Odontomachus Latreille

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3817.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A3C10B34-7698-4C4D-94E5-DCF70B475603 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5117500 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03775906-A60E-2C57-FF17-FBFA13E7FDC7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Odontomachus Latreille |

| status |

|

Odontomachus Latreille View in CoL View at ENA

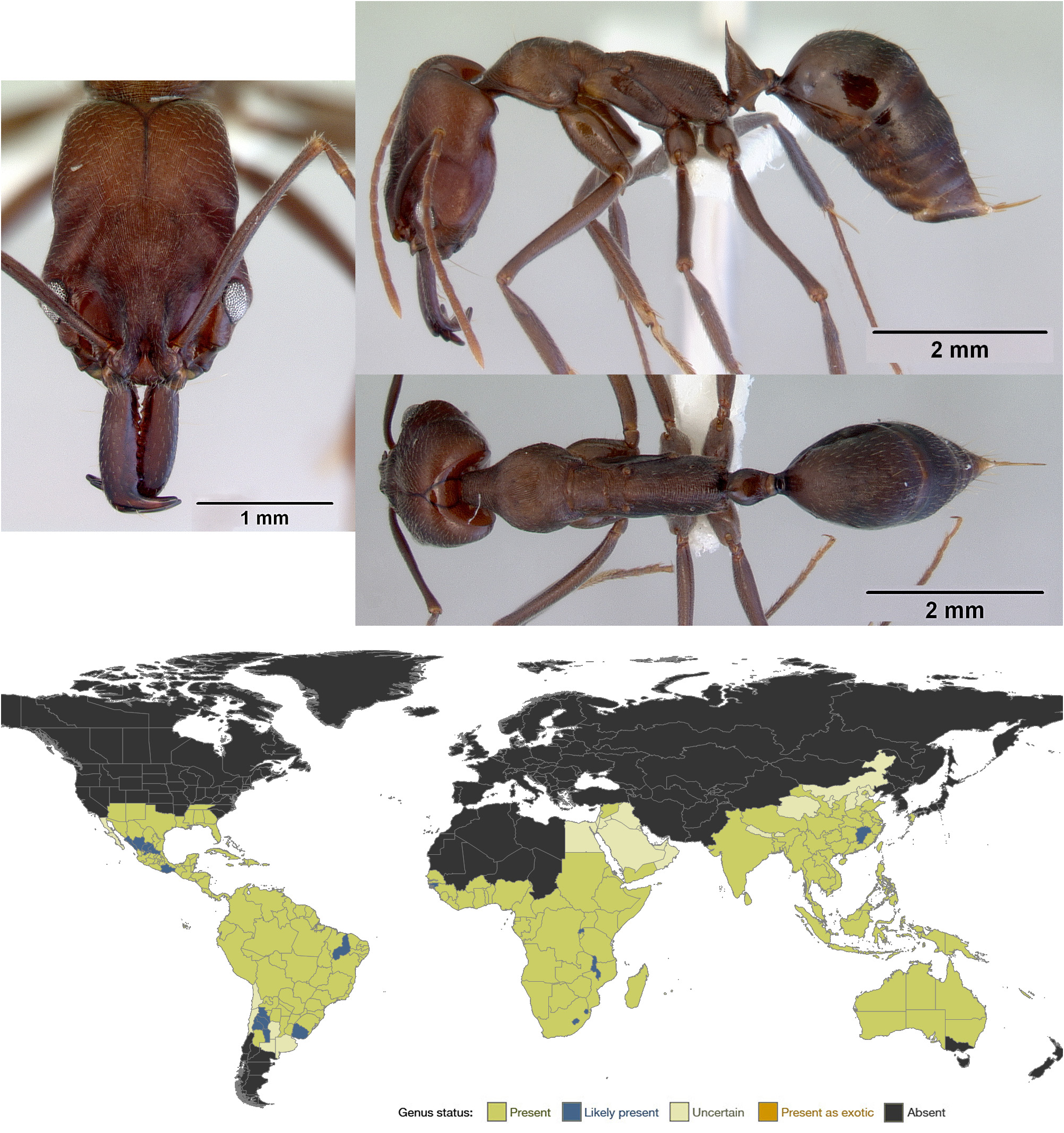

Fig. 19 View FIGURE 19

Odontomachus Latreille, 1804: 179 View in CoL (as genus). Type-species: Formica haematoda Linnaeus, 1758: 582 ; by monotypy.

Pedetes Bernstein, 1861: 7 . Type-species: Pedetes macrorhynchus Bernstein, 1861: 8 ; by monotypy. Dalla Torre, 1893: 51 ( Pedetes as junior synonym of Odontomachus View in CoL ).

Champsomyrmex Emery, 1892: 558 . Type-species: Odontomachus coquereli Roger, 1861: 30 View in CoL ; by monotypy. Brown, 1976: 96 ( Champsomyrmex as junior synonym of Odontomachus View in CoL ).

Thempsomyrmex Forel, 1893a: 163 (incorrect subsequent spelling of Champsomyrmex ).

Myrtoteras Matsumura, 1912: 191 . Type-species: Myrtoteras kuroiwae Matsumura, 1912: 192 (junior synonym of Odontomachus monticola Emery, 1892 View in CoL ). Brown, 1976: 96 ( Myrtoteras as junior synonym of Odontomachus View in CoL ).

Odontomachus View in CoL is a large genus (63 described extant species) widespread and abundant in the tropics and subtropics of the world, with a few species extending into temperate regions. Like its sister genus Anochetus View in CoL , Odontomachus View in CoL is notable for its remarkable trap mandibles. The closure of Odontomachus View in CoL mandibles is the fastest movement ever recorded in any animal.

Diagnosis. Workers of Odontomachus are so distinctive that they are difficult to confuse with those of any other genus except Anochetus , the sister genus of Odontomachus . The unusual trap mandibles and head shape of Odontomachus are synapomorphic with Anochetus , but the genera are readily differentiated by examination of the posterior face of the head. In Odontomachus the nuchal carina is V-shaped medially, and the posterior surface of the head has a pair of dark converging apophyseal lines. In Anochetus the nuchal carina is continuously curved and the posterior surface of the head lacks visible apophyseal lines. These genera also tend to differ in size ( Anochetus are generally smaller, though there is some overlap), propodeal teeth (absent in Odontomachus but usually present in Anochetus ), and petiole shape (always coniform in Odontomachus , but variable in Anochetus ).

Synoptic description. Worker. Medium to large (TL 6–20 mm; Brown, 1976) slender ants with the standard characters of Ponerini . Mandibles straight and narrow, articulating with the head medially, capable of being held open at 180°, and with a trio of large apical teeth and often a row of smaller teeth along the masticatory margin. Head with a pair of long trigger setae below the mandibles. Clypeus truncate laterally and anteriorly. Frontal lobes small and relatively widely spaced. Head strangely shaped: much longer than wide, with a distinct constriction behind the eyes and then often a gradual broadening posteriorly, the posterior margin of the head straight or mildly concave, the nuchal carina V-shaped medially, the posterior surface of the head with a pair of dark converging apophyseal lines. Eyes fairly large, located anterior of head midline on temporal prominences. Metanotal groove shallowly to deeply impressed. Propodeum broadly rounded dorsally, as broad as mesonotum but narrower than pronotum. Propodeal spiracles small, circular to ovoid. Metatibial spur formula (1s, 1p). Petiole surmounted by a conical node, topped by a posteriorly-directed spine of variable length. Gaster without a girdling constriction between pre- and postsclerites of A4. Stridulitrum almost always present on pretergite of A4. Head and body shiny to lightly striate, with very sparse pilosity and pubescence. Color variable, orange to black.

Queen. Similar to worker but slightly larger, alate and with the other caste differences typical for ponerines ( Brown, 1976). Queens of O. coquereli are ergatoid ( Molet et al., 2007).

Male. See descriptions in Brown (1976) and Yoshimura & Fisher (2007).

Larva. Larvae of various Odontomachus species have been described by Wheeler (1918), Wheeler & Wheeler (1952, 1964, 1971a, 1980), Brown (1976), and Petralia & Vinson (1980).

Geographic distribution. Odontomachus is abundant in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world, though it is most diverse in the Asian tropics and the Neotropics. Australia boasts a handful of species, while Africa has two species ( O. assiniensis and O. troglodytes ) and the Malagasy region has three species ( O. coquereli , O. troglodytes , and O. simillimus , the latter apparently introduced to the Seychelles; Fisher & Smith, 2008). A few species extend into temperate regions, notably in the southwestern United States, northeastern China, central Argentina, and southwestern Australia (reviewed in Brown, 1976).

Ecology and behavior. In most respects Odontomachus are fairly typical ponerines. The nesting habits of many species have been observed, and most of these nest in soil or rotting wood (e.g., O. affinis: Brandão, 1983 ; O. bauri: Ehmer & Hölldobler, 1995 ; O. brunneus , O. clarus , O. relictus , and O. ruginodis: Deyrup & Cover, 2004 ; O. cephalotes: Wilson, 1959b ; O. chelifer: Fowler, 1980 ; Passos & Oliveira, 2004; O. coquereli: Molet et al., 2007 ; O. erythrocephalus: Longino, 2013 ; O. opaciventris: de la Mora et al., 2007 ; O. rixosus: Ito et al., 1996 ; O. simillimus: Wilson, 1959b ; van Walsum et al., 1998; O. tyrannicus: Wilson, 1959b ), though some species will nest in more unusual locations such as in abandoned termite nests (Déjean et al., 1996, 1997) or arboreally (e.g., O. troglodytes: Colombel, 1972 ; O. brunneus , O. hastatus , and O. mayi ; Brown, 1976; O. bauri and O. hastatus: Longino, 2013 ). The nests of O. bauri are apparently polydomous ( Ehmer & Hölldobler, 1995). Odontomachus workers are monomorphic and are epigeic foragers, and some species are at least partially arboreal in their habits ( Brown, 1976; Longino, 2013). Most species are generalist predators of arthopods, though many species partially specialize on certain types of prey, especially termites (e.g., Fowler, 1980; Lévieux, 1982; Ehmer & Hölldobler, 1995). At least some species will also tend honeydew-secreting insects or visit extrafloral nectaries (e.g., O. affinis: Borgmeier, 1920 ; O. bauri , O. hastatus , and O. panamensis: Schemske, 1982 ; Longino, 2013; O. troglodytes: Evans & Leston, 1971 ; Lachaud & Déjean, 1991a), and the Neotropical species O. chelifer is known to eat fruit and the arils of certain seeds, which the ants ultimately disperse ( Pizo & Oliveira, 1998; Passos & Oliveira, 2002, 2004). O. laticeps and O. meinerti (as O. minutus ) also collect seeds with nutritious arils ( Horvitz & Beattie, 1980; Horvitz, 1981). O. malignus is notable for its habit of foraging among corals at low tide ( Wilson, 1959b). Foraging workers of O. bauri navigate using visual cues from the forest canopy overhead as well as chemical cues ( Oliveira & Hölldobler, 1989). Recruitment of nestmates via tandem running was observed in O. troglodytes ( Lachaud & Déjean, 1991a) .

Colony size is highly variable across the genus, ranging from an average of only 18 workers in O. coquereli ( Molet et al., 2007) to as many as 10,000 workers in O. opaciventris (de la Mora et al., 2007) . Most species seem to have colony sizes of several hundred workers: O. chelifer colonies average between 100 to 650 workers ( Fowler, 1980; Passos & Oliveira, 2004), colonies of O. rixosus had an average of 142 workers ( Ito et al., 1996), and O. bauri is reported to have up to 300 workers per colony ( Jaffe & Marcuse, 1983), though O. troglodytes colonies can have over 1,000 workers ( Colombel, 1970a).

Most species of Odontomachus have typical winged queens and semi-claustral nest founding ( Brown, 1976), though O. coquereli has wingless ergatoid queens and colonies apparently reproduce by division ( Molet et al., 2007). An undescribed species from Malaysia is also reported to have ergatoid queens ( Gobin et al., 2006), and colony reproduction by fission is suspected to occur in some other species ( Brown, 1976). While some Odontomachus species are likely to be monogynous, many species are polygynous (e.g., O. assiniensis: Ledoux, 1952 ; O. cephalotes: Peeters, 1987 ; O. chelifer: Medeiros et al., 1992 ; O. rixosus: Ito et al., 1996 ; O. troglodytes: Ledoux, 1952 ). Queens of O. rixosus perform many of the tasks more typical of the worker caste, including foraging outside the nest ( Ito et al., 1996). In the most detailed series of studies on a single Odontomachus species , Colombel examined various aspects of the behavior of O. troglodytes , including caste determination ( Colombel, 1978), egg development ( Colombel, 1974) reproduction by workers ( Colombel, 1972), ecology, nest structure, demographics and population dynamics ( Colombel, 1970a), egg-laying by queens ( Colombel, 1970b), and alarm pheromones ( Colombel, 1968). The laying of haploid eggs by workers has also been observed in O. chelifer ( Medeiros et al., 1992) , O. rixosus ( Ito et al., 1996) , and O. simillimus ( van Walsum et al., 1998) . Wheeler et al. (1999) examined the egg proteins of O. chelifer and O. clarus .

Only a handful of papers have been published on the social behavior of Odontomachus . Polyethism in O. troglodytes was studied by Déjean & Lachaud (1991), while division of labor in O. affinis was examined by Brandão (1983). Powell & Tschinkel (1999) discovered that the workers of O. brunneus organize themselves into a social hierarchy via ritualized dominance interactions, with repercussions for task specialization within the nest. Whether similar heirarchies exist among workers in other Odontomachus species is unknown, though dominance heirarchies exist among queens in colonies of the polygynous species O. chelifer ( Medeiros et al., 1992) . Jaffe & Marcuse (1983) observed both nestmate recognition and territorial aggression in O. bauri . Aspects of the mating behavior of O. assiniensis , the other African Odontomachus species , were studied by Ledoux (1952).

Wheeler & Blum (1973) identified the mandibular glands as the source of alarm pheromones in O. brunneus , O. clarus and O. hastatus . Morgan et al. (1999) examined the mandibular gland secretions of O. bauri , while Longhurst et al. (1978) studied the mandibular gland secretions of O. troglodytes and the response of males to these secretions. Oliveira & Hölldobler (1989) identified the roles of pygidial, mandibular and poison gland secretions in O. bauri for recruitment, alarm and attack behaviors. Alarmed Odontomachus workers can also stridulate (e.g. Carlin & Gladstein, 1989).

The trap mandibles and associated behaviors of Odontomachus (and Anochetus ) rank among the most specialized of any ponerine. When hunting, Odontomachus workers hold their highly modified mandibles open at 180° and shut them with extreme force and speed on their prey. In fact, this is the fastest movement ever measured in any animal ( Patek et al., 2006; Spagna et al., 2008). The contact of trigger setae (located beneath the mandibles) with the prey triggers the mandibular closure. The morphological, physiological and neurological characteristics of trap mandibles (and associated structures and behaviors) have been extensively studied (e.g., Gronenberg et al., 1993; Gronenberg & Tautz, 1994; Gronenberg, 1995a, 1995b; Ehmer & Gronenberg, 1997; Just & Gronenberg, 1999; Paul & Gronenberg, 1999; Spagna et al., 2008). Kinematic data indicate that the force of jaw closure in Odontomachus scales positively with body size, while acceleration scales inversely with body size ( Spagna et al., 2008). The significance of these scaling relationships for the optimal foraging strategy in a given species is unknown.

The sequence of actions taken during prey capture by a hunting Odontomachus worker was summarized by de la Mora et al. (2007). Upon detection of a suitable prey item, the worker antennates it, then withdraws the antennae and snaps its mandibles shut on the prey. Generally the prey are held in the mandibles, lifted off the substrate, stung, and then transported back to the nest, though sometimes stinging is not necessary ( Brown, 1976). The exact behavioral sequence used during prey capture varies somewhat depending on the Odontomachus species and the identity of the prey. For example, multiple mandibular strikes may be used to stun or dismember the prey. Odontomachus workers are often cautious during prey capture, especially with potentially dangerous prey such as termites. De la Mora et al. (2007) describe the predatory behavior of O. opaciventris in detail; the foraging behaviors of several other Odontomachus species have been described by other authors (e.g., O. assiniensis: Ledoux, 1952 ; O. bauri: Jaffe & Marcuse, 1983 ; O. chelifer: Fowler, 1980 ; O. troglodytes: Déjean, 1982 ?, 1987; Déjean & Bashingwa, 1985). Déjean (1987) found that workers of O. troglodytes learn to avoid noxious prey.

Rapid mandibular strikes are used by Odontomachus to perform a variety of specialized tasks in addition to prey capture. Patek et al. (2006) found that workers of O. bauri utilize the force of their mandible strikes to bounce to safety (or to bounce onto intruders), and also to eject intruders away. This latter behavior (the “bouncer defense”) was studied in detail in O. ruginodis by Carlin & Gladstein (1989). In addition to these highly specialized tasks, the mandibles of Odontomachus remain functional for more typical activities such as nest construction and brood care ( Just & Gronenberg, 1999).

Phylogenetic and taxonomic considerations. Odontomachus was erected by Latreille (1804) to house the single species Formica haematoda Linnaeus , and it has experienced relative taxonomic stability at the genus level since then, except for the recognition of several junior synonyms: Pedetes ( Bernstein, 1861) , Champsomyrmex ( Emery, 1892) , and Myrtoteras ( Matsumura, 1912) . Odontomachus has had a somewhat more unsettled taxonomic history at the tribe and family level. Initially placed in Ponerites ( Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1835), then Poneridae ( Smith, 1857), Odontomachus (and its sister genus Anochetus ) spent most of the latter half of the 19 th century and most of the 20 th century in a state of flux, variously placed in its own family Odontomachidae (e.g., Smith, 1871), in a separate subfamily within Formicidae ( Odontomachidae or Odontomachinae ; e.g., Mayr, 1862), in tribe Odontomachini of Ponerinae (e.g., Forel, 1893a; sometimes also spelled Odontomachii, as in Forel, 1893a), in Ponerini subtribe Odontomachiti ( Brown, 1976) , or simply in Ponerini (e.g., Emery & Forel, 1879, and most recent authors). This taxonomic chaos was the result of the highly derived mandible and head structure of Odontomachus , which led many authors to believe that it was unrelated to the more typical genera in Ponerinae .

Schmidt's (2013) molecular phylogeny of the Ponerinae confirms that Odontomachus is a member of tribe Ponerini , and that its sister is Anochetus , a result supported unequivocally by morphological synapomorphies of their head and mandibles (among other characters). The phylogeny is equivocal about the monophyly of Odontomachus ( O. coquereli is resolved as either sister to the other Odontomachus species or as sister to Anochetus , with approximately equal probability), and it is possible that Odontomachus and Anochetus will prove to not be mutually monophyletic (as suggested by Brown, 1976). On the other hand, a species level phylogeny for these genera, which includes additional taxa and genes, strongly supports their reciprocal monophyly, though some phylogenetically critical Anochetus taxa were not sampled (C. Schmidt, unpublished data). This is consistent with the findings of Santos et al. (2010), who examined the chromosomes of both genera. We are therefore retaining Anochetus and Odontomachus as distinct genera. Additional taxon sampling may reveal that one or the other of these genera is non-monophyletic, in which case Anochetus would likely be synonymized under Odontomachus . The sister group of Odontomachus + Anochetus is still unresolved.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Odontomachus Latreille

| Schmidt, C. A. & Shattuck, S. O. 2014 |

Myrtoteras

| Brown, W. L. Jr. 1976: 96 |

| Matsumura, S. 1912: 191 |

| Matsumura, S. 1912: 192 |

Champsomyrmex

| Brown, W. L. Jr. 1976: 96 |

| Emery, C. 1892: 558 |

| Roger, J. 1861: 30 |

Pedetes

| Dalla Torre, K. W. von 1893: 51 |

| Bernstein, A. 1861: 7 |

| Bernstein, A. 1861: 8 |

Odontomachus

| Latreille, P. A. 1804: 179 |

| Linnaeus, C. 1758: 582 |