Acroperus neglectus Lilljeborg, 1900

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.189352 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5686932 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/038987B8-AB4D-FF9E-5596-BF04D1EEFF36 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Acroperus neglectus Lilljeborg, 1900 |

| status |

|

Acroperus neglectus Lilljeborg, 1900 View in CoL and A. alonoides Hudendorff, 1876 , two synonyms of A. angustatus ?

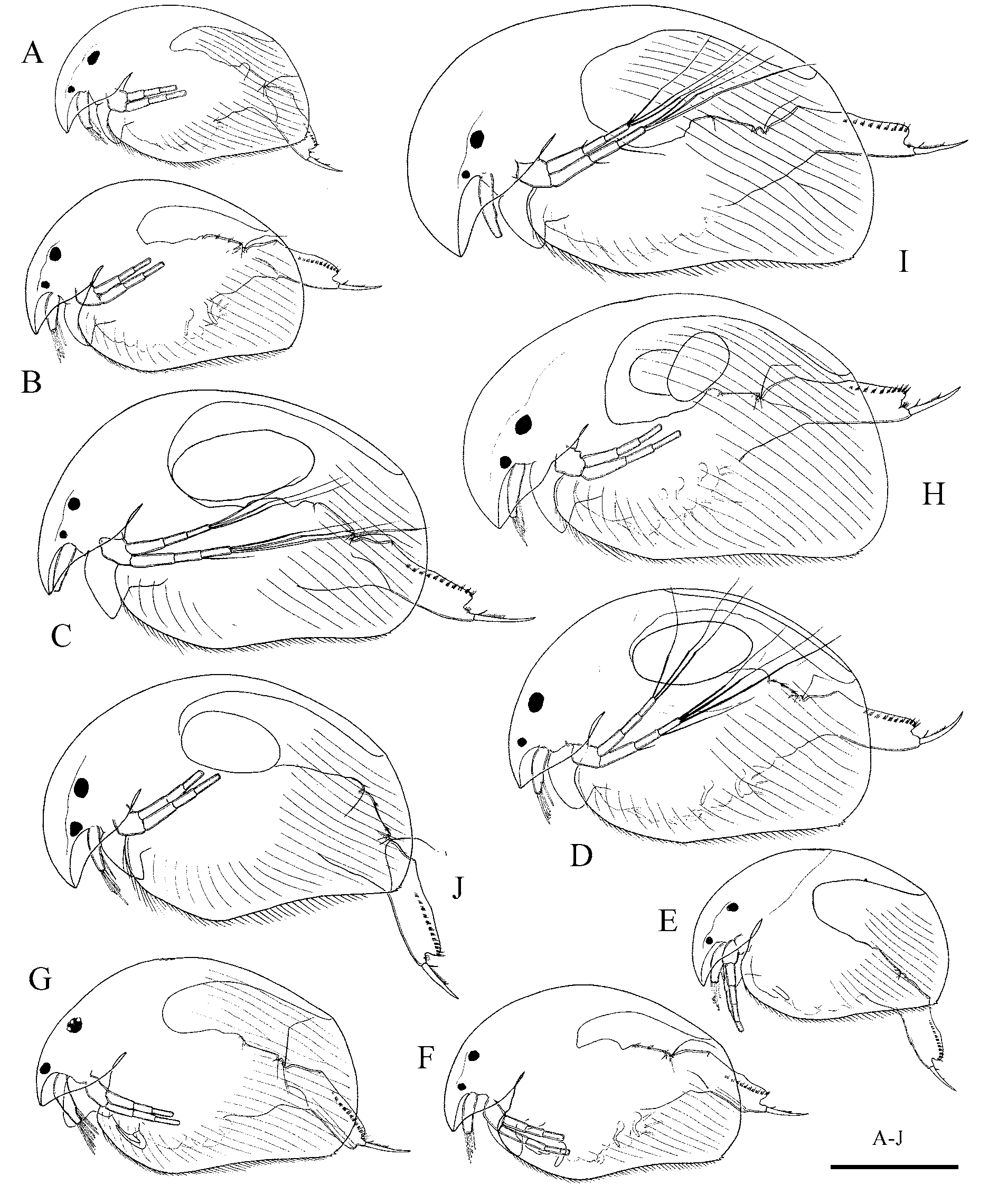

The main diagnostic feature of A. neglectus is a female antennula protruding below the apex of the rostrum, as in an adult male ( Lilljeborg 1900). After the initial description, this species was never recorded again. I personally never encountered living Acroperus females with such antennules. The diagnosis character may be an artefact. During preparation, the cover glass may deform the animal's head through pressure, and antennules are pushed out. Preserved specimens of both A. harpae and A. angustatus may sometimes have this “trait”, but closer study reveals that this is an artefact. Such a specimen was depicted in Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 D: one antennule is in normal position, while other appears to be reaching the end of the rostrum. All these facts suggest that A. neglectus was described from such deformed specimens and is not a valid species. The same can be said about other species with such diagnostic feature—Australian Acroperus sinuatus Henry, 1919 , which also was never reported again after its description ( Smirnov & Timms, 1983). Therefore, I suggest that A. neglectus Lilljeborg is a junior synonym of A. angustatus .

The status of A. alonoides Hudendorff, 1876 is also doubtful. The main diagnostic character of this taxon is a “low” head shield, where the distance between the dorsal head margin and the eye is less than an eye diameter. This character is not reliable, especially with preserved specimens in slides. Shape and size of the eye are quite variable in both studied species of Acroperus (see Figs 1 View FIGURE 1 , 6 View FIGURE 6 ), and during the fixation both eye size and position may change. Specimens with lower keels were revealed in populations of both A. harpae and A. angustatus . The drawing of Hudendorff (1876, pl. 2, fig. 4) is strange, but clearly these specimens have the diagnostic features of A. angustatus —low rectangular body, antennal branches of equal length, and large triangular denticles. The same can be said about A. alonoides populations described by Smirnov (1971) —in my opinion, these specimens ( Smirnov, 1971, fig. 496) are characterized not by the low keel, but, conspicuously large eyes. The diagnostic features of males ( Smirnov 1971, fig. 498) correspond to A. angustatus . On the other hand, Flössner (2000) treats specimens with typical characters of A. harpae , including male postabdomen ( Flössner, 2000, Abb. 126) as A. harpae var. alonoides . In the studied material, I found no additional differences between low-keeled and "normal" populations of both species. It can be concluded that A. alonoides is also a synonym of A. angustatus .

Distribution of A. harpae and A. angustatus . Having revised a geographically large coverage of samples, I think that the data on distribution of both species worldwide should be re-evaluated. A. harpae was reported worldwide, A. angustatus —from Eurasia, North America and Australia ( Smirnov, 1971; Smirnov & Timms, 1983). Few reports include detailed descriptions and/or illustrations and the actual validity of the species cannot be checked. These species are widely distributed in the Palearctic, A. angustatus no less common than A. harpae . The Southern limit of their distribution is unclear. The southernmost occurrence of both may fall in China ( Chiang & Du 1979). The latter descriptions/drawingsare quite accurate (including antennae) and presence here can be confirmed. Both were reported from India by Sharma & Michael (1987), but without data on antennal morphology. Also, both can be expected everywhere in the Mediterranean and Middle Asia. For example, drawings of “ A. harpae ” from Tunisia ( Dumont et al, 1979, p. 264, fig. 5A–E) clearly belong to A. angustatus . Parthenogenetic females of Acroperus from Thailand (Sinev & Sanoamuang, unpubl.) can be identified as A. harpae sensu stricto; A. angustatus is not present in Thailand, and may be does not penetrate so far South.

In North America, Palearctic Cladocera are frequently replaced by the Nearctic siblings. They are recognized only after a detailed study of (limb and male) morphology. An example is the genus Alonopsis Sars, 1862 ( Kubersky, 1977) , which is very close to Acroperus . Therefore, identity of Nearctic populations of Acroperus is uncertain without reliable proof and their taxonomic status remains unclear. Records of A. harpae from the tropics are mostly doubtful, even if short description is provided. Specimens reported from Niger (Dumont et Van de Velde, 1977, p. 89, fig.6G–H) have moderately long antenna with different branch lengths, like A. harpae , but cannot be identified with certainty. Specimens from Chad ( Rey & Saint-Jean, 1968: 97–99, fig. 15 A, 15 D) are more similar in morphology to A. angustatus . Rey & Vasquez (1986) and Hudec (1998) mention animals from Venezuela, similar to A. angustatus in morphology of the antenna, but have somewhat different posteroventral denticles on the valves. The body shape varies from “ harpae -rype” to “ angustatus- type ”. Both A. harpae and A. angustatus were reported from Australia by Smirnov & Timms (1983) but without descriptions.

In conclusion, present taxonomy of Acroperus is incomplete. Future studies are necessary especially clarification of the taxonomic status of American, African and Australian populations.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Genus |

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Genus |