Daubentonia madagascariensis (Gmelin, 1788)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6640345 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6640341 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03877A3E-4F18-5F2F-FF63-F73BF7E7F8FA |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Daubentonia madagascariensis |

| status |

|

Aye-aye

Daubentonia madagascariensis View in CoL

French: Aye-aye / German: Fingertier / Spanish: Aye-aye

Taxonomy. Sciurus madagascariensis Gmelin, 1788 ,

Western Madagascar.

There is a marked difference in size between eastern and north-western representatives ofthis species, with individuals from the eastern part ofthe distribution tending to be larger. Monotypic.

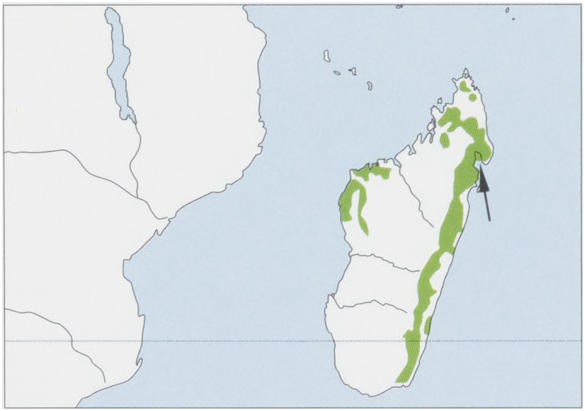

Distribution. Madagascar, mainly in the E, N & CW parts ofthe island, but it evidently occurs in low numbers in pockets across most coastal areas; whether it existed on Nosy Mangabeprior to the mid-1960s introduction remains uncertain. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 30-37 cm, tail 44-53 cm; weight 2.4-2.6 kg (there is a little sexual dimorphism, with females being slightly smaller than males). The Aye-aye is one of the most unusual and distinctive primates. It is immediately recognizable by its large size, prominent ears, long thin fingers and toes, and long bushy tail. Its overall appearance is a dark grayish-brown. The dorsal coat, including that ofthe limbs, consists of a dense layer ofshort, off-white hairs overlaid by a longer, coarser layer of blackish-brown, white-tipped guard hairs, giving the animal a brindled and shaggy appearance. The tail is darkly colored, andits hairs are monochromatic. The ventral coat is similar to the dorsal coat in hair pattern, but it is not as dense and turns whiter on the chest, throat, and face. The head is short, oval-shaped, and large, with a short, tapering, thinly-haired muzzle and prominent eyes that are orientated towardthe front. Thenose is pink andrather pointed. The enormous, highly mobile ears are naked and black. Hands and feet are black with elongated digits, and the third digit of the hand is very slender and withered in appearance.

Habitat. Primary eastern rainforest, deciduous forest and littoral forest, mature and degraded secondary forest, cultivated areas such as plantations (including those producing sugar cane, coconuts, and cloves), mangrove swamps, and dry scrub forest. The elevational range ofthe Aye-aye is from near sea level up to 1875 m.

Food and Feeding. Diet of the Aye-aye varies by locality and season. It consists mainly ofinsects and their wood-boring larvae, along with hard-shelled fruits, seeds, tree sap, bamboo shoots and pith, flowers, nuts, nectar, honey (obtained by the destruction of active hives), fungus, and eggs. Presence ofthe Aye-aye in some areas appears to be determined by one ofits primary food sources, seeds of “ramy” ( Canarium madagascariense, Burseraceae ). Other dietary staples include seeds of Orania trispatha ( Arecaceae ) and Terminalia catappa ( Combretaceae ); beetle and moth larvae embedded in trees, bamboo, and seeds of Terminalia fruit; cankerous growths on Intsia bijuga ( Fabaceae ); nectar from traveler's palm ( Ravenala madagascariensis , Strelitziaceae ); and crops such as coconuts, lychees, sugar cane, and mangos. Crop damage by Aye-ayes can be considerable; in one case, they destroyed 80-100% ofthe coconut crop in two villages. Aye-ayes spend most oftheir active hours foraging for insect larvae. Using their oversized, highly sensitive ears, they intently listen for sounds oftheir quarry tunneling within the wood and simultaneously tap the surface of the bark with their fingers to trace hollow pathways. When a grub is located, the Aye-aye usesits long front teeth to gouge a hole in the wood and then extracts the grub with its wiry middle finger. The same basic technique is used to get at the insides of coconuts and eggs and even while drinking, using the finger to draw water to the mouth. This movement of the third finger from the food or water to the mouth can be extraordinarily rapid; it has been measured at a rate of3-3 strokes/second. They are extremely noisy eaters. Captive individuals have been known to hide coconuts.

Breeding. The Aye-aye breeds throughout the year. Females have a regular monthly cycle, which lasts, on average, 47 days in captivity. They have an externally visible genital swelling, and the vulva changes color in estrus. Full estrus lasts 3-9 days. In the wild, swollen genitalia and an increase in scent marking have been observed in both sexes before and during mating activity. The solicitation posture of a captive female consists ofplacing herselfsideways next to a male and then turning her head toward him. Other methods offemale solicitation include vocalizations and running up to the male, touching faces, and then running away. Females are polyandrous; they mate with more than one male during a single estrus. As many as six males will group around a female and aggressively interact for access to her. Although copulation is quick in captivity (generally lasting about two minutes), it lasts for about one hour in the wild—possibly a consequence of mate-guarding by a male to prevent access by other males. Males attempt to disrupt copulation to mate with her themselves. They copulate suspended from a branch, with the female holding on to the branch and the male grasping only the female. After copulating, the pair may groom each other, or the female may move away quickly and resume calling. The reproductive rate of Aye-ayes is low, a single young born about every 2-3 years. Births may take place at any time of the year, but they usually occur in February or March after a gestation of 164-172 days. The newborn spends the first couple of months at or near the nest. The mother carries it in her mouth and will often “park”it in a nest while she forages. Infants have green eyes for the first nine weeks, after which they become brown. Ears are floppy for the first six months or so, and the fur on the face, shoulders, and belly is paler than that of adults. They begin to eat solid foods at about three months of age. Play is very important for the young. Full independence appears to occur when they are 18 months to two years old. Females typically begin to reproduce at about 3-5 years old, and males will start copulating (though not successfully) at 2-5 years old. Age of dispersal is unknown. Individuals have lived up to 24 years in captivity.

Activity patterns. Nocturnal and mainly arboreal. Aye-ayes sleep generally rolled up into a ball with the tail wrapped over the body, during the day in tree forks, vine tangles, or their large bowl-shaped nests. They emerge from the nest as early as 30 minutes before sunset and may not return to until after sunrise. Males become active earlier than females. Over the course of the night, more than 50% of an Aye-aye’s timeis spent moving, interspersed with bouts of feeding, grooming, and resting. When they rest, they remain sedentary but are fully aware of their surroundings and not asleep. These rest periods can last for as long as two hours. Individuals groom themselves several times during the night in bouts lasting up to 30 minutes—the longer the session, the higher in the canopy they perch, presumably for safety. The long, narrow third finger is used for combing, scratching, and cleaning the fur; the other fingers are flexed during these behaviors.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Aye-ayes are largely solitary, but they have complex social interactions that include foraging in tandem and social groupings such as several males or male-female dyads. Males occupy much larger home ranges (125-215 ha) than females (30-40 ha). Social grooming can involve both sexes. In captivity, males groom females far more than females groom males. Male—female and male—male territories overlap; those of the females do not. Indeed, females rarely interact at all, and when they do, encounters are aggressive. The Aye-aye has a multimale—multifemale mating system.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Near Threatened on The IUCN Red List. However, at the JUCN/SSC Lemur Red-Listing Workshop held in July 2012, the Aye-aye was assessed as endangered due to an inferred and projected ongoing and future population decline of more than 50% over three generations. The Ayeaye is still killed in some areas as a harbinger of evil and a crop pest (e.g. coconuts), and they are hunted for food. Habitat destruction also threatens them throughout their range, with trees such as Intsia bijuga and Canarium madagascariense—dietary staples—preferentially harvested for construction of boats, houses, and coffins. Aye-ayes are known to occur in twelve national parks (Andohahela, Andringitra, Mananara-Nord, Mantadia, Marojejy, Masoala, Midongy du Sud, Montagne d’Ambre, Ranomafana, Sahamalaza-Iles Radama, Tsingy de Bemaraha, and Tsingy de Namoroka), three strict nature reserves (Betampona, Tsaratanana, and Zahamena), and 13 special reserves (Ambatovaky, Analamazaotra, Analamerana, Anjanaharibe-Sud, Ankarana, Bora, Foret d’Ambre, Kalambatritra, Manombo, Manongarivo, Marotandrano, Nosy Mangabe, and Pic d’Ivohibe). Theyalso are found in the forests of Daraina (part of the Loky-Manambato protected area) and Maroala and Anjiamangirana classified forests. Despite occurring in many protected areas, their presence is often based only on signs and infrequent sightings, and little is known about their population sizes and dynamics. There is an urgent need for a systematic census of this important flagship species throughout its range, with the ultimate goal of developing a conservation action plan. In the mid-1990s, the total world population was estimated at 1000-10,000.

Bibliography. Albignac (1987), Ancrenaz et al. (1994), Andriamasimanana (1994), Ankel-Simons (1996, 2000), Barrows (2001), Beattie et al. (1992), Bomford (1976, 1981), Bradt (1994, 2007), Britt et al. (1999), Buettner-Janusch & Tattersall (1985), Carroll & Beattie (1993), Carroll & Haring (1994), Cartmill (1974), Cohn (1993), Constable et al. (1985), Curtis (1992), Curtis & Feistner (1994), Del Pero et al. (2005), Dubois & lzard (1990), Duckworth (1993), Duckworth et al. (1995), Dutrillaux & Rumpler (1995), Erickson (1994, 1995a, 1995b, 1998), Erickson et al. (1998), Feistner & Ashbourne (1994), Feistner & Carroll (1993), Feistner & Sterling (1995), Feistner & Taylor (1998), Feistner et al. (1994), Fleagle (1988), Ganzhorn & Rabesoa (1986a, 1986b), Glander (1994a, 1994b), Godfrey & Jungers (2003), Godfrey et al. (2003a), Goix (1993), Goodman & Ganzhorn (2004), Groves (1974, 1989, 2001), Grzimek (1968), Hakeem et al. (1996), Harcourt & Thornback (1990), Haring et al. (1994), Hawkins et al. (1990), Iwano (1991a, 1991b), Iwano & Iwakawa (1988, 1991), Iwano et al. (1991), Jolly (1998), Jones (1986), Jungers et al. (2002), Jury (2003), Kappeler (1997), Koenig (2005), Krakauer et al. (2001, 2002), MacPhee & Raholimavo (1988), Milliken et al. (1991), Mittermeier, Konstant et al. (1992), Mittermeier, Louis et al. (2010), Napier & Napier (1967), Nicoll & Langrand (1989), O'Connor et al. (1986), Oxnard (1981), Petter (1977), Petter & Charles-Dominique (1979), Petter & Petter (1967), Petter & Peyrieras (1970b), Petter-Rousseaux & Bourliere (1965), Pollock et al. (1985), Poorman-Allen & lzard (1990), Price & Feistner (1994), Quinn & Wilson (2004), Rahajanirina & Dollar (2004), Rakotoarison (1995b), Randriananbinina et al. (2003), Randrianarisoa et al. (1999), Rendall (1993), Roos (2003), Roos et al. (2004), Rowe (1996), Rumpler, Warter, Ishak & Dutrillaux (1989), Rumpler, Warter, Petter et al. (1988), Schmid & Smolker (1998), Schwartz & Tattersall (1985), Schwitzer & Lork (2004), Simons (1993, 1994), Simons & Meyers (2001), Soligo (2005), Soligo & Miller (1999), Stanger & Macedonia (1994), Stephan (1972), Sterling (1992, 1993a, 1993b, 1994a, 1994b, 1994c, 1998, 2003), Sterling & McFadden (2000), Sterling & McCreless (2006), Sterling & Povinelli (1999), Sterling & Rakotoarison (1998), Sterling & Ramaroson (1996), Sterling & Richard (1995), Sterling et al. (1994), Sussman (1977), Sussman et al. (1985), Tattersall (1982), Tattersall & Schwartz (1974), Thalmann et al. (1999), Walker (1975), Winn (1989, 1994a, 1994b), Yoder (1997), Yoder et al. (1996).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Daubentonia madagascariensis

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Sciurus madagascariensis

| Gmelin 1788 |