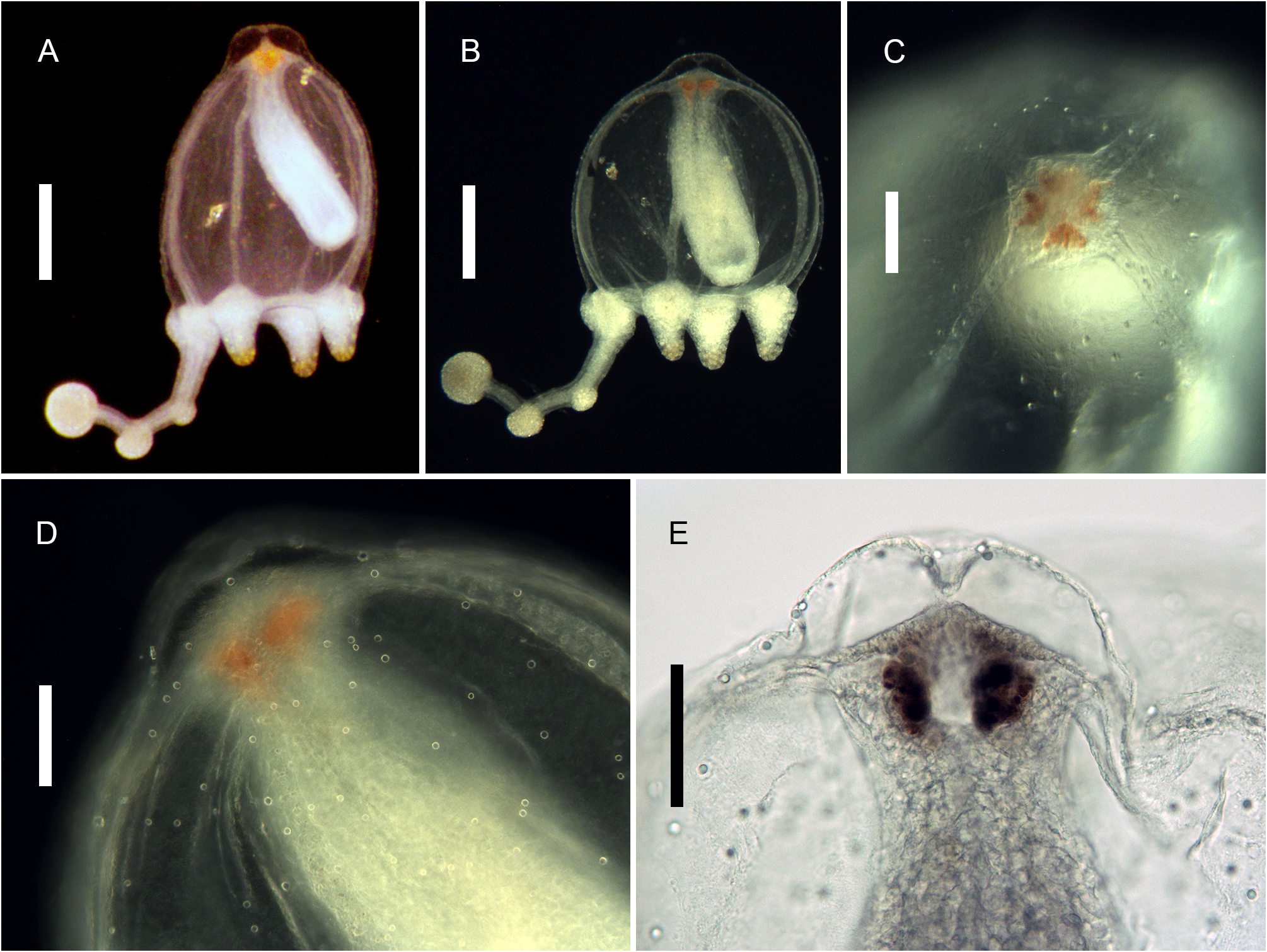

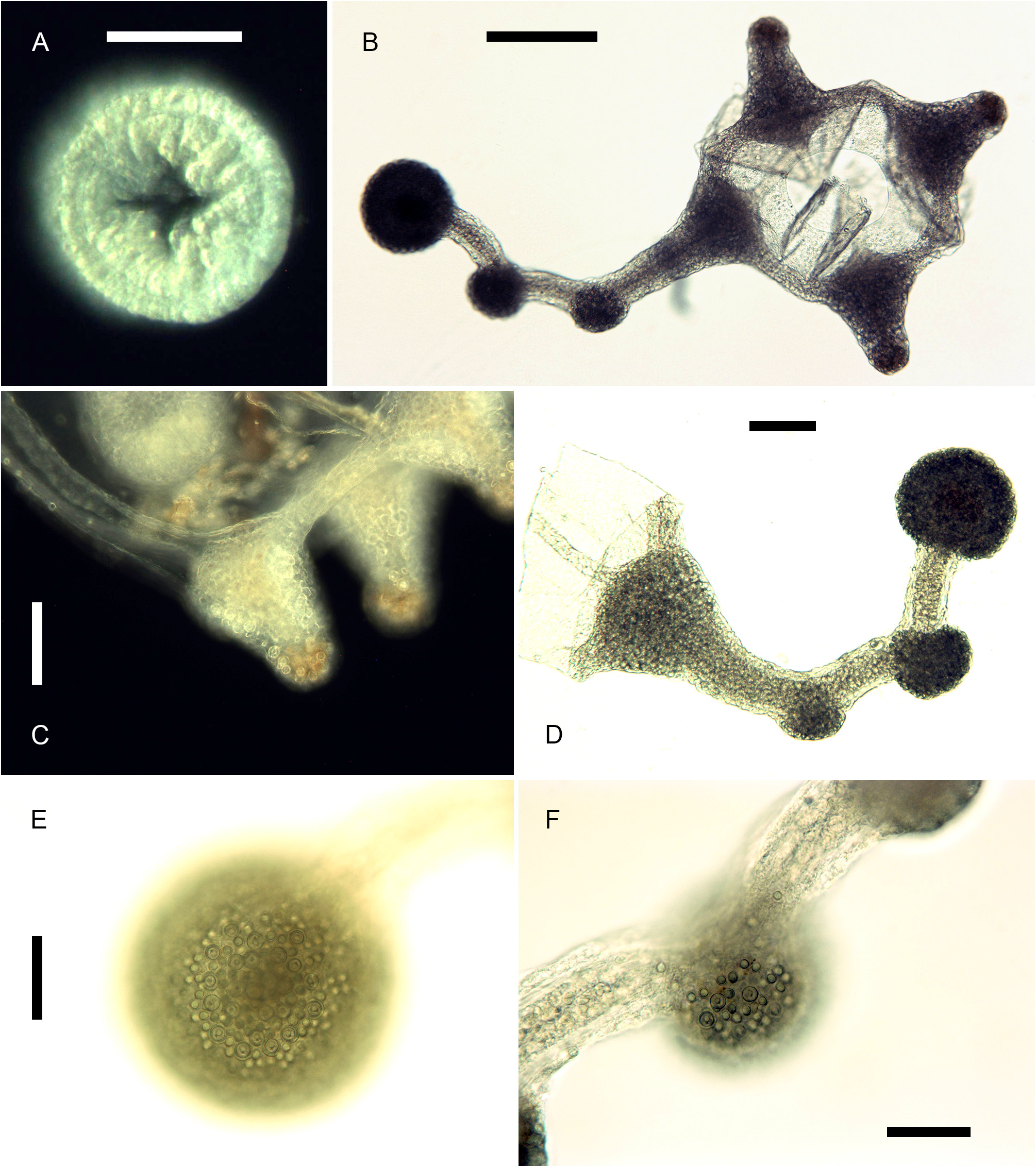

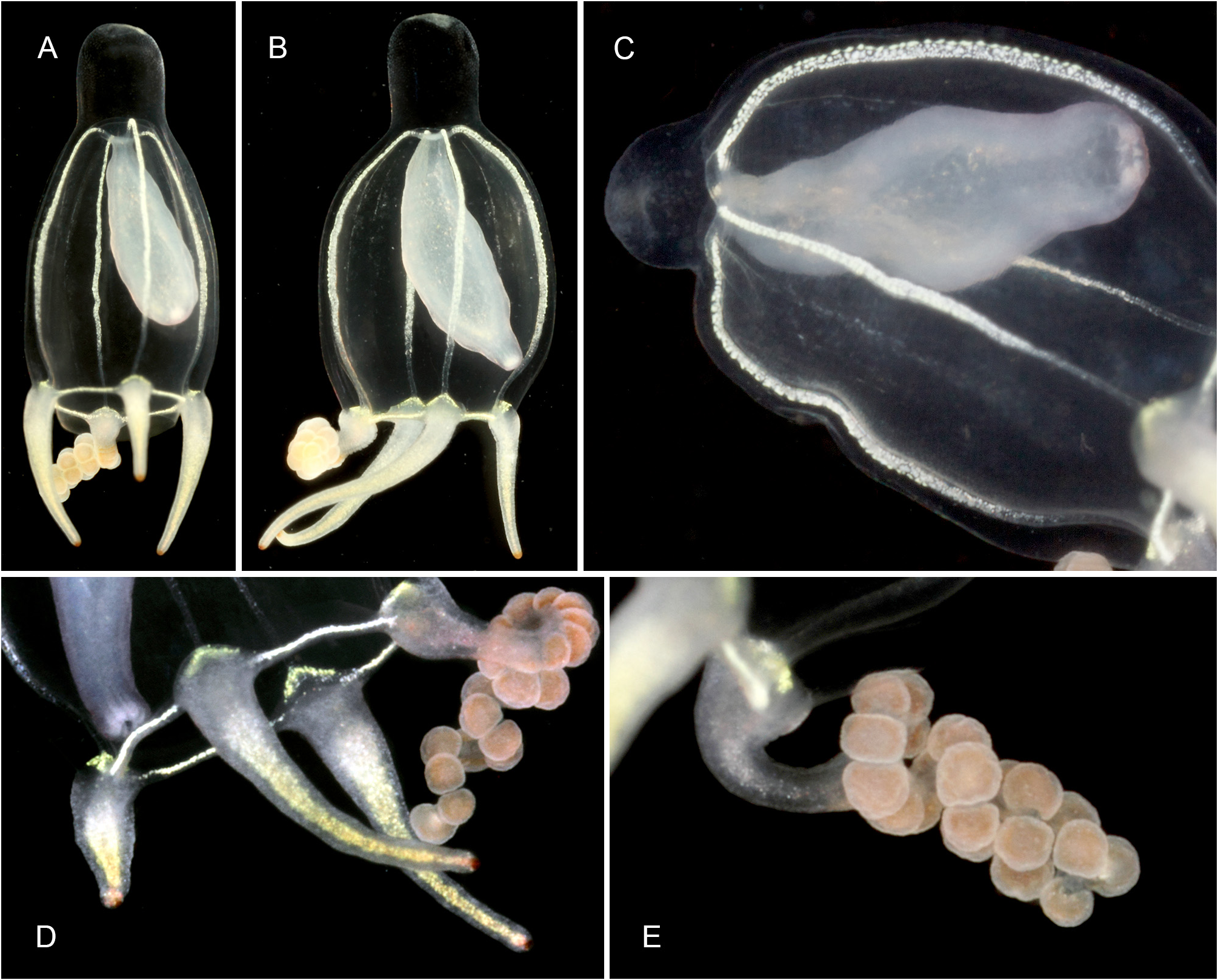

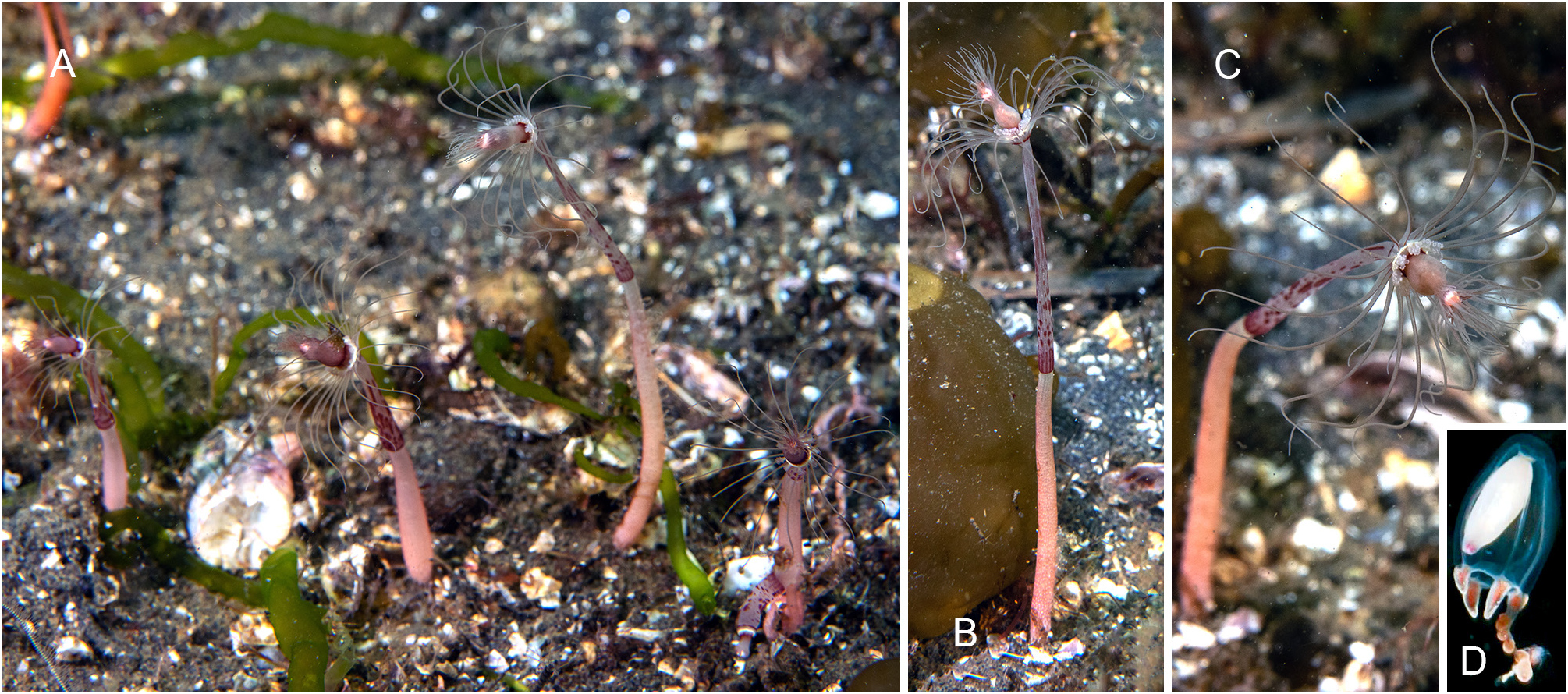

Description. Polyps occurring exclusively on sandy bottoms; either solitary or forming small colonies composed of a few, large individuals surrounded basally by many smaller offspring; up to 3 cm high in studied material; composed of a large hydranth atop a long hydrocaulus. The latter almost isodiametric throughout when the polyp is fully extended, up to 1.5 mm wide, distinctly divided into two parts of roughly comparable length: a proximal, perisarc-covered one, and a distal, naked one; tip of proximal part conical, ca. 3 mm long, giving rise laterally to numerous, long (ca. 5 mm), slender, almost transparent, adhering filaments anchoring the polyp in sand; above, surface with a varied number of digitiform, pendulous papillae, rapidly decreasing in length up the stem and there appearing as mere, ovoid blotches; papillae originating at the ends of short, lateral diverticuli, arranged either alternately or in opposite pairs along up to a dozen peripheral, straight, longitudinal canals traversing the caulus from one end to the other; perisarc thin, transparent, not adhering to the coenosarc, ending abruptly at junction between the proximal and distal parts of caulus; distal part, immediately above junction, with a noticeable concentration of nematocysts (large, spherical capsules, as in the medusa, and type S 2 stenoteles; see below); longitudinal canals in this part of the caulus devoid of diverticuli, but occasionally branched, the branches sometimes fusing again a short distance further up; core of caulus filled with large, polygonal, parenchyme cells, leaving but a central, narrow lumen; very distal end of caulus with a distinct constriction at junction with the base of the hydranth. The latter flask-shaped, ca. 5–7 mm long and 1.5 mm wide basally; divided internally by a transverse septum into a lower, shallow, non-digestive part, filled with parenchyme cells, and a much taller, upper, hollow, digestive part; a whorl of 23–38 aboral tentacles at the base of the polyp, and 28–44 oral tentacles surrounding distally the hypostome; aboral tentacles arranged in a single whorl, arching gracefully outwards, up to 1 cm long, solid (core filled with parenchyme cells), laterally flattened, gradually tapering distally, with clusters of nematocysts smoothly spread on both the upper and lower surfaces, but not laterally (pseudofiliform type); oral tentacles tightly bunched, arranged in 4 decussate whorls, slightly arching outwards, up to 2 mm long, solid, with very elongated bases, becoming circular in cross section above, surface rough, vaguely transversely “annulated”, due to the presence of almost circular clusters of nematocysts, although not forming distinct capitations; hypostome dome-shaped, ca. 1 mm long. Up to 16 blastostyles arise in a whorl a short distance above the aboral tentacles; tubular, 4–5 mm long in a relaxed state; main axis giving rise irregularly along its length to 6–7 short, lateral branches bearing at their distal ends dense clusters of medusa buds at various stages of development. Most developed buds, as well as newly-released medusae, bell-shaped, higher than wide (765–945 µm vs. 630–720 µm), umbrella circular in cross section, margin slightly oblique in lateral view, exumbrella smooth-walled, surface with scattered, small, spherical nematocysts; a moderately-developed, dome-shaped, apical process traversed by a short apical canal; mesoglea thin; manubrium club-shaped (630–765 µm long, 190–200 µm wide), not exceeding the height of subumbrella, lumen cross-shaped in transverse section, mouth equally cross-shaped, provided with small stenoteles (type S 4; see below); 4 radial canals ending distally in a circular canal; 3 short (200–225 µm), conical, tentacle bulbs, and a single, well-developed (630– 720 µm long), hollow tentacle provided with 1–2 hemispherical (90–125 µm wide), adaxially-placed nematocysts clusters, as well as a much larger, globular (160–180 µm wide), distal cluster (tentacle of semimoniliform type); velum closing the subumbrella as a stretched diaphragm; there are no sense organs; no gonads were produced around the manubrium at this stage.

Color of living specimens: polyp—lower (perisarc-covered) part of the caulus variously-colored, from (rarely) almost translucent (allowing to see by transparency a white, granular matter inside the endodermal canals), to (commonly) light brown-colored, to orange (in the two latter cases, the endodermal canals are mostly obscured by the general dark tinge of the coenosarc); papillae white; upper (naked) part of the caulus of varied colors, from translucent with occasional brick-red spots or irregular, longitudinal bands (endodermal canals, seen by transparency, white), to entirely brick-red (longitudinal canals mostly obscured); hydranth base with a distinctlydemarcated to diffuse, more or less wide, brick-red, circular band; upper body part of varied colors, from nearly white to intense brick-red or orange; adaxial side of aboral tentacles intense brick-red, color fading away abruptly on the lateral sides, to become almost white on their abaxial side; outer surface of oral tentacles from brick-red to transparent, cores white; in some rare, depigmented individuals, all tentacles and the hydranth body are translucent. Medusa—mesoglea transparent; radial and circular canals with white pigment granules; there are four interradial brick-red spots at the insertion of the otherwise entirely translucent-white manubrium; the generally contracted mouth is discernible as a white cross; bases of all tentacles translucent-white; tips of atentaculate bulbs brick-red; main tentacle with an intense white, endodermal core; intermediate clusters of nematocysts translucent-white; distal cluster translucent on surface, but having a brick-red core.

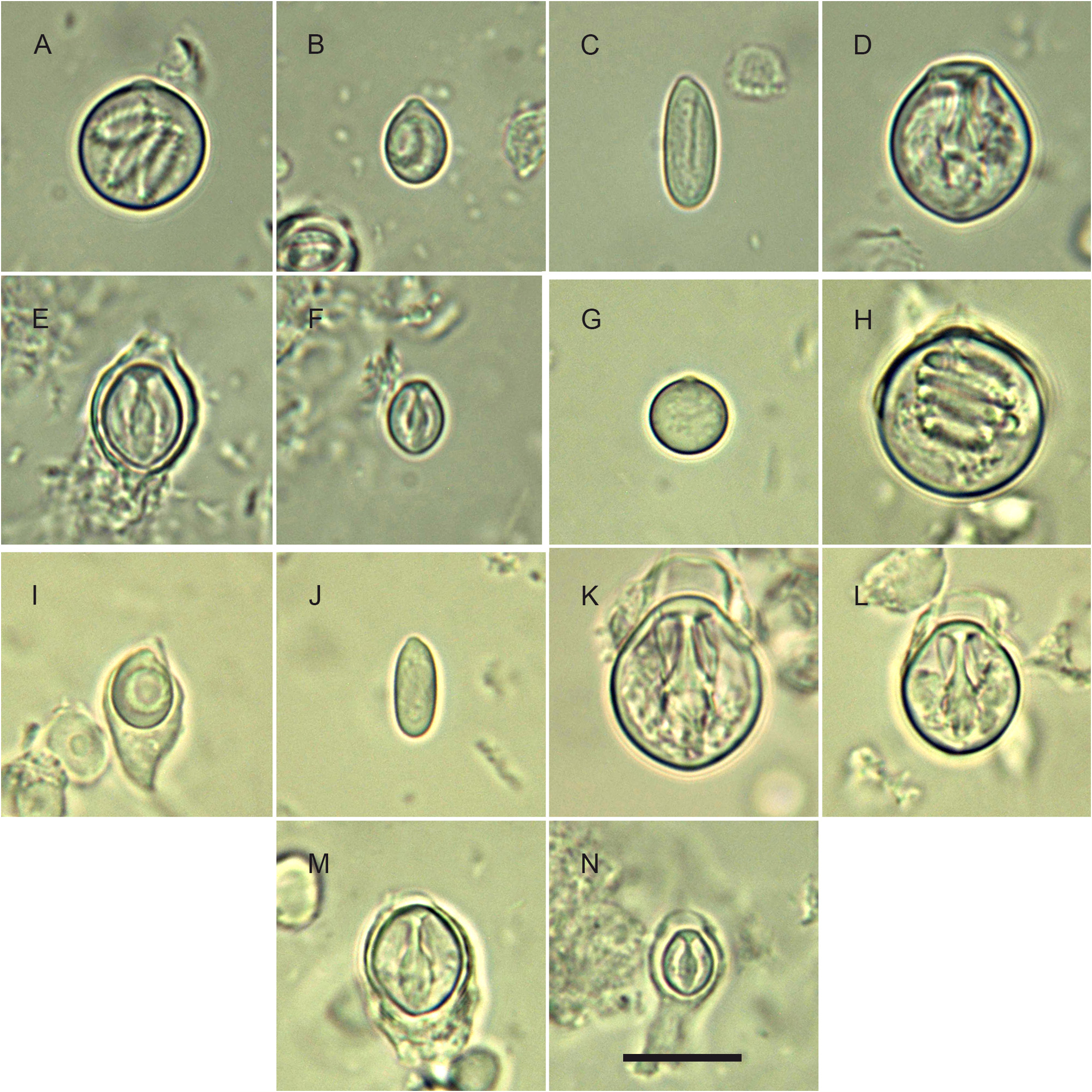

Cnidome: its composition is summarized in Table 1 View TABLE 1 and illustrated in Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 . There are 4 size classes of stenoteles (designated here as S 1, S 2, S 3 and S 4); type S 2 does not occur in the polyp stage. Except for some discharged stenoteles and desmonemes, all the remaining capsules were seen undischarged, and their assignation to a given type was not attempted until new, reliable observations on living material are made.

Remarks. Many small offspring have been observed around the bases of some large polyps (e.g., Fig. 1A View FIGURE 1 and MHNG-INVE-0137170), but their relationships were not studied in detail. A similar situation is known to occur in other congeners, e.g., C. nutans M. Sars, 1835 , C. rubicincta Watson, 2008 (original account), C. tomoensis Ikeda, 1910 (original account). In the former, Rees (1957: 485–486, fig. 35) was able to demonstrate that this was the result of frustulation from the tips of the anchoring filaments. Conversely, Watson (2008: 188) speculated that “fertilized ova may drop from the [fixed] gonophore [of C. rubicincta ] directly to the substrate to commence growth as new hydrocauli”, but this seems unlikely, considering the more plausible observations made by Rees.

I have no doubts that the Indonesian material assigned by Vervoort (2009: 760) to C. tomoensis Ikeda, 1910 , a species only known from Japan, is conspecific with the present species. It has the same appearance as the specimens collected and studied by myself, and the distinctive boundary between the proximal and distal parts of the caulus is still visible in the preserved specimen shown in his Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 .

Medusae of C. tropica were abundantly produced, and easily and massively liberated in a short interval (not exceeding an hour) between the sampling of fertile polyps and their fixation. They have a main tentacle provided distally with a large, spherical nematocyst knob, as well as with 1–2 additional, smaller, intermediate clusters along its adaxial side. Since no gonads were developed around the manubrium at this stage, it is assumed that the medusa is relatively long-lived and undergoes further development, with its main tentacle expected to add more intermediate nematocyst clusters as it lengthens, and the 3 others possibly being able to develop further, as well (some medusae have longer bulbs compared to others). Nevertheless, the presence of two adaxial, intermediate knobs on the main tentacle is an essential feature that helps distinguish the new species from its congeners.

Indeed, most of them are exclusively known through their planktonic stage (a complete set of characters is tabulated in Appendix 1). The following species could be confidently excluded on different grounds:

1) their medusae have a main tentacle with abaxially-placed nematocyst clusters— C. abaxialis ( Kramp, 1962) , C. apiciloculifera ( Xu & Huang, 2003) , C. brunnescentis ( Huang, 1999) , C. gemmifera ( Bouillon, 1978b) , C. interogona ( Xu & Huang, 2003) , C. knides ( Huang, 1999) , C. macrobulbus ( Xu & Huang, 2003) , C. multiknoba ( Xu, Huang & Guo, 2014) , C. pileiformis ( Xu, Huang & Guo, 2014) , C. pseudoabaxialis ( Bouillon, 1978b) , C. vacuola (Xu, Huang & Guo, 2012) and C. verrucosa ( Bouillon, 1978b) ;

2) their medusae have a main tentacle of moniliform type — C. annulata ( Kramp, 1928) , C. bitungensis (Xu, Huang & Guo, 2013) , C. floridana Schuchert & Collins, 2021 , C. fujianensis ( Xu & Huang, 2006) , C. gracilis ( Brooks, 1883) , C. juliephillipsi ( Gershwin, Zeidler & Davie, 2010) , C. nana Alder, 1857 , C. nanhaiesis ( Huang, Xu & Lin, 2012) , C. nutans M. Sars, 1835 , C. russelli ( Hamond, 1974) , C. solidonema ( Huang, 1999) and C. taiwanensis ( Xu & Huang, 2003) ;

3) their medusae have a variously-shaped main tentacle that has neither ab- or adaxially-placed nematocysts clusters, nor a moniliform arrangement— C. cargoi (Vargas-Hernández & Ochoa-Figueroa, 1991) , C. forbesii ( Mayer, 1894) , C. furcata ( Kramp, 1948) , C. gigantea ( Kramp, 1957) , C. intergona ( Huang, Xu & Guo, 2012) , C. normani ( Browne, 1916) , C. similis ( Kramp, 1959) , C. typica ( Uchida, 1927) and C. valdiviae ( Vanhöffen, 1911) ;

4) all medusa tentacles are alike, with no differentiated main tentacle— C. januarii Steenstrup, 1855 ;

5) there are no free-living medusae, but fixed gonophores of various types — C. anthoformis ( Yamada, 1977) , C. glacialis M. Sars, 1860 , C. groenlandica ( Allman, 1876) , C. microrhiza ( Hickson & Gravely, 1907) , C. palma Torrey, 1902 , C. parvula ( Hickson & Gravely, 1907) , C. pendula L. Agassiz, 1862 , C. rubicincta Watson, 2008 , C. sarsii Steenstrup, 1855 and C. uvularis ( Fraser, 1941) ;

6) their ecology is peculiar for the genus— C. balssi Stechow, 1932 .

Another congener, C. symmetrica Hargitt, 1924 , is also rejected because it is thought to belong to the genus Ralpharia Watson, 1980 (see Appendix 1).

Besides the nominal species listed above, there are four congeners whose medusae possess adaxially-placed nematocyst clusters, similarly to C. tropica , but there are several characters allowing a specific separation:

1) C. bigelowi ( Maas, 1905) —one might justifiably wonder whether this morphologically-similar medusa ( Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ), mainly known from the Indo-Malayan region ( Kramp 1968), could be the mature growth form of the newly-released medusae produced by the present hydroid. Petersen (1990: 150, fig. 17A) provided a good illustration of a C. bigelowi medusa from Laing Island belonging to Bouillon’s collection, and it perfectly agrees to the established concept of this species ( Maas 1905, 1906; Vanhöffen 1913; Kramp 1928, 1961). It could be reasonably assumed that Bouillon (1978b: 262), based on similar specimens from the same locality, gave the correct cnidome composition for the medusa of this species. One of the most salient differences with C. tropica relies in the absence of scattered nematocysts on the exumbrella, while they are unmistakable in the new species. Bouillon (1978b), supplementing an earlier report ( Bouillon 1978a), did not mention exumbrellar nematocysts, while their presence was noted in two other congeners (viz. C. gemmifera and C. pseudoabaxialis ) described in the same work. Consequently, it is deduced that no such capsules are present in C. bigelowi 1,2. Additional distinguishing features are summarized in Table 2 View TABLE 2 . In brief, unlike in my material, only two size classes of stenoteles are mentioned by Bouillon (1978b) in C. bigelowi : large [probably corresponding to type S 1 dealt with herein ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 , Fig. 9K View FIGURE 9 )] and small [probably corresponding to type S 3 dealt with herein ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 , Fig. 9M View FIGURE 9 )]; the former is absent from the main tentacles of my medusae. His desmonemes agree in size with those present in my medusae, but they are said to occur in both the capitate and non-capitate tentacles, while they are only present in the main tentacle of my medusae. His spherical basitrichous capsules, reportedly similar to those met with in C. forbesii (and illustrated in his fig. 8-3), are possibly of the same type as the large, spherical, as yet unidentified nematocysts occurring in my material ( Fig. 9H View FIGURE 9 ), although they are comparatively larger. The heterotrichous microbasic euryteles occurring in all tentacles of C. bigelowi have a possible equivalent with a similar elliptical shape in C. tropica (a thread with a well-defined shaft is visible in the undischarged capsules), but the capsules of the latter are about half their size. Capsules similar to the oval atrichous nematocysts reported upon by Bouillon were not seen in C. tropica , in spite of the careful examination of multiple cnidome preparations. Moreover, it should be also highlighted that the cnidome composition given by Bouillon (1978b) differs from that provided by Sassaman & Rees (1978: 492) for medusa specimens originating from Monterey Bay, CA, USA (see Table 2 View TABLE 2 ), suggesting that two morphologically-similar species could be involved. In this case, too, my Balinese medusae differ significantly from those from the eastern Pacific {e.g., one and three types of nematocysts, respectively, are present on the exumbrella; the main tentacle of the newly-released medusae obtained by Sassaman & Rees had “a club-shaped terminal nematocyst bulb, but [was] lacking the subterminal adaxial bulbs of older medusae” (see their figs 1B and 2C–D)}. As to the cultivated polyp, it has proved to be morphologically different from those of C. tropica (it is proportionally smaller, bears lesser tentacles in each of the two whorls, the perisarc covers entirely the caulus, the hydranth is comparatively more elongated, and there is no mention of a possible striking coloration in live material). Finally, the invariablypresent, conspicuous, red-brick spots at the insertion of the manubrium in the live medusae of C. tropica ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ) were never mentioned in any of the numerous accounts on C. bigelowi , nor are they discernible in the medusa illustrated in Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ;

2 View FIGURE 2 ) C. crassocanalis ( Xu & Huang, 2003) —this medusa, known from the Taiwan Strait (ca. 22– 23° N), has “broad” radial canals, filled with groups of “vacuolated endodermal cells” ( Xu & Huang 2003: 137–138, 143), while those of C. tropica are narrow and composed of flattened, non-vacuolated cells;

3) C. luoyuanensis (Xu, Huang & Yang, 2022) —this medusa, discovered in the Luoyuan Bay , China (ca. 26° N), has a funnel-shaped manubrium extending beyond the velar aperture, broad radial canals filled with apparently large, “vacuolated endodermal cells”, and its main tentacle is reportedly said thick, rigid (inextensible?), and of a compact appearance, the nematocyst clusters being adjacent to one another ( Liu et al. 2022: 346) (if the condition of the main tentacle is not an artefact, it could be diagnostic); in contrast, as noted above, the radial canals of C. tropica are narrow; additionally, its main tentacle is thin, extensible, and the clusters of nematocysts are well separated from one another;

1 Uchida (1927: 189), however, observed in specimens from Japan (ca. 34° N) that “the exumbrella is finely granulated with nematocysts, especially in the terminal portion”, suggesting that his specimens could belong to another, morphologicallysimilar species. He even suspected that these medusae could be the planktonic stage of C. tomoensis Ikeda, 1910 ( Uchida 1927: 190–191). Newly-released medusae were originally lost from the type material of the latter, but “[s]ome old medusae still in attachment have […] somewhat moniliform tentacles” ( Ikeda 1910: 155), a statement not clearly supported by the illustration provided on pl. 5 fig. 2 in the original account (indeed, the main tentacle is provided but with only a distal knob of nematocysts, and no intermediate clusters are distinctly discernible).

2 It is unclear whether the presence of exumbrellar nematocysts is an ontogenically-stable character in the new species in particular, and within the genus in general. For example, in some zancleid hydroids, the presence of such capsules was reported in newly-released medusae, but they appear to be lost in fully-grown individuals ( Boero et al. 2000). Conversely, as noted above, mature medusae of C. gemmifera and C. pseudoabaxialis do have exumbrellar nematocysts.

4) C. meijiensis (Xu, Huang & Guo, 2013) —this medusa, known from the Mischief Reef, Spratly Islands (ca. 9° N), has a broad manubrium filling almost the whole subumbrella (artefact due to the presence of food items, or the thickness of the gonadal mass surrounding it?), the main tentacle is “short and stiff” (inextensible?), with adjacent nematocyst clusters, the opposite tentacle is of the same length and has a red-pigmented tip, while two lateral bulbs are atentaculate ( Du et al. 2013: 749; Liu et al. 2022: 347); in contrast, the manubrium of the newly-released medusae of C. tropica is slender, and its main tentacle is thin, extensible, with well-spaced nematocyst clusters.

The coloration pattern met with in the polyp of C. tropica recalls that displayed by two other congeners, namely C. rubicincta Watson, 2008 and C. tomoensis Ikeda, 1910 (differences to the latter are discussed below in a specific paragraph). As to C. rubicinta ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 ), it could be distinguished from the new species through the following features:

1) the lower part of its caulus is yellow, sometimes reddish, especially proximally, the color “gradually fading distally to primary band”; the hydranth body is pale flesh-colored, with “usually a band of red spots just above aboral tentacles and similar spots on bases of inner row of oral tentacles”, while the tentacles are “translucent white” ( Watson 2008: 186); in contrast, specimens of C. tropica exhibit much intense colors on both the caulus and the hydranth, including its tentacles ( Figs 1 View FIGURE 1 , 2B&D View FIGURE 2 , 3A&B View FIGURE 3 ); only in rare instances, depigmented specimens can be found ( Fig. 2A View FIGURE 2 );

2) the perisarc is not only confined to the proximal part of the caulus, but also to its distal portion {“Perisarc above [transverse red] band thin and becoming almost colourless distally” ( Watson 2008: 185)}; proximally it is reportedly said “thick and gelatinous”, a feature not observed in the present species, in which it is uniformly thin and transparent;

3) the number of tentacles, especially the oral ones, is lower than in C. tropica {“approximately 30 oral tentacles […] arranged in a tuft of two closely set whorls” ( Watson 2008: 185)}; even in polyps with a minimal number of tentacles (e.g., MSNMCoe360: 24 aboral and 28 oral), those surrounding the hypostome are invariably arranged in no less than 4 distinct whorls in C. tropica ;

4) its gonophores are reportedly “fixed sporosacs”, possibly of “cryptomedusoid type […] packed with small ova” ( Watson 2008: 185–186) with a diameter of 10–32 µm;

5) although quite similar, the cnidome composition given by Watson indicates, however, that the various types of nematocysts do not occur at exactly the same locations as in C. tropica [e.g. there are 5 size classes of stenoteles, instead of only 4 in C. tropica ; the desmonemes are absent from the gonophores, while they are present in the medusa of C. tropica ; the capsules identified as “heterotrichous anisorhizas” by Watson likely have a smaller equivalent in C. tropica (15–16 µm vs. ca. 10 µm wide, respectively), and they are said to occur only in the aboral tentacles of the polyp, while they are present in both types of tentacles in C. tropica ];

6) it was found in a temperate area of southern Australia (at the latitude of 38° S), in a habitat characterized by “silty sand heavily bioturbated by infaunal polychaetes and bivalve molluscs”, and a water temperature of 13°C ( Watson 2008: 185), while C. tropica is, according to the present data, a purely tropical species known, for instance, from Indonesia and the Philippines.

Finally , three nominal species have poorly-characterized gonophores, but they can be nevertheless excluded on the following grounds:

1) C. carnea ( Clark, 1877) —as noted by Schuchert (2010: 403–404), the type of gonophores produced by this species is unknown with certainty but, with little doubt, this Alaskan hydroid is very unlikely to occur in tropical waters;

2) C. sagamina Hirohito, 1988 —this species, reportedly yellow in life, with the upper part of the caulus “almost transparent”, has its hydrocauli entirely covered by a perisarc sheath, with no distinct delimitation between the lower, papillary and upper, non-papillary parts ( Hirohito 1988: fig. 2A); its occurrence in temperate waters of Japan (35° N) further supports the distinction with the new species;

3) C. tomoensis Ikeda, 1910 ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 )—although it shares with C. tropica the same development pattern of the perisarc 3, it nevertheless differs through the following features: a) its polyps are proportionally bigger (4–5 cm high, caulus 3–4 mm wide, hydranth 8–10 mm high) ( Ikeda 1910: 153); b) its “ground color is light pink”, and “on the swollen part of the hypostome, on the hydranth-basis, and along the boundary between the nonpapillated upper and the papillated lower regions of the hydrocaulus, a deep pink color with a yellowish tint is prominent. A fine streak of the same color is found on the inner [=adaxial] side of each proximal [=aboral] tentacle” ( Ikeda 1910: 154); c) its hydranths bear more numerous tentacles (38–40 aboral, ca. 70 oral), and the oral whorl is composed of as much as 6–7 verticils ( Ikeda 1910: 154–155); d) each blastostyle gives rise to 10–15 short branches “which all lie on the outer side of [its] stem in two alternate rows” ( Ikeda 1910: 155), while their number does not exceed 7 in C. tropica , and their arrangement is, in contrast, irregular; e) it is known from a temperate part of Japan, between 32– 34° N, and is unlikely to occur between the tropics.

3 “A close examination reveals the fact that the boundary [between the non-papillated and papillated parts of the caulus] corresponds with the lower (sic, =upper) end of perisarc, which is found in the papillated region” ( Ikeda 1910: 158). “The two parts of the hydrocaulus are of a different color and they are also separated from each other by the presence of the perisarc whose development is restricted to the yellow column” ( Okada 1927: 499–500, translated from French).

Distribution. Indonesia: Bali (present study), Ambon ( Vervoort 2009, as C. tomoensis Ikeda, 1910 ; C.G. Di Camillo, pers. comm.); photographic material available online (www.flickr.com) shows specimens in Lombok, Komodo (both in the Lesser Sunda Islands) and Weh (off northern Sumatra). Philippines: Anilao (fully fertile specimens were perfectly identifiable on underwater photographs entrusted to me by several divers), Cebu ( Poppe & Poppe 2022, as Tubularia species). Its known latitudinal range is between 8– 9° S and 13° N, with an evident preference for warm waters.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Corymorpha tropica

| Galea, Horia R. 2023 |

Corymorpha tomoensis

| Vervoort, W. 2009: 760 |

| Ikeda, I. 1910: 153 |